A Soviet Drop-Out’s Journey to Freedom

In search of the traces of my refugee transit camp in Vienna, on my way to America

Svetlana Boym, the author of this piece, died in early August, at the age of 54.

***

The little that remains of the memory of my refugee camp from the early 1980s is in extreme close-up: a breach in the concrete wall with barbed wire, a foot in a mended sock dangling from the upper bunk bed, an unzippable suitcase filled with obsolete things, a roll of the foreign toilet paper, pink like the fairy in The Wizard of Oz. And no establishing shot.

To tell you the truth, none of these things bothered me for decades. No pictures from the transit camp have been preserved and no address. I happily forgot my forgetting. My emigration from Leningrad to Boston had a few detours, gaps, and loose ends. But the point was not to travel on memory lane but to move on, to begin again. Why remember the unmemorable?

In the Soviet Union of the 1980s there was a code word: “to leave.” If you whispered it with a mysterious gravitas, there would be no need to ask further questions. To leave meant to flee once and for good. You knew well your point of departure but not necessarily your destination. To leave was an intransitive verb that marked a break in space and time. You might as well be going to the moon or to the Underworld. Farewell parties in the 1970s and 1980s resembled funerals in their finality.

At the age of 19 I decided to emigrate and had to leave the country without my parents. I was stripped of citizenship and told that I would never be able to return to Leningrad and see my family. The “personal search” all of us went through at Customs lasted many hours and included intimate parts of our bodies and of our personal belongings. The Customs officers enjoyed the procedure. They fingered every scratch on the few family pictures, counted the number of permitted individuals in the group photos, penetrated every seam in our clothes, patted the inside lining of our oversized rusty-zippered suitcases in search of “the second bottom.” Since then I always want to travel light, but more often than not, the zipper on my carry-on bag still doesn’t come together till the last pull.

My father remembers the moment of my departure with a cinematic clarity. It took place at the gate in the Moscow Airport reserved especially for those who were “leaving for permanent residency.” I said the last good-bye and moved behind the glass where my parents could still see me go through the next Customs gate. Another departing family, standing in line behind me, consisted of a young couple holding a baby and pushing a baby carriage and a grandfather carrying a large manuscript that was clearly invaluable to him. “Either the manuscript or the baby carriage,” said the Customs officer. Whatever that manuscript was, this was the one thing the grandfather could not part with. “To hell with you,” the young mother shouted and pushed away the baby carriage. At that moment I disappeared behind the glass. The baby carriage rolled slowly into the empty corridor and down the steps. An uncanny afterimage, courtesy of Sergei Eisenstein.

It was another seven years before my parents saw me again. In my family we are used to leaving longing behind together with personal belongings and to treating nostalgic tales with a grain of salt.

My “journey to freedom” was short in time and cosmic in proportion. This might have been the first time in my life that I traveled by plane across the border. In the Vienna airport I caught a glimpse of the spring sky framed by the ramp and a frivolous sign “Duty Free,” which I couldn’t decipher. We were greeted by the representative of the organizations assisting refugees and quickly herded into unmarked buses with darkened windows and transported to the outskirts of Vienna or somewhere else. We had no idea where we were and didn’t ask indiscreet questions.

The first impression of the camp was disappointing. The place resembled a provincial military hospital or a monastery. Is this what the West looks like? Neither terrifying nor exhilarating, just banal. Among the transient residents of the camp were Jews from all over the Soviet Union, from Central Asia to Leningrad , Poles fleeing military law, Crimean Tatars, and a Russian Protestant escaping religious persecution. The camp was operated by several Jewish philanthropic agencies and guarded by Austrian soldiers with friendly German Shepherds. The latter were supposed to protect us from any attack from the outside. From what I remember, we worried little about that and just wanted to catch some rest and dream about the future. We took walks in the camp yard but never went outside the walls. Men told one another erotic dreams to fall asleep, and women kept their dreams to themselves. We ate plenty of comfort food and sweet bulochki and filled out many forms that itemized our hyphenated identities. Movies were shown all the time.

