The first meal I had with François Camoin was at the all-you-can-eat buffet at the Mandalay Bay, in Las Vegas, Nevada. This was a deeply American undertaking: frivolous, super-abundant, predictive of heart disease. We had paid an entrance fee of $21.75, which entitled us to a meal fit for an African despot: lamb chops, pink and glistening, scallops scarved in bacon, shrimp scampi, chicken cordon bleu, baked ham, roasted turkey, prime rib, something called hunter steak, lobster ravioli in vodka sauce, crab cakes, baked salmon, garlic mashed potatoes, cute little baby vegetables bathed in butter—not to mention the desserts, a stadium of tiered tarts and tortes and puddings and pies, all shimmering, seeming to undulate with desire under powerful heat lamps.

We circled this absurd confluence of food kingdoms, piling our plates with foods that had no earthly business rubbing flanks. (Kung Pao chicken, meet chicken fried steak.) By we, I mean myself and half a dozen mangy writers, all of us somewhat confusedly onhand to take part in the Las Vegas Literary Festival.

As so often happens when famished writers find themselves in a buffet scenario, things turned sloppy very quickly. One of our party decided to chugalug his shepherd’s pie. Another (it might have been me) constructed an “Italian style sub,” using pizza slices as bread. In clear violation of many religious laws—as well as common decency—several of us engaged in wanton oral embraces of roasted pork loin.

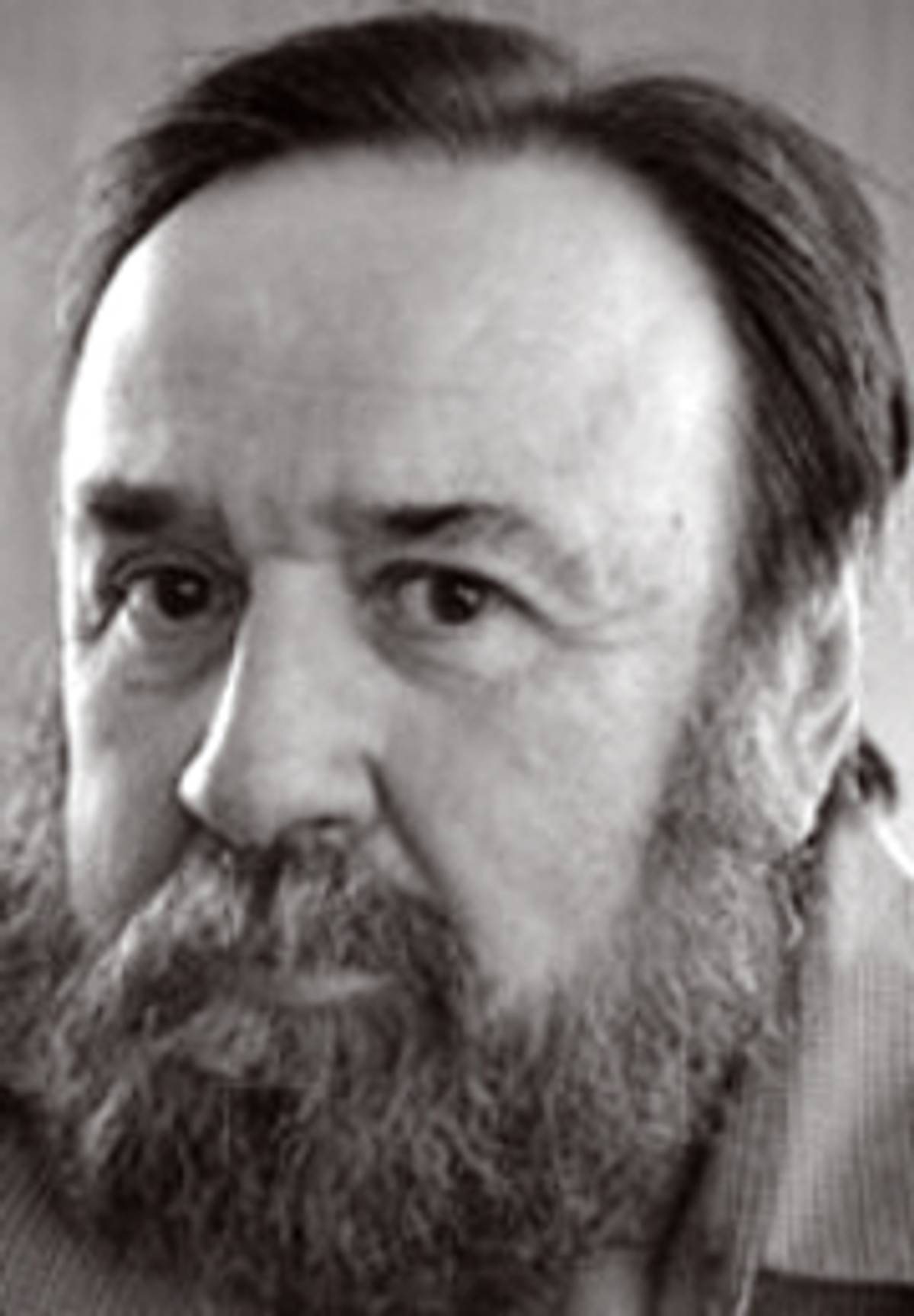

François Camoin watched these shenanigans with a look of benign forbearance. He was older than the rest of us by a good 20 years, but he seemed to understand that regression is next to Godliness in the realm of art.

