BDS and the Oscars: How Screenwriter Ben Hecht Defied an Anti-Israel Boycott

Hollywood has a model of a principled political stand in the writer of ‘Gone With the Wind’ and the Broadway hit ‘The Front Page’

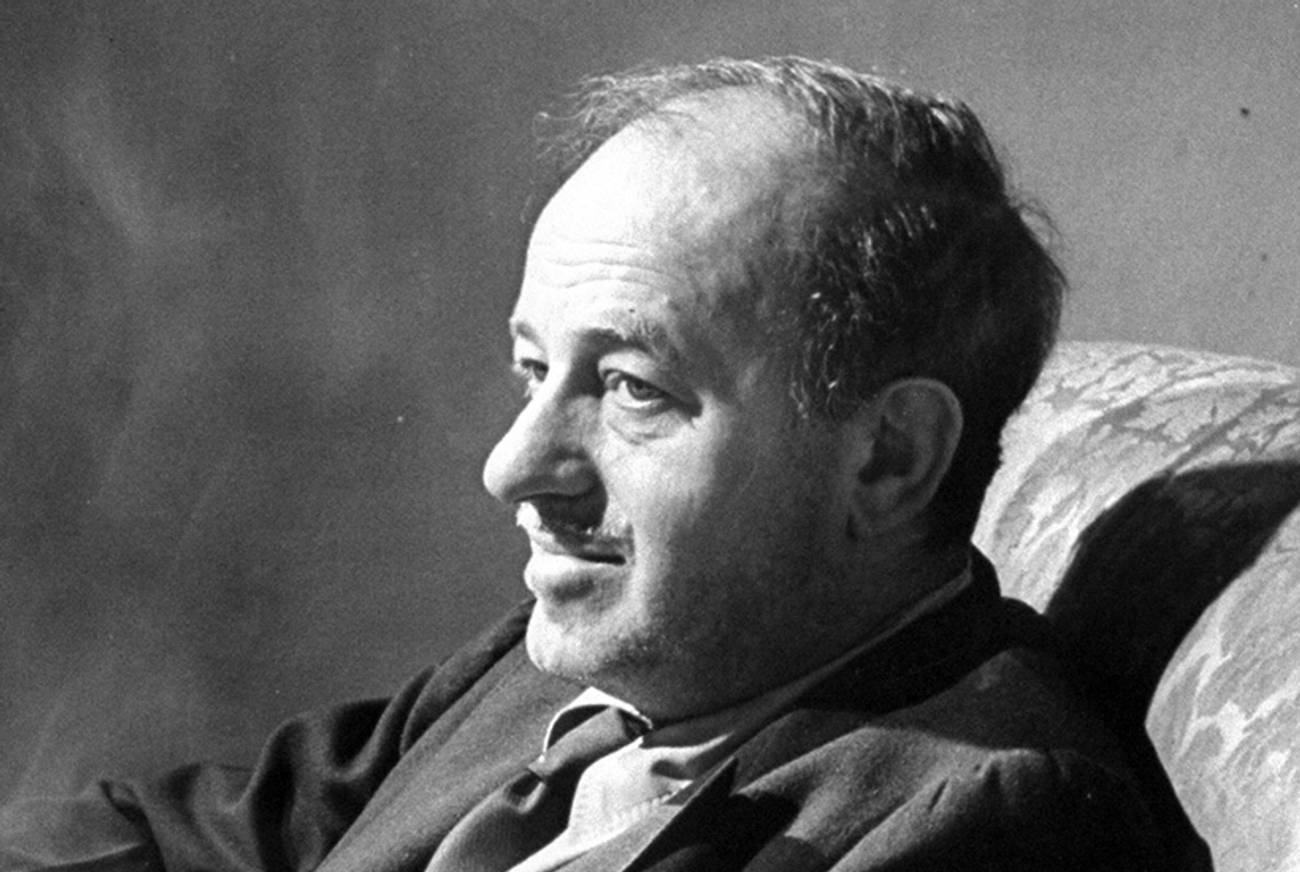

Hollywood screenwriter Ben Hecht said he “beamed with pride” when he heard the news on that autumn afternoon in 1948: The British had declared a boycott against him. By day, Hecht was the highest-paid screenwriter in Hollywood, but by night his typewriter had been cranking out fiery newspaper ads denouncing England’s Palestine policy. Now he was going to pay a price for his unbridled opinions.