I would like to give you a more detailed description of the camp, to provide you with snippets of conversation between the emigrants on the upper bunk beds and emigrants on the lower bunk beds, their tired jokes and discussions of the meaning of existence, to convey the anxious whispers of the social workers and armed guards, to provide lifelike images of narrow beds with broken springs, the archives of classified documents next to the trash storage, ruined warehouses in the walled monastic yard where brown pigeons pecked at the cones of the local evergreens. I’d like to share with you the taste of the sweet bread soaked in the weak tea, the homey camp pasta with Viennese sausage and on the movie screen a flickering image of the sun-kissed athletic men and women building a city on the sand with song and dance. Only I don’t remember any of that, and I’d rather not fill the gaps with a plausible fiction.

We never saw the Vienna that we dreamed about, the city of Mozart and Freud. We remained extraterritorial. Like the Freudian unconscious, our transit camp had no outside; it was a place out of place and a time out of time. I don’t know how long we stayed there. It felt like we were in a time capsule, a place where there was no present, only the repressed past and the unknown future. Actually I had a good camera with me, a Leica or Zenith with a high-precision lens and a long zoom. Of course, it never occurred to me to use it. The camera was meant to be sold at the flea market in Rome together with Ukrainian linens, nesting dolls and caviar, to save some money for the rainy days “in the West.” I studied photography as a teenager, experimenting with reflections on rippling water and urban panoramas. It never crossed my mind to photograph anything in the camp. There was nothing there “to write home about.” New immigrants like to make cheerful pictures next to other people’s houses and bright cars. The camp didn’t seem worthy of a photograph.

***

Fifteen years after leaving the camp I became a photographer. I returned to photography as suddenly as I’d dropped it before. My digital camera has a few special effects that imitate the old Leica, but I don’t use them. Since the late 1990s I’ve been documenting my travels through the world, collecting errors, overexposures, chance encounters. I have been taking pictures of the places that I would otherwise not remember.

Once during my presentation at the Vienna Kunsthalle commemorating the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, a man in the audience asked me a question about art: “Why do you photograph the same landscape in different places?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “These are just transits, warzones, afterimages of something we see and forget.”

“So, is this your first time in Vienna?” he continued, changing the subject.

“No. The first time was in 1981. In a refugee camp,” I said surprising myself.

“Really? What was it like?”

“I don’t remember much.”

“Where was it?”

“Nobody knew.”

It is then, during my second visit to Vienna that I decided to find the address of my former camp. Just to take a picture of it, to fill the gap. This would be a photographic project, not a nostalgic trip down memory lane.

My initial research into the location of our transit camp proved futile; the more I prodded, the more mysteries I encountered; they hid one inside the other, like the nesting Matryoshka dolls that we carried in our overburdened suitcase. It was clear that the break in my personal memory went together with a lacuna in collective history. After 30 years the address of the camp remained strictly undisclosed. The extraterritorial refuge for extralegal immigrants was not to be found on the Viennese maps or in the archival records. Our story was deeply embedded in the inconvenient histories of the Cold War as well as in the improbable adventures and acts of courage of many individuals who brushed that history against the grain. We were mere extras to history who found a temporary shelter in the provincial hospital behind the thick wall with barbed wire.

The city of Vienna that we didn’t get to visit in the 1980s was a magnificent sleepy capital of the fallen Habsburg Empire, which had disintegrated after the Great War and after the Second World War turned into a small “non-aligned” country at the crossroads of East and West. Vienna carried its war scars quietly, observing the code of silence when it came to confronting its recent history. Black-and-white documentary footage showing the Viennese happily greeting Hitler, the native son, in 1938, were not very popular during the 1980s, when Austrians preferred to see themselves as victims of Nazism and avoided going through the “management of Nazi memory,” as the Germans did. Equally not addressed were the years of the occupation of the city by the Red Army, which liberated Vienna from the Nazis in 1945 and remained in the city until 1948, almost turning Austria into one of the Eastern bloc countries. It was not by chance that postwar Vienna became a stage-set for many Cold War movies, from the shadowy black-and-white Third Man to the Technicolor James Bond in The Living Daylights. Sometimes when film directors couldn’t get a permit to film in the Soviet Union, they would film the backdrop for Petersburg-Petrograd-Leningrad in the baroque squares of Vienna. From the 1970s through the 1990s, Vienna became an inconspicuous transit point for the many refugees from Eastern Europe.

