Primo Levi once wrote that “a dozen rivers can’t wash away the Yiddish accent.” What Levi perhaps did not anticipate was that, for some American Jews, the very sound of Yiddish would become a proud badge of cultural identity, not a shameful (and dangerous) marker. If ever there was a true advocate of the merits and delights of the Yiddish accent, it was clarinetist, stand-up comic, and bandleader Mickey Katz.

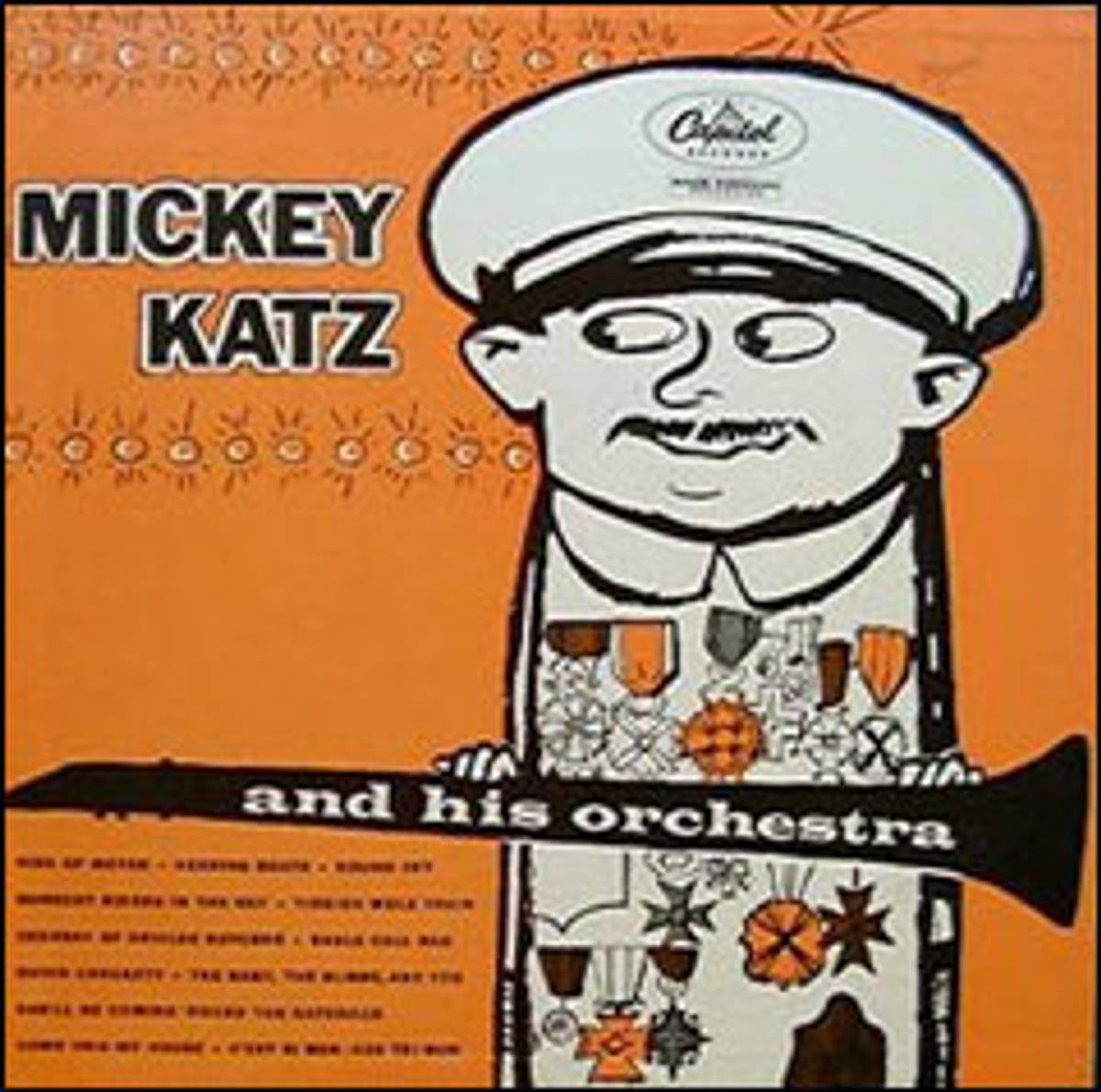

By the 1960s, Katz’s manic cultural energy could no longer compete with the growing power of nostalgia, typified by Fiddler on the Roof and The Joys of Yiddish, or the hard-edged humor pioneered by Mort Sahl and Lenny Bruce, for whom Jewishness was only a starting point for a larger assault on American culture and politics. Since then, Katz has occasionally returned from obscurity in tributes by his son Joel Grey (including an NPR Hanukkah special a few years ago that I worked on), granddaughter Jennifer Grey, and Don Byron, an African-American jazz clarinetist who eloquently saluted Katz’s musical iconoclasm and screwball humor in a much-acclaimed 1992 recording. For the most part, however, Mickey Katz has been dismissed by Yiddish culture activists and scholars alike as a novelty act, a self-hating Jew, and a colorful but irrelevant historical footnote—until now. As many younger artists and academics troll the Jewish-American past in search of new ethnic cultural heroes, Mickey Katz has found a new champion and advocate in the form of a energetic music critic and English professor named Josh Kun.