Feb. 28 will mark 120 years since Hecht’s birth, an auspicious anniversary, perhaps, to consider his response to a dilemma that friends of Israel now face daily: how to respond to an anti-Israel boycott. The son of Russian Jewish immigrants, Hecht grew up in Racine, Wisc., and Chicago in what he described as a “large, extended, nutty Jewish family of wild uncles and half-mad aunts.” One of his most vivid childhood memories was of his Aunt Chasha taking him to a play in which a policeman wrongly accused another character of theft. The excitable young Ben shouted in protest from the audience, prompting the theater manager to demand an apology for the child’s disruptive behavior. Chasha responded by hitting the manager over the head with her umbrella. “Remember what I tell you,” she explained to her nephew. “That’s the way to apologize.”

That attitude seems to have guided Hecht as he blazed his way through every challenge or cause he took on. His first novel landed him in court on obscenity charges; Clarence Darrow served as his defense attorney. (Hecht lost the case but won national notoriety.) Just five years later, he won the very first Academy Award for original screenplay, for Underworld; the irreverent Hecht boasted that he used the Oscar statuette as a doorstop. A year after that, his play about the newspaper business, The Front Page, was a smash hit on Broadway.

Surveying a career that included 65 film scripts (including Gone With the Wind), 25 books, 20 plays, and hundreds of short stories and magazine articles, film critic Judith Crist dubbed Hecht “the most prolific multimedia child of this century.” But nothing could compare to the controversy Hecht ignited when he stood up for the right of the Jewish people to build a modern state in their ancestral homeland.

***

Earlier in his life, Hecht had shown little interest in anything Jewish. His first marriage (in 1915) was to a non-Jew, and one of his early novels portrayed American Jews in such unflattering terms that a group of rabbis in Cleveland declared they would not allow him to be buried in their city (“an honor nobody I know has ever yearned for,” his second wife, Rose, once quipped).

Hitler changed all that. “The German mass murder of the Jews … brought my Jewishness to the surface,” Hecht later recalled. In 1941 he joined the Fight for Freedom Committee, which urged a pre-emptive military strike against Nazi Germany. After the United States entered the war, he forged a fateful alliance with the maverick Jewish activists known as the Bergson Group. Employing tactics that are commonplace today but seemed shocking back then, the Bergsonites used rallies, newspaper ads, and Capitol Hill lobbying to plead for the rescue of Jewish refugees from the Nazis. Hecht authored the most memorable of those newspaper ads, with headlines such as “Time Races Death—What Are We Waiting For?” and “Help Prevent 4,000,000 People from Becoming Ghosts.”

Yitshaq Ben-Ami, one of the leaders of the group, later wrote that the rescue campaign “would not have gained the scope and intensity it did if not for Hecht’s gifted pen—he had a compassionate heart, covered up by a short temper, a brutal frankness, and an acid tongue.”

After the war, Hecht and the Bergson Group turned their focus to the struggle for Jewish statehood in Palestine. In 1946, Hecht drew national attention to the Zionist cause with his controversial Broadway play A Flag Is Born (starring 22-year-old Marlon Brando), which The London Evening Standard judged “the most virulent anti-British play ever staged in the United States.” Hecht’s purpose was to drum up American support for the revolt being waged in Palestine by Jewish underground militias such as the Irgun Zvai Leumi and (at times) the Haganah. Much to the dismay of British officialdom, Flag openly compared the Jewish revolt to colonial America’s own rebellion against England. (The Bergson Group’s publicity for the play compared Hecht himself to Tom Paine.)

Hecht’s newspaper ads cheering the Jewish militants, with headlines like “This Way to Freedom!” and “Attack Is the Best Defense! Irgun is the Best Attack!” infuriated the British government and public alike. The most brazen of the ads was called “Letter to the Terrorists of Palestine.” Hecht did not, of course, agree that the Jewish fighters were terrorists; that was the term applied to them by the British and their other critics. But it was typical Hecht to take an insult and throw it back in the accuser’s face.

The central claim of Hecht’s open letter, which was published in May 1947, was that most grassroots American Jews were cheering for the rebels. Two-thousand years of homelessness and persecution, topped off by England’s betrayal and harsh treatment of Palestine Jewry, had driven them to desperation, Hecht argued: “Every time you blow up a British arsenal [in Palestine], or wreck a British jail, or send a British railroad train sky high, or rob a British bank or let go with your guns and bombs at the British betrayers and invaders of your homeland, the Jews of America make a little holiday in their hearts.”

