Beyond Poetry

An appreciation of Laura Riding, the great Jewish modernist poet who abandoned her genius to grow oranges in Florida

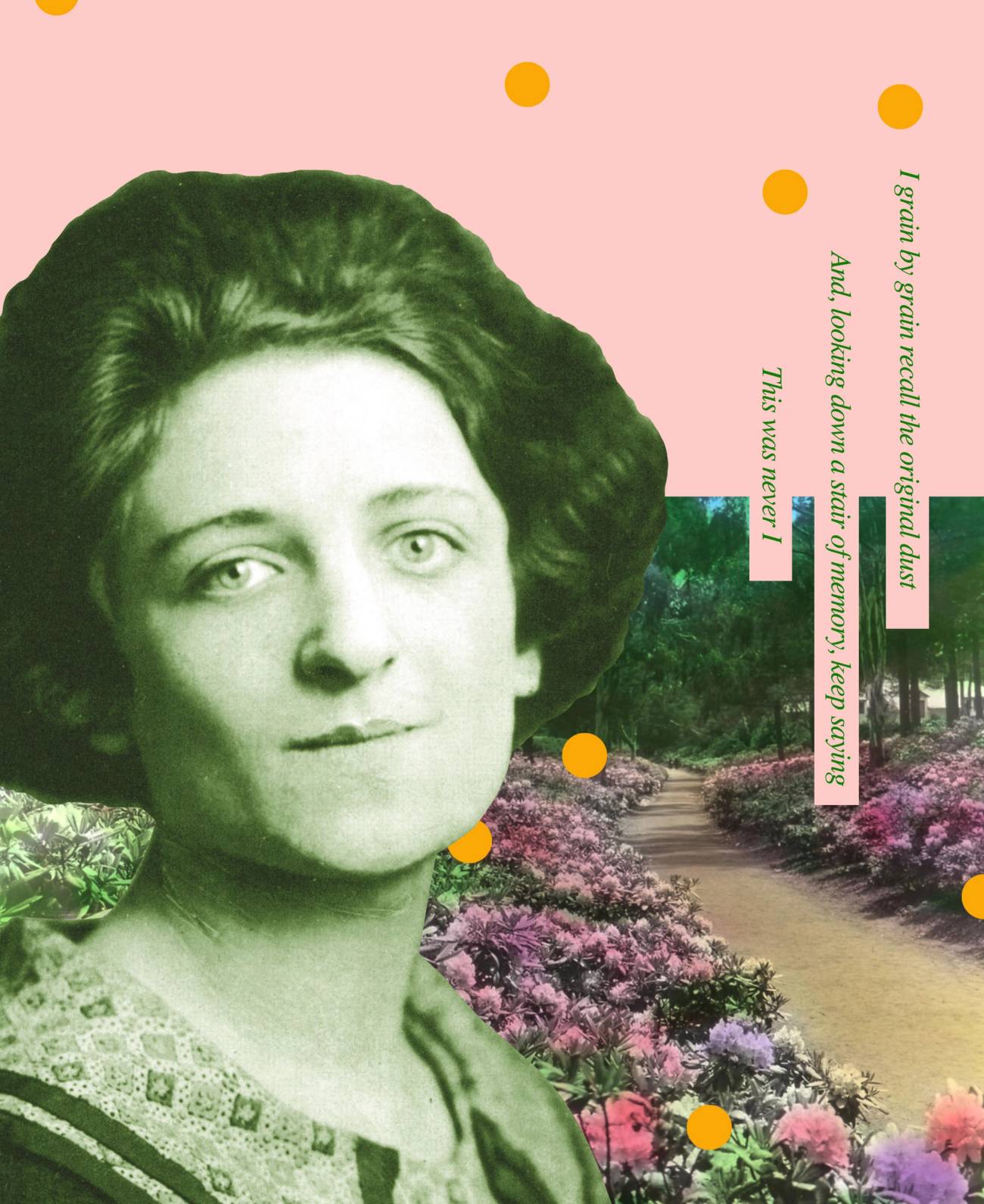

Laura Riding (1901-1990)—born Laura Reichenthal to Eastern European Jewish immigrants in New York—is perhaps the least familiar to us of the great American modernist poets who revolutionized our literature in the first half of the 20th century. Famous in her own day, in the company of Hart Crane, Gertrude Stein, and W.H. Auden, Riding renounced poetry in her early 40s to devote herself, in the obscurity of rural Florida, to citrus farming and the philosophy of language.