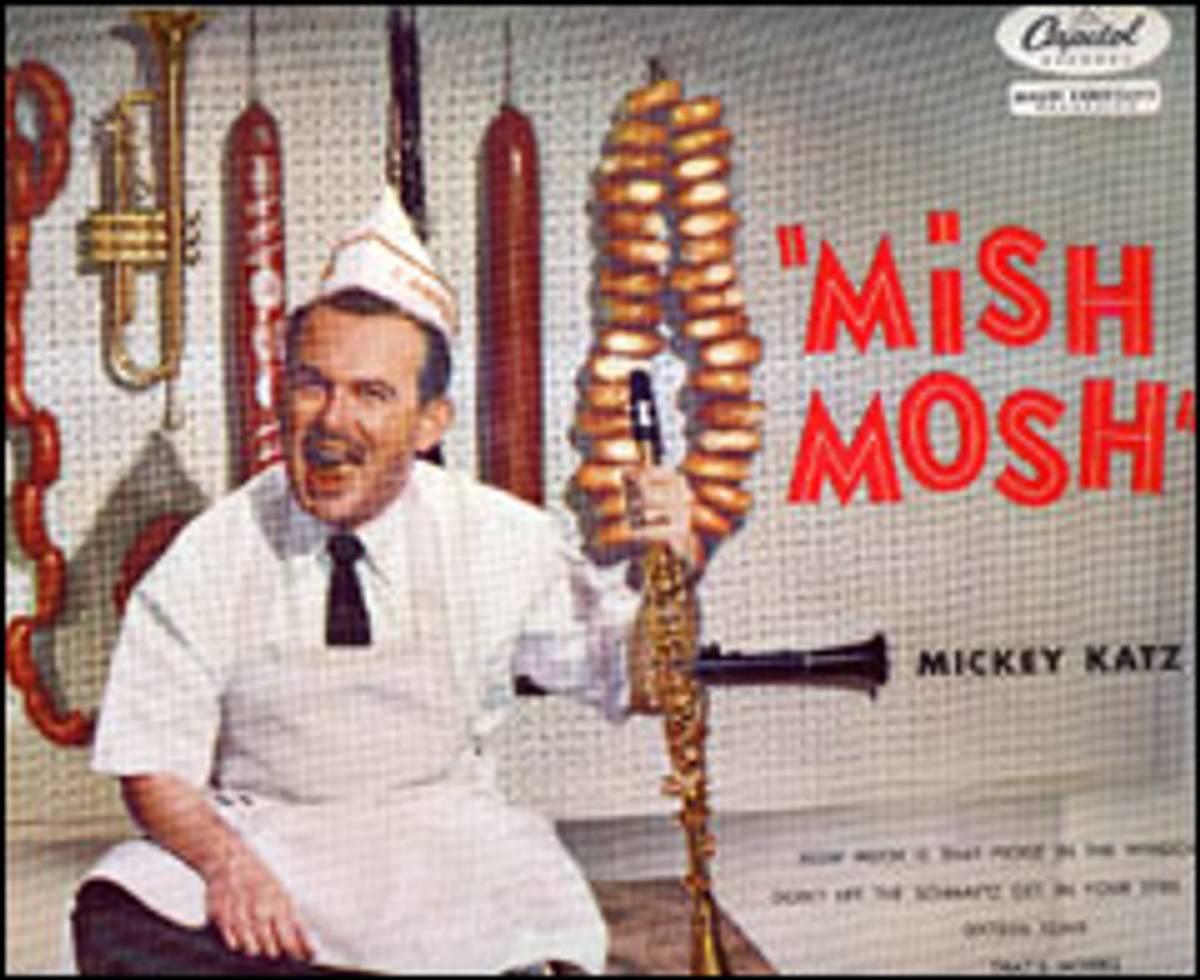

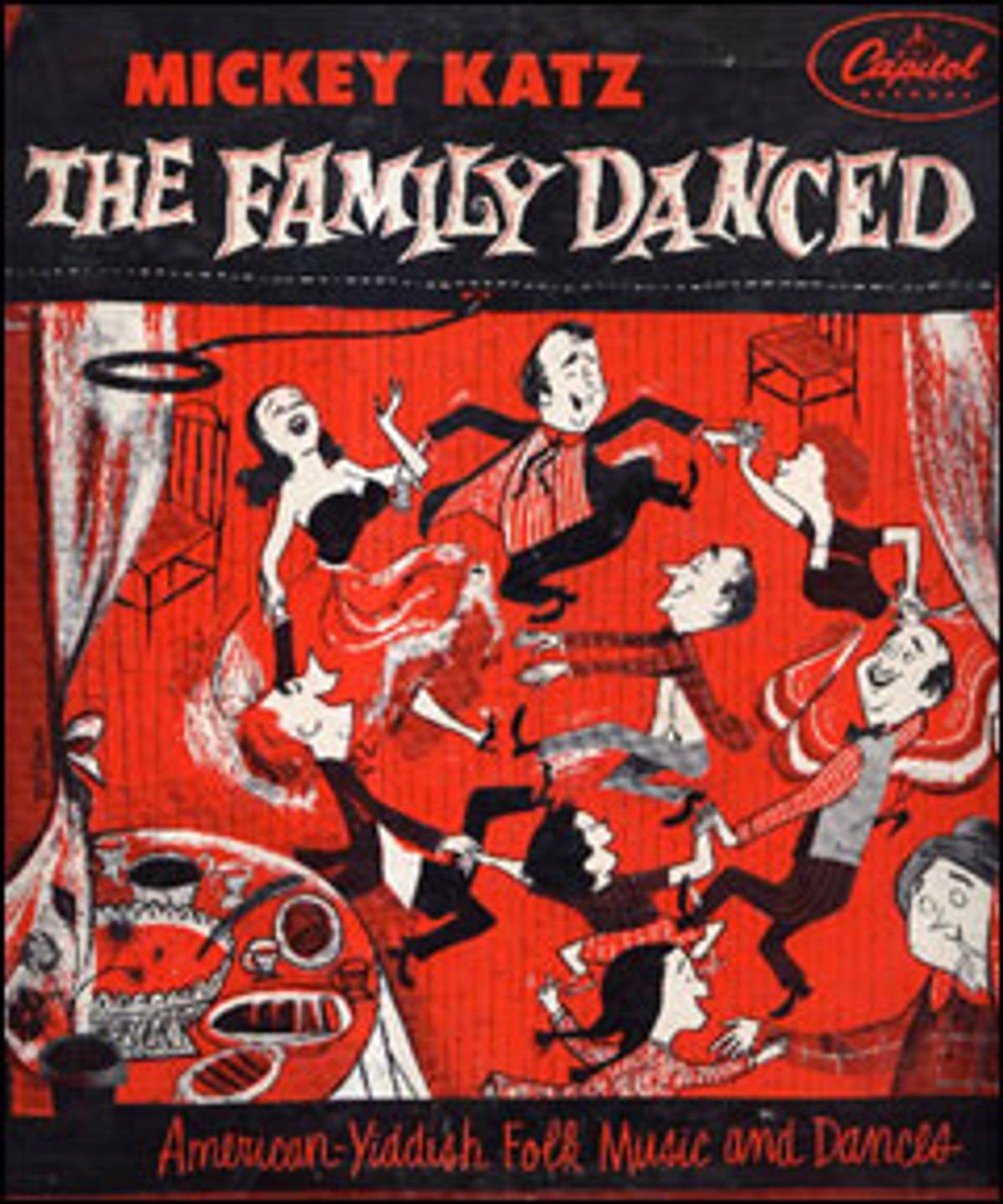

As these names suggest, Kun’s Audiotopia is very much a product of multiculturalism, especially in its keen focus on the central role of African-American and Latino artists and identities in the American cultural landscape. And yet right smack dab in the middle of this pantheon of multicultural icons we find Mickey Katz. For Kun, Katz is the poster boy for a ribald, robust Jewish ethnicity—or, as Kun puts it, an “unabashed ‘Yidditude.’” Katz’s Yiddish-accented parodies seriously challenged the melting pot ideal of Americanization. To Kun, Katz’s “unassimilated notes of Jewishness” constitute a defiant rejection of postwar attempts at Jewish assimilation.

Clearly Katz’s jubilant, in-your-face Yiddishkayt was an implicit critique of an era of unprecedented name-changes and nose jobs. But does that make him a cultural revolutionary? For all of his bold, brash, and loud Jewish identity, it’s still difficult to think of Katz as a cultural visionary or political radical in the same way as African-American musicians such as Kirk or Tupac. In a book that celebrates the edgy creativity of jazz, blues, mambo, gangsta rap, and rock en español as