Jewish Sexual Pathology, Islamist Terror, and the Collapse of the West at Cannes

The French film festival goes raw on depictions of incest, murder, DSK, Ukraine, Timbuktu, and stardom

War and its corresponding sexual pathologies were the major themes of this year’s program at Cannes, a connection that seems understandable enough if you glance at the newspapers. The vengeful passions of nationalism are staging an unmistakable comeback, even as solemn preparations for the 100th anniversary of World War I take place across Europe. Having concluded their duty as hosts to the film world’s most cosmopolitan film festival with their usual élan, the French stumbled to the polls the next morning to give 25 percent of their vote to the Front National.

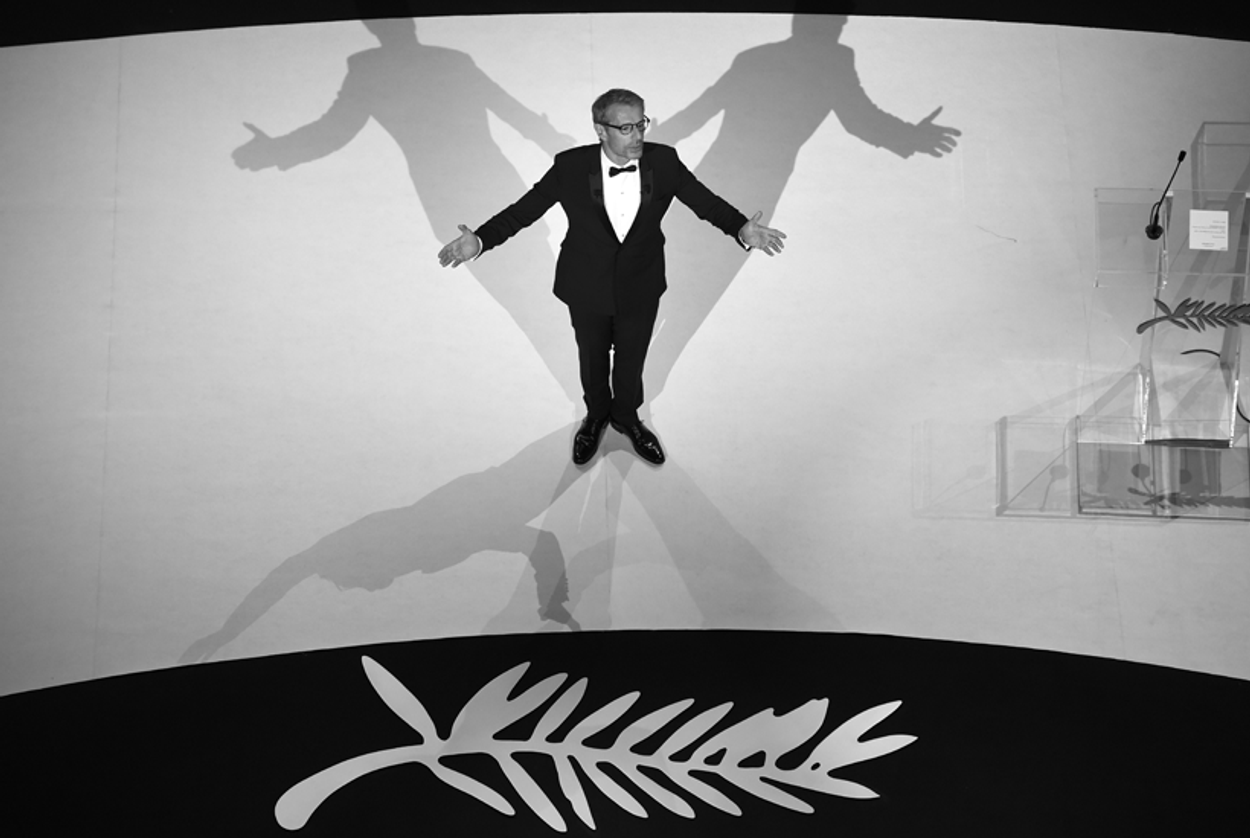

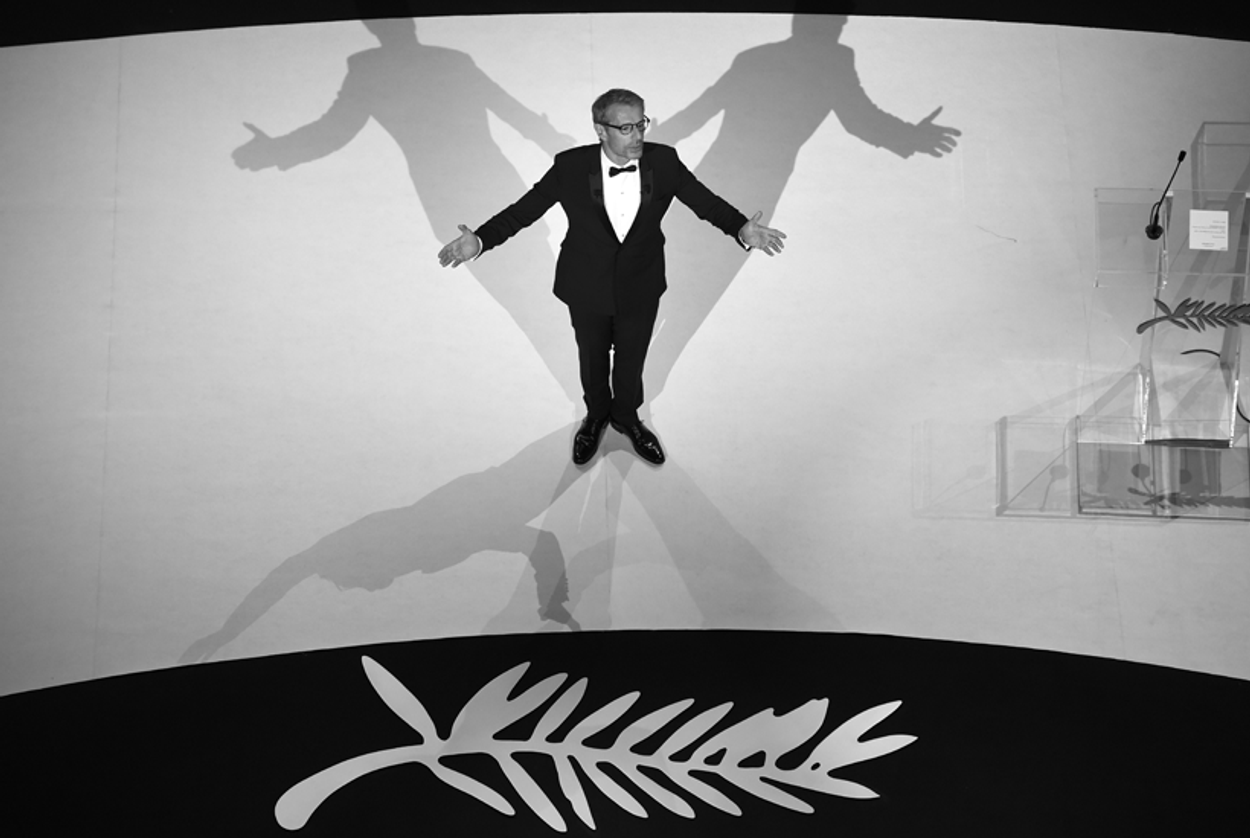

The Palme d’Or went to Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Winter Sleep, a three-hour portrait of the intricate social relations of an Anatolian hotelier providing the beleaguered Turks with some much needed pride and succor. Slated to be this year’s guests of honor in celebration of the centennial of Turkish Cinema, the delegation was forced to call off the lavish parties and receptions after a catastrophic mine collapse in Eastern Turkey buried hundreds of miners alive, plunging the country into spasms of mourning that culminated in a paralyzing political crisis. The flag at the Turkish pavilion flew at half-mast for the duration of the festival.

The Jewish Argentine Damián Szifron’s Relatos Salvajes (Wild Tales) claimed the honor of being the year’s quirkiest entry. A kaleidoscopic portmanteau of six interwoven tales in the comic-perverse vein of Pedro Almodóvar (the film was produced by the Almodóvar brothers, and Szifron is often described as Pedro’s protégé), Relatos is composed of a series of thematically linked fantasias of violence and revenge. In each of the narrative-tales something snaps in a habitually cheated and wronged protagonist—the provocations run the gamut from infidelity to road rage—triggering a cascade of flailing and anarchic anger. Each of the six segments concludes with baroque forms of retribution. Whimsical catharsis is extracted from careening violence as well as the continually recurring trope of glass being smashed into shards. Windowpanes and mirrors as well as drinking flutes are smashed and shattered with gusto.