For decades she disappeared from the literary scene. Only toward the end of her life did she begin to answer, often irascibly, a growing correspondence from a new generation of literary scholars and admirers fascinated by her powerful, original poetry, and saddened that she had abandoned it. She could be compared, both in her ambition towards, and escape from, poetry, to Arthur Rimbaud, the French radical poet who fled his literary celebrity, and writing itself, to become a merchant in Africa. Unlike Rimbaud, however, Riding offered cogent explanations for her decision in which she denounced poetry as an inherently false medium that does not permit writers or readers to access the “truth” of human experience.

In a 1980 preface to the reedition of her collected poems, Riding traced her movement from poetry to philosophy in exalted terms. In the first half of her life, she wrote, she had been “religious in her devotion to poetry,” religious in the sense of dedicating herself to poetry as the privileged means “to think, to be, with truth.” While traditional religion struck Riding as a kind of “idealism,” oriented to what was not, in fact, there, poetry seemed, at first, to entail the “pursuit of spiritual realism,” of intimate, ordinary human experience in its most intense and clearest light, usually overshadowed in our busy, thoughtless quotidian confusion. A poem, as Riding conceived it, was not supposed to confess something about the particularities of one’s own private life, or to run with special grace and ingenuity through the established repertoire of conventionally imagined human situations. It was to reveal “on behalf of human beings generally” the fundamental but forgotten aspects of our life in the world. The desire for such revelation, she continued, is “an intention implicit in human nature,” our commonest and inmost longing.

But, Riding argued, poetry had proved a snare. Poetry was animated by our desire to better know ourselves and escape the partial, inadequate knowledge by which we dull ourselves to torpor or frenzy ourselves in buzzing, purposeless illusions of activity—it was democratic and universal. But poets, qua poets, cannot resist thinking of their particular, specialized activity as something “aristocratic,” in which exceptionally skilled verbal technicians manipulate symbols to clever effect. And indeed, poets cannot wrest their thinking free from the cliches that obscure our everyday use of language without, perhaps, becoming incomprehensible to the ordinary people whose experience poetry is supposed to illuminate.

Poetry therefore ends in an impasse. While it ought to reveal how all of us truly are, yet, insofar as it departs from conventional language and is practiced by a minority of individuals at the margins of our culture, it cannot but become a kind of shibboleth by which supposedly cultured writers distinguish themselves from others—and thus alienate themselves and language still more radically from our shared hunger for human reality.

It was perhaps more these explanations than her abandonment of poetry that has made Riding an obscure figure today. If she had simply disappeared, or tragically died, a romantic aura could have been built around her (as it was around fellow modernist genius Hart Crane). But because, with what must have seemed to those few—including Susan Sontag, who listed Riding as one of her avant-garde inspirations—faithful appreciators of the postwar years as a perversion of her poetic genius, Riding regarded poetry, hers and everyone else’s, as a “failure.”

In our own era, poetry may not seem worth the trouble to indict. We find it now, when we find it, in sadly deficient modes: the banal idiocies of “Instagram poets” like Rupi Kaur (Amanda Gorman being a superficially “political” version of this type); the bloodless tedium and glib piffle that appears in polite magazines like The New Yorker by bores like Richie Hoffmann and Noah Warren; “identity”-mongering confessions in which bits of Chinese or Spanish pathetically signify self-exoticism (pick up a copy of Poetry magazine!); the unmarketable academic projects that tenured poets assign to graduate students.

People who love poetry, knowing how bad it is now, may hardly feel the need to ask whether even the best poetry—which we are so far from getting—is something we should want. By forcing us to ask this question, by putting poetry itself at risk, Riding may, however, be the challenge we need to return purpose and vigor to this withered branch of American letters. If not, she would say, then cut it down.

Riding was a philosophical poet, for whom poetry was above all a medium for communicating ideas. Her early work, included in her first volume, The Close Chaplet (1926—recently republished by the Ugly Duckling Presse), showed her facility with conventional prosody and rhyme, but also announced that the young poet was already dissatisfied with their limitations and inherent connection to what seemed to be the exhausted topic of love. In “As Well as Any Other,” Riding addressed the muse of romantic poetry, Erato, declaring that while perfectly capable of writing about “what we know / in common secrecy”—that is, desire—Riding would rather find a rarer, more challenging subject for her own writing.