multicultural responses to mainstream American pop music, Mickey Katz’s comic klezmer seems strangely unhip and awkward. But this very discomfort is what Kun celebrates. For him, Katz’s Yinglish comedy is not simply an unabashed affirmation of Jewishness but a challenge to all American identities from the vantage point of a Jew who is too white for the multicultural rainbow and yet too Jewish for white America.

That night the shofar was blown and, as usual, I marveled at the triumph and violence of its sound—a blast of human air sprayed through the horn of a dead ram. When you hear the blowing of the shofar, there is no way to feel at ease with it. It is always an affront, always uncomfortable, always aggressive in its volume and its frequency, in the sheer force of its howling, breathy noise….

Inspired by the rabbi’s description of the shofar as “‘a stranger among sounds,’” Kun uses the incident to frame his book’s fundamental challenge to all American cultural identities:

The shofar is certainly a stranger among sounds, but it also makes strangers out of all who hear it. We are strangers among its sounds, its blast of bleating air confronting all of us in that room equally, forcing all of us to confront our identities as listeners…. This idea of being a stranger among sounds immediately seemed a fitting way to understand how identity and listening work…. Popular music has always been my refuge because it is the refuge of strangers, because in the world of popular music, we are all strangers among sounds made by others.

If the shofar can help explain the history of Mexican-American rock and gangsta rap, what does that mean for the fate of Jewish culture today? Can younger Jewish-American artists and musicians reclaim the Yiddish accent that Kun celebrates? Or have the rivers of American pop music washed it away for good? Josh Kun does not answer these questions in his book. Nor does he need to, since his book’s primary focus is American culture and identity. For all of the centrality of Jewish themes in this book, they are only part of the cultural mosaic that Kun hears in America’s music. This means that he leaves unopened the question of what Katz’s audience would be, or could be, today. Listening to Mickey Katz is only funny, after all, if you know enough Yiddish to catch the jokes.

James Loeffler is the author of The Most Musical Nation: Jews and Culture in the Late Russian Empire and co-editor of The Idelsohn Project.