Big Thief Has No Balls

The band’s cancellation of its Tel Aviv shows, despite having a member who currently lives there, is the latest mob-driven act of meaningless cowardice

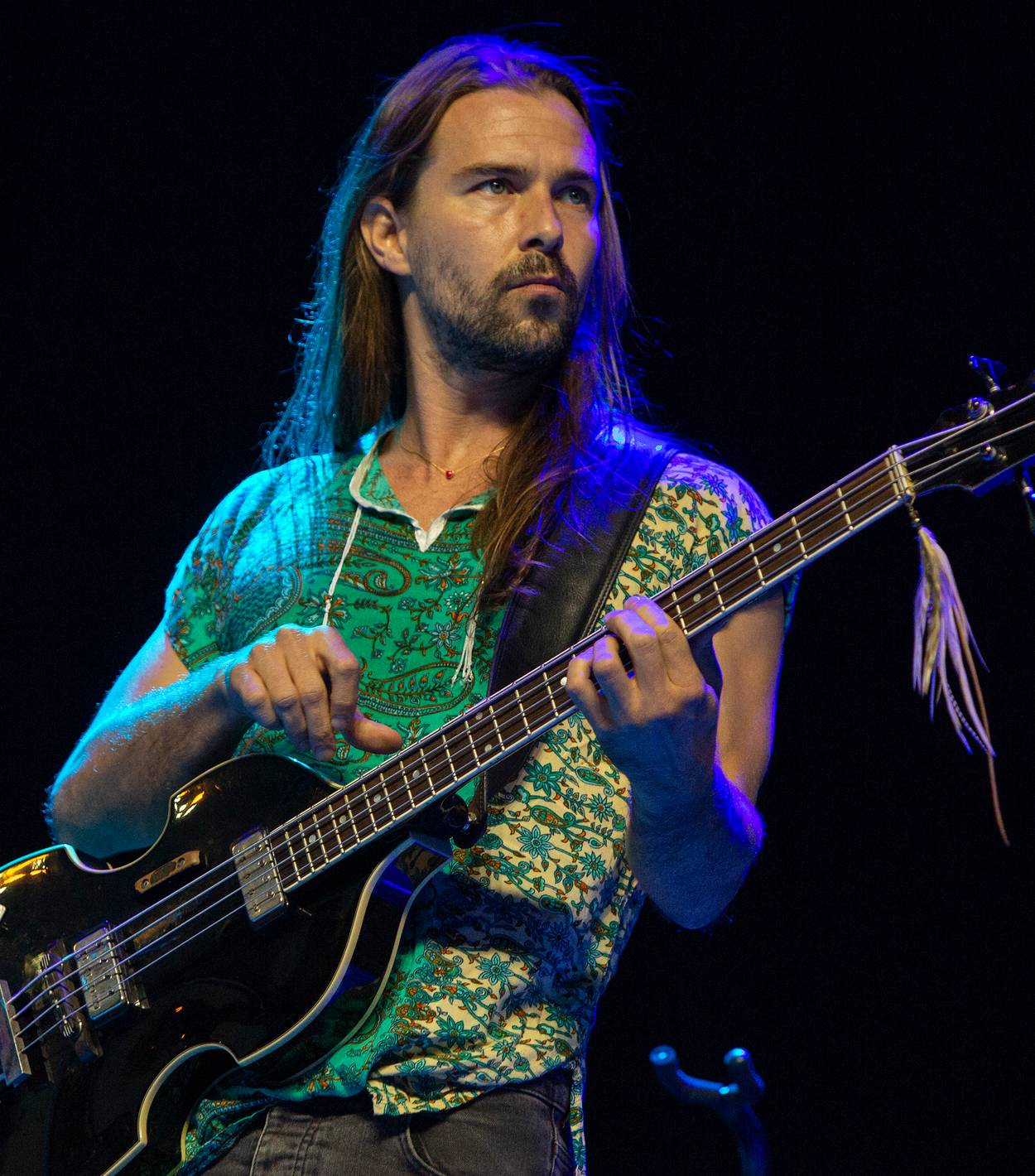

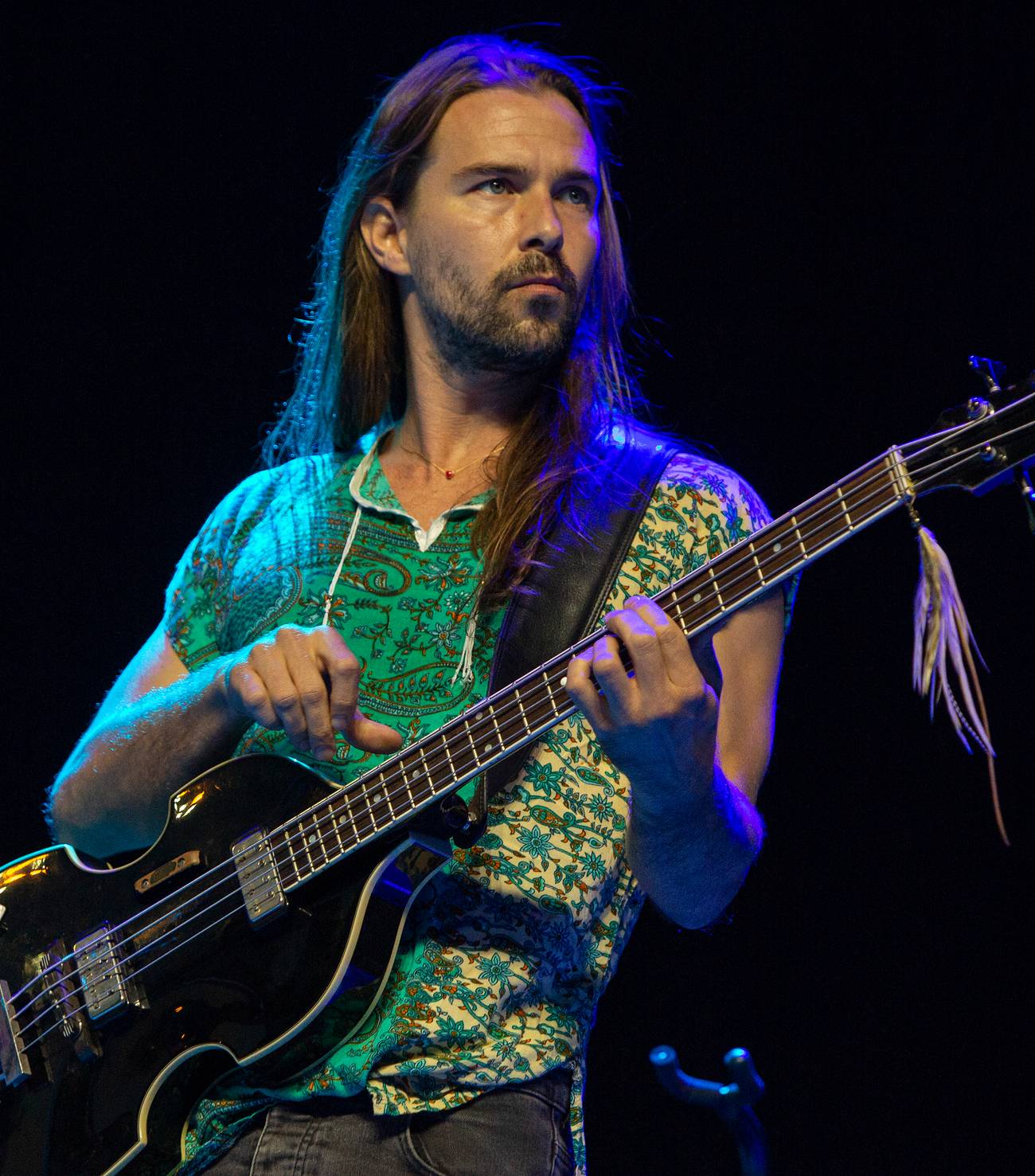

