Ben Katchor’s Dairy Restaurant

The artist of the decade-in-the-making graphic compendium of a lost Jewish world talks about the ‘milekhdike,’ the power of the Yellow Pages, and the utility of a good place to eat

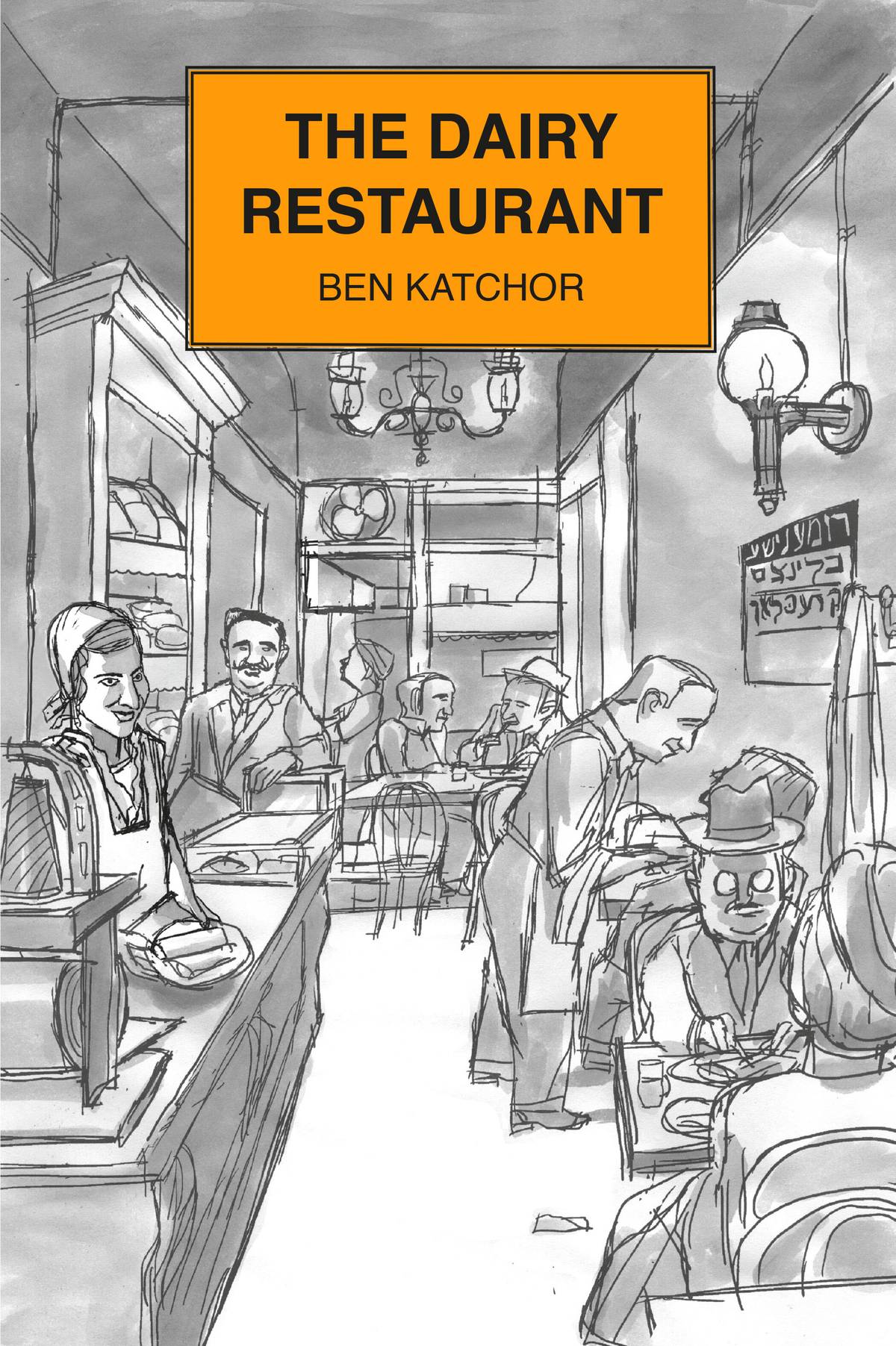

In early March, I took the subway from Brooklyn to Manhattan to meet Ben Katchor, who at 68 is as great an artist as America can claim today. Katchor’s new book, The Dairy Restaurant, was about to come out. What an achievement, I thought, this testament he’d created to a lost New York City world.

