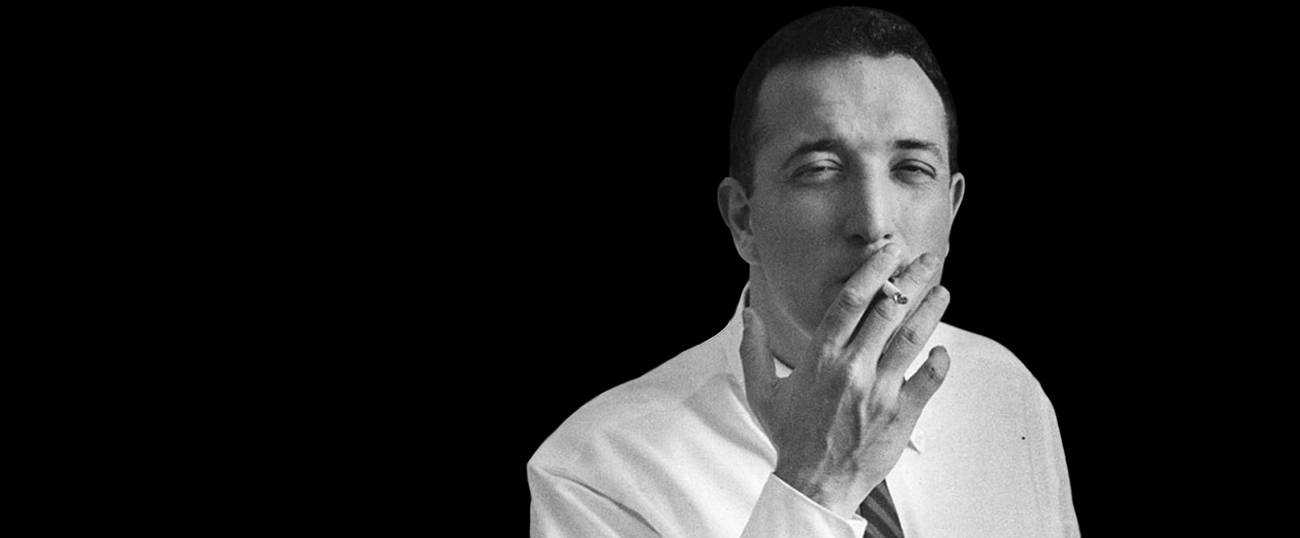

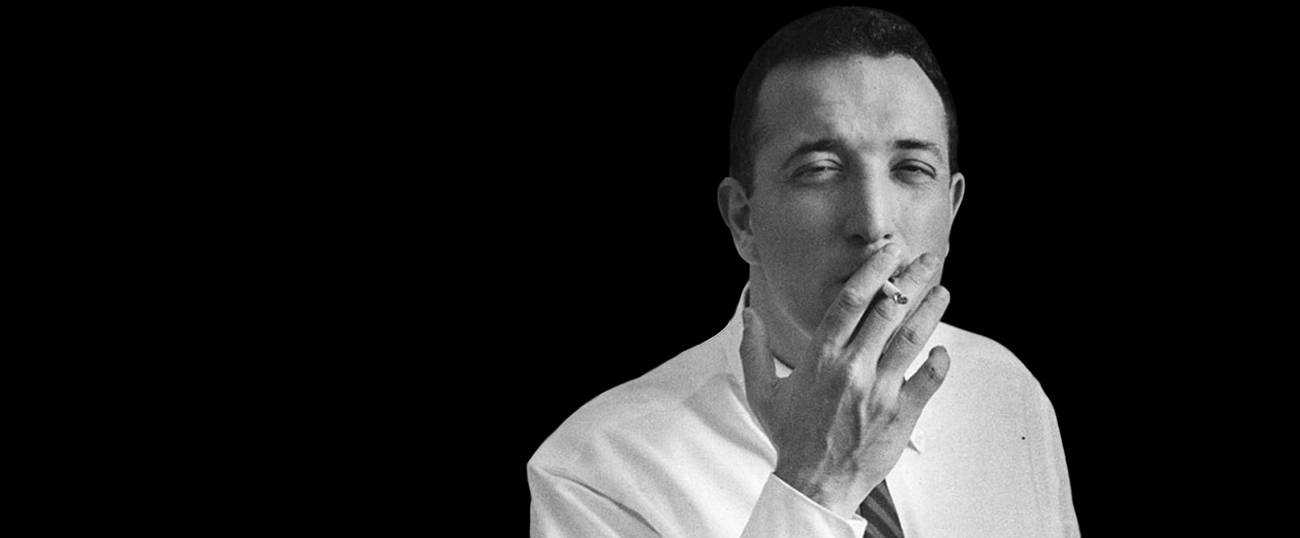

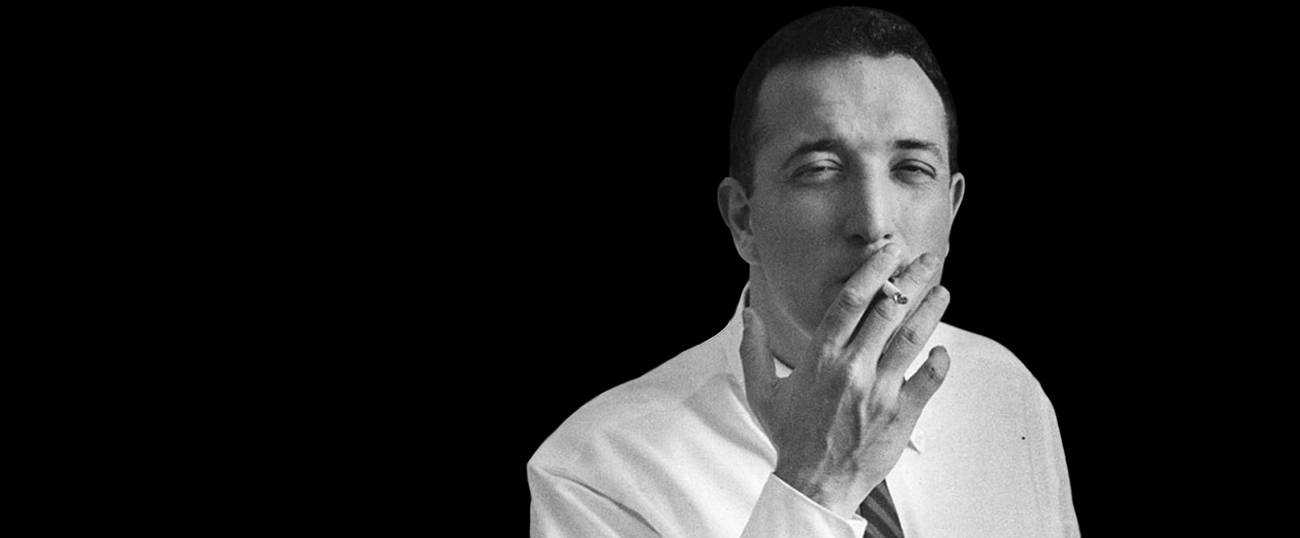

Bruce Jay Friedman, the Father of Black Humor, Isn’t Dead Yet

The master of the deadpan is on top of his game at 85 with a wise, funny new collection, ‘The Peace Process’

Bruce Jay Friedman has been a stalwart of American Jewish fiction for 50 years, ever since the publication of his debut novel Stern in 1962. Now 85 years old, he has written 19 books and several hit screenplays, including Stir Crazy and Splash. His work helped to create what we now think of as the voice of Jewish comedy—zany yet bleakly ironic, knowingly self-deprecating. Yet he has never enjoyed the commanding fame of a Philip Roth or a Neil Simon; and the Friedman-like characters we meet in his new book of short stories, The Peace Process, are uniformly haunted by a sense of not quite having made it. They are middling writers or show-business veterans clinging to the unglamorous margins of the industry, dreaming of their glory days and hoping to make a comeback.

Thus the narrator of “The Big Sister” is a former producer of Las Vegas shows who “found myself being sidelined, squeezed out” and tries to make a living putting on Chekhov one-acts on the Lower East Side: “Wasn’t Chekhov supposed to be money in the bank? Done tastefully, of course. Maybe if I’d set the plays in a bowling alley.” In “Any Number of Little Old Ladies,” an aging playwright is so desperate for a hit that he ignores his wife’s warning not to write a character based on her: “Perhaps I’m being overly sensitive, but if you don’t mind, I’d rather the whole world didn’t know about the yodeling when I climax, or the Girl Scout costume,” she tells him. As these examples suggest, Friedman’s jokes are broad and direct, and they arrive right on the beat—we are clearly in the hands of a comedy professional.

