Should American Jews Speak Hebrew?

Israeli Jews and diaspora Jews: one people divided by a common tongue

Before 1948, David Ben-Gurion used to joke about Zionism’s future: How will we know when we have become a real country like the rest of the world? When Jewish thieves and Jewish prostitutes conduct their business in Hebrew—and Hebrew-speaking policemen arrest them. Nowadays, the joke, possibly apocryphal, falls a bit flat. The State of Israel is a reality, and more people read and write, argue and pray, think and dream in Hebrew than at any other point in Jewish history. Nor are crime and punishment in Hebrew something exceptional. Indeed, they are all too familiar as Israel grapples with its local mafia kingpins and struggles against Palestinian terrorists, many of whom speak fluent Hebrew. The dramas of Israel’s future seemingly lie elsewhere in the realms of religion and politics, security and statecraft.

And yet the very success of the Hebrew revival obscures its broader consequences for the relationship between the Jewish people and Israeli statehood. The ideal of a Hebrew-speaking country, after all, derives its force from the image of Jewish autonomy, a self-contained world enclosed in its own Hebrew domain. Yet language always functions as a double-edged sword: In one stroke it unites a national community by severing their cultural ties to the world around them.

For Jews, however, the reacquisition of language has brought an unexpected corollary. The same Hebrew language that provides the vital connective tissue necessary to realize Jewish nationhood also splits the Jewish people in two. Since 1948, one half of the Jewish world not only lives beyond Israel’s borders; it also lives outside the Hebrew language. That fact merits much more commentary than it receives in our never-ending debates about Israel-diaspora relations. If we wish to chart the future of Jewish peoplehood in Israel and beyond, we must first wrestle with the strangest irony of the present: Jews are becoming a people divided by a common language.

***

The question of language first surfaced in the great debate between Ahad Ha’am and Theodor Herzl over the future of Zion in the opening years of the 20th century. In his 1902 German-language utopian novel, Alteneuland, Herzl outlined a detailed vision of a country in which 20 years of mass immigration and technology-fueled economic growth had brought peace and prosperity to all of its inhabitants. Jews, Muslims, and Christians happily coexisted in a model democracy without a military. After solving their own Jewish Question, the Jews now turned to repairing the Third World. Ahad Ha’am in turn ridiculed Herzl’s fantasy of a “complete paradise,” the “most enlightened little country” the world had ever seen. Twenty years was not enough time to empty out the diaspora, he observed. The land of Israel could not sustain that rate of immigration in physical, economic, or political terms. The wishful attitude toward Jewish-Arab relations bespoke a studied naïveté incommensurate with the violent character of modern politics. Scientific futurism without roots in the past and realism in the present would lead the Jewish people to a dead end.

