A Cannes Diary

Tablet’s European culture critic sends daily dispatches from this year’s socially distanced Cannes Film Festival

Despite all the theatricality of arriving here, the myriad travel bans, and the horrible need to produce a gallon of saliva for a COVID test every 48 hours (authorities detected an average of three or four cases a day), the Cannes Film Festival somehow persevered and concluded mostly without incident. The business of film and glamour in the south of France went ahead despite everything. Now, the prizes have been awarded, the beach clubs emptied, the red carpets rolled up, and the black bowties untied. So, fellow citizens of the Republique of Cinema, what have we learned?

With COVID being quite enough, the festival noticeably avoided any ancillary scandals this year, having mostly moved on from the blowback to the Harvey Weinstein-inspired sexual harassment scandals which had dominated 2019. As usual, however, lots of people were unhappy with the allocation of awards.

Iranian director Asghar Farhadi’s Ghahreman (A Hero) split the second (Grand Prix) prize with Juho Kuosmanen’s HYTTI N°6 (Compartment N°6). The Iranian film had been much liked by the critics and was expected to do well, while the Finnish-Russian train trip movie was an unexpected choice. Farhadi was criticized for not delivering a statement about the political situation in his home country while accepting the award. Unlike Eurovision, where political talk is banned, at Cannes, political gestures at the ceremony are par for the course.

Leos Carax took home the best director award for his fittingly disturbing Annette, which had also opened the festival. That had been widely expected. The beautifully shot Thai film Memoria, which had Apichatpong Weerasethakul directing Tilda Swinton in soporific fashion, tied with Nadav Lapid’s anti-Israeli screed Ahed’s Knee for the Jury Prize. In my opinion, not only has Lapid made better films in the past, watching both of those movies was sort of a chore. It should also be added that both films garnered fairly low aggregate scores in the daily rankings published by the free print glossy weeklies (Variety, Cannes Gala, etc.) that are given away everywhere at the festival.

Sergei Loznitsa’s Babi Yar: Context, a critically important historical film that I reviewed earlier in my diary, won the Golden Eye Award for documentary. The Russian director Ilya Khrazhanovsky accepted the award in Loznitsa’s place after he had left the festival, raising the prize over his head in triumph. Hopefully, receiving this award will ensure that this film is widely seen.

On Saturday evening, Julia Ducournau’s Titane—glitzy, flashy, and fleshy serial killer pulp—received the Palme d’Or Festival top prize. Spike Lee, the head of the jury whose head could be seen strewn all over town on the festival posters, revealed the victory accidentally ahead of schedule at the ceremony, to the sound of audible gasps. It was somewhat fitting that Spike flubbed his line for a film that many film purists attending the festival considered to be unworthy of the honor. Inveterate festivalgoer and my fellow Tablet contributor A.J. Goldmann, a deeply penetrating and erudite critic who I see several times a year at festivals, was flabbergasted that the film received the Palme d’Or. “Titane is slick trash masquerading as high art. Its Palme d’Or win represents the vacuous triumph of fanboy and fangirl sensibilities as well as the lurid, gratuitous violence that saturates contemporary pop culture. It is the apotheosis of bad taste,” he pronounced.

Hopefully the prize will go to a more worthy contender at the 2022 festival. See you next year on the beach!

The Cannes Film Festival of the plague year is beginning to wind down. This festival, which heroically (or perhaps madly?) returned to business as usual, despite the obvious impediments, will surely be remembered for years to come. If COVID is not going to be eventually conquered by modern science and universal inoculation, the sanitary innovations premiered here will surely become standard practice in festivals and large-scale convention events for the years to come.

The relocation of the festival from its habitual May dates had both positive and negative effects. One can swim this year and the water is perfect. On the other hand, wearing a tuxedo all day in the summer sun can be horrific. My journalist comrades were all giddy that the festival had finally instituted a proper ticket system instead of having people wait for hours in their formalwear in the sun. Everyone hopes this sanity-preserving system will be kept if normalcy ever returns here.

Despite itself, the outside world encroached on the hermetic inner life of the festival. When the Italian team won the European football championship, the Italians drove up and down the seaside town yelping with pride, the national flag draped over their cars. The Bastille Day fireworks, fired from barges anchored off the coast, bloomed over the Croisette. The seaside was no less full of jostling crowds of locals and tourists than usual. In some ways, it was possible to forget that we were in the midst of a worldwide pandemic. My own personal favorite private evening of the festival was at the beach party thrown by the Ukrainian Embassy: My Ukrainian producer wife, Regina Maryanovska-Davidzon, and the former Ukrainian first lady Kateryna Yushchenko both showed up in orange (revolution) dresses.

