The Book of Ruth

Ruth R. Wisse’s new memoir is sharp, examined, and a more urgent read than ever

Like the poet John Masefield, I also suffer from “sea fever” and so down I went to the “seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky.” I needed no “tall ship,” only a room on the beach with a terrace—and all the time in the world to read Ruth R. Wisse’s new book, Free as a Jew: A Personal Memoir of National Self-Liberation.

Reader: I could not put it down. I still chose to read it slowly, to savor it, take it all in. I must have underlined at least a quarter of the book. Wisse commands an aerial view of Jewish history, bringing it to bear on Israeli politics and on the demonization of the only Jewish state. She continues to issue her clarion call about the plague of “political correctness” that threatens to devour the entire Western enterprise.

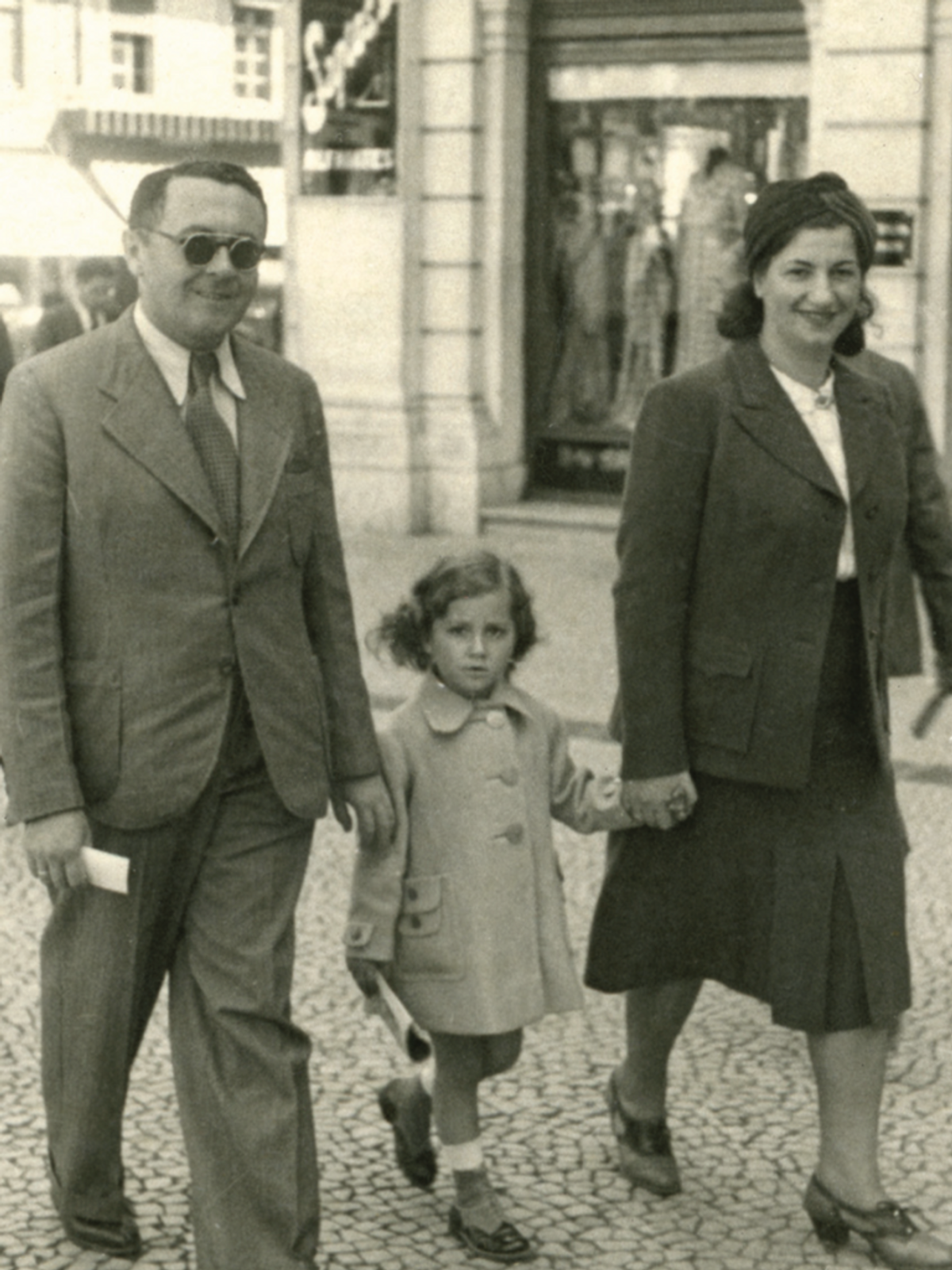

Free as a Jew is an “intellectual memoir,” but it is also a family history replete with charming photos; a story of European Jews before, during, and after the Holocaust; and a warm introduction to Yiddish literature, and to many of the major Yiddish writers whom Wisse and her parents knew, hosted, and supported in Montreal, where they lived after fleeing Romania. Wisse introduces us to many of these writers: Sholem Asch, Sholem Aleichem, Itzik Manger, Mendele Mokher Sforim, Abraham Sutzkever, and Chaim Grade, as well as to Bashevis Singer, Saul Bellow, Leonard Cohen, Hillel Halkin, Yehuda Amichai, Irving Howe, and Norman Podhoretz.