Legal immigration from the Soviet Union was allowed under the leadership of Leonid Brezhnev for pragmatic economic reasons and due to the pressure from Jewish communities abroad. In the United States, the Jackson-Vanik Amendment denied most-favored-nation status to certain countries with non-market economies that restrict emigration, which was considered a human right. In order to get economic benefits and subsidies, the Soviet Union grudgingly signed the Helsinki agreements that allowed family reunification and immigration, especially for individuals of non-Russian nationalities who had families abroad—Germans, Greeks, Armenians, and Jews (which was considered a “nationality,” according to the fifth line in the Soviet passport). While the official reasons for immigration had to be strictly personal and nonpolitical, in many cases family reunification was used as a pretext for more political choices or quests for a better life. Prospective emigrants pretended that their reasons were merely familial, and the authorities pretended that they believed them. The government also exploited the situation for its own benefit, pressuring undesirable individuals in the country to accept the “family visa” and go into exile. The lasting support of the American Jewish communities played a crucial role in enabling the Soviet Jewish immigration and resettlement in the United States.

Actually, the movement for Jewish awareness and later emigration began inside the Soviet Union after the anti-cosmopolitan campaigns of the late Stalin era (1948-1953), which targeted Jewish doctors, teachers, and scientists who were accused simultaneously of Zionism and cosmopolitanism, of left and right “deviations.” The movement for immigration grew in the late 1960s to early 1970s and reached its peak after the Yom Kippur War. It followed a specific route. Individuals desiring to leave the USSR had to receive an invitation from Israel, often from complete strangers who pretended to be close family. Then they would apply to OVIR (the State Agency for Visas and Immigration, supervised by the KGB) and be placed under a permanent supervision and in limbo for months or even years, experiencing varying degrees of deprivation, harassment, and financial stress. At the end, by luck of the draw, they would become either refuseniks or refugees.

After my departure, my parents were denied permission to leave for the next six years. My father was denounced in his factory by his friends and colleagues as “the traitor to the motherland” and subsequently lost his job as an engineer. For five years he served as a part-time night guard, and their apartment was under constant surveillance by the Leningrad KGB, the alma mater of the current Russian president.

Those who received permission to emigrate from the Soviet Union before perestroika were stripped of their Soviet citizenship and most of their personal belongings. They were allowed to carry with them one suitcase per person and $99 in cash. Their only document of identity was the Soviet “exit visa” with no entry visa to any country. This group had a choice between going to Israel or pursuing an alternative route through the transit camp in Vienna (later substituted by hostels and pensions in the city) and then in Ostia or Ladispoli, where they were interviewed for political asylum in the United States, Canada, Australia, or New Zealand. Europe, with the exception of Germany, didn’t grant asylum to Soviet Jews. The Soviet Union didn’t have an official diplomatic relationship with Israel, and the Soviet authorities chose Austria as a stopover for refugees. This is how we had found ourselves on the outskirts of the invisible city of Vienna.

I began to understand what our Vienna transit might have looked like from the outside with the help of the article “Tales of the Vienna Airport,” by Joe Nocera, which appeared in Harper’s Magazine in 1982. Trying to make sense of the dramatic transport of refugees from the Soviet Union, Nocera came to a paradoxical conclusion. Each country involved in our transit was creating its own diplomatic half-fiction. This included the Soviet Union, the United States, Israel, and Austria. Moreover, these half-truths didn’t impede the process of immigration but actually enabled it. In other words, if there had been a hypothetical classified information leak, or if a particularly vehement investigative journalist had revealed all the arrangements made between the Soviet Union, Austria, the United States, and Israel, our transit might have not taken place. As for me, I was just grateful to all the organizations that made the passage possible and considered it as a gift. As the proverb goes, you don’t check the teeth of the horse that you got as a gift.

First and foremost a humanitarian shelter, the camp was also a site of awkward political arrangements. The Austrian chancellor at the time, Social democrat Bruno Kreisky, agreed to take on a humanitarian role in the passage of the Soviet Jews, but he did so obliquely. The first transit camp organized by Kreisky’s government was at Schoenau Castle, close to Vienna. This camp was closed after the terrorist attack, by the groups Black September and the Eagles of Palestine, on the train carrying Jewish immigrants from Ukraine via Bratislava to Vienna. To make a long and controversial story short, in order for the captured hostages to be released, after tense negotiations the chancellor of Austria agreed with the terrorists’ demand to close Schoenau Castle. However, unofficially, Kreisky continued his commitment to house the refugees, except he moved them to undisclosed and heavily guarded locations: first to the military barracks in Woellersdorf and then to somewhere in the territory of the Red Cross in the district of Simmering.