That The Dairy Restaurant (published by Tablet’s sister press, Nextbook) is not a standard comic book would come as no surprise to anyone familiar with Katchor’s unique body of work. But Katchor’s history of kosher dairy eateries is a departure even from his earlier work, which has occupied a space between early American newspaper comic strips and the comic art of “serious person” graphic novels. The Dairy Restaurant is in fact an encyclopedic history of the world comparable in its scope, though not its style, to other singular works of obsessive documentary art like James Agee and Walker Evans’ Let Us Now Praise Famous Men—a studiously constructed compendium of narrative history, sentimental fragment, artifact, restaurant memorabilia, art, and recorded fact that Katchor compares to the Yellow Pages.

In written passages interspersed with illustrations that often have the look of engravings, Katchor records the striving, teeming, Yiddish American New York that had room for both kosher dairy restaurants and kosher meat restaurants, and for the sorts of people who spent half their lives inside of such places, studying the menus, and conducting their endless, questioning discourse while picking at blintzes. Katchor has coined a Yiddish name for these people: milekhdike. The tragedy for Katchor is not only the loss of the milekhdike but the people who replaced them. “The utility of a restaurant is what I like,” he explained.

It’s about a place where you go when you’re hungry and you know there’s more to eat there. It’s not like all the things that are repulsive about affluence, or maybe it’s just called decadence, which has lost the need to feed people so it’s feeding people who don’t want to eat that much and they’re very particular about what they eat.

But the book isn’t just a nostalgia trip or a diatribe against the rich. Katchor laments the vanishing of New York’s working-class Jewish life but he also wants to know where it came from. What made the milekhdike? The answer, of course, is history.

Like any good practitioner of rational left-wing politics, Katchor is a kind of materialist. But he’s an idiosyncratic materialist, who locates the origins of the New York City dairy restaurant in the Garden of Eden—which is where Jewish dietary laws began, according to his reading of history. From there they evolved through the stages of desert wandering to the Pale of Settlement before they were finally brought from the shtetls to America by the waves of Eastern European Jewish immigrants at the turn of the 20th century.

The history and suffering and intense study habits of these unique Jews were compressed into the Formica countertops and hard plastic tables of the great dairy restaurants. These were places built by and for the working and newly middle-class Jews who gifted their culture to the rest of America while, perhaps without fully realizing it, shedding it themselves. The counters were sturdy and so were the menus—that was what made them work. You could lean on them, your food rested on them. You knew what they were there for.

Whoever truly captures the dairy restaurant, captures an entire lost world. That’s what Katchor has tried to do, and no one else could have done it.

What follows is an edited transcript of portions of our conversation.

This is a book about the very long, winding history of a particular Jewish cultural institution, the dairy restaurant, with origins that you trace from the Garden of Eden through centuries of diaspora life. Today, there are only a handful of real dairy restaurants left. Why did they disappear?

It’s working-class culture. First generation, Eastern European immigrant Jews, that’s all they could do to make a living. They didn’t want their children to do it. So the children ended up becoming doctors, lawyers, and other things.

It’s an interesting question. People talk about, what are the cultural manifestations of different classes and why there are all these things in the complacency of middle class, bourgeois culture, people despise. But then they say, “Well, so you like working-class restaurants, so you want to keep them working class.” There was an argument back in the 1920s about proletariat writers who celebrated that culture. And others said, “Wait, so you don’t want a revolution to happen? You want to keep a working class and underclass.” And that was a rebuff.