For Wisse, Yiddish is not a social justice enterprise, nor is it mainly associated with “progressivism.” Rather, it is a rich language, “associated with the actual Yiddish-speaking communities, which remained what they had always been: outposts of Jewish separatism, consisting mainly of religiously observant Jews living culturally apart from the surrounding population.” Yiddish—the language, the culture, the works—is not meant to be politicized.

Free as a Jew is also a story about Ruth’s love affair with Israel, and about Montreal’s Jews (told through the lens of Ruth’s long career, both at McGill and in publishing, long before she accepted a position at Harvard).

But this work is primarily a quintessential history of ideas, and about the law of unintended intellectual consequences. Wisse now questions her founding Jewish studies, just as I’ve questioned my founding of women’s studies because all identity-based academic studies have become weaponized in the war against Western civilization, which has also come to mean a war against America and Israel.

With that said, at first glance the esteemed author and I could not be more dissimilar. She is the daughter of privilege, with grandparents who founded a Yiddish publishing house in Vilna and parents who ran literary and political salons. I am more a “daughter of earth.”

While my maternal grandparents, with whom we lived, spoke only Yiddish, it was the language of adult secrets and I was not encouraged to understand it. Ruth remained in the safe and loving bosom of her immediate and extended family circles for the rest of her life; I fled mine as soon as I could. Her family was not particularly religious; mine was.

Perhaps paradoxically, Wisse proudly became a traditional wife and mother, someone who could not understand why women would not view men as their beloved protectors. She was comfortable as the only woman in a group of powerful literary men, perhaps even preferred it that way and, with some exceptions (she supported abortion rights and the “decriminalization of homosexuality”), strongly opposed the feminist movement.

For my part, I am on record as a fabrente feminist and an all-around rebel activist—once a leftist, but always a radical feminist who pioneered the issue of violence against women and documented how women of all races, classes, ethnicities, and religions are specifically endangered and discriminated against as women.

I was also always a Zionist. I understood that Zionism was, and still is, the liberation movement of the most maligned and persecuted people on Earth, and that anti-Zionism is synonymous with racism and Jew-hatred. I “got” this long ago—I’m not one of those leftists who were finally mugged by reality. But I did not dwell upon it, or specialize in Judaism or Israel, even as I moved through the decades publishing original feminist work, teaching, and organizing.

I mention all this because as of the 21st century, Wisse and I agree on so many deeply important things.

I wish I had read her earlier books a lot sooner—it would have helped me enormously. Since I did not, I could not stand on her bountiful shoulders and had to reinvent some wheels for myself. I am thinking, specifically, of her 1992 work If I Am Not for Myself … The Liberal Betrayal of the Jews, in which she analyzes how classical liberalism became illiberal and intolerant, and how its adherents blindly and passionately embraced the Arab, Soviet, and Palestinian propaganda-of-inversion against the Jewish state. Suddenly, Palestinians became the injured and vulnerable party, the victims of Jewish colonialism and imperialism. This view has festered and worsened and may now be beyond any and all rational dialogue.

For pointing this out in 1992, Wisse was attacked in the pages of The New York Times and The Washington Post and branded a “neoconservative,” which, back in the day, was tantamount to being accused of racism, fascism, and Nazism combined. Her views were only defended in the pages of Commentary, her political-intellectual “home.”

Yet, at the time, Wisse was not only accurate. She was prophetic.

Wisse is also tough-minded about the misplaced and dangerous worship of dead Jews. “The idea that Jewish suffering could be made to seem redemptive was likely based more on Christian than on Jewish teaching.” She deplores what has been called “Shoah business,” which would “indelibly mark the Jews as targets and also invite imitation.” She does not support the focus on Jewish victimhood rather than on “our recovery of Jewish sovereignty in the Land of Israel … the greatest comeback story on record.”

Here is where Wisse and I become sisters-in-arms—here, and with regard to our views on the systematic destruction of the Western academy in the name of “progress.” Here, I would also add the destruction of radical feminism, the erasure of sex in favor of gender identity; the focus on and the dizzying rise of transgender politics—which is only matched by the startling rise of anti-Zionist politics. Classical liberals and radical feminists have both lost the academy. In my time, I’ve seen generations of leftist feminists become more obsessed with the alleged occupation of Palestine than with the real occupation of women’s bodies and minds globally, including in Gaza and the disputed territories. The chattering classes now believe that Palestine is the most important and most aggrieved country in the world, and challenging their mighty cult—which is rooted in adamant rejection of objective fact—leads to serious punishment.

I also share Wisse’s outrage and her disdain for the rise of postcolonialism. She writes:

“After the fall of the Soviet Union in 1989, post-colonialism replaced communism as the theoretical framework of choice for the academic left, and Palestinians were touted as prime examples of the ‘subalterns,’ the oppressed. These postmodern locutions cloaked their radical intentions and added an air of mystique and authority to their war against the civilization that the university claimed to transmit.”

