Beethoven and Freedom

On the composer’s 250th birthday

On Christmas Day 1989 after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Leonard Bernstein conducted Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, with its setting of Friedrich Schiller’s Ode to Joy:

Joy, immortal incandescence!

Daughter of Elysium!

Drunk with fire from thy presence

To thy temple ground we come …

“Freude”—Joy—is the subject of Schiller’s ode, but Bernstein substituted the word “Freiheit”—Freedom—in his festive rendering of the work. That fit the occasion, but it also paid tribute to Beethoven himself, lauded as the composer of freedom by writers too numerous to mention.

There are rare moments when the triumph of the human spirit lifts us into a higher state of being. We look at perfect strangers and see the better angels of our nature, and shed the pettiness and petulance of daily life. We feel the touch of the infinite and feel the fullness of our freedom, because man is only free as a moral agent. And in such moments we hearken to the composer of freedom, whose 250th birthday falls this Dec. 16. People of good will everywhere will celebrate this anniversary with gratitude. I owe a personal debt to Beethoven, the guide and comfort of my youth, and in his honor I offer a thought about his music: It isn’t only that Beethoven was an apostle, or an exemplar of freedom, but that his music actually summons us to freedom.

Above my piano hangs a charcoal portrait of the composer, a bar mitzvah gift from my childhood teacher, signed by “Beethoven’s pupil’s pupil’s pupil’s pupil.” Beethoven’s personal influence radiates through the 19th and 20th centuries so broadly that it is hard to avoid. Beethoven’s student Carl Czerny taught Franz Liszt as well as Theodor Leschetizky, the most prolific piano teacher of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Leschetizky in turn taught Mieczyslaw Horszowski, who accompanied Pablo Casals when he played at the Kennedy White House. Horszowski—whom I heard in concert when he was nearly 100 years old—taught the Italian pianist Carlo Levi Minzi, who taught me. Levi Minzi’s main teacher was the Swiss pianist Paul Baumgartner, a student of Walter Braunfels’, yet another Leschetizky pupil. I also studied with Niels Ostbye, a student of Edwin Fischer, in turn a pupil of Liszt’s pupil Martin Krause.

Not that I am worthy of my teachers or my yichus, but through them I learned something from Beethoven: We may judge what is merely beautiful, but sublime art judges us, or better said, it challenges us to judge ourselves.

Engagement with sublime music has something in common with Jewish prayer. As the late Rabbi Joseph Hertz wrote in the introduction to his edition of the siddur: “If in Greek the root-meaning of the verb, ‘to pray,’ signifies ‘to wish,’ and if in German it means ‘to beg,’ in Hebrew, the principal word for prayer comes from the root, ‘to judge,’ and the usual reflexive form (hithpallel) means literally, ‘to judge oneself.’ The word tefillah, ‘prayer,’ has therefore been understood as ‘self-examination’—whether we are worthy of addressing the Holy One, who demands righteousness and holiness of life from His worshippers.”

I learned something from Beethoven: We may judge what is merely beautiful, but sublime art judges us, or better said, it challenges us to judge ourselves.

Beauty may be in the eye of the beholder, but the Sublime requires a highly specific response from the audience. In 1790, Beethoven was a 20-year-old virtuoso from the provincial German Rhineland newly arrived in Vienna, Europe’s musical capital, when the philosopher Immanuel Kant published his Critique of Judgment. The term “Beautiful” applies to finite objects that fall within our understanding: a flower, a tree, a melody. But there are natural phenomena that confront us with the infinite, which our senses cannot take in and our understanding cannot grasp. The Sublime “expands the soul,” and is “directed to giving supremacy over sensibility to the intellectual side of our nature and the ideas of reason.” Kant’s Sublime with its intimation of the indefinite is a world beyond the Greek notion of beauty; the closest approximation we find to it in antiquity is St. Augustine’s discussion of “number of the intellect” in poetry in the sixth book of De Musica.