They didn’t actually know what a socialist world would be like, what kind of art will come out of that world. It won’t be working-class art but it won’t be middle class, you know, bourgeois literature. They didn’t know what it would be like. You can look at a few moments in a few places and see what it might’ve been like. Like some moments in early Soviet art where you could see what it could be—sort of experimental, and not a relaxing art. It’s the same with restaurants.

Now when I think of Jewish restaurants, other than these kinds of pizza places, maybe in Hasidic neighborhoods where there’s still sort of a working class, outside of that, it’s not a kind of place I usually want to go.

What’s interesting to me is that many of the people that have a kind of sentimental fondness for the culture of the working class—and I feel this way myself to some extent—don’t feel that for the religious working class.

Oh, I like those places. I haven’t been there lately, but I used to like Williamsburg. There are a few dairies left in Williamsburg.

Go to Kingston Avenue in Crown Heights. People talk about how the landlords are Jewish, and some of them are, but so are the locksmiths and the butchers.

That’s who does the work there; Jews. You know some of them might become doctors and lawyers, but some of them are still butchers. But in assimilated Jewish culture, that was a failure if your son stayed in a trade. Maybe you could get away with it in the arts or be a writer but not a butcher. So, you know I don’t like what happened to middle-class Jews.

The utility of a restaurant is what I like. It’s about a place where you go when you’re hungry and you know there’s more to eat there. It’s not like all the things that are repulsive about affluence, or maybe it’s just called decadence, which has lost the need to feed people so it’s feeding people who don’t want to eat that much and they’re very particular about what they eat.

The difference between affluence and decadence, in part, is where you are in the cycle. Affluence is at the top of the hill but still has some of the strength it took to make the climb and push other people out of the way. Decadence is when you’ve started the decline on the other side but you’re too comfortable to notice or care.

There were delicatessens on the Upper East Side that catered to affluent people but they were just like any delicatessen in Brooklyn, not decadent. There’s still that one on the Upper East side.

Pastrami Queen. Phenomenal.

Yeah. So, no, I don’t think it has to lead to that—but it tends to because people have strange, um ... they have lousy tastes, the rich.

The thing is, wealth doesn’t corrupt you just criminally, it also corrupts your tastes. You don’t look at things, you don’t study things, you become, you know, an idiot.

You must know that there’s a whole mythos around this book, The Dairy Restaurant.

Really?

Yeah.

Oh ...

Uh, better you don’t, but if you should ever look online there’s a lot of speculation going back a decade, like fans of yours having a discussion in 2009 about when it’s finally going to come out, or whether it ever would.

Oh, why it took so long. That’s ’cause I didn’t think there was enough information to say this is the best I could do. It started before the internet. Some of the interviews go back to the 1980s. I was just talking to people, not for a book necessarily, it was just an interest.

Do you remember the first people you interviewed?

There was a big one with the Gefen’s, they had a dairy restaurant on Seventh Avenue. I interviewed other people that had nothing to do with dairy. I interviewed people because, actually, I was just interested in Yiddish culture.

The thing is, I kept thinking about it … this is the thing I think I explain on the last few pages of this book: this endless ruminative approach to making a book like this means it’s not a concise work of art. It’s like when rumination overtakes any practical reason.

Like if somebody says to you, why are we sitting at this table with these plastic chairs [Katchor gestures to the table and to the chairs we are sitting on] and to explain that they go back to the Garden of Eden, you know, you’re into this world of the milekhdike personality who wants to engage in this kind of endless rumination about why and what went wrong. So that approach to a book, especially when you’re doing it yourself—I didn’t hire research assistants, there are people who probably could have found things that I couldn’t find, but I wanted to just stumble upon things—it took time until I thought I had enough.

Also, after a certain period I was sort of worried that my editor might retire or give up. I don’t know, I wanted to get it done at some point.

