Beginning of the End

Decadence and anti-Semitism in Arthur Schnitzler’s Vienna

One hundred years ago, Arthur Schnitzler published his most ambitious novel, The Road into the Open. He declared it his most personal work; it would be his least understood. It was like his other work in that it portrayed an affair between an aristocrat and a woman of the lower middle class—a subject he claimed as his own in the cynical, melancholy comedies that had made him one of the most popular playwrights of the Austrian fin de siècle. It was unlike his other work in that it depicted Viennese Jews struggling to breathe in an atmosphere poisoned by anti-Semitism.

The readers of Schnitzler’s day were not ready for this. They found The Road into the Open perplexing, and mostly ignored it, passing on that neglect to posterity. Many decades would pass before scholars of another era would restore the book to its central place in Schnitzler’s oeuvre. A new translation by Roger Byers was issued in 1992 by the University of California Press. It tried to improve upon the only previous English translation, from 1923, by recreating in English the music of the German original. It introduced a new generation of readers to a unique work deserving of a still wider readership—the only enduring novel written in any language before 1945 which highlights urban Jewish intellectuals of the pre-1914 period,” the cultural historian William Johnston wrote in his introduction to the 1991 Northwestern University Press edition, and the only prose fiction in which Schnitzler portrayed an entire social world.

By 1908, in Parliament and on the streets, the terminal descent into class warfare and race hatred that would tear the Austro-Hungarian Empire apart had already begun. The city was governed by an avowed anti-Semite; its gutter press was filled with attacks on the Jews; German and Slavic nationalists exchanged bloodthirsty invective in Parliament. A 19-year-old Adolf Hitler arrived in Vienna that year and found there, fully formed, the rhetorical arsenal that he would brandish in a later time and a different place.