Since I didn’t have the exact address, I began to wander through Simmering virtually, with the help of Google Earth. After all, the family of the founder of Google, Sergei Brin, took the same immigrant route as I did. Simmering has a long history; it was a medieval village with a famous brewery and a church. Later, it became an industrial district of Vienna known for its material recycling industries and the Gasometer featured in the Bond movies. I came across several articles in the local Kronen Zeitung newspaper from August and September of 1974 that reported local protests against placing a transit camp for Jewish refugees in their neighborhood in Simmering: “We will not cease to protest against this camp, which is a danger for all of us, particularly for our children,” stated Angelika Kneth, 34, mother of four children, who objected to the presence of armed guards and barbed wire near the kindergarten. The interior minister of Kreisky’s Social Democrat government, Otto Roesch, tried to reassure the local residents: “We have to fulfill a humanitarian task. Everybody must understand that it is our duty to help other people.” An irony of history: It was later disclosed that Mr. Rösch had once been a Nazi storm trooper.

My main lead in my search for the material traces of the camp was an Austrian documentary filmmaker with a Russian last name, Alexander Schukoff, who made a film about the district of Simmering in 1977-78, a few years after the opening of the camp. I hoped that after filming for a year in the neighborhood, he might have its address. “This is what you would have seen if you had been allowed to leave the camp. I give you a bigger window now,” said Mr. Schukoff, graciously offering me his film as a gift. The film was a poetic meditation on the working-class district of the metropolitan city that Viennese rarely visit. Located between the cemetery and the airport, it was home to the Viennese fiakers who do nostalgic sightseeing tours of Vienna in horse-drawn carriages and at night return to unspectacular Simmering, which looks like Eastern Europe. Local residents, young and old, complain of boredom, of the fact that nothing has ever happened in Simmering.

Schukoff’s film makes no mention of the refugee camp that existed for 10 years on the street around the corner. The director confessed that he had no information about it. What about the neighborhood protests in 1974? He wasn’t doing investigative journalism, but cinema verité. While being faithful to the ebb and flow of local daily life, he might have missed the biggest Cold War story that was unfolding in Simmering and in Vienna at the time. Or perhaps he got the story right: The camp remained extraterritorial. It existed “off” the Viennese map, disconnected from the rest of the city. Cinema verité captured the site’s eerie invisibility.

I decided to look for more history in the archives of the HIAS (Hebrew International Aid), one of the organizations that supported our transit and resettlement in the United States. Director of Family History and Location Service at HIAS Dr. Valery Bazarov greeted me with open arms but warned me that he didn’t have the address of the camp in Simmering. He offered to order information from the deposits the HIAS archive—“Vienna files” from the 1980s. They contained everything that has been declassified, excluding personal files. Among the documents that caught my attention were: a check from an Italian man who wanted “to support the Jewish people after World War II”; a passionate letter from a case worker who advocated the Jewish refugees’ right to choose their place of emigration, be it to the United States or to Israel; a case documenting the mysterious disappearance of the HIAS Hungarian translator who might have been a secret policy agent; and a telefax from the Austrian interior ministry that demanded that the refugees in the transit camp be informed about their rights to demand political asylum. Since I already knew that, at the time, most West European countries tried their best not to offer political asylum to the Soviet Jews, I copied the telefax and buried it in my folder as another example of the half-truth practiced by the Austrian government. As for the Hungarian agent-translator, apparently he remained at large with a huge sum of money, and the passionate social worker won her case. Apart from those few intriguing documents, most of the HIAS files were tantalizingly unrevealing. They contained minutes of administrative meetings, requests for new furniture for the HIAS offices, and the instructions on how to understand and handle the noshrim, or dropouts, whose numbers were growing. I was puzzled by the terminology.

“Who were those ‘dropouts?’ ” I asked Mr. Bazarov.

“You,” he answered smiling.

Dropouts were those of us who “dropped out” of going to Israel, the destination on our exit visas, choosing the limbo of the refugee camps and hoping for trans-Atlantic emigration.