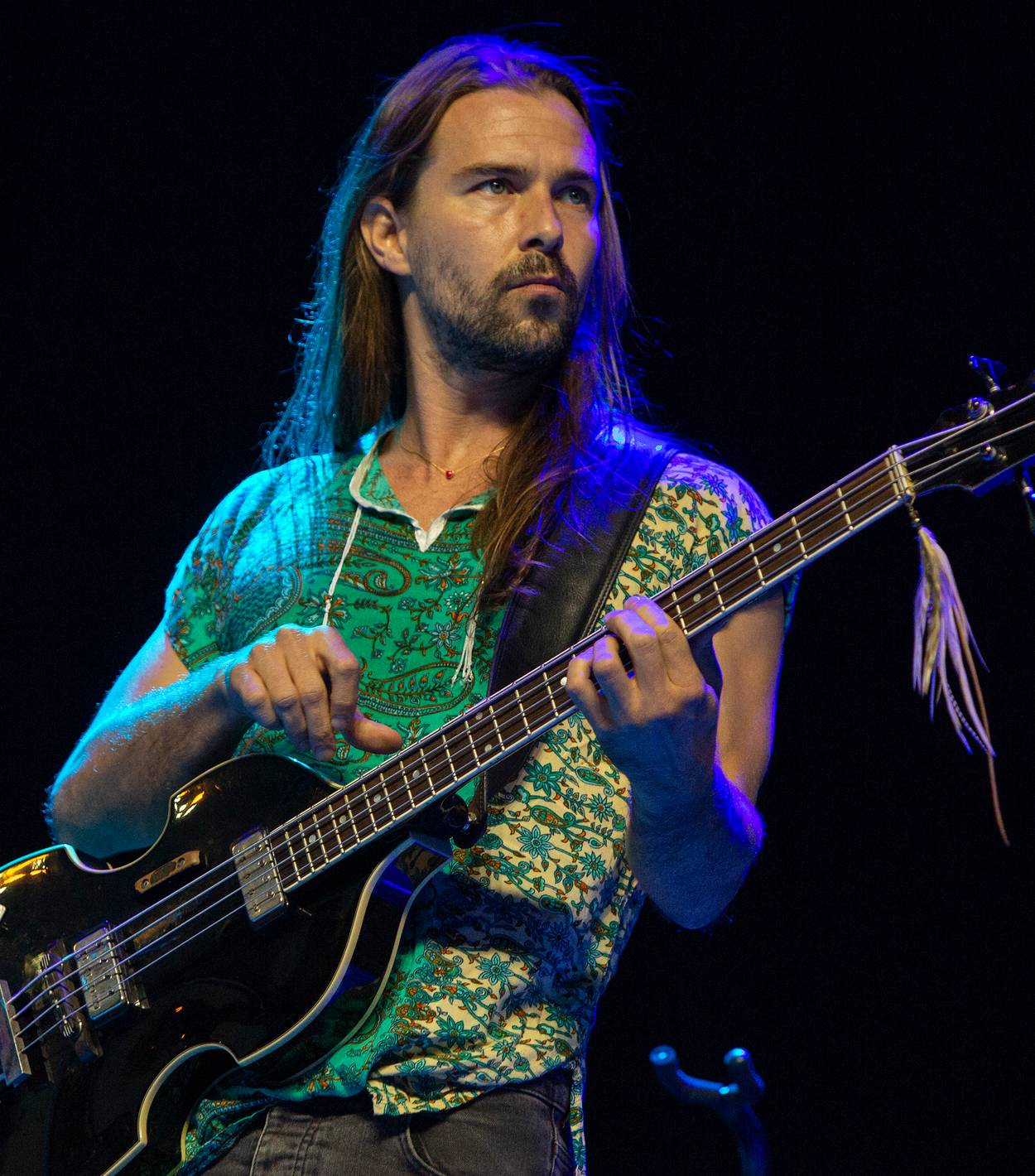

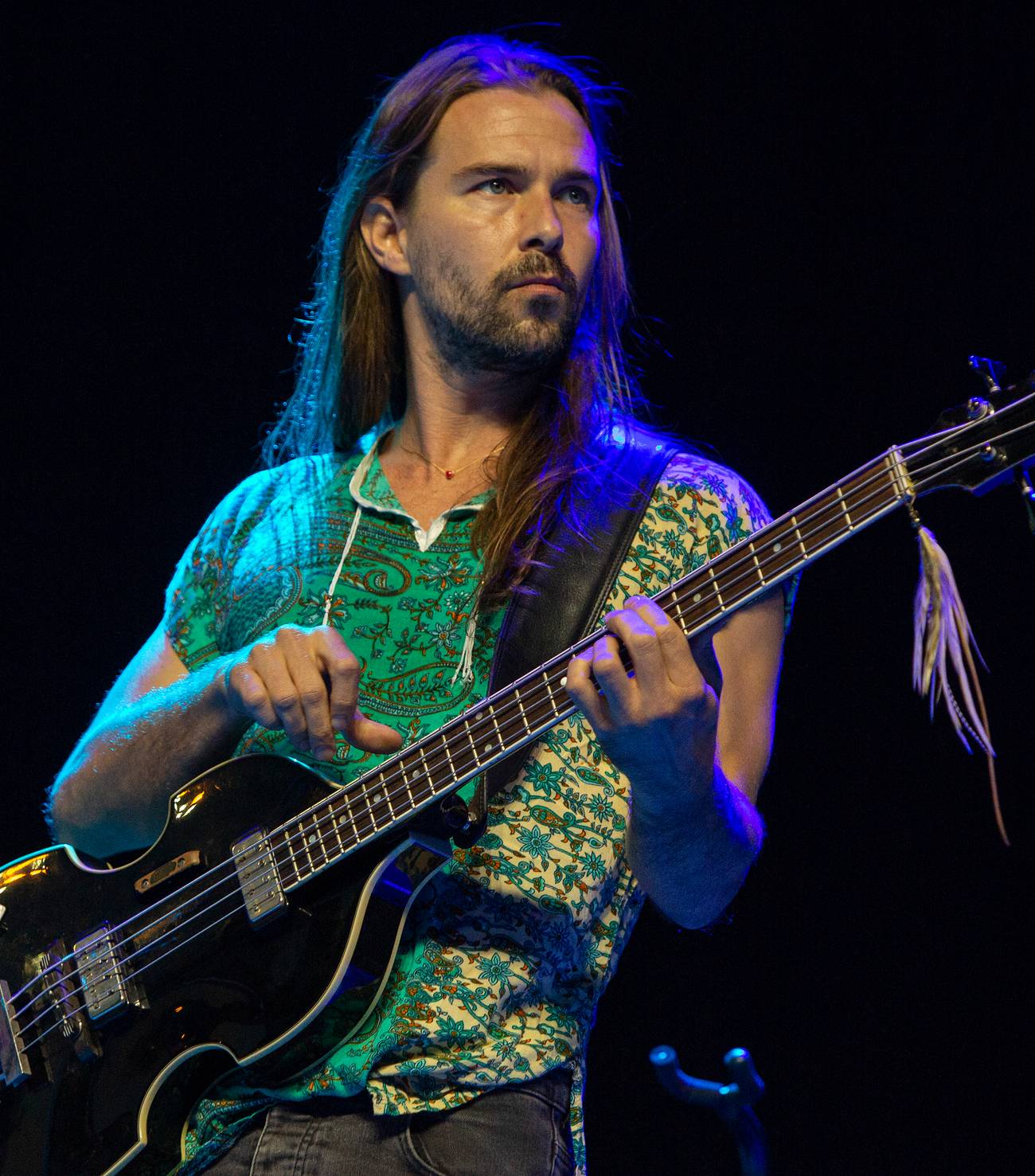

The folk-rock band Big Thief’s cancellation of two upcoming shows in Tel Aviv ranks as one of the more facially dishonest BDS-related episodes of recent years. The Brooklyn-based group was eager to play in Israel, where they’d already performed in 2017, and had a well-developed rationale for doing so. Max Oleartchik, the band’s bassist, was “born, raised, and currently lives” in Tel Aviv, according to the statement the band released announcing that the shows were off. Just days earlier, Big Thief explained it was playing in Israel because “it is important for us to share our homes, families, and friends with each other … It is foundational.”