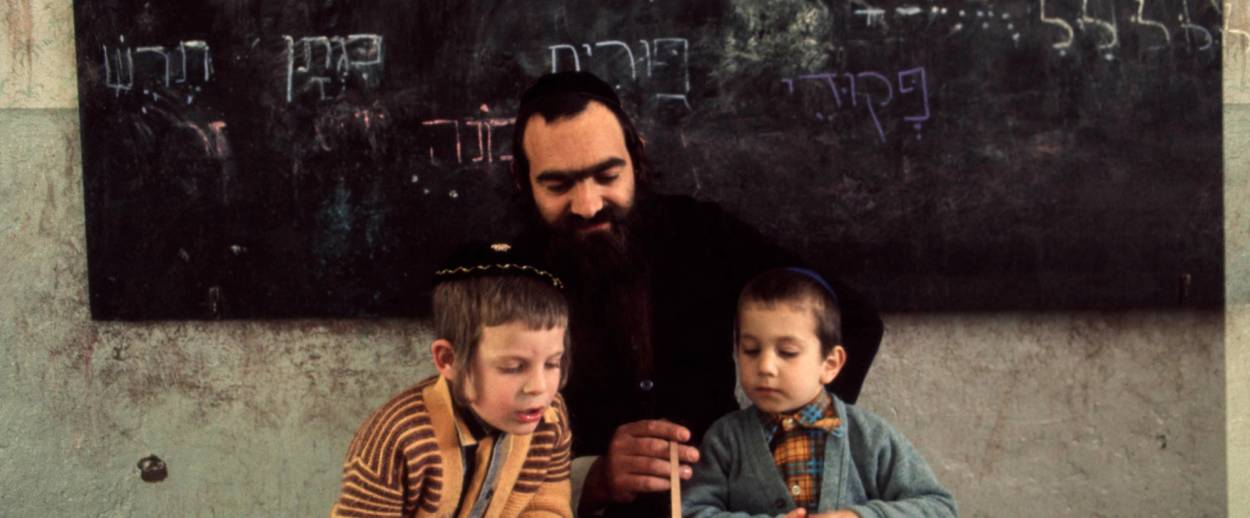

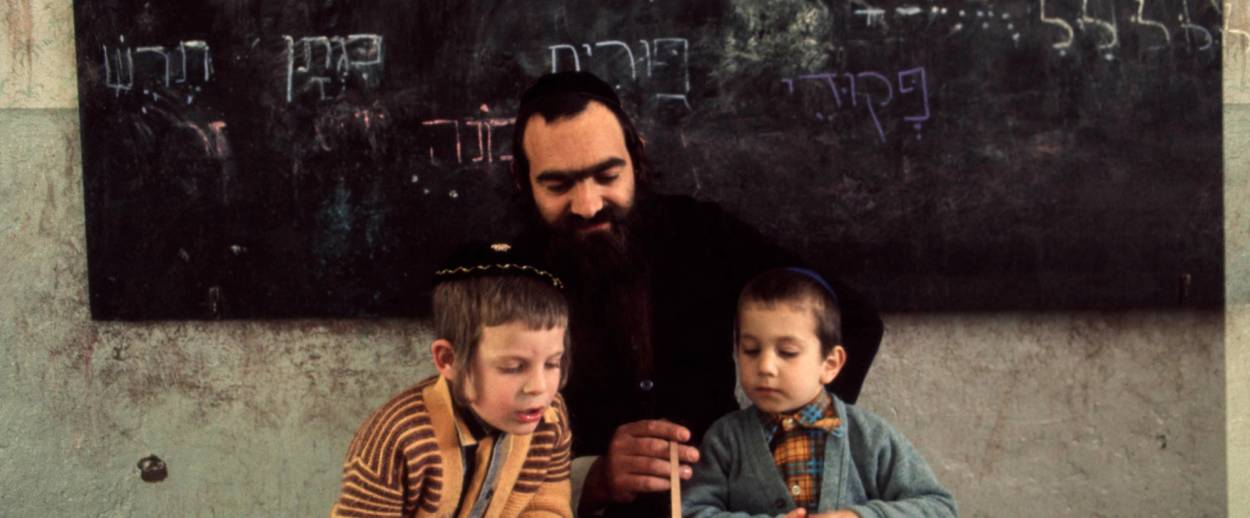

Herzl’s worst sin, according to Ahad Ha’am, was to denude his future Jewish country of the one feature that had served as the key to Jewish survival across history: Hebrew. There could be no national revival without a Jewish language in which to dream it. Form and content were linked. Language served as the carrier of Jewish ethics, the shaper of Jewish consciousness, and the necessary boundary line between Jews and the other civilizations of the world. In its absence, all the future achievements in Jewish science and culture would amount to little more than pale imitations of Western civilization.

One hundred-plus years after that first controversy, it is fair to ask: Are we living in Herzl’s dream or Ahad Ha’am’s nightmare? A case might be made that the Israel of today would prove each man half-right. Herzl prophesied peace and technologically driven prosperity. We have one without the other. The Start-Up Nation remains at war with its neighbors and riven by dangerous political fault lines. Ahad Ha’am warned of building Hellas in Zion. Modern Israel is Athens and Jerusalem rolled into one—with a heavy dose of Sparta to boot.

If Israel today partially vindicates both Herzl and Ahad Ha’am, in one respect it also flouts each of their predictions. The revival of Hebrew has hardly parochialized Israel as Herzl feared. Nor, for that matter, has it spread its spiritual influence into the world as Ahad Ha’am hoped. What it has done, however, is usher in an uncertain new chapter in the relationship between Israel and the rest of the Jewish world.