Outraged British Embassy officials in Washington sought—unsuccessfully—to convince the Truman Administration to deport Peter Bergson (he was not a U.S. citizen), revoke the Bergson Group’s tax-exempt status, or at least prohibit government employees from publicly endorsing the group. But Hecht had his defenders, too: the popular syndicated columnist Walter Winchell, for one, defended Hecht’s ads for exposing the British, who, he wrote, had become “the Brutish” by harshly suppressing “Palestinian patriots” who were no different from “our Minute Men.” British newspapers denounced Hecht and Winchell as “a couple of damned fools.”

Hecht’s line about “making a holiday in their hearts” must have struck an especially raw nerve among the British public, because it was prominently cited, a year and a half later, when England’s Cinematograph Exhibitors Association—the distributor of films to British movie theaters—announced a ban on all movies in which Hecht had a hand. The timing of the ban is noteworthy: By October 1948, the Jewish revolt had ended, the British had long since withdrawn from Palestine, and the State of Israel had been proclaimed. So, the ban was not an attempt to influence either Hecht or any government policy decisions. It appears to have been motivated by nothing more complicated than hurt feelings and wounded pride. The British had lost. And now they were taking it out on Ben Hecht.

With typical swagger, Hecht wrote that he “perked up” when he heard the news. “I beamed on it as the best press notice I had ever received. … An empire hitting at a single man and passing sanctions against him! There was something to swell a writer’s bosom and add a notch to his hat size. I could recall in history no other case of a nation’s declaring war on a lone individual. I was impressed.”

But when his bank balance ran low—and that did not take long, given his notoriously free-spending lifestyle—Hecht began to feel the sting of the boycott. “The movie moguls, most of them Jews for whose pockets I had netted over a hundred million dollars in profits with my [scripts], were even nervous of answering my hellos, let alone of hiring me. Hire me and jeopardize their English markets—what movie-making Jew was crazy enough for such a gesture!” The only way Hecht could find work was by cutting his usual fee in half and agreeing that his name would not appear in the credits. He became the Zionist equivalent of the Hollywood screenwriters who, because of their real or suspected Communist affiliations, had likewise been forced to write anonymously for the major studios.

One of Hecht’s few public allies was New York Times Hollywood correspondent Thomas F. Brady, who suggested that leaders of the British film community were being hypocritical by criticizing the anti-Communist blacklist in Hollywood while themselves blacklisting Hecht. Brady found an unnamed “film producer close to the situation” who asserted: “In both instances, there exists the effort to deprive men of the right to work because their ideas are repugnant to a majority. If Hecht’s extra-professional behavior is a legitimate reason for keeping his photoplays off the British screen then what position will Americans be justified in taking of the picture which an English company has engaged Edward Dmytryk to direct?” (Dmytryk was one of the original “Hollywood Ten” who refused the demand of the House Un-American Activities Committee that they provide the names of Communists in their industry.)

“Britain, particularly the unions and some in the Labour Party, was sympathetic to expatriate directors or writers who came to the U.K. rather than cooperate with the authorities,” Brian Neve, who teaches film at England’s University of Bath, told me. His University of Sussex colleague Frank Krutnik notes that “the British left-wing press was quite vocal in objecting to those who collaborated with the House Un-American Activities Committee—and the visit to the U.K. by HUAC spokesmen Roy Cohn and G. David Shine led to substantial public protests.” Krutnik says that the anti-American mood provoked by the Cohn-Shine visit in 1953 even led to some booing and heckling of Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis when they performed at the London Palladium shortly afterward.

While many in England were indignant that Hollywood figures might be penalized for their pro-Communist opinions, that outrage evidently did not extend to the issue of penalizing Hecht for his militant Zionist opinions. Although the British boycott “made my income a constantly precarious matter,” Hecht stuck to his guns. He wrote screenplays under other names, or no name at all. He “outwitted the empire that was gunning for me” by writing under his own byline “for Ben Franklin’s old weekly, The Saturday Evening Post and Collier’s, [which] were not ready to trim their literary policies to British boycotts.” And he steadfastly refused to utter a word of regret for what he wrote about the Jewish revolt in 1947.

The boycott continued for four years. “Long after the British had forgiven all the other Jews who had battled them—allowing even [Irgun leader] Menachem Begin to publish his memoirs in London—they continued to berate and boycott me as if, God save me, I was busy shelling the coast of Albion with some private cannon,” Hecht wrote. By 1952, the anti-Hecht boycott had run out of steam and was quietly lifted, while his spirit of principled defiance became a central part of his legend.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Rafael Medoff is director of The David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies, in Washington, D.C. His latest book is FDR and the Holocaust: A Breach of Faith.

Rafael Medoff is director of The David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies, in Washington, D.C. His latest book is FDR and the Holocaust: A Breach of Faith.