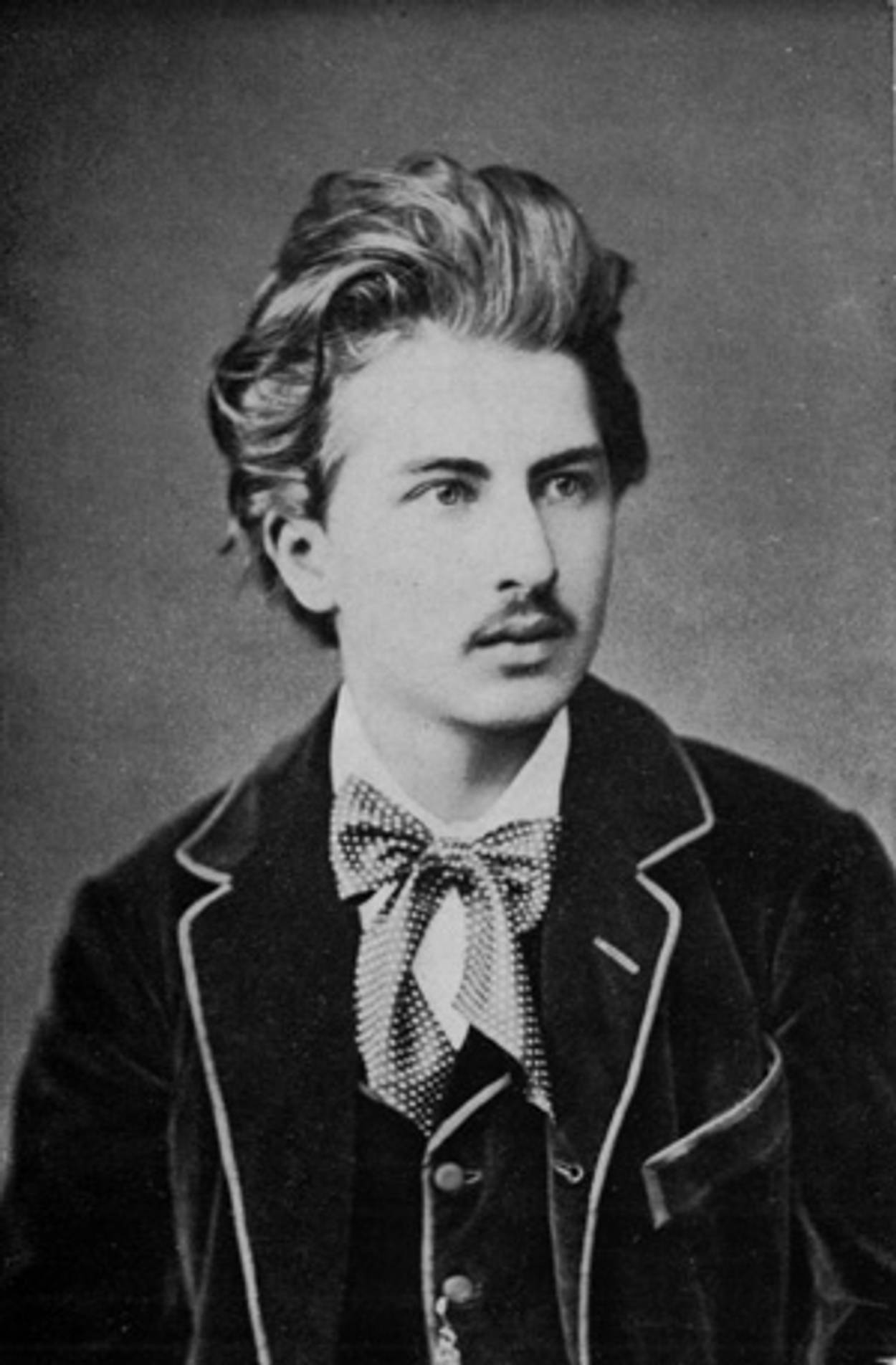

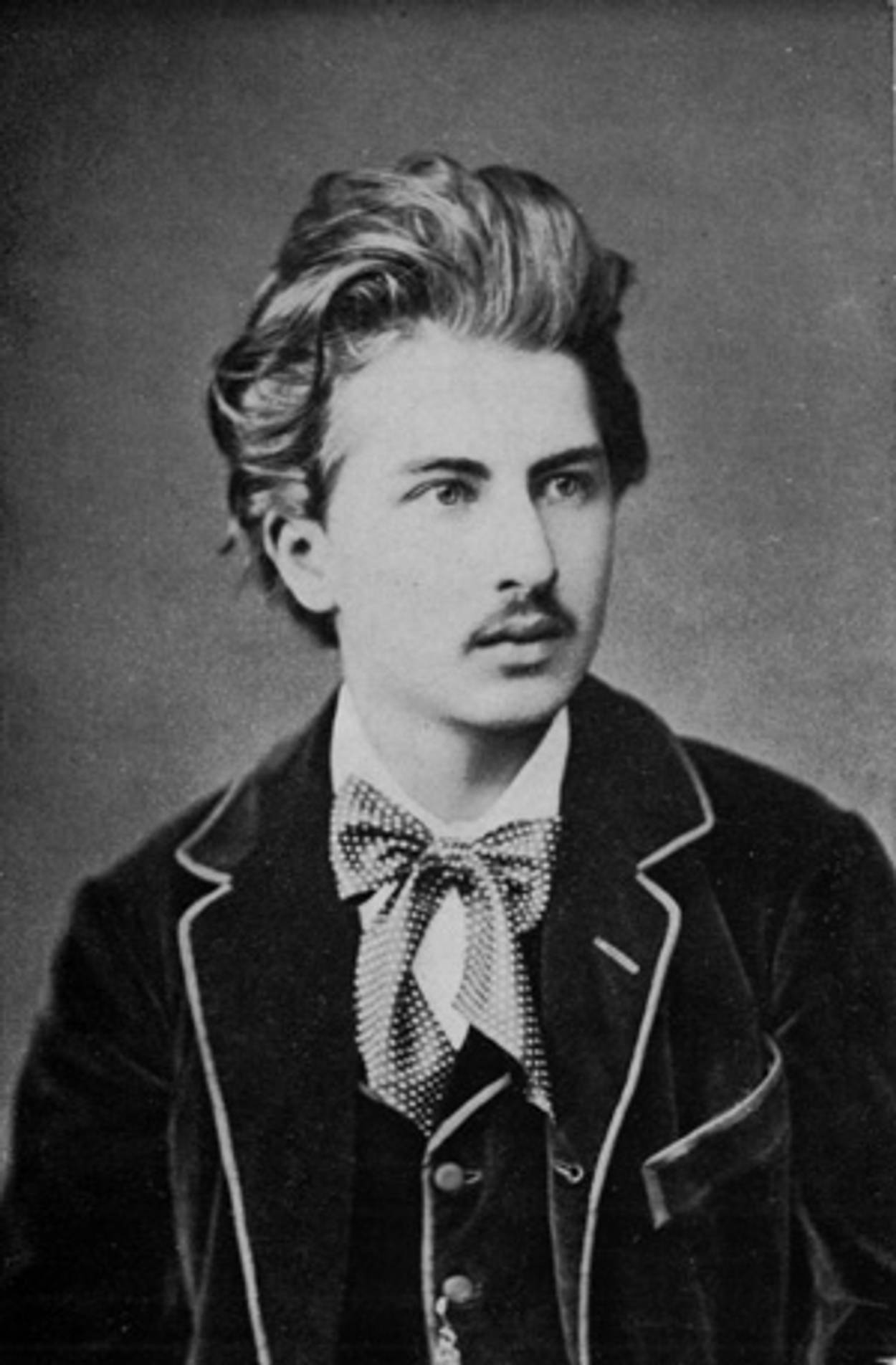

Then again, the Christian Socialist mayor Karl Lueger—charming, elegant, much beloved in the city—pursued no discriminatory policies against Jews, dined with them openly, collaborated with them in the governance of the city, and harmed no one on the basis of their race or nationality. And Vienna was home to the largest Jewish middle class in the world. Nowhere else had Jews progressed so rapidly, prospered so well, or assimilated so quickly. Schnitzler was a characteristic product of this milieu. Born into the Jewish quarter of the city, the Leopoldstadt, in 1862 (when it was still a quite elegant neighborhood,” he observed in his memoirs) to a prominent laryngologist who counted many of the city’s theatrical stars among his clients, he was raised in privilege, followed his father into medicine, and trained in the same psychiatric clinic as Sigmund Freud. He allied himself with the aesthetic revolutionaries who named themselves Young Vienna, chased women (he was one of the great erotomaniacs of his age, meticulously recording each of his orgasms in a diary), and strode into a successful literary career.

And yet this unbroken record of pleasure and success was shadowed by fear. Prosperous and fully enfranchised, the Jews of Vienna bore a crushing psychic burden that distorted their relations to themselves and others. Speaking broadly,” the Gentile anti-hero of The Road into the Open, Baron Georg Wergethin, observes early on of the Jewish friends that surrounded him, he found their tone to each other now too familiar, now too formal, now too facetious, now too unsentimental; not one of them seemed really free and unembarrassed with the others, scarcely indeed with himself.” In the novel, Schnitzler the former doctor lays out a clinical anatomy of the psychic scars imposed on the Jews by their liminal position as privileged outsiders in Austrian society. His characters can neither fully embrace nor wholly reject their equivocal role in an unjust and disintegrating society. They twist themselves into a fantastic array of personal and political contortions in an effort to break out of the impasse, and into the open.

Schnitzler’s Gentile baron is a privileged outsider in a world of privileged outsiders. Georg attends to the sorrows and involutions, the gossip and political disputes, of the Jewish writers and artists that frequent the salon of Salomon Ehrenburg, a munitions manufacturer. There are no observant Jews in this social milieu; the Galician immigrants who had crowded into the Leopoldstadt in the decades after emancipation (transforming the elegant neighborhood of Schnitzler’s youth) do not appear here. In a series of set pieces in the Ehrenburg salon and in Italian resorts, Schnitzler deploys a contrapuntal method to survey the full range of responses to anti-Semitism as his Jewish characters are