Barby’s, the Tel Aviv club where the cultishly admired quartet was due to play on July 6th and 7th, noted in a scathing Instagram post that the band had directly reached out to them about performing there, which is the exact opposite of how things usually work in the live music industry. The concerts weren’t an easy payday brokered through a manager or a booking agent. True to the spirit of their alluringly moody catalogue, Big Thief had an emotional investment in playing in Israel, but then let itself get intimidated into pretending otherwise, making their submission to BDS dogma a simpering act of compliance with a mob the group had no practical obligation to satisfy. Big Thief’s Dragon New Warm Mountain I Believe in You is one of the best-reviewed records of the year, and they sell out almost every room they play these days. Yet their announcement—glaringly wooden for a band that trades in earnest feeling—reads like a frenzied plea for mercy, written not by the sharpest songwriters of their generation but by people for whom fear has stymied any basic use of English. “As a band, we consider each other family, forever reaching to understand each other,” the statement closes, continuing in equally incoherent fashion as it obsequiously thanks the group’s tormentors: “In your responses to our actions, you have helped us to realize that we were in avoidance of entering this discussion about Max’s home in a more thoughtful way.”

The incident suggests the incompatibility of BDS with even the most liberal-leaning edge of Israeli society. Max Oleartchik’s father is Alon Olearchick, a principal member of Kaveret, the 1970s power-pop group that competed in Eurovision and that is by some accounts the most commercially successful Israeli band of all time—its song “Yo Ya”, a Jewish summer camp mainstay, is just as catchy as it was 50 years ago. Alon’s father was a Polish composer of popular songs who weathered the entirety of World War II in the Soviet Union before becoming a dramatic director for the Polish army under the country’s new communist government. Perhaps recognizing what life as a propagandist for an antisemitic regime would be like, he moved to Israel in 1957 with his Catholic wife and Warsaw-born 7-year-old child, Alexi, the future Alon.

As a prominent artist with such a tangled and confessionally mixed background, it is perhaps unsurprising that Alon Oleartchik, who has had an illustrious post-Kaveret career as a songwriter and composer of Israeli film scores, became a plaintiff in an unsuccessful attempt in the 2000’s to allow Israelis to opt out of the “Jewish” nationality category on personal documents issued by their government, including identity cards. The plaintiffs were suing for the right to list themselves simply as “Israeli”—a label which, interestingly enough, does not exist within the government’s classificatory systems. Whether this case was a challenge to the state’s Jewish character or a well-meaning bid to expand the scope of citizenship within an ever-fluid national project is an interesting and complicated question. Regardless, the point is that Alon certainly can’t be tagged as a mindless nationalist.

This is why it is notable that the elder Oleartchik apparently focused on the coercive tactics of the BDS campaign, rather than its potential to achieve peace or justice, when discussing the canceled shows with Kan, Israel’s public broadcaster. “They received thousands of threats… the reaction they received for [announcing] a performance in Israel was awful and terrible,” Alon said, according to the Times of Israel. “They were crushed by it.” Max, meanwhile, “was also crushed by this. He really wanted it to happen.”

But Big Thief effectively sold out its Israeli member, condemning the country he lives in as simply too evil for them to bless with their presence. If the band really had the convictions they now claim to hold, and the courage to back them up, they would eject Max Oeartchik entirely—or else they should clarify what makes him different from the rest of his fellow Tel Avivians, the Jews and Arabs who the band has deemed to be so awful. Instead, the band has declared that Israelis are acceptable on an individual level–so long as they’re the right ones and as long as they’re in the band Big Thief–but loathsome in their collectivity.

Alon Oleartchik, despite or even because of his belief that Israel should move towards a more liberal sense of national identity, seems to have recognized the show cancellations as an act of cowardly exclusion. Big Thief’s announcement is yet another sign that many of today’s artists are conformists who fear and distrust even their deepest selves. In Big Thief’s case, they’re people who would rather satisfy a rabble of internet activists than behave decently towards a friend and colleague, a supposedly valued member of their “family” who happens to be a citizen and resident of the only majority-Jewish country in the entire world.

Armin Rosen is a staff writer for Tablet Magazine.