The Sublime challenges us to conceive of something that transcends the way we process sense information. Because the Sublime demands our intellectual response, it evokes freedom: We are not the passive observer of fixed and limited phenomena, but the artist’s collaborator in the recreation of the art work. We must lift our spiritual level to engage it. Kant’s most striking example is the biblical prohibition of images: “Perhaps there is no more sublime passage in the Jewish Book of Law than the commandment: Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven or on earth, or under the earth. ... This commandment can alone explain the enthusiasm which the Jewish people, in their ethical period, felt for their religion ... The same holds good of our representation of the moral law and our innate capacity for morality.”

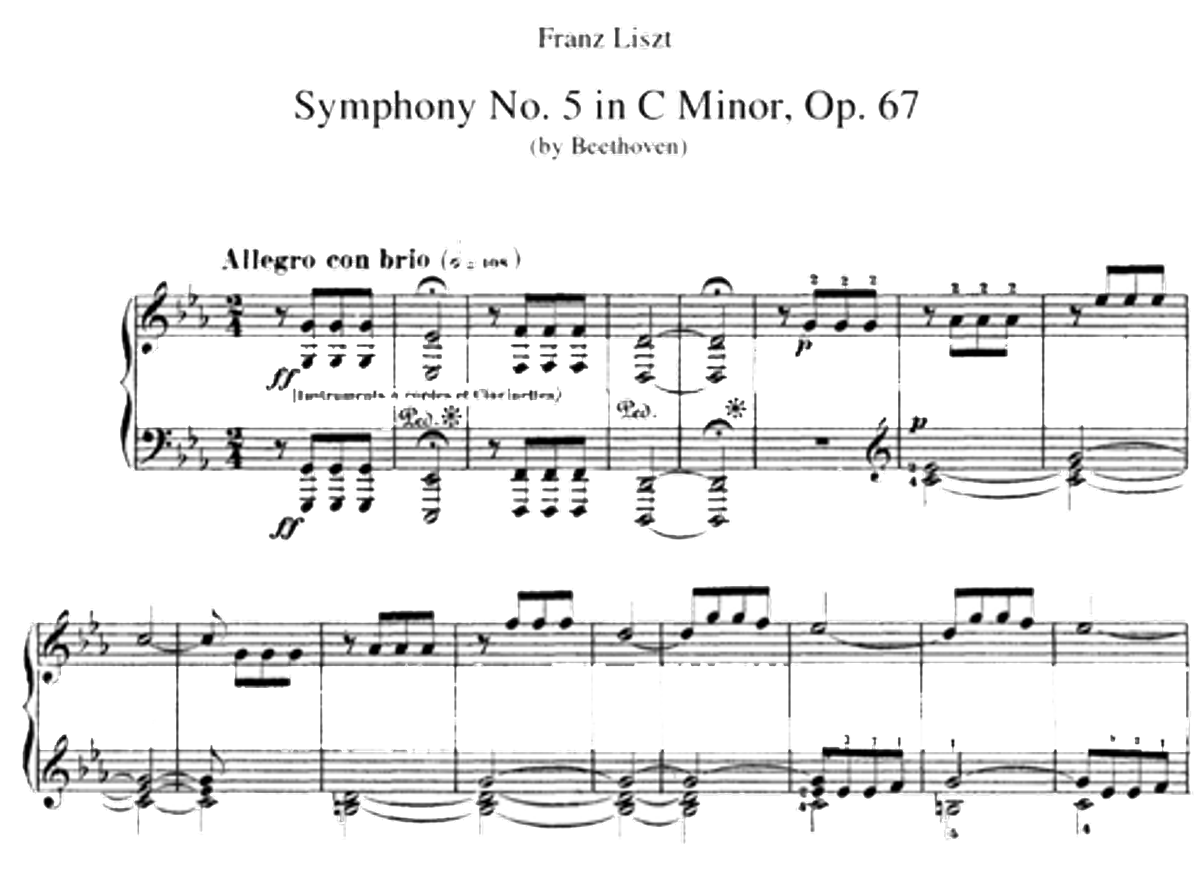

The great composers create a sense of the infinite within the finitude of classical form, by manipulating musical time. Traditional as well as pop music work within the confines of regular time and fixed meter. Time itself becomes malleable in Western classical music. Mozart plays with time like a minor god; Beethoven challenges it directly. In his most characteristic works he presents the simplest possible musical material and subjects it to radical metrical transformation. We hardly can speak of a “theme” in the famous first subject (“Da-da-da-Dah”) of the Fifth Symphony (below in Franz Liszt’s piano transcription):

The four-note opening motif is repeated, then compressed into metrical straits that bring us to the second theme in the relative major before we know it. The metrical signature of the first theme is intertwined with the new theme in the major, and leads to a development section of extraordinary length and complexity.

Everything in Beethoven’s harmonic language was already there in Mozart, but the younger composer makes a different musical point: Everything is change, and everything is transformation. The continuous transformation works so well precisely because it is embedded in the harmonic structure and formal organization of the sonata. He skates on thin ice, but the ice is always beneath him. Wagner is something like Beethoven, but without the ice. However Beethoven rouses our emotions, he demands that we think about what we hear. Wagner invites us to drown ourselves in a timeless emotional miasma.

This sacrifice of thematic substance to transformation of the musical material makes its first appearance in the 25-year-old Beethoven’s first published work, the piano trios Op. 1, in the third of the group. His teacher Joseph Haydn advised him not to publish it, not because Haydn thought it poor, but because he feared the public would not understand it. But the old composer’s caution was misplaced, and the edition sold out. The zeitgeist favored change—the French Revolution was then in mid-course—and Beethoven’s public responded to the composer’s demands.