I looked up a few of my fellow dropouts, whom I didn’t know at the time but who subsequently became my friends. None of them was particularly interested in finding the location of the camp. The idea of the “camp reunion” left them cold. They approached the conversation with a healthy dose of skepticism.

Why revisit the camp now? We were very tough then because we knew how to forget; if we start remembering now we could risk our immigrant resilience. Obsession with the past might shortchange our future. “Is there is a change in your life now that makes you look back at that first big break?” one friend asked.

“I just want to take a picture of it,” I said, not too convinced myself.

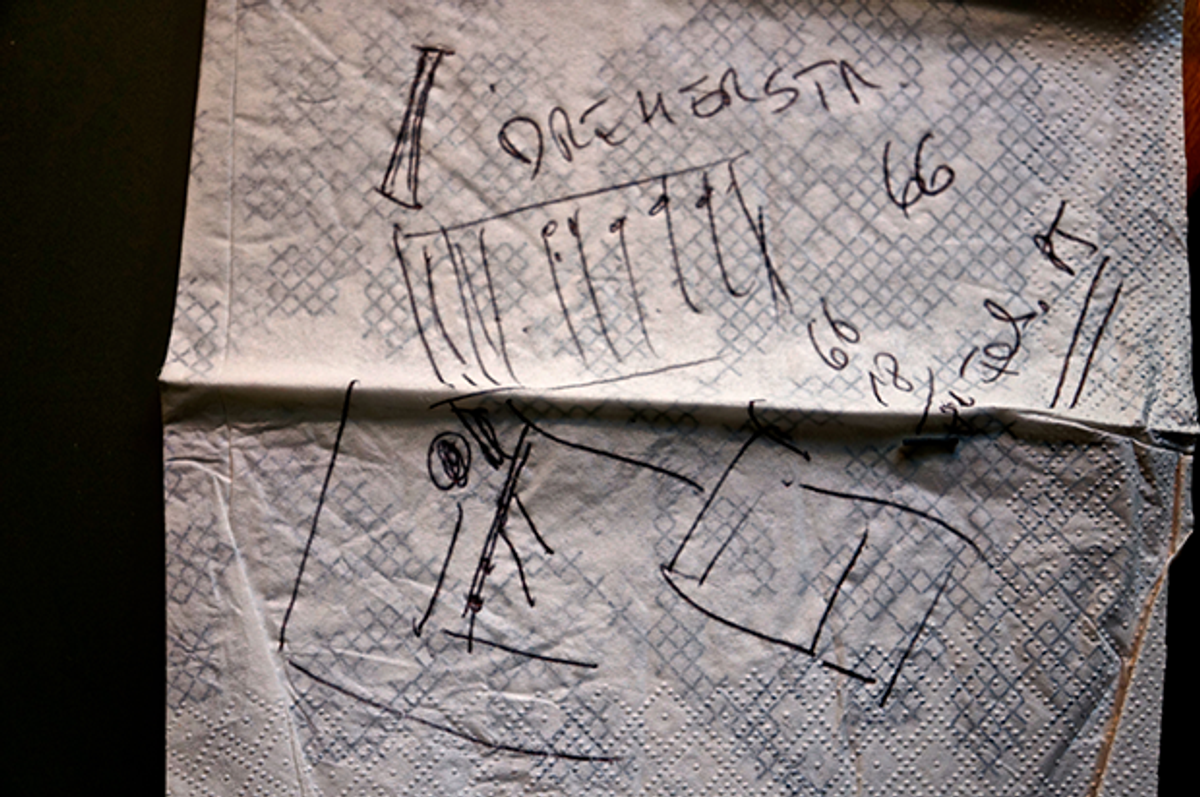

My former campmates had their own blind spots next to vivid memories. Most interviews happened surreptitiously, in transit or in between other important tasks; they were not fully recorded. I asked my witnesses to draw a picture on a napkin of the camp as they remembered. Now this strange collection of paper ephemera, stained with garlic oil and cappuccino, offers a collective memory map of what the camp might have looked like.