tossed to and fro as they were between defiance and exhaustion, between the fear of appearing importunate and their bitter resentment at the demand they must yield to an insolent majority, between the inner consciousness of being at home in the country where they lived and worked, and their indignation at finding themselves insulted in that very place.

Salomon Ehrenburg’s son Oskar represents capitulation: he aspires to be absorbed into the Catholic aristocracy; only the threat of disinheritance prevents him from converting. The beautiful Therese Golowski has become a leader of the Social Democratic movement, though her passion for social justice conflicts with her taste for beauty and luxury. (She will either end up on the scaffold, or as a Princess,” another character predicts.) When we first learn of her, she has been imprisoned for defaming a member of the royal family at a coal miner’s strike; later, she appears at an Italian resort on the arm of a famous aristocratic horseman. Her younger brother Leo is serving as a military officer in the east. Though possessed of all the courtly virtues, he has become a fervent Zionist, and embraces the cause of the Galician masses yearning for a return to their spiritual homeland. He embodies the spirit of Jewish self-assertion. He will go on to challenge an anti-Semitic persecutor to a duel, and shoot him dead.

Georg draws closest to the novel’s most complex and most tortured Jewish character, the playwright Heinrich Bermann. His satirical plays, like Schnitzler’s, have been attacked by the conservative and clerical press. He admits to Georg to being adversely affected by the attacks, and, speaking on behalf of the Jews, tells him: It doesn’t take much to awaken the self-contempt which is constantly lurking in us; and once that happens there is hardly a fool or scoundrel with whom we are not ready to take sides against ourselves.” Bermann manages his tortured Jewish self-consciousness through brutal candor. He is free with criticism of himself and others, and he does not exempt his co-religionists. Characteristically, his statement of Jewish pride takes the form of an avowal of hatred:

There are Jews who I really hate, hate as Jews. They are those who behave in front of others, and sometimes among themselves, as if they weren’t Jews at all. Who try to appease their enemies and despisers in a cheap, cringing manner and think they can ransom themselves like this from the eternal curse, which weighs on them, or from that which they only feel as a curse.