Szifron’s film is delectable in its way of wringing populist farce and satire out of very South American forms of physical debasement and chicanery. The denouement of the final segment arrives with a carnivalesque Jewish wedding being torn to shreds by an aggrieved bride who is betrayed on her wedding night. This was the festival’s most radically surprising and most beloved moment. After the film ended the caffeinated crowd of critics at the morning press screening howled their applause.

***

After several underwhelming films, David Cronenberg, the Billy Wilder of a darker, less heroic America, returned to form with Maps to the Stars, a deeply contemptuous and impeccably sadistic Hollywood satire. Based on a script adapted from Bruce Wagner’s novel, it skewers the vapidity of Hollywood ruthlessness, status anxiety, and superficiality. The Hollywood subversion send-up has morphed into an acutely conventional genre where, as in much of life, execution is everything. A sweetly odd schizophrenic burn victim Agatha Weiss, played by Mia Wasikowska, arrives asleep on a Greyhound bus. Long gloves cover her scorched arms but do not protect her from her dreams. An ingénue amongst the vipers, she does not imbibe the lesson, that no one in this vile town is to be trusted, quickly and thoroughly enough. The handsome limo driver, an aspiring actor who squires her around, is less intrigued than she is but eventually begins sleeping with her for “research.” Mysteriously she eschews his usual celebrity tour, “the map to the stars,” requesting that on her first foray into the city she be taken to the remains of the burned-out house of the Weiss family. Agatha has befriended Carrie Fisher over Twitter; she in turn fobs her off on the aging diva Havana Segrand (Julianne Moore, selected as best actress at Cannes for her performance), a prototypically neurotic Norma Desmond avatar who is frantic to be cast playing the role of her mother, a 1950s film star immolated in a freak fire, in the remake of the film that had earned her mother her fame.

The Weisses are a family of gorgons whose television pop-psychiatrist patriarch, Dr. Stafford Weiss (John Cusack) hides his malicious persona under a New Age-y façade. Under Weiss’ disturbing ministrations—body massages to channel the “magic child”—Havana recovers long-repressed childhood memories of abuse at the hands of the mother that she is so desperate to inhabit on screen. She also begins experiencing hallucinations. Havana interviews Agatha for the role of her assistant, and, succumbing to the pull of superstition, hires her. Agatha becomes the assistant “chore whore,” which sounds exactly as bad as it is. In one of the most biting images in a film brimming with them, the shy Agatha is forced to discuss her sexual liaisons with the limo-driving actor while Moore’s character defecates on the toilet.

Agatha’s younger brother Benjie is the 13-year-old film star of a lucrative movie franchise called “Bad Babysitter.” The grotesquely spoiled child actor is another Hollywood archetype, but Benjie’s case is salvaged by the impressively nasty wit of the dialogue Wagner provides. His mother Olivia spoils him by satisfying his every whiny desire—whininess will turn out to be the film’s cardinal sin. In the midst of puberty he has internalized the corporate mentality of the culture around him and has already been in and out of rehab. Coerced into a mandatory meeting with studio executives to demonstrate his dependability, he vomits in disgust in the bathroom afterwards. On a Make-A-Wish Foundation hospital visit to a little girl dying of cancer, he is mistakenly told she has AIDS. Leaving the ward Benjie lashes out at his publicist with an expletive-laced anti-Semitic rant. The point being made here is that the publicist’s conditioned obsequiousness is more obscene than the star’s bigoted cursing.

Agatha turns out to be a specter from the past, a harbinger and repository of gruesome family secrets. After having her shipped away as a little girl to a juvenile detention center in Florida—she heeded the voice’s commands and ignited the conflagration of the family home, which scarred her—Olivia and Stafford had long repressed the innate knowledge of her impending return. When they discover that she has returned they take futile precautions to keep her away from Benjie. Benjie and Agatha are drawn to each other by irresistible forces. Sweet Agatha just wants to be reunited with her family. For them she is the recurring symbol of the re-materialization of deeply submerged secrets as well as the supernatural psychosis that binds this family together: the macabre undercurrents and supernatural mysticism that are the authentically dark counterpart to Stafford’s lightly-worn New Age spirituality.