Writer and journalist Masha Gessen, who was 16 at the time of immigration, recalls her disappointment at the sight of Austrian guards with German Shepherds: “I thought I was immigrating to the ‘West’ and then I found myself in the camp. My parents must have deceived me; the West was the camp.” By contrast, Masha’s younger brother, writer and editor Kostya (Keith) Gessen, age 6 at the time, enjoyed his stay. “It didn’t look like a camp,” he said. “More like a hotel, yes, a nice hotel with the yard. I had a good time there.” The singer Regina Spektor, who was the same age as Kostya, didn’t think it was a nice hotel: “There was no floor there, just bunk beds everywhere,” she recalled.

My witnesses couldn’t agree on the geometrical shape of the camp yard. Art historian Anna Wexler Katznelson, 6 years old at the time of emigration, claims that the camp yard resembled a black square just like the famous painting by Kazimir Malevich. Artist Vitaly Komar, who passed through the camp as a grown-up, said that the yard had the shape of a mandala. At present Vitaly is working on the artistic project of transforming and sometimes reconciling symbols of different religions. The shape of the yard echoed his own psychic geography. “Of course, I was keeping records in the camp,” said Vitaly. “My notebooks with little squares were with me. Only my records had nothing to do with the place I was in. I was putting down my thoughts on art.”

Curator and artist Anton Vidocle, age 15 at the time, commented that the camp looked like a high school, sort of like PS1/MOMA in Queens. He had no recollection at all of his departure from Moscow, but a “photographic memory” of the camp movie theater and the new suit with red stripes that he wore there. He knew all along that the dogs and the armed guards were on our side and were protecting us from the outside. He wasn’t scared of them. He remembers most fondly an erotic conversation he eavesdropped on in the collective ward. “It must have been the famous Story of O. I was completely taken by it.”

Designer Constantin Boym noticed the unusual shape of the prewar window in the camp ward. Not being able to fall asleep, he peered through it chasing glimpses of the outside world. He saw a stranger walking on a dark street. “That’s the West, I thought,” said Constantin smiling. “All I wanted is to be that man strolling somewhere outside the camp. Look, maybe it doesn’t matter what actually happened in the camp,” he added at the end. “What matters is the camp of memory. Or art.”

Indeed, why seek a physical confirmation for our unbelievable stories? The emigrant is a bit of a trickster who moves laterally like a knight in the game of chess in order to survive. Maybe it would have been more accurate to re-create the camp of our escape dreams that transported us beyond the thick concrete walls. And such a camp wouldn’t require a precise address.

It dawned on me that my camp mates and myself might have been afraid of the same question that I never dared to ask: Why did you leave? Or worse: Did you ever imagine your life otherwise, without emigration?

I always believed that I couldn’t. My emigration had begun long before the actual departure and has lasted long after the arrival. I might have started expatriating myself when I still lived in Leningrad as a teenager and heard for the first time my grandmother’s story about her life in the camps of the Gulag.

My grandmother, Sara (Sonya) Goldberg, a secondary-school teacher in Leningrad, was rounded up in 1949 during Stalin’s anti-cosmopolitan campaign aimed largely at Soviet Jews including atheists and those who changed their names and official nationalities. Grandma Sonya considered herself “lucky”; she spent only six years in the Gulag, instead of 10, thanks to Stalin’s death. Fifteen years later she was “rehabilitated” for the “absence of the content of the crime.”

My grandmother’s story had many blank spots because for 20 or so years nobody in the family talked to her about her life in the camps. Without conversations, the memories turn into stones or fairy tales. I inherited her blind spots and her fears and have carried them with me through life. She didn’t know either where her camp was located within the vast zone of the Gulag. She never talked about how she resisted arrest and tried to cut her veins. Instead she remembered tricking the informants in the camp who wrote reports to the authorities, and mostly she loved to recall her friendship with the actress Tatyana Okunevskaya and how in the difficult moments they recited Chekhov: “One day we will see diamonds in the sky. You will see that day will come.”

What I gathered from the fragmented tale of the camps that she told me when I was 11 was that there was another unwritten history and another secret territory outside the official maps, a camp zone where millions of Soviet citizens were detained without having committed any crime. In the 1970s my grandmother became a kitchen dissident. While cooking her soup, made with the skinny chickens that she got in the market for one ruble and five kopeks, she listened to the jammed Voice of America. For years she cried over the death of Kennedy and regretted the end of the Prague Spring. Sometimes she only imagined what they were saying on the radio, since the sound was jammed. She would just stand there whispering something to the faraway addressee, a prayer or a poem, as she looked through the unwashed window into our dark Leningrad yard.