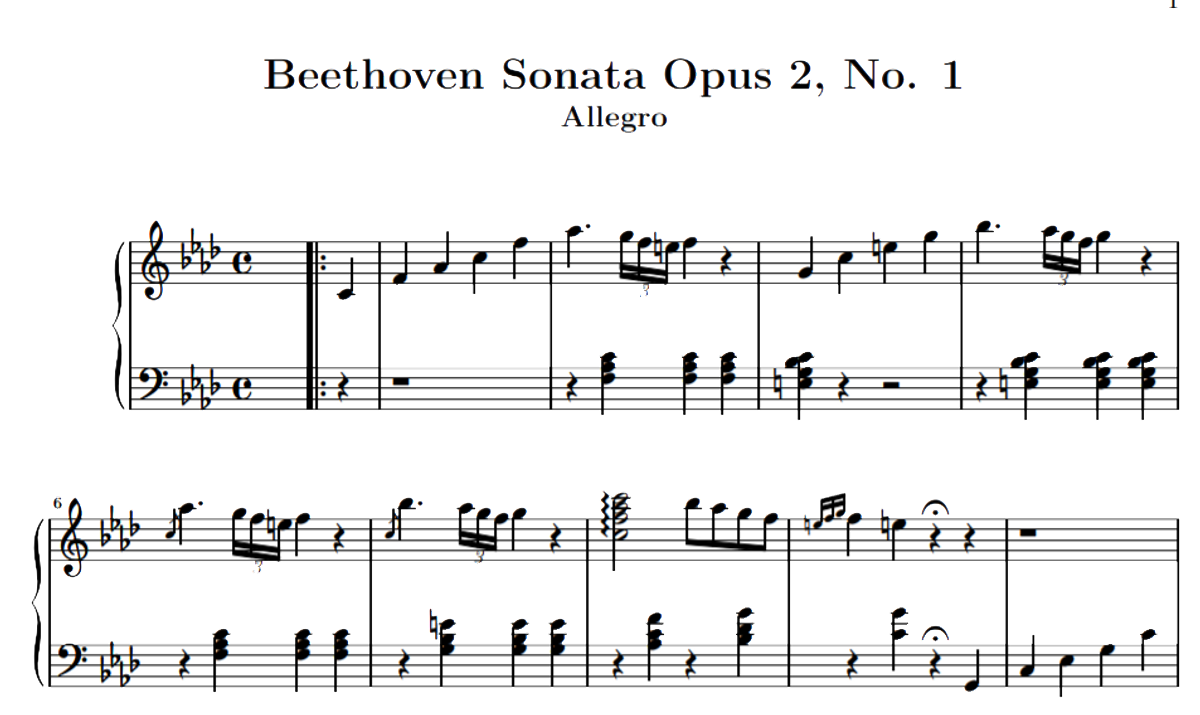

When Niels Ostbye taught me Beethoven’s first piano sonata, he observed that nothing like it had ever appeared before, and that he knew this to be true, because he had reviewed the whole preceding sonata literature. We have the same device as in the Fifth Symphony: The barest melodic material stated, repeated in the dominant, and then condensed in time.

The Third Symphony (“Eroica”) initially bore a dedication to Napoleon, erased after the French ruler styled himself emperor. Here Beethoven chose to extend time rather than compress it; the arpeggiated E-flat major chord that appears as a first theme was, again, like nothing the public had heard before. The expansiveness of Beethoven’s thematic material supported a divine length that baffled the 1805 audience.

The critic of the Vienna Freymüthige sneered, “One group, Beethoven’s very special friends, maintains that precisely this symphony is a masterpiece, that it is in exactly the true style for more elevated music, and that if it does not please at present, it is because the public is not sufficiently educated in art to be able to grasp all of these elevated beauties. After a few thousand years, however, they will not fail to have their effect. The other group utterly denies this work any artistic value and feels that it manifests a completely unbounded striving for distinction and oddity, which, however, has produced neither beauty nor true sublimity and power.” The Algemeine musikalische Zeitung wrote that “the symphony would improve immeasurably (it lasts an entire hour) if B. could bring himself to shorten it, and to bring more light, clarity, and unity into the whole.”