The Cronenbergian culmination of this moral squalor comes through a cleansing cycle of death and salubrious killing. Havana’s rival for the film role of her mother pulls out of filming after her child dies in a freak swimming-pool accident. Upon hearing the news, the exhilarated Havana prances around the room with Agatha chanting “We’re fire, they’re water!” Benjie has a psychotic episode and attempts to choke his 8-year-old co-star to death. Out of the second-floor window of the mansion, a blank-faced Agatha watches the needy and competitive Havana having sex with her actor boyfriend in the back of his limo. When in the next scene Havana begins haranguing the near catatonic Agatha for leaving a trail of menstrual blood along the couch, the girl’s fragile composure shatters. Agatha bludgeons Havana to death with the statuette of a film trophy that Havana covets so badly. Olivia immolates herself and flings herself into the family mansion’s pool. Taking their parents’ wedding bands Benjie and Agatha travel back to the charred site of their old family home to close the circle and symbolically re-enact the wedding of their parents under the moonlight.

The “map to the stars” turns out to be an ancient one; much older than what is implied by the film’s title. The biblical woe of preordained madness that is visited upon Agatha, Benjie, and Havana is a form of higher reckoning with the original sexual sins of the fathers.

***

Surreally enough, Cronenberg’s Maps to the Stars was not even the most disturbing incest-themed film featured at this year’s Cannes. That indelible distinction belongs to Israeli feminist Keren Yedaya’s That Lovely Girl. Set in a claustrophobic Tel Aviv apartment, it is a wrenching realist portrait of 22-year-old Tamia’s incestuous relationship with her father Moishe. A petrifying (several critics have already monopolized the usage of “harrowing”) portrait of sexual, physical, and psychological abuse, it is not meant for the weak of heart or stomach. Tamia is completely servile to her father, complicit in her own domination, cooking and cleaning her prison cell while her warden is away at work. Upon his return he subjects her to beatings, harangues her about her weight, and rapes her in frames that are shot at a close distance by a dispassionate camera.

However sickening, it is nonetheless a romance of sorts: She is as attached to him as much as she loathes him. The bulimic, isolated Tamia inflicts self-mutilation and purgation on herself and the scenes of her binging and cutting herself are repetitive and nauseating. The accretion of pain and humiliation is intended to serve the unhurried narrative, as she begins tentatively groping for a way out of her dependence. Eventually, the monstrous father begins spending time with another woman and flaunting the fact to a despairing Tamia, who finally begins taking furtive movements toward escape.

A decade ago Yedaya won the Caméra d’Or in the Quinzaine des Réalisateurs (Directors’ Fortnight) section for her equally grim Or (My Treasure), which was a disparaging depiction of a prostitute and her teenage daughter in the grip of poverty and (self-imposed) sexual brutality. Some critics took issue with what they saw as the film’s ideological stance overpowering the responsibility to compose a nuanced portrayal of its protagonist’s motives. The rendering of protracted violence unleashed upon the female body skirted along the edge of extracting pleasure from physiological cruelty. This was a mechanistic reduction of the female subject to the level of a symptom, a cipher of victimhood lacking all agency. To some, the gratuitousness seemed more like a moralizing reprimand of the women’s criminal self-debasement than a sincere (or humane) attempt to appraise (or understand) the effects of sinister social forces. If true, that would mean that on occasion the heralded “female gaze” can be far chillier and less merciful a catalystof objectification than the male equivalent it was meant to supplant. This would be a manifestation of the purist impulses to revel in the caged entrapment of the weak, to decline pointing out the emancipating gap between the bars, and to declare oneself the whole time a simple expositor of the evils of involuntary confinement. In short, a good working definition of sadism. I cannot say for sure if this is also the case of That Lovely Girl, as I could not force myself to watch the film to the very end.

***

Of course, no dispatch on the theme of sexual pathology at Cannes would be complete sans a guest appearance by disgraced finance minister and former IMF head Dominique Strauss-Kahn. Readers with a long memory might recall that it was during the midst of the festival’s 2011 iteration that the world learned of the rape allegations leveled against Strauss-Kahn by a New York City Sofitel maid. DSK, as he came to be known, then chose a red-carpet premiere at last year’s festival, Jim Jarmuch’s stylized vampire romance Only Lovers Left Alive, as the backdrop of a fiendishly dramatic return to French public life.