This was, on a personal level, an announcement of her break with the circle of young male poets around Vanderbilt University—the Fugitives—who were the first to bring her to the attention of the literary world. Riding’s poetry had met with the enthusiasm of members such as Robert Penn Warren and, especially, Allen Tate (with whom Riding had a brief affair) but she seems to have felt that she was being made to play the second-rate part of a young poetess to be admired (and ultimately discarded), not an intellectual equal. Riding would face a similar problem in the following decade, when she lived in a four-way romantic and domestic relationship that included the poet and novelist Robert Graves, who saw her as an archetypal embodiment of the Muse. After leaving this relationship in the most melodramatic way possible—leaping out of a window as the other three members watched in horror—Riding still haunted Graves, becoming the inspiration for his turgid and baffling celebration of the divine feminine, The White Goddess.

The poem was also a manifesto for the next stage of her career, in which Riding experimented with a new poetic form (inspired in part by her friend Gertrude Stein) organized by repetitions and unexpected combinations of words rather than by traditional structures of versification. Through these efforts, Riding used poetry as means of intellectual inquiry, asking questions about the nature of truth, the limitations of language, the relationship between the world and our knowledge of it, and the essence of the self. In her intention to capture “truth” in novel poetic form, she might be compared to Wallace Stevens, but her style had none of his archness, humor or pretentiousness. Her poems were—and over the ’30s grew more—direct, serious, and spare. Nor did her poems have the showy erudition of those of Ezra Pound or T.S. Eliot, the other American modernist poets who reinvented themselves, and American poetry, in Europe (Riding left America in 1925, returning only a decade and a half later, after she had given up poetry). Her work is difficult not because it sends the reader to the dictionary or leaves him wishing for footnotes, but because it uses apparently ordinary language in strange, surprising ways to provoke philosophical insights that place her, not just among other intellectual poets of the era but in the company of philosophical contemporaries like Ludwig Wittgenstein and Martin Heidegger.

One of the themes of Riding’s poetry is the difficult necessity of stripping away artifice, in both the language of poetry and in our inherited understandings of the world. In “Auspice of Jewels,” she begins by describing the “jeweled fascinations” by which an unnamed “They” have surrounded “us.” Riding uses jewelry as a metaphor for all the ways the products of human hands and minds help us to evade the central mystery of human being as we encounter it in the face of every other person. The original light of the human face, she suggests, has been drawn out into jewels that glitter on ears, necks and hands: “The light which was spent in jewels / has performed upon the face / a gradual eclipse.” Gladly dazzled by these twinkling, derivative lights, we are relieved not to have to look into each other’s eyes, not to confront the “too immediate” intensity that shines from the face of the other. It is now, however, time to strip off these “adornments” that had distracted and protected us from the “flagrant realness” of each other: “from this reunion of ourselves and them … Comes an astonished flash like truth.”

This “truth” that Riding sought is not the same as mere knowledge. In one of her rare poems in an autobiographical vein, Riding described her childhood education as inculcating dull conformity that falsified self and world: “I was obedient … / I learned to know the frown from the pursed smile / I won the prizes which are won / By future citizens, trained dogs …” In the classroom, the “world is broken into knowledges,” isolated facts and techniques that never seem to relate back to a meaningful whole. Instead of appearing as a unified horizon within which human beings dwell, the “world” appears as a fragmented set of unrelated bits of information that cannot orient us: “The world is many, we have learned.” The challenge of poetry is to restore the broken unity of the world by clearing language of its cliched distractions and letting us, thinking and speaking afresh, discover that we are the apertures into and from which the world, in its wholeness, ceaselessly pours.

While the “world,” for Riding, is a totality, the rightful apprehension of which is “truth,” which can be restored to us by proper use of language, our “self” is only a fragment arrogantly promoted to the rank of the whole. One of her early poems, “Incarnations,” concludes with these lines: “I grain by grain recall the original dust / And, looking down a stair of memory, keep saying: / This was never I.” The self is not a coherent, static thing inside us, she insists throughout her work. We are, rather, participants in the dance of the “world,” the ones to whom and in whom it appears and moves. Pursuing self-knowledge by trying to know ourselves in terms of biographical facts or cultivating a self-image to be sustained by the opinion of others, therefore, is a pitiful detour away from an openness towards the world in which our conventional ideas about ourselves dissolve.