If the critics of 1805 disdained the “Eroica,” what would they have made of Beethoven’s last piano sonatas? The second movement of his last sonata Op. 111 is a theme and variations (played by Rudolf Serkin here starting at 9:22), whose last iteration breaks down the musical material of the theme (at 18:00), and ultimately then recalls it in augmentation over a trill that seems to stretch into infinite time (starting at 21:30). If infinity is the hallmark of the Sublime, Beethoven’s valedictory statement in the piano sonata is the exemplar in the piano repertoire.

A character in Thomas Mann’s Doktor Faustus claims that after this, there were no more sonatas left to write. That is clearly wrong; Schubert, Schumann, and Brahms reinvented the sonata yet again. But the Op. 111 was an epochal work that raises the receptive listener to a more exalted state of Being. It does so by transforming our time awareness, and in that precise sense it summons us to freedom. As Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik taught, “Time-awareness also contains a moral element: responsibility for emerging events and intervention in the historical process. Man, according to Judaism, should try to mold and fashion the future.”

By evoking the infinite out of finite temporality, Beethoven gives us not just an impression, but rather an existential participation in freedom. The composer confounds our expectations and plays hob with our temporal perception, demanding that we follow him through warps in the space-time continuum. In the Op. 111 he shows us that mortal man can achieve a presentiment of the infinite out of finite materials. But the Sublime also has a dark side. No pianist has captured this better than the Chinese virtuoso Yuja Wang, whose 2016 reading of his “Hammerklavier” Sonata Op. 106 astonished the musical world. Beethoven presents a fugue in the fourth movement, but a fugue of a kind that no one had heard before or since, a mad concatenation of twists and turns of impossible extension (listen to Wang’s performance on YouTube at 33:53).