The hotel incident that quashed Strauss-Kahn’s presidential ambitions may have been far too Greek in titanic hubris to avoid cinematic rendition. Three years later we find ourselves proffered Bronx-born Abel Ferrara’s Welcome to New York, a tragic-comedy of botched execution. The film stars formerly French Gérard Depardieu, now a Russian citizen and patriot, as a wealthy and powerful central banker with a penchant for orgies. The preternaturally sly euphemism “lightly fictionalized account” has been much used in describing the proceedings, and Welcome to New York was not selected by the jury for screening in any of the festival’s myriad programs. The premiere in (rather than at) Cannes took place outside of the festival strictures in a private screening at a cinema along the Rue d’Antibes.

The producers’ insinuating allegations of a campaign of politicized censorship directed at the film by an insular cabal of elites surrounding Strauss-Kahn begin to look somewhat forced if one takes into account the trifling issue of the film’s quality. (It was simultaneously released online via an unorthodox video-on-demand scheme throughout Europe and is allegedly set for a limited American theatrical release later this year.) Invites to the suitably decadent post-premiere beach party were the festival’s most coveted commodity. Reportedly (this critic did not attend), sexual paraphernalia, Viagra, and monogrammed bathrobes were given out as party favors while dancers dressed as nurses squirted alcohol out of syringes down people’s throats.

All the smart French critics and savvy media types I spoke to about the film dismissed it out of hand on artistic grounds, but most were impressed with the artistry of its marketing campaign. The same thing cannot be said on behalf of Strauss-Kahn, who promptly sued for libel and defamation. This was to be his second lawsuit since March, when he sued novelist Régis Jauffret for the novel The Ballad of Rikers Island, which featured a wealthy and powerful central banker with a penchant for orgies.

Reportedly, sexual paraphernalia, Viagra, and monogrammed bathrobes were given out.

The allegations of anti-Semitism in the profane, grubby, and lecherous portrayal of “Mr. Devereaux” are plausible enough. Strauss-Kahn’s lawyer during a radio appearance compared the film to a “dog turd, that one would ordinarily sidestep.” Yet even that expurgation was to be topped by the acid judgments of Strauss-Kahn’s ex-wife, the heiress and prominent French TV journalist Anne Sinclair. Sinclair concluded her brief article on the affair with “Je n’attaque pas la saleté, je la vomis”—“I don’t attack filth, I vomit it.” On Sunday after the festival, the New York Times would lecture us on the finer points of “Why DSK won’t go away.”

***

Half the globe away from the narcissistic and petty skirmishing among competing factions of the French élite, the world was aflame with more consequential cases of pathological frenzy. A global orgy of violence and communal intolerance threatened the annihilation of civilization in the places where it was oldest and most fragile, a development that was noted here in an unprecedented number of war films and documentaries. That many are set in the Islamic world shows us how quickly globalization has sanctioned the production of world-class cinema in places where cameras are new, as well as how the aggressive impulses of the discontented to make war, and the revulsion and backlash to it, are being rapidly globalized. The Mauritanian-born (he was raised in Mali, educated at Moscow’s fabled VGIK film school and residing in France) director Abderrahmane Sissako’s Timbuktu is particularly masterful and subtle. It is an indictment of the spiritual and physical destruction of Timbuktu’s cultural heritage by sinister and occasionally hapless outsiders. It was an early favorite for the Palme d’Or and that it received no festival prizes borders on the criminal.

Set in the ancient citadel during the early days of the 2012 invasion of the mellow capital by Islamic fundamentalists (hints are scattered throughout that this was an unexpected outcome of the collapse of Qaddafi’s Libya), the film opens with a desert scene of jihadists riding in a flatbed truck while taking potshots at traditional masks and religious artifacts with a machine gun. The newly arrived jihadists do not speak the local languages but are ruthless in enforcing prohibitions against traditional music, sports, and women’s rights. The local imam, representing the benevolent and enlightened Islam of the locals, can explain nothing to the dogmatic invaders, but he does shame them into departing from his Mosque while armed.

