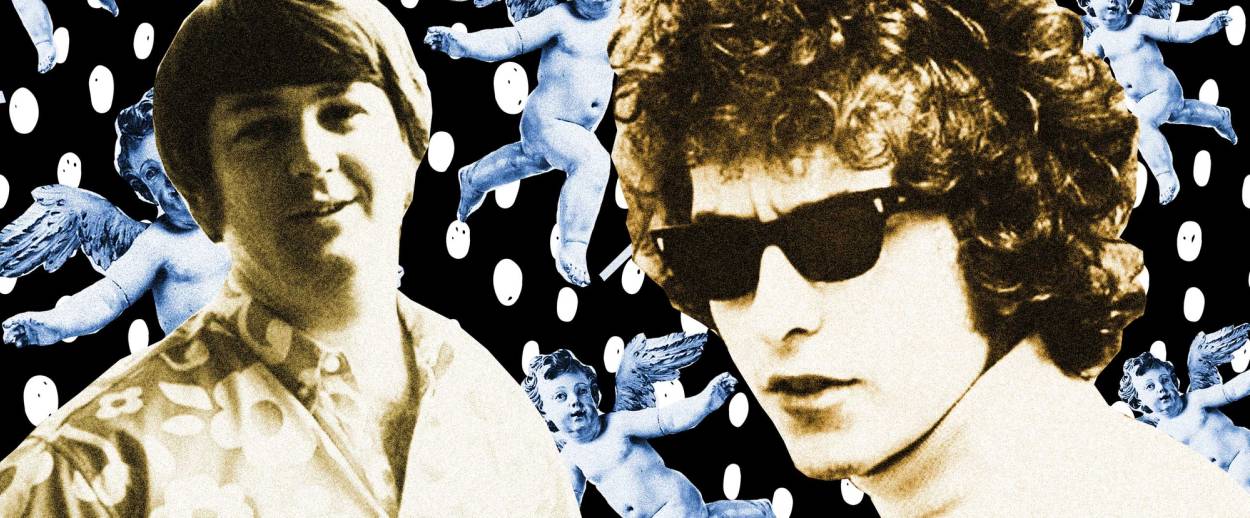

Fifty Years Ago This Week, Two of Rock’s Greatest Albums Were Released on the Same Day

‘Blonde on Blonde’ and ‘Pet Sounds’ are American gospel

On Nov. 30, 1965, Bob Dylan walked into a studio in New York City to continue recording an album, his third that year. He had begun working on it two months earlier, but distractions abounded, including marrying his girlfriend, Sara Lownds, and divorcing his bandleader, Levon Helm, who was tired of playing second snare to a capricious 24-year-old who was just as gnomic instructing his musicians as he was in his inscrutable lyrics. None of these entanglements were evident, however, when Dylan entered the studio that winter day. He had written a masterpiece, he told anyone who’d listen; it was called “Freeze Out,” and he needed to record it right away.

“Stop, that’s not the sound, that’s not it,” Dylan muttered after a few false starts, the whole account captured by historian Sean Wilentz in his book Bob Dylan in America. “I can’t… ‘ats not… bauoom…it’s, it’s more of a bauoom, bauoom… it’snota, it’snota, it’s not hard rock.” A few more duds later, the band seemed to be inching closer to the master’s vision. Bobby Gregg unleashed something that sounded like a slowed-down Motown drum fill, while Robbie Robertson played sharply, cutting Dylan’s harmonica intro with short icepick-like stabs of his electric guitar. Then, the first line: “Ain’t it just like the night/ To play tricks when you’re trying to be quiet?”

Like the photograph of Dylan that would eventually appear on the new album’s cover—Bob, blurry, wearing a scarf, squinting at the camera like he was trying to decide if anything he was seeing was really real—the song teetered on the brink of the absurd. It wasn’t just the usual Dylan imagery, rich and strange and unexpectedly funny, like those sneezy jelly-faced women who can’t find their knees. It was as if, as music critic Wilfrid Mellers observed, time and consciousness themselves were melting, ordinary people were growing mythological and vice versa, and every bit of certainty just went floating in space, bobbing up and down on that throbbing bass line laid down by the great Joe South.