We see this most clearly in the fraught kinship of American Jews and Israel. Distancing or polarization, disaffection or apathy, advocacy or criticism—our diagnoses are many, our prescriptions equally varied. But debates over policy and ideology distract us from a deeper, longer-term reality that deserves our attention. The largest Jewish community in the world outside of Israel lives out its relationship to the Jewish State entirely in English. While Israeli society features homegrown Arab writers and politicians who argue about the justness of Zionism in the Holy Tongue, few American Jews—whatever their political stance on Israel—can do little more than order falafel in Hebrew. American Jewish leaders vigilantly scrutinize Israel’s image in American politics and media, yet they have virtually no contact with the inner life of the Israeli society they so zealously defend. Local federations and Israeli Foreign Ministry officials sponsor Israeli film festivals, concerts, and speakers—in English, not Hebrew.

It turns out that neither Herzl nor Ahad Ha’am quite anticipated the world we now inhabit. Herzl assumed that Europe’s influence would naturally extend to the realm of language, making German the lingua franca of the Jewish world. Ahad Ha’am supposed that any successful Jewish national revival would move in the other direction, with the Hebrew language colonizing the Jewish diaspora. Thus, our prophets have left us no map to guide us into the future.

***

You learn a lot about Israel today when you arrive at Ben-Gurion Airport. The long, winding corridors encircling the main waiting room lead to the massive downward-sloping ramp in the entrance hall. In the border control room, a babble of languages rises as the crowd separates into two side-by-side sets of lines, one for Israeli passports and the other for foreign passports. The sorting that takes place there follows predictable patterns. Bald men bark Hebrew into cellphones and peroxide blondes purr in Russian as they sail through the Israeli passport queue. Christian tour groups and South Asian hi-tech executives stand patiently in the foreign passport line. Arab families sit on the side, awaiting some special vetting of their own. Then there are the rest of us. Amidst this jumble, one group always stands out to me: American Jewish college students staring in mystification at Hebrew-lettered signs.

In Operation Shylock, Philip Roth points out the radical nature of American Jewish monolingualism. American Jews, Roth writes, chose “to be Jews in a way no one had ever dared to be a Jew in our three-thousand-year history: speaking and thinking American English, only American English, with all the apostasy that was bound to beget.” Roth is right that monolingualism itself is something of a modern American Jewish heresy. Multilingualism was ever a fact of Jewish life through history. But whatever language Jews spoke—Greek, Aramaic, Arabic, Yiddish, Ladino—Hebrew remained at the core of their spiritual and cultural lives, especially for educated elites. In modern America, by contrast, Jews rejected multilingualism. Instead, they elevated the embrace of English to the level of an exclusive, ideological choice.

The 2013 Pew survey found that only half of American Jews know the Hebrew alphabet. Not the language, mind you, but the alphabet. Even far fewer (13%) profess to understand the words of Hebrew when they read them. Again, the words (presumably in the prayer book), not even the spoken language. What is ostensibly the most highly educated, or academically credentialed, Jewish community in history has not learned the rudiments of the Hebrew language.

That complacency is on full display at Ben-Gurion Airport as the Birthright brigades pour out of the airport and onto their waiting tour buses. The sight always calls to mind the Teapacks song, “Ha-Loazim,” or “The Aliens” (also implying the non-Hebrew speakers). The Israeli band playfully mocks American visitors who pride themselves on saying “shalom” in Hebrew and engage in a whole host of other scripted behavior: hugging Israelis tight with cheap, condescending sentimentality, singing “Hava Nagila,” smoking the hookah water pipe, visiting Yad Vashem, and snapping a picture while wearing a kippah. As the song observes, they don’t serve in the army, they don’t buy bread at the corner market, and they can’t speak the language.

Of course, the scornful caricature of American Jews serves as a simultaneous declaration of Israeli Jewish pride—and one can easily amass a long list of Israeli stereotypes that American Jews love to mock. Yet the truth of the song lies deeper in its baseline recognition of just how much American Jews remain on the outside.

What will that entrance hall at Ben-Gurion look like decades from now? Largely the same, I reckon. Planeloads of young American Jews will continue to arrive seeking to connect with Israel. For some it will be a profound spiritual and political homecoming. For others a visit to Israel will produce a more disconcerting, ambivalent confrontation with a country they do not view as their own. Yet for all of their divisions, this mass of young people will share one thing in common: They will all encounter an Israel that welcomes them in a language they do not speak.