My emigration can be considered political since I took part in several demonstrations protesting human-rights violations, yet at that time my understanding of the political was rather vague. It was a blend of the existential dreams of liberation that we saw in foreign movies and a rebellion against the local coercion and claustrophobia of Brezhnev’s time of stagnation that threatened to destroy all of our teenage ideals of justice.

I could blame the great Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni for seducing me with his long cinematic takes that promised an unforeseen freedom of movement. My father organized a film club in the Palace of Culture in the Petrograd district of Leningrad, which became his little homeland. In his words, it was a state within the state that also provided good babysitting for the children of the club-goers, those rebellious Leningrad pre-teens like myself. Almost no American films were shown in such film clubs, but there were plenty of Polish and Czech existential tales as well as the films by “Italian Communist filmmakers,” filled with existential mysteries and wonder. I loved The Passenger (Profession: Reporter, 1975) more than the others. It was the story of a journalist (played by Jack Nicholson) who chose to radically change his life and adopt the identity of a dead man, who was a traveler and an adventurer. At the end he encounters a beautiful and mysterious woman (played by Maria Schneider) and finds his match in the existential adventure of life and death. I didn’t watch the film for the complex plot of mistaken identity but for the long takes and eccentric vistas into a foreign life. I was particularly taken by the free-spirited and edgy Maria Schneider who criss-crosses the borders somewhere in the Pyrenean mountains, just to study architecture or to meet strangers. I never saw women and borders like that. The film was explained to us as a “Marxist critique of bourgeois alienation,” but it felt more like a cultural luxury, a quest for freedom and creative living. There was a breeze in the heroine’s hair and the long duration of a non-obligatory time that shaped my dreamscape. I had to emigrate, go through several transit camps, and work hard for years before I could enjoy again this kind of wanderlust.

My first border crossing hasn’t resembled anything I ever saw in movies, and yet movies remain among my most vivid memories of the camp. The camp “film retrospective” included Holocaust movies and various comedies on Jewish subjects. We were extremely ignorant, since any study of Jewish culture was virtually prohibited in the Soviet Union and frequently considered either “cosmopolitan” or “Zionist propaganda”—the two contradictory terms were used interchangeably. We knew that we didn’t want to try on the exotic Eastern European Jewish attire from another time, which appeared foreign to us. When the representative of the Jewish agency tried some authorial tactics to convince me to go to Israel, I answered that I didn’t want to go to the country of Fiddler on the Roof. This was an embarrassing mixture of ignorance and chutzpa. I didn’t realize then that I had just left one of the film’s homelands, Russia, and was about to arrive for permanent residency to the United States, where the poor fiddler found his cinematic home. It took me 20 years to truly discover Israel and to acquire a more balanced view of the history of emigration. This serves me right. All pain aside, some of our camp experiences had an element of absurdity to them and resembled a chance encounter between Woody Allen and The Third Man.

In 2012 I decided to go back across the border, not just to visit Vienna but to go to Simmering and scout the location. Before my departure I nervously looked through the copies of the “Vienna files” that I obtained with kind permission of HIAS. I reread the article from the New York Times, perused the case of the cunning Hungarian translator who dealt in more than metaphors, unfolded the telex from the Austrian minister of interiors who suddenly seemed to care about the plight of the refugees. Just as I was ready to put the paper back into my drawer, I spotted the fainted typewritten letters in the fold at the bottom of the page with the exact address of the camp. I couldn’t believe my own eyes. I had possessed the address for a year. It was hidden in plain view, in the fold of the Xerox in my desk drawer that I used every day.

A chance encounter in Vienna brought the last key witness in my investigation. During the first week of my stay I met a local journalist and cultural critic Hugo E. I told him about my investigation.

“Yes, the camp on Dreherstrasse,” he said looking into my eyes. “It was an ugly place.”

This was no small talk. The man did his civil service there in 1985 when it became again an office of the Red Cross. We remembered together cracks in the concrete wall with the barbed wire, anonymous hospital rooms, a yard with sickly trees.

“Have you ever asked what was there before? I prodded.