After Martin Peretz’s endowment of the first-time chair in Yiddish literature, Wisse was summoned to Harvard in 1993. Her behind-the-scenes description of what happened next is a riveting must read—and a cause for great despair. She charts the “academic decline” of a once-premier institution, finding that a “coercive tyranny of leftism” now dominates, a mood which has everyone “looking over his or her shoulder in fear of censure by others.” Of course, anti-Israel politics are part and parcel of the gathering “cancel culture” storm.

Wisse tells out-of-school tales and names names: Cornel West, Larry Summers, J. Lorand Matory, Leonard Jeffries, Henry Louis “Skip” Gates Jr., Diana L. Eck, etc. She writes about how Harvard President Lawrence Summers, a Jew, was falsely accused of sexism, prompting his departure, which in her view “marked a point of no return.” Thereafter, any rational and objective defense of Israel was instantly attacked and shouted down as “hate speech,” while irrational and dangerous Jew-hatred was protected as “free speech.”

Wisse reminds us that “Hitler’s men rose not from the gutter but from the university.” Her Harvard colleagues, “otherwise decent people,” still “enjoyed inverting anti-Jewish aggressors and their Jewish targets. It was an intellectual sport like no other.” Combatting these cognitive inversions and nonstop media, textbook, and internet-driven propaganda was daunting, fatiguing, debilitating, enraging, and perhaps fruitless.

Ruth has been at it far longer than I have—I’m only 21 years into fighting back against the cognitive war against the Jews—and already I’m exhausted, enraged, and even a little bored. Really, how many times can one wrestle Big Lies right down to the ground only to see them pop right up again? But there is no way I will ever leave this fight, not as long as I live and breathe.

Wisse makes several other compelling arguments, notably a thoughtful case against affirmative action. She opposes “group preferences,” i.e., quotas. “A public policy of reverse favoritism based on color and ethnicity could only deepen the insecurities and disparities one was trying to overcome.” She invokes a model of Jews as “freed slaves who needed the disciplining laws of Sinai to transform them from a rabble into a self-accountable people. I felt that condescension to the disadvantaged implied contempt rather than reciprocal trust.”

In this, she makes the point that “diversity” should not only refer to a color or sex, it should be “a diversity of ideas” and should not lead to “political-intellectual conformity.” Yes, agreed, but the entire matter is far more complicated and agonizing than she admits.

Wisse is proud of her tough-mindedness but even prouder of her sex. She believes that girls and women have easier lives than men do. I puzzled over this blind spot until I realized that she is very much like many European women of a certain class and generation. I am thinking of Hannah Arendt, Edith Kurzweil, Alma Mahler, Maria Altmann, nee Bloch-Bauer, the character that “Woman in Gold” is based upon. They are all aggressively heterosexual, proud of being man-junkies. In this, they are naive, really, understanding little about universal female suffering, a reality which is so far from their privileged lives.

Throughout the book, slowly, naively, and reluctantly, Wisse begins to consider her sex as a factor in unfair employment practices and attitudes. (She discovers that she earns less than her male counterparts.) At another moment, she asks whether “my gender play(ed) a part in (Irving Howe’s) condescension” toward (me)? Finally, she wonders whether she was hired at Harvard precisely because she was a woman. She finds this possibility ironic.

Her position on female rabbis is similar to that of Rabbi David Weiss Halivni, who parted company with the Jewish Theological Seminary over their decision to ordain women as rabbis. In his book The Book and the Sword: A Life of Learning in the Shadow of Destruction, Halivni wrote that women should be ordained as rabbis but only if they had mothers who were already Talmudic scholars, etc. Stringent, yes, but at least it is a point of view that seeks to preserve, not destroy, not dilute, the majesty of Jewish learning; a point of view which reveres rabbis primarily as scholars, not as fundraisers or political activists.

Wisse asks: “Had a cohort of female Talmudists risen to rival or surpass their teachers in mastery of sources? Had growing synagogue membership intensified devotion on the part of conservative women which required such a tradition-defying innovation?”

Halivni founded a halachic modern-Orthodox community on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, Kehilat Orach Eliezer, where he allowed women to perform only limited roles. I found it striking that the congregation that Halivni himself organized chose a learned woman, Dina Najman, to lead them. She was called their Rosh Kehilla and mara d’atra, their halachic decisor. I once heard Dina speak. I nudged my companion, my chevrutah, Rivka Haut, and whispered: “She’s a rebbe, a Talmudist, the way she gets right to the point in so few words.”

Ruth is the same way. Her book is a gift, and it constitutes a legacy, not only for her but for us all.

While we are not friends, I have met Ruth Wisse. The first time was in 2003-2004 at a conference on antisemitism in Montreal. We were both on a panel and when I finished speaking, she said: “Well, where have you been all these years?

Hineni, Ruth, hineni.

Phyllis Chesler is the author of 20 books, including the landmark feminist classics Women and Madness (1972), Woman’s Inhumanity to Woman (2002), An American Bride in Kabul (2013), which won a National Jewish Book Award, and A Politically Incorrect Feminist. Her most recent work is Requiem for a Female Serial Killer. She is a founding member of the Original Women of the Wall.