***

As far back as the 1950s, the great Hebraist Shimon Rawidowicz expressed the worry that the creation of Israel would lead to a binary split in the Jewish world between Israelis and Jews. He brought as evidence an anecdote about two young Israeli women in London who responded to an anti-Semitic landlord who refused to rent to Jews with a naïve, unflinching answer: “But we are Israelis, not Jews.”

Rawidowicz was both right and wrong about the danger of such a long-term trend, as it turned out. There is a massive Israeli diaspora in Europe and North America. The trend stories about the huge population of Israelis living in Berlin are by now widely familiar. Even better known is the Israeli American story. Estimates of the number of Israelis now settled in the United States range between 200,000 and 500,000 people. The recent launch of the Israeli-American Council—which seems equal parts Hebrew AIPAC and postmodern landsmanshaft—testifies to the growing self-awareness and political clout of this group.

There are many ways to parse the possible futures of these Israeli Americans. Some commentators dismiss them as yordim, the derisive term for emigrants from Israel. Embracing their U.S. passports, many of these are destined to speak a Hebrew-English mashup akin to Spanglish. This is something you can already detect in the patchy Hebrew of adult Israeli Americans raised here, who speak in Hebrew but think in English. Others note how cohesive Israeli Americans remain. Like generations before them they fashion immigrant enclaves and remain deeply attached to Israel through family, dual citizenship, and Hebrew-language media.

The largest Jewish community in the world outside of Israel lives out its relationship to the Jewish state entirely in English.

But of course, eventually one must reckon with physical space. The sight of parents coaching their children at Ben-Gurion Airport on the inevitable questions about Israeli passports, army service, and citizenship law highlights the complicated transnational character of this particular community. The Law of Return was envisioned as a one-way entry ticket into Israeli citizenship. The idea of exit was never part of the plan. Israeliness without Israeli citizenship brings us into terra incognita.

What, then, will these Israeli Americans look like 20 or 30 years from now? It is not hard to imagine that we will see Israeli Americans split into two groups on the basis of their choices vis-à-vis Hebrew. One portion will treat Israeliness like an Old World identity and Hebrew like a heritage language. Securing themselves with single citizenship, they will dissolve into the broader mass of American Jews with real but thinning ties to Israeli society.

The other Israeli Americans will place Hebrew at the core of their lives, cultivating a strong bilingualism. This Hebrew-speaking cohort, I suspect, will continue to identify closely with Israel and at the same time build themselves into diasporic Jewish communal life. Frequent family travel to Israel and summer camps will keep them and their children rooted in Israeli society.

Israeli Americans will also inevitably renegotiate their relationship to American Jewish life. In 2017 the U.S. Census Bureau floated (and eventually abandoned) the idea of adding “Middle Eastern or North African” to its list of identity boxes, with “Israel” as one of the suboptions, along with Palestinian, Egyptian, Syrian, and Iranian, among others. There is a great irony in this proposal. Decades back, American Jews fought a tough legal fight to keep Jewishness off the census. A religious category was viewed as jeopardizing Jewish political security in American society, in part because of fears of dual loyalty charges. Now, Israelis would have an option to choose legal recognition by the U.S. government. Would Israeli Americans embrace this option? Perhaps. Should it ever come to pass, however unlikely, this change would only insert yet another unpredictable factor into the relationship between American Jews, Israeli Americans, and Israel. Even if they do not separate themselves off from other American Jews in this way, Hebrew-speaking Israeli Americans will present a challenge to both Ben-Gurion’s Hebrew society and the American Jewish reality when it comes to language and identity. This brings me to the final piece of the puzzle: the attitudes inside Israel toward Hebrew and Jewish nationhood.

***

Whenever I visit Israel, I am always saddest to leave. It is not the actual pangs of departure. Nor am I seized by some terrible guilt or fear about Israel’s future. What makes it so hard for me to leave is something much more mundane: the inevitable argument with airport security about language. “How come you speak Hebrew?” the screener invariably asks, to which I reply, “Why shouldn’t I speak Hebrew? I’m a Jew.” “But you’re American,” comes the retort. To that I respond: “But I’m Jewish and we’re in Israel!” In that absurd moment of debate over why it is unnatural for an American Jew to speak Hebrew, a wave of sadness washes over me. For that is when it always hits me that language has become more a source of division rather than connection between Israel and the Jewish world.