It is partly the jihadist’s sexual repression, the film intimates, that leads to the fundamentalist interpretations of Sharia law—women are lashed for sitting unchaperoned with men, and an unmarried couple is buried up to their necks and stoned to death. After being spurned by a potential bride’s family, the jihadist returns to take her by force, and a justificatory bit of Quranic scripture is readily found as pretext. When the jihadist leader Abdelkrim arrives at the tent of a family of Tuareg nomads to try to convince autonomous Satima to cover her head, his gaze betrays his longing and she points out that “she is a married woman and that he should not come around when her husband Kidane is gone.”

Kidane, a nomadic cattle herder, loses a cow named “GPS”—Mali too is drifting. The cow is caught in the fisherman Amadou’s nets, and he kills it with a graceful toss of his spear. Kidane arrives to discuss the matter and when the two begin to wrestle in the shallow waters, the pistol in his pocket discharges, accidentally killing the fisherman. The ochre-hued palette and iridescent glimmer of the fisherman’s death scene are shot from afar with a wide lens, and it is unforgettable. The innocent Kidane’s punishment by Sharia law will be pronounced promptly by a foreign judge who needs an interpreter when he dispenses judgment.

If the beautifully shot and stylized political violence in Timbuktu, which proceeds according to internally cohesive aesthetic predicates, leaves one uncomfortably mesmerized, then Eau Argentée, Syrie Autoportrait (Silvered Water, Syria Self-Portrait), by the exiled Syrian filmmaker Ossama Mohammed, will simply horrify. The film shows us the effects of a more singularly substantial assault against the structures of civilization. The film is stitched together from 1,001 bits of amateur video and grainy cellphone clips taken off of YouTube. The visceral, even unspeakable brutality of the film—we watch men die from summary executions, running crowds are machine-gunned, cameras are stuck inside festering sniper wounds to the head, and we watch authentic footage of a teenage boy being beaten and anally raped with a baton in a prison cell—calls for a reiteration of the caveat, not meant for the weak of heart or of stomach. Mohammed, who moved to Paris in 2011, frames his feelings of loss and survivor’s guilt through a discourse of loss and spatial displacement, an overwrought form of poeticized commentary, and letters to his girlfriend. This is no doubt a cultural form and a civilizational narrative norm and is certainly a matter of taste. For myself I found it to be a manifestation of insufferable treacle, and I imagine that many other people might as well. After the screening one is liable to feel the oncoming symptoms of PTSD.

***

Sergei Loznitsa’s Maidan narrates the key events in the three-month-long encamped protests at Kiev’s Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square) that brought down the kleptocratic regime of Pro-Russian President Victor Yanukovich in February. Classified as a “special screening” and eagerly awaited by both politicos and cineastes, it was a prominent feature in the program. Belorussian-born Loznitsa was raised in Kiev and is currently Ukraine’s most celebrated filmmaker. (This is of course not counting national treasure Kira Muratova, who will be turning 80 years old this year in Odessa.) Maidan is Loznitsa’s third film and the first since 2012’s hazily ruminative WWII occupation drama V Tumane (In the Fog). That film interrogated friendship, complicity, and collective memory, and one only wishes that more people in the West had gotten a chance to watch it. Loznitsa suspended production work on his forthcoming film about the Nazi massacres at Babi Yar in Kiev to spend time filming the demonstrations.

The selection of his film for inclusion in Cannes from among all the innumerable existing and imminent Maidan documentaries might at first glance seem to be a rather unimaginative choice. For this critic personally, any lingering apprehensions about whether the film would have been programmed under another director’s name were quickly defused by an appreciation of the former mathematician’s meticulous adhesion to formalist constraints.

Employing tricks and visual vocabulary borrowed from Russian Formalism as well as the shot compositions of the crowd scenes from Sergei Eisenstein’s Strike (1925), Loznitsa purposefully placed cameras around the periphery of the Maidan. The resulting static frame envelopes the viewer in broadly composed and openly apportioned spaces. The film commences with a wide shot of the activists’ stirring rendition of the Ukrainian national anthem, and then the camera follows the fraternal spirit of total mobilization that sprang up in the Maidan in the midst of the December frost. We watch the bustle of political activity—jovial speeches, public poetry recitals, festive organizational meetings—as well as the veritable anthill of domestic activity that developed spontaneously to help with the upkeep of the city-within-a city. The crowd moves in and out of view of the screen, following its own inscrutable logic. Men drape themselves in flags, and volunteers brew tea and ferry sandwiches. The young build barricades while babushkas ladle soup.