The technical demands of the “Hammerklavier” deterred pianists from offering it in public until Franz Liszt played it in Paris in 1836. But it is not Wang’s technical mastery that makes her reading so persuasive, but rather her affinity for Beethoven’s humor. She dresses for concerts in impossibly short backless gowns and stiletto heels, mocking the devotional solemnity with which her peers approach the classics. Her irreverence captures the late Beethoven—deaf, isolated, and sometimes bitter—better than the piety of her Western peers. The same gnomish, lachen mit yashcherkes side of Beethoven appears in the Op. 119 and 126 Bagatelles, and the C# Minor Quartet Op. 131. Some of his late works in my view are failures, including the “Great Fugue” Op. 133, and the “Missa Solemnis.” Until the estimable Ms. Wang taught me better, I thought the “Hammerklavier” a failure as well. It isn’t; rather, it’s a monument to Beethoven’s exasperation with his audience.

Beethoven remains sublime even in his darkest moments. The sublime is not comforting, but rather disturbing, as Friedrich Schiller explained: “The feeling of the sublime is a mixed feeling. It is at once a painful state, which in its paroxysm is manifested by a kind of shudder, and a joyous state, that may rise to rapture, and which, without being properly a pleasure, is greatly preferred to every kind of pleasure by delicate souls.”

The Ninth Symphony calls out to us from a lost epoch of optimism borne by the American and French revolutions. “Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive/But to be young was very heaven,” Wordsworth wrote. In his choral setting of Schiller’s Ode Beethoven dwelt on the words, “Be embraced, you millions. World, do you sense the creator? Seek him above the canopy of stars! He must abide above the stars!”

The poem’s gushing enthusiasm clashes with our cynicism; we barely can read it today without a smirk—except, of course, when the Berlin Wall came down. Kant’s hope that the proliferation of republics would lead to a “perpetual peace” and Schiller’s universal embrace seem like quaint fossils left over from the Enlightenment. Napoleon wasn’t exactly Moshiach, as Beethoven’s generation learned to its sorrow.

The 20th century mocked Beethoven’s hope. A 1942 newsreel shows the great Wilhelm Furtwangler under a giant swastika conducting the Berlin Philharmonic in Beethoven’s Ninth, in honor of Hitler’s birthday. An indifferent Joseph Goebbels lurks in the front row. It is satanically grotesque to watch the Nazi brass listen to Schiller’s declaration, “This kiss to the whole world!” Even the greatest art must be rooted in the ethical practice of living communities, or eventually it will be perverted to wicked purposes. The German Enlightenment failed the Jews. The great Moses Mendelssohn, “the German Socrates,” was a punctiliously observant Jew as well as an inspiration to Kant, but his son converted to Christianity. His grandson was the composer Felix Mendelssohn.

The Beautiful isn’t the Good, contrary to the Greeks. Hitler could enjoy a rose as much as the Chofetz Chaim. Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik wrote, “Beauty itself is in need of redemption. There is so much primitive, cold, cruel, scheming and treacherously false beauty that it is comical to speak about the high potential of remedial energy in beauty. Was not Delilah lovely? Does not the Book of Esther tell us about the developed sense of beauty of King Ahasuerus. ... Is beauty good, and art cathartic, by its very nature?”

And that is why I am an observant Jew first and a musician second. My tshuvah in middle age taught me (as Eugene Rosenstock-Huessy put it) that “no skyscraper, no man-of-war, no Venus of Cnidus, and no glory of arms is more important than the tears of the widow or the sigh of the orphan.” We look forward to a world where all humankind will call on the one God by his right name, but we do not—or at least should not—confuse our apocalyptic hope with the world we actually live in, and cleave to our own particularity.

But that does not diminish my debt to Beethoven, my boyhood inspiration. On the contrary: As I deepen my Judaism, I love and understand him better.

David P. Goldman, Tablet Magazine’s classical music critic, is the Spengler columnist for Asia Times Online, Washington Fellow of the Claremont Institute, and the author of How Civilizations Die (and Why Islam Is Dying, Too) and the new book You Will Be Assimilated: China’s Plan to Sino-Form the World.