Bermann has watched anti-Semitism destroy his father, once a successful lawyer, who was driven out of the German Liberal Party and financially ruined when his clients desert him. Bermann is keenly aware that even the best-intentioned Gentiles, such as Georg, are not immune to it. But he rejects the Zionist enthusiasms of Leo Golowski with equal fervor. In a lengthy colloquy with Leo, Bermann avers that to depart Austria for a desert under the rule of the Ottoman sultan would be a capitulation to the worst of the Jews’ enemies. He insists on his right to live in Austria. He would accept Zionism as a moral principle and as a welfare scheme if it would honestly make itself known as such; but the idea of the establishment of a Jewish state on religious and national grounds appeared to him an insane revolt against the spirit of all historical development.”

Running parallel to Georg’s social life among the Jews is a sad and chastened account of his affair with Anna Rosner, a music teacher from a lower-middle-class German family. The young Schnitzler had inveighed against the hypocrisy of the old Victorian sexual morality, though not without acknowledging the dangers of unleashing the instincts. In The Road into the Open, Schnitzler pits fathers and sons, Gentile and Jew, in a series of exemplary generational conflicts that seldom redound to the credit of the sons.

Georg impregnates Anna, and takes her on a journey to hide the fact. He does not know whether he will marry her. Much of the novel is consumed by lengthy accounts of vacillation and drift. He is haunted by the memory of past affairs. If the world were coming to an end tomorrow,” he muses, not long after learning of the pregnancy, It would be Cissy I’d choose to spend the night with me,” speaking of a minor personage on his social scene.

This hesitation is shocking to the elderly Doctor Stauber, a friend of Georg’s deceased father, who tries to shame him into marrying Anna: Just think for a moment how your blessed Herr father, who didn’t even know Annerl, would have felt about the matter. He was surely one of the brightest men, and the most free of prejudice, that one can think of. And despite that, don’t think for a moment that it would be completely without shock even to him.” Stauber’s tone is at once condemnatory, beseeching, and self-effacing. He knows that sexual mores have changed, that his shock is a product of another world in which certain concepts stood authoritatively firm, when everyone knew quite well: one must honor one’s parents, or else one was a lout…or: a true love comes once in one’s life…or: it is an honor to die for the Fatherland…” He knows that it is impossible to invoke such concepts without self-irony, that they have lost their morally coercive power over a younger generation that has freed itself from the influence of the fathers.

A possibility of this new freedom was that the surfeit of possibility itself could paralyze the will, and evacuate the heart. This incapacity recurs elsewhere in the novel. Time and again, the young fail to rise to the standards of decency set by their parents. Stauber rallies to Anna’s side in her time of need. Anna’s parents bear the burdens of their misfortune humbly. Her lazy, resentful brother Josef embarks on a career with an anti-Semitic newspaper owned by the demagogic Alderman Jalaudek. Bermann confesses that receiving the news of his father’s death troubled him less than his concern over new developments in his latest affair with an actress.

Schnitzler’s dialectical method has a way of destroying all contrasting arguments; neither assimilation nor resistance, flight nor defiance, the worker’s utopia nor the embrace of German culture will deliver these characters into the open. The malign stasis of Viennese political life never resolves. The characters continue to drift, avowing causes and living lives for which they are each, in different ways, temperamentally unfit. Georg’s domestic drama finally concludes in sterility and death. His child is stillborn in a rented house on the outskirts of Vienna. He will not marry Anna. He gazes on his dead child and is overtaken by sorrow, as he gazes at a future that will not be born:

There lay this sweet, tiny body, which was ready for existence, and which now could not move. There shone large, blue eyes, as if longing to drink in the light of the sky, blind as death before they had ever seen a single ray. There opened, as if thirsty, a tiny, round mouth, which would never be permitted to drink from the breast of a mother. There stared this pale child’s face, with fully formed human features, that would never receive and experience the kiss of mother or father. How he loved this child! How he loved it, now that it was too late.

Wesley Yang has written about books and culture for the Boston Globe, the Los Angeles Times, the New York Observer, and n+1.

Wesley Yang is the author of The Souls of Yellow Folk.

Wesley Yang is the author of The Souls of Yellow Folk.