When the gorging was done, we piled into a rented Buick and drove down the Strip, past the glittering chintz of pirates and pyramids and palaces, holding our bellies and bracing for the gastrointestinal recoil to come. We wound up playing poker for petty stakes in a room at the Four Queens, the downtown hotel where they’d put us up—one of a passel of hotel/casinos clustered around Fremont Street that had been considered the height of sophistication…in 1971. The bedspreads looked capable of absorbing several pints of blood. The carpets smelled of smoke and failure.

The lot of us drank and puffed pot and indulged in the expectedly tiresome verbal one-upmanship. Camoin seemed happy enough to listen to our prattle. His hair was wispy, his beard white, his eyes blue and tired.

I didn’t think much about him that first night, because my girlfriend Erin was on-hand. We lived 3,000 miles apart back then, and the trip to Vegas was mostly an excuse for a conjugal visit. It never occurred to me that I was in the presence of literary giant. That’s the sort of idiot I am.

I hope you will not beat yourself up too elaborately for not having heard of the Las Vegas Literary Festival. It is not quite yet a marquee event. The problem isn’t with the talent or the funding (both abundant), but the audience (essentially nonexistent). It turns out that Vegas has a small community of readers once you exclude the Daily Racing Form.

There was also the problem of locale. The festival events took place in and around the main library, an area referred to in local guidebooks as “The Cultural Corridor.” I will withhold comment as to the appropriateness of this moniker, other than to place into the record the following exchange, which took place just before a panel on humor writing.

Writer 1: Did you see the guy on the steps outside?

Writer 2: Which guy?

Writer 1: The one shooting drugs into his bloodstream with a needle.

Writer 2: You’re kidding, right?

Writer 3: Maybe he’s a fan of Burroughs.

Within 48 hours, my lady and I were clinically depressed. We lay in bed and listened to the clink of money down below, the hopeless sounds of debt accruing. It was all we could do to fling civic mottos back and forth.

Las Vegas: Luxury and Suicide in One City!

Las Vegas: Your First Seating at the Apocalypse!

Las Vegas: Greed Served Cold!

Camoin read on the final day of the festival. I nearly blew it off. But the guy seemed so nice and I knew the crowd was going to be sparse. So I was one of a dozen folks there to hear him read a piece called “American Literature.” It was clear from the start that Camoin was no schmo. Then came this line:

We walked down Bleecker Street with the wind; yellow dogs and bums crouched in doorways, beaten by life. Marty’s talk was filled with subtle dislocations of language that made my head ring. Fat cars trembled at the intersections, breathing steam. We walked.

I had not heard prose of this sort—fearless, exalted, precise—for quite some time. The story concerned a pair of aging Jewish machers who stumble from a poetry reading to a liquor store, which Marty, King of the Stockbrokers, decides to hold up, lecturing the terrified clerk about literary matters until the cops descend. The story was uproarious, wise and shocking, a tribute to the liberating joys of unreasonable risk. By the time Camoin was done, I was in full rapture.

Camoin smiled at the smattered applause. Then he pulled a box from beneath his chair and handed every person in the room a copy of his story collection Like Love, But Not Exactly. We tried to give him money for the book, but he shook his head. These were gifts. The book was out of print, he explained shyly.

I read the book as soon as I got back from Vegas. Then I read it again. His four leading men were Jews stumbling through late middle age, New Yorkers who despise and love each other in about equal measure. They were, as a group, stunned before their own capacities for trouble—schmendricks who fail ecstatically. Most remarkable were Camoin’s sentences, which bristled with the supple dynamism of Bellow, the jazzy patter of Elkin:

In the water below, shadowy fish move like dark ideas of fish.

A month goes by; it’s spring, which in New York is a serious enterprise, a time of resurrection, very traditional, very compelling.

The party dragged. Meyer drank sparingly; he wished he could drink more, make himself disgusting and perhaps happy, but he knew it wasn’t in him to let go of reason and dance.

I was in love.

And as so often happens when I fall in love with a writer (or musician or visual artist) I started to feel that crazed groupie indignation that Camoin was not better known, a feeling that zoomed into the stratosphere when I discovered that all six of Camoin’s books (two novels, three original story collections, and an anthology of selected stories) are out of print. Huh?