“No. In Vienna, we don’t do that,” he said quietly.

He drew a picture on a napkin of the narrow bunk bed with broken springs that left scars on his body. There was something else there that haunted him even more than those springs: the empty forms and signs written in Cyrillic, the instructions that he couldn’t understand. Unreadable, they became the stuff of his dreams. By 1985-86 the former transit camp ceased to exist, as emigration from the Soviet Union fizzled to a minimum. That stained napkin with the drawing of springs protruding from the bunk beds might have been the last afterimage of our unphotographed transit.

On a sunny wintry day in January 2012 I returned to my camp. From the window of the old car I got an oblique glimpse of the village church and lacy curtains on the dark windows, evocative as they were unrevealing. The journey felt like a road movie with long takes and no denouement.

“Sorry, there is not much here,” said my Viennese friend who drove me to Simmering. He left me alone to wander along the deserted Dreherstrasse. The main building that housed the camp hadn’t survived, but the territory did, complete with fences, warehouses, packaging from recycling machines, archives of trash. I found there a shopping cart filled with evergreen pinecones, a moving altar to an emigrant genius loci.

In 2006 a part of the former camp territory had been developed into a project of ecological housing. The new buildings bore the names of exotic fruits in Italian Melanzana, Pera, Melone, turning the history of the site into a delicious pastoral. The new buildings were surrounded by an ecologically designed fence behind which was an abandoned territory with high grass, weeds, and withered flowers growing next to the thick concrete wall circa 1970. There was still occasional barbed wire visible and rusting remains of the old infrastructure for the security cameras. Between the ecological fence and the concrete walls of the former camp, Simmering teenagers were playing a ball game, oblivious to the past and the future, the way teens are.

The adults were not so different. Nobody working or living on the site had any knowledge of what was there before. “A military hospital? A monastery? Something like that.” I was stopped and questioned once I took out my camera. I quickly excused myself, claiming to be an architectural photographer interested in the former Carmelite monastery. The owner of the ecological project’s new lighting design firm politely invited me in and guided me through his recently redesigned interiors made to “evoke some history.” The office had a nice retro feel of the mid-century Modern style with a few historicist echoes. It still preserved those unusually shaped windows recalled by Constantin. Once again I was struck by the intimate proximity of the refugee camp and the ordinary residences of Simmering; yet even in memory they occupied non-contiguous and incommensurable spaces of experience. I was tempted to tell the retro-loving designer that his office was in a former camp, but I was afraid that he might ruin the memory card in my camera. memory card.

Did I recognize anything when I revisited the camp territory? To be honest, no new reminiscence came to me, no taste of a sweet bread soaked in the camp tea, could breach my forgetting. Yet photographing the former camp territory was strangely ecstatic. It felt like quenching an old thirst. It wasn’t for the sake of recovered memory or history—just for its own sake.

Upon my arrival back in Boston, I found myself staring at the images of the camp, rescuing and highlighting the cracks in the wall.

Everything I photographed all over the world was there: the stains on the concrete walls, sickly poppy flowers and dandelions, half-readable signs, the pinecones in a disowned shopping cart, and a dove, the color of urban ruins, finishing her comfort food, in haste. Wandering through the invisible ruins of the camp I discovered the landscape of my own photographs that traveled with me from one continent to another.

I didn’t know until then that I had been a subject of my photographs and not just a photographer. I stumbled upon an uncharted emotional geography mapped over the inconvenient history. Somehow the walls of the camp stood both for liberation and for confinement, for memory and for forgetting; they became a canvas for our improbable hopes.

After many turns and returns I recognized my point of departure. It was not my house in Leningrad but this forgotten refugee camp that I carried with me as I traveled light. Unmemorable and unmonumental, the camp became a ruin in reverse, a palimpsest of my future transits, a hidden backdrop of my second home.

T.S Eliot described such departure in his Fourth Quartet:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

***

Sign Up for special curated mailings of the best longform content from Tablet Magazine.

Svetlana Boym, the Curt Hugo Reisinger Professor of Slavic and Comparative Literatures at Harvard University, is a writer and an artist. She is the author of The Future of Nostalgia, Another Freedom: The Alternative History of an Idea, a play The Woman Who Shot Lenin, and a novel Ninochka. She is working on a film based on the story of her refugee camp.