Riding made this point most forcefully in a long critical essay, “Jocasta” (1928), a polemic against Wyndham Lewis’ aesthetics and politics. Lewis, Riding thought, was rightfully opposed to calls in the ’30s from political figures on the right and left for writers to subordinate the personal perspective of the artist to the needs of whichever party, movement, etc., was imagined to be the “vanguard.” Against such demands to extinguish one’s own intellect by putting it in the service of a group that spoke in the name of an imagined plenitude—the nation, the proletariat, etc.—one must, she agreed with Lewis, insist that these specters do not represent the whole, or truth, which we can approach only through the difficult work of thinking for ourselves.

But, Riding continued, Lewis—and all others who resist collectivist politics in the name of “individualism”—misunderstood the depth of the problem. He pitted the freedom of the personal self against the unfreedom of those who gave orders in the name of something greater. Riding agreed that these latter spokesmen of the collective misrepresented themselves as agents of the whole, which only can be approached in a spirit of freedom and honesty, but insisted that the “self,” is also an agent of unfreedom. The ego is a little state or party, making declarations about its values and agendas, and losing sight of the world that beckons beyond our own identity and interest.

The self as we usually understand it, she warned, is only an extension of the collectivity against which individualists like Lewis vainly struggle. It is an entirely “social self,” an accumulation of our prejudices and inherited misunderstandings; it is not that part of us that can listen to the call of “truth,” that deepest, religious yearning. The latter is a “non-social self” at work in us when we undergo, for example, literary inspiration or spiritual ecstasy. It is “outside” any “tradition and without reference to cultural line of succession.” It is what we all have in common, as human beings, and what separates us, in the moments when we apprehend it, from all products of human society, releasing us into that vulnerable, newborn openness to reality, unguarded by any previous conception of it, each of us truly is.

Riding’s dismissal of culture and tradition was of a piece with her rarely addressing her Jewishness—or anything else about what we would now call her “identity” in her writing. She refused to be published in special issues dedicated to “women writers,” and was said by her former love Allen Tate to be a kind of cosmopolitan poet who was hardly American at all (a point that, from the reactionary Catholic poet might be taken as an anti-Jewish smear). For such labels and those who needed them, Riding showed contempt. But in her poem “The Last Covenant,” Riding took on Judaism, declaring poetry the successor to religion, and herself the successor to Moses.

Riding begins with a thought that soon interrupts itself, “If ever had a covenant been sought / If ever truth had been like night sat up with,” which, by being broken off, suggests that there has never been a proper “covenant,” that the one between God and Israel was in some way false. The second line implies that the defect of the old pseudo-covenant was that it was not founded on a desire for truth, which, if sought, would lead us to lie awake wondering and doubting—not sleeping securely in the promises of faith. After a stanza, Riding resumes her original thought, declaring now openly, “There were never covenants.” What we had were only dodges, by which people accepted semblances of truth as a relief from the work of uncertainty, and celebrated themselves “in the wooden name of God.” But, the poem interrupts itself again, what about “those infatuated ordinances / Scratched on the stubborn tablets of persuasion?” These were only, Riding counters, “thoughts left unthought … reverence to a ghost-king.”

Having dismissed traditional religion, the Ten Commandments, Moses, and God, Riding foretells a new covenant. “For a man is a long, late adventure,” she wrote, who will at last know to seek pure truth rather than such proxies as God and tradition. Doing so will mean abandoning one’s commitments and identities, wandering just as the Jews did in the desert. It will also mean recognizing that what one had taken for granted as knowledge of the world and self was as temporary, and indeed as much a “trial,” as that wandering: “You shall leave those places / Each a camp raised in the shifting wilderness /… You shall reach this place.”

Where Riding arrived was the end of poetry, which is a place where perhaps few will follow her. Or perhaps, in our era when poetry is merely an unpopular genre of literature rather than anyone’s candidate for the best approach to truth, we have already, without sharing her bold thinking, followed her path. Retracing our steps back to Riding’s original sense of poetry as a religious vocation, and then her abandonment of it as yet another false faith—like monotheism and politics—is an opportunity to rediscover one of the greatest of modern Jewish writers (great, precisely, in her wrestling with those adjectives) and to reawaken the “intention implicit in human nature” that drives us to, and perhaps beyond, poetry.

Blake Smith, a contributing writer at Tablet, lives in Chicago.