But the book’s black humor—a term Friedman helped to popularize, in his 1960s anthology of that name—amounts to more than a series of punchlines. Friedman’s real theme is the indestructibility of appetite, the way the desire for sex and fame lasts to the very end of life, when old age is supposed to have brought the wisdom to transcend it. Is there anything Friedman’s heroes wouldn’t give up for one last score? The playwright in “Little Old Ladies” gives up his marriage. In “The Choice,” a scientist named Gaylord is forced to decide between a magical cure for his paralyzed legs and winning a fairly minor prize for his work; it comes as no surprise that, after weighing the options, he can’t say no to the prize. “A chance to step out of the darkness. To step out of his hole,” Friedman writes, “To take a turn in the spotlight before the lights went out for good.” Remaining paralyzed means he won’t be able to travel ever again, but then, Gaylord reflects, “Did he need another visit to the Holocaust Museum? He’d visited five. When you’d seen Yad Vashem, you’d seen them all.”

Indeed, in one piece, “The Storyteller,” ambition even lasts beyond the grave. This high-concept tale features a teacher and would-be writer named Tony Dowling, whose one attempt at writing a novel received 75 rejections before he gave up. Now he is dead, and he awakens in Heaven to find it is “remarkably similar to the place he’d left.” However, it seems that in Heaven there are no books or stories, and a certain Mr. Hump asks the new arrival to produce one for the entertainment of the angels. Dowling tries to summarize a few classics—Catcher in the Rye, Middlemarch—only to realize that, like most of us, he can’t actually remember the full plots of the books he imagined were his favorites. With all the classics, “there was always some element standing in the way of a clear-cut story”: What is the plot of Catch-22, really, beyond “Yossarian … did not want to die in the war. Beginning and end of story. Case closed”?

Did he need another visit to the Holocaust Museum? He’d visited five. When you’d seen Yad Vashem, you’d seen them all.

Defeated, Dowling can only remember the plot of the book he himself wrote, the failure—and he finds that his reader, Mr. Hump, loves it. Vindication comes at last, though of course there is a final twist that, typically for Friedman, prevents it from being fully enjoyed. There is an element in this story of the screenwriter’s revenge on literary pretension; we seem to hear the voice of Friedman the Hollywood vet when Dowling reflects, “it was no easy matter to construct a simple, compelling gather-round-the-campfire tale. One that wasn’t tricked up and had a clean narrative that had the reader/listener wondering what was going to happen next.”

The Jewishness of Friedman’s comedy is partly a manner of familiar references and stage properties. Neurotic New York Jews and their psychologists, for instance, were favorite laugh-lines for Philip Roth and Woody Allen in the 1960s, and there is a kind of time-capsule effect in reencountering psychologist jokes in The Peace Process. There is, however, a note of genuine hostility in Friedman’s treatment of the theme that stands out as personal, something born of experience. In the odd sketch “The Movie Buff,” for instance, Friedman seems to have taken the Anders Breivik massacre in Norway as inspiration for a story about a psychologist who, out of a false sense of therapeutic duty, lets a similar criminal go free. “And Where She Stops … ” is a version of La Ronde in which a series of psychologists each visits his or her own psychologist, until the chain ends where it began. No one, clearly, has real wisdom in Friedman’s eyes; everyone is simply struggling in the dark. The only successful shrink in the book is the one in “Nightgown,” who is really an actor hired by a patient to impersonate a wise, forgiving therapist. The actor says nothing, just strokes his chin and nods, and the patient at last feels fully understood.

It is in the title story, “The Peace Process,” that all of Friedman’s favorite themes—the movie business, Jewishness, lust, ambition—come together with greatest energy. This longer piece, billed as a “novella” though it reads more like an extended riff, finds comedy in the ambivalence of its Jewish protagonist, Kleiner, when he finds himself in Israel, a country full of Jews. “As he grew older, Kleiner increasingly sought out the company of Jews. Once he was actually among them, however, he wasn’t one hundred percent sure he was enjoying himself.” (Again, Friedman’s theme—Jewish ambivalence about being surrounded by Jews, most famously embodied in Groucho Marx’s quip about not wanting to belong to any club that would have him as a member—seems to belong to an earlier generation of Jewish comedy.) In Jerusalem, Kleiner gets entangled with a young Arab, Mahmoud, who wants help getting to Queens for his brother’s wedding. Once in America, however, Mahmoud shoots to the top of the movie business, in annoying contrast to Kleiner’s own career failures. There is not a whole lot at stake in this tale, but it is expertly told and often very funny—which is enough to mark it, like the book as a whole, as the work of a master craftsman.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.