It was a departure for Dylan, literally as well as figuratively: Sick of the confines of his West Village fiefdom and the hipster aura that illuminated his every step in New York, he decamped to Nashville, where he finished recording “Freeze Out.” It was now called “Visions of Johanna”; together with 13 other songs, it was released, on May 16, 1966, on a double album titled Blonde on Blonde.

As always with Dylan, the exegesis began right away. What was the Voice of His Generation trying to say? Too many things to parse right away, but one was clear above all: Dylan was saying goodbye. “I don’t consider myself outside of anything,” he told an interviewer when the album finally came out, “I just consider myself not around.” His loneliness, his heartbreak are there in every note and every wail. Dylan later praised the album, famously, for “that thin, that wild mercury sound,” but Al Kooper, as perceptive as any of Dylan’s interpreters, was closer to the mark. “Nobody,” he said, “has ever captured the sound of 3 a.m. better than that album. Nobody, not even Sinatra, gets it that good.”

A few days after Dylan first began working on the song, and a few thousand miles to the west, an ad man named Tony Asher answered the telephone. The man on the other end of the line said he was Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys, reminded Asher that they had met a few days earlier in a recording studio where Wilson was trying out some new songs and Asher was recording voice-overs for a commercial, and asked Asher if he’d like to come over and collaborate on some new stuff Wilson was kicking around in his head. Asher laughed it off and tried to guess which of his friends was goofing on him by pretending to be the one man in pop music he admired most, but the voice was unmistakable: It was Wilson, his invitation sincere.

Asher took an indefinite leave of absence from the ad game and went to meet his hero. At first, Wilson played tapes of songs he’d recorded but whose lyrics weren’t to his liking—“Sloop John B,” “You Still Believe in Me,” all almost there but not yet, like vessels waiting for that final gust of wind to push them to shore. Then came the feelings: Wilson would play Asher a record, note its emotional frequency, and say, “Oh, you know, here’s a feel I love.” Or, the lyricist later recalled, he’d talk of subjects that interested him, like the loss of innocence or the souring of childhood into maturity, speaking in the most amorphous terms imaginable. It was as if, as Wilson put it a while later, he was imagining a teenager’s symphony to God, and he needed Asher to pen his gospel.

The result was autobiographical, but it wasn’t Wilson’s autobiography or Asher’s but rather a collective autobiography of everything we all feel when we wake up in the morning and are moved by the mystery of how impossible it is, how inevitable, and how stupidly joyful just to try and reach out to another human being. The eventual album Asher and Wilson made together, as one critic wrote a few years after its release, was great “not only because of the lush, dramatic arrangements”—Wilson, obsessed with Phil Spector, had famously ushered a phalanx of musicians into the studio to build his own Wall of Sound—“but because the strangest of the brothers Wilson has his psyche on the pulse of universal subjectivity.”

Like Dylan, Wilson too was not around: Shortly after he was done recording, he checked himself into a psychiatric hospital and, in many ways, didn’t check out for decades, burdened by his tenuous command of his own mind, his appetite for hallucinogens, and his growing inability to turn the sounds he was hearing in his head into music others could hear and feel as well. But the album he made with Asher was a supernova whose light continues to shine decades later. It was called Pet Sounds, and, like Blonde on Blonde, it was released on May 16, 1966—50 years ago this week.