After we move past the awkward jousting about Hebrew, we settle into the more routine questions. Where do I live in the United States? Is there any Jewish community there? Am I affiliated with a synagogue? Do I have relatives in Israel? Where do they live? What are their names? And finally, the last, inevitable question: Do I have an Israeli passport? There are myriad practical reasons for this final query. Military service, taxes, visa issues, and the sheer logic of state border control. Behind the manifestly innocent, slightly absurd exchange lurks a massive security complex devoted to policing entry and exit.

To me, however, the question always smacks of the specious logic that defines the Israeli side of the equation of Israel-diaspora relations. Hebrew is for Israelis. Too much Hebrew raises a red flag. If one has taken the trouble to learn Hebrew, then the logical step is to become a citizen of the State of Israel. There is no other conceptual place to situate American Jews inside the Israeli political imaginary except as foreign visitors or potential fellow countrymen. An American who speaks Hebrew risks destabilizing that neat binary division.

There is something threatening to Israelis about American Jews who speak Hebrew; there is something threatening to American Jews, too, about the prospect of bilingualism. These reflections bring me not to the future, but once more back to David Ben-Gurion. Israel’s founding father often spoke of Zionism in terms of “the Jewish Revolution.” Other nations such as the Americans or the French had fought for freedom from the tyranny of monarchical rule. But the Jewish people revolted not against a given political system but against history itself. The result was the rebirth of their own independent political nationhood in their ancient homeland.

In his Zionist leadership, Ben-Gurion became more than the architect of Jewish statehood. He also turned himself into the great modern prophet of Jewish political sovereignty. The centerpiece of his revolutionary vision was the “complete ingathering of the exiles” from all corners of the globe in a Jewish state. It was an imperative to end the “dispersion,” the diasporic state of dependency in which Jews were reduced to the status of “aliens, a minority, bereft of a homeland, rootless and cut off,” and replace it with Jewish political repatriation.

The flip side of this centralizing vision of land and statehood was a delegitimization of diaspora. Indeed, after 1948 Ben-Gurion famously courted controversy by calling on American Jews to make aliyah. The only valid way to be part of the Jewish nation and live a full Jewish life, he stressed, was to become a citizen of the State of Israel.

Less well known, however, is the fact that Ben-Gurion did develop his own positive vision of the relationship between world Jewry and Israel in the early years of statehood. At the time he laid out a plan to link American Jews and others worldwide together in a new form of Zionism. At a famous 1950 meeting to discuss the Israeli position vis-à-vis American Jewry, Ben-Gurion told his advisers that the old definitions and models no longer applied, for American Jews were not going to move to Israel en masse. “They know the address for an Israeli visa,” he gruffly stated, and they’re not lining up to come. “We must take honest stock,” he told his confederates, “of what they can give us and what we can give to them.”

The time had come, Ben-Gurion believed, for a new “permanent partnership” to be based on three things: a deep American Jewish identification with the reborn State of Israel; study of the Hebrew Bible and its ties to the modern Israeli homeland; and an embrace of the Hebrew language. Politics and religion would stir the imagination of American Jewry. The Jewish state would be the focal point for global Jewish unity. But equally importantly, Hebrew would serve to bind together Israeli and American Jews.

Ben-Gurion never really developed this linguistic aspect of his Jewish revolution. Too many economic and political challenges got in the way. Political expediency dictated the need to secure American Jewish support without further reproaches about their collective disregard for Hebrew. The revival of Hebrew was too taxing and threatening a burden to place on the shoulders of the busy, middle-aged American Jewish communal leaders whose support he required. Ever the ruthless pragmatist, he realized that the State of Israel proved a simpler focal point for both political mythology and practical action for American Jews. In its time, that decision may have been the right one. Yet we live with the cost of it today. Ben-Gurion is long gone, his Hebrew joke with him. But his Jewish revolution remains unfinished.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

James Loeffler is the author of The Most Musical Nation: Jews and Culture in the Late Russian Empire and co-editor of The Idelsohn Project.