* * *

The second meal I ate with Camoin was in Salt Lake City, where he has lived for two decades, directing the creative writing program at the University of Utah. I was in the midst of driving Erin from Southern California back to Boston. We were married now, Erin was six months pregnant, her car was crammed with all her earthly belongings.

I wanted to ask Camoin how he could write so well, to so little regard, but the dinner was another chaotic affair. My wife was surrounded by women who had given birth, who assailed her with various terrifying labor stories. Camoin was surrounded by admiring former students, who assailed him with their needy attentions.

I didn’t blame them. I could see at once that as a teacher Camoin was wise, generous, and patient to a fault the same way he’d been in Vegas. What struck me hardest was the incongruity between Camoin’s gentle manner and his fiction, which is so often audacious, even anarchic.

It made me wish I’d studied with the guy, or better, that we’d been born into the same family (with him as a far-flung uncle, or some glamorously bohemian cousin), though of course we were born into the same extended family, the troubled, dreamy family of Jews.

And this—along with my abject worship of his prose—led me to conclude that it would be best to skip a third meal with Camoin and proceed directly to an interview, in which I could ask him a series of questions that might reveal to me the secret pleasures of my own sorrow.

* * *

I reached him in the midst of his end-of-the-semester anxiety. “Then again,” he noted, “anxiety is where I live anyway.”

Right.

Given the overt Judaic feel of his fiction, I wondered whether Camoin regarded himself as a Jewish writer, or just a plain old writer. As it turns out, his religious status is complicated. He grew up in a middle-class Catholic family in France until he was nine, at which point he moved to New York City to live with his mother and her new Jewish husband. His stepfather’s family was Orthodox, though he didn’t practice. How’s that for cultural whiplash?

“I live in the world as a cultural, existential Jew,” he told me, “and I guess I write from there.” To be clear: Camoin underwent no formal religious study, and he doesn’t practice. It’s more a matter of affinity: “As I got older I found that many of the people who seemed to be on the same wavelength as I was were Jewish. And then also I taught the Bible for many years as part of a Western Civ course, and I found myself much more drawn to certain books of the Old Testament than to anything in the New. There’s nothing in the New Testament to compare to Job, Ecclesiastes, Isaiah…I feel at home with Jewish craziness, while WASP and Catholic craziness makes me angry and fearful.”

It’s worth noting that Camoin’s mother did convert to reform Judaism in the last couple of years of her life. “I think she saw it as a religion based on ethical behavior and thought rather than faith in the supernatural—that’s what appealed to her.”

This line of questioning led—inevitably, obnoxiously—to the Big What If? “As for God, I haven’t seen one I’d care to believe in, except maybe (and that’s where the Jewish thing comes in) the one whose name can’t be written, who is inconceivable. Does he exist? I’m keeping an open mind. But I’d take the other end of Pascal’s bet every time, if I had to choose.”

Not surprisingly, he claims Bellow and Elkin as his chief literary influences, though instigators is the more accurate term. “I never went to grad school in creative writing,” Camoin explained, “so they were my teachers, though they didn’t know it. Well, Elkin did, just before he died, I had the chance to tell him, which was nice. For me, at least.”

Camoin shares Elkin’s verbal exuberance, but also his fearless capacity to find the absurd comic moments within tragic circumstances. I think here of the story “Lost in the Desert of Love” which appears in Like Love, But Not Exactly, and in Baby Please Don’t Go, the fabulous anthology of Camoin’s short fiction.

The story focuses on the depressive Meyer, who botches his suicide attempt and winds up following a crazed anti-Semite into the desert. The reader braces for an assault. Instead, the man makes a pass at Meyer. Then both men fall asleep. Then this: “When he woke up, a full moon floated over the goatish hills, poised there by love’s ineluctable gravity, dimming the lesser stars and casting a pale light on the other man, who Meyer found out when he touched him, was, after all this, dead.”

It might be said that Camoin has made his own pilgrimage to the desert, having settled in Salt Lake City. I was curious how he came to settle in the world capital of Mormonism. “I came to Utah because they offered me the job,” Camoin noted simply. “But also because I like the landscape of the West, the desert, the dryness, the whole thing not smothered by vegetation, the bones of the earth that show through.”

He added: “I’m a stranger by nature and choice, so living among the Saints doesn’t make me feel any less at home than living in New York or Ohio or the upper reaches of the Zambezi River. Camoin among the savages.”

I rather like the image: one of our finest, and most overlooked, modern writers, living a quiet and determined life in the high, Technicolor desert, surrounded by blond zombies with fabulous teeth. It’s like something out of one of his breathtaking stories, which, come to think of it, you should find and read. At once.