For all their differences, both albums are two strands in the same conversation, the one that turned American popular music, for one fleeting moment of one year in the middle 1960s, into a religious movement geared toward capturing all of the spiritual thirsts once slaked in churches and synagogues and other traditional settings and serving them a tall cup of transcendence through bass, guitar, and drums. Like never before or since, rock musicians attempted to hammer away the barriers that stood between them and the Eternal, pushing form as far as it would go and trying, as the Lothario messiah of the moment, Jim Morrison, so neatly put it, to break on through to the other side. Jimi Hendrix, for example, was condensing the entire blues scale into one wicked chord, while Joplin reduced all human expression to the rubble of one primal growl. Wilson needed an orchestra’s worth of instruments to capture his feelings, while John Lennon instructed his studio engineer to route his voice track from the recording console into the studio’s speaker so as to make the Beatle sound “like the Dalai Lama and thousands of Tibetan monks chanting on a mountain top.” Rocky Erickson, releasing his first album with the 13th Floor Elevators, sounded like a feral cat scratching at his neglectful owner, while Dylan, on Blonde on Blonde, sounded like he’d given up on humanity and was reserving his best chants for some higher authority. When Lennon, chatting with a reporter for the Evening Standard in March, predicted that Christianity would vanish and sink because he and his lads were more popular than Jesus, he was decried as a flippant rock star. He wasn’t: Rock ’n’ roll, in 1966, was the new religion, and it reached its peak ecstasy that day in May when its two most shattering testaments to music’s ability to move us were released. You can almost imagine St. Augustine—who famously wrote of hearing a hymn in a church and feeling transformed by the truth seeping into his heart—going to a record store, returning home with the day’s bounty, listening to Dylan and Wilson, and reinventing the notion of Grace.

Rock stars weren’t the only ones to notice that there was something happening here. Theologians did, too. “Because we live through time,” wrote American scholar Don E. Saliers, “music is perhaps our most natural medium for coming to terms with time, and attending to the transcendent elements in making sense of our temporality. Our lives, like music, have pitch, tempo, tone, release, dissonance, harmonic convergence, as we move through times of grief, delight, hope, anger, and joy. In short, music has this deep affinity to our spiritual temperament and desire.” How else to understand lines like Dylan’s “Inside the museums, infinity goes up on trial/ Voices echo this is what salvation must be like after a while?” How better to approach Wilson’s “Wouldn’t It Be Nice,” a writhing and restless prayer for an adulthood of rest and bliss that is done with all the judgments of adolescent angst? These are serious questions, and in America, for one day at least, 50 years ago, they were addressed by the people best equipped to answer them, musicians, on the best format humanity has ever crafted to address matters of love and loss and yearning, the LP.

It was all downhill from there. Music soon suffered devastations that were every bit as theological as they were artistic when its prophets discovered that there is no other side for a human to break on through to, and that a mortal’s quest for transcendence may just as easily end with an overdose in a bathtub at the age of 27. Morrison, Joplin, Hendrix all went that way. Wilson locked himself up with heroin and vodka in the chauffeur’s quarters of his estate, recording mad counterpoints on tapes and shunning all human company. Dylan crashed his Triumph Tiger 100, recovered, convened his band in a basement to record some of the greatest music no one would hear for five decades, and then put on a white-face mask and went on tour, dressing up his solemn hymns as funhouse ditties to the chagrin of many of his fans. All those who had prayed earnestly with their music in 1966 were soon dead or hiding in plain sight.

Which, at least for those of us who weren’t yet alive or weren’t yet adults in 1966, shouldn’t necessarily sound as a dirge. Listening to Blonde on Blonde or Pet Sounds today is like strolling through the ruins of a formerly great civilization: never without a tinge of regret for seeing the great pursuits of our ancestors reduced to polite plaques commemorating dates and names half-forgotten, but also never without a spark of hope that great things can be built, done, and recorded once again. At this moment in our collective history, with America’s greatness but a memory fading into a grotesque slogan, we need all the reminders we can get that we are, at core, a nation of religious pulsations and that when allowed an open heart and a few breaths of inconvenient candor we can still make the most beautiful music in the world.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.