All of your work has an historical quality but this is both more like a proper history and utterly singular.

It’s meant to read like a telephone book. People are gonna come to this and think it’s going to have the concision of a comic strip of mine. They’re going to be really unhappy because it’s not meant to be a piece of art like that. There could be some accidental moments, you know, of what you call found poetry.

It’s not a work of art.

Parts of it certainly read like a work of art. Not all of it, but parts.

That’s by accident. Parts of it should read like a directory.

Parts of it do read like a directory.

One of my favorite books is these old Yellow Pages. I have like a 1940s or ’50s Yellow Pages of Chicago. That’s it. There’s a book that’s in text and clip art. Like there’s a summary of a city and if you really read it between the lines, you have a pretty interesting picture of that city. So, a phone book when they still used handmade clip art not industrial clip art. They commissioned their own weird drawings.

You’ve spent years occupying a unique place in the comics world. What do you think about the state of comics these days?

The reason this is not a comic strip is because—except for this one thing that I saw with my own eyes and I know the spatial drama of that scene in the 72nd Street dairy—if you make up the spatial drama of a story it becomes historical fiction.

I left it in the world of verbiage, single images and verbiage. And that’s not about space, it’s about time. All writers deal with time but not space. You have to fictionalize to put this stuff in a space. You’re making it up. One image sort of says this is a projected possibility, but to move it another step in time and space would be fiction and I didn’t want it to go there. I wanted it to be a book of ideas about the subject.

But the comic is now an accepted art form, right? Well, that changes everything. We’re in the world of the academic comic strip. It’s become accepted; you can win a Pulitzer Prize, it’s taught in every university in America. Once it’s accepted and people think this is a good comic—whatever that model is, Maus, or whatever it is—then they say, “Well I’ll just do that.”

That’s the death of any art, once you think there’s a canon—well, there is one now. If you’re a really good cartoonist, you just break it. It’s the same with writing; with any art form. You can get away from it. You don’t have to buy into any of these ideas of what good writing is or what writing should do.

It seems like we’re back to the same cycle where something that has a kind of vital moment is ruined by an abundance of success and recognition.

You mean like in a single artist’s life?

Or maybe something even larger like a whole culture. Like comics. Or like American Jews had this moment that peaked somewhere in the middle of the 20th century of tremendous, vital creativity …

Some of them. Most of them didn’t. Most of them were just bakers.

Most of any group of people is bakers and bankers. But there was a vitality at a moment when a lot more Jews were butchers and bakers and dairy store owners and the aim or the ethos of that generation was to assimilate and to become good middle-class Americans. Well, they succeeded but then these parts of the culture that were sturdy and had utility seemed to go by the wayside.

People were under desperate situations to make a living and to succeed. They’re going to do things you don’t do if you’re complacent and you have a cushy job. It’s out of desperation or out of utility and all these pressures. What do they say? “Necessity is the mother of invention.”

Wealth breeds boredom, or some kind of, you know, decadence. So you could become a modernist composer and nobody will want to listen to your music. That’s one way. Or you become a terrible movie composer and write schmaltzy music because that’s the way to make a lot of money. There’s no necessity now or the necessity is so, kind of, confused and diluted.

That’s why people love primitive art, children’s art, all these things that are escapes from civilization and whatever civilization does to people. That’s why the biggest thing in the art world is still outsider art.

There’s still an art world?

I’m not in it or involved in it, but I know they have these big outsider art festivals all over the world. There’s this art by schizophrenic people, autistic people, people who have escaped certain controls and don’t worry about their editor or their audience. But those people have their own crazy ideas of what they have to do. They’re also very constrained in a way

I’m just like an amateur person trying to compile this world history. And you can do it now because it’s accessible with the internet. This stuff is around and you just have to think about it long enough and compile it and then say, well, wait a minute, what happened?

Jacob Siegel is Senior Editor of News and The Scroll, Tablet’s daily afternoon news digest, which you can subscribe to here.