Each of the film’s segments is about five to 10 minutes in length and depending on one’s tastes is either mesmerizingly or agonizingly slow. A few minimalist black titles provide basic information: With parliament’s introduction of a batch of repressive anti-protest laws on Jan. 19, the women, children, and babushkas all suddenly disappear, to be replaced by men dressed in secondhand army fatigues and gas masks. Bonfires and piles of sandbags replace the boxes and detritus of the original fortifications. Clashes begin to erupt as packs of demonstrators glide gracefully in and out of our sightline to let loose rhythmic volleys of cobblestones against the metal of the shields of the detested Berkut riot police. Segment by segment, and day by day, we watch the ratcheting up of the conflict. Skirmishes turn into bloody battles as the protesters exchange cobblestones for Molotov cocktails. The Berkut graduate from batons to water cannon, to teargas grenades, and finally to rubber bullets. Civil war has broken out in the central streets of Kiev.

The camera’s one capitulation against the film’s core constraint of immobility comes when the cameraman is bombarded by teargas canisters and must flee along with the rest of the crowd. By the time of Feb. 19 segment (when the demonstrators marched on parliament), the interior ministry troops are called in and given criminal orders. The camera’s vantage point is shifted to a bird’s-eye view, and we find ourselves perched above the action on a hill. This scene is founded on the widest shot of the whole film, and in the distant right corner of the screen we see the columns of Berkut and interior ministry troops firing into the crowd with shotguns and Kalashnikov rifles. Wafting ethereally from a loudspeaker is the voice of an unflappable demonstrator appealing for reinforcements to be sent to one street and for ambulances to another: At this point we feel ourselves to be in the center of the carnage viscerally, of a sniper nest on the top floor of the Hotel Ukraina. We are appealed to converge at the makeshift operating room set up in the trade union building if we have medical training. “We have pushed the Berkut back into the park along Grushevskaya street, we have our first tactical victory!”

After a slow blackout, we are given scenes of the crowd weeping and mourning. In a funeral scene set at night and illuminated by candles and cellular phones, the caskets of the “heavenly hundred”—the hundred activists killed in the bloodbath—are passed over the heads of the crowd. The film ends with a haunting rendition of the folk ballad “Plyve kacha po tysyni,” which concerns a young Ukrainian soldier asking his mother what will happen if he dies in a foreign land.

The former French foreign minister and storied humanitarian interventionist Bernard Kouchner attended the press screening of the film and sat with me chatting about the politics of the upcoming election (we had both flown into Cannes from Kiev after attending the New Republic’s “Ukraine: Thinking Together” solidarity conference several days earlier). Mr. Kouchner was visibly entranced at the conclusion of the film’s screening: “At the beginning, the movie is a bit slow and boring,” he told me. “But after that it becomes remarkable. The director does not comment, he shows the crowd to be one organism.”

After the screening, journalists and onlookers crowded into the terraced back yard of the Ukrainian pavilion for Maidan’s press conference. The plucky staff of the Ukrainian pavilion had brought gas masks and a miniature reproduction of the Maidan Christmas tree from Kiev and decorated it with a nationalist flair. With a week to go before presidential elections that would elevate chocolate magnate Petro Poroshenko to the presidency, Ukraine’s guests were treated to handfuls of his Roshen chocolate. After the standard questions about the film were fielded, a journalist for the Russian opposition TV channel Dozhd (Rain) inquired why Loznitsa was boycotting the Russian media or press, even very liberal ones (on the verge of being closed down) such as themselves. Loznitza replied to the effect that there was so much disinformation and propaganda being bandied about the Russian media sphere that he simply did not want to be involved. The journalist did not look satisfied with the explanation for the boycott.

The director wrapped up the conference with a pledge to upload the film to the Internet, after a brief theatrical release, so that the movie could be seen by everyone who might not otherwise have access. The final riposte was bellowed from the back of the overflowing crowd. “Sergei Vladimirovich!” a middle-aged woman from Russia called out. “You should do that quickly! While there is still an Internet in some countries!”

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Vladislav Davidzon, the Chief Editor of The Odessa Review, is a Russian-American writer, translator, and critic. He was born in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, and lives in Paris.

Vladislav Davidzon is Tablet’s European culture correspondent and a Ukrainian-American writer, translator, and critic. He is the Chief Editor of The Odessa Review and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Atlantic Council. He was born in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, and lives in Paris.