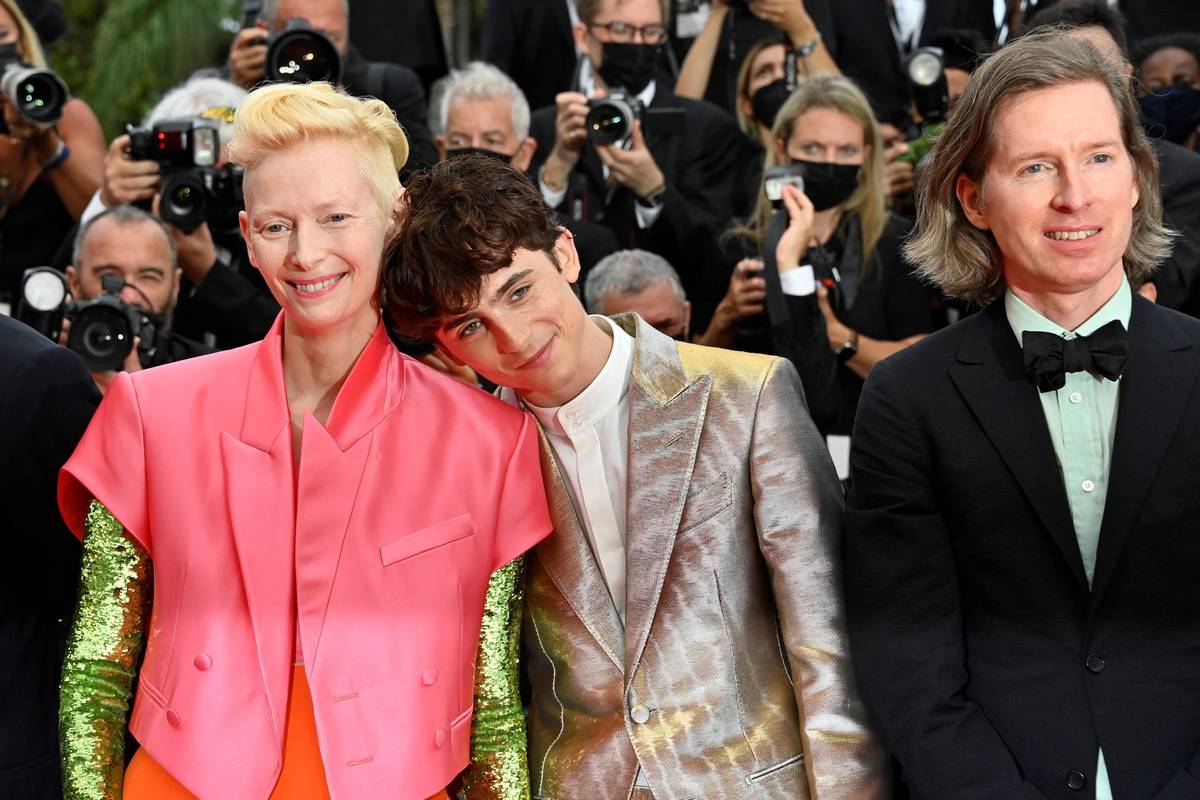

This year, Tilda Swinton seemed to be everywhere. In fact, she appeared in five films, which is possibly some sort of record. The actress could be seen on the red carpet continually and flew past me at the Majestic hotel as I was having lunch with the Russian publisher of The Art Newspaper, walking with an intense purposeful stride and wearing a pair of bright blue silk trousers. In real life (if Cannes can be said to be anything of the sort) Swinton possessed the same sort of ethereal aura that she does in her films. She played it cool in Thai director Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Memoria and hammed it up in Wes Anderson’s exuberant The French Dispatch (what a fantastic and fun film that is, by the way!) The red carpet photo call snapshot of Bill Murray, Tilda Swinton, Wes Anderson, and Timothee Chalamet hawking The French Dispatch lit up the social media sites. Incidentally, if Anderson is reading this, I continue to patiently await the call to be cast in your next film in whatever role I am needed in.

In Joanna Hogg’s semi-autobiographical The Souvenir Part II, Swinton acts alongside her own daughter Honor Swinton Byrne, who returns in the role of film student Julia. The 23-year-old grieves her drug addict boyfriend after he overdoses. Playing Rosalind, Swinton comforts her daughter as she tries to make sense of his sudden death. The film is set in the London Underground and within the film scene of the 1980s. I found the movie to be likable enough in a placid fashion, but my friend Peter Webber, the director of The Girl with the Pearl Earring, disagreed when we discussed the film. “I lived through the early 1980s in London, which was a time filled with anomie and heroin, and there is very little to be nostalgic about. For some people this is a fascinating period piece and for others this is like seeing the ghosts of the past resurrected!” Webber quipped over a glass at the Cafe Roma.

Russian cinema is having an excellent year on the Côte d’Azur. Despite the severity of the COVID epidemic sweeping through Russia, and the subsequent difficulty of traveling through Europe, this year’s festival enjoyed a large contingent of Russian attendees. At the beach party premiere of the Ukrainian filmmaker Sergei Loznitsa’s Babyn Yar, Context, one could run into Russian film luminaries such as directors Ilya Khrazhanovsky and Vera Krichevskaya. The Russian journalist Mikhail Zygar could be seen speaking with Arkady Ostrovsky, The Economist’s Russia editor. The puckish Khrazhanovsky and I spent two hours poolside at the bar of the Majestic discussing the success of the Loznitsa film and his plans for the Babi Yar Holocaust Memorial Center (Performance artist Marina Abramović will be arriving in Kyiv at the end of the month to begin work on her art installation there.

Moreover, three Russian films and a Finnish road trip film set in Russia were included in this year’s festival competition. The Finnish film Compartment No. 6 (a Finnish-German-Estonian-Russian co-production helmed by veteran director Juho Kuosmanen) observes a young Finnish student trekking through Siberia on the Moscow-to-Murmansk express. It is a late ’90s phantasmagoria. Appropriately enough, she is fleeing from a stalker.

Unclenching Fists is the other Russian film dealing with the theme of a young woman’s autonomy in the Cannes competition. It is the first Cannes appearance for the up-and-coming Russian filmmaker Kira Kovalenko. Set in a mountainous village in the Caucasus, in Mizur, North Ossetia, the film observes a claustrophobic family dynamic revolving around a patriarchal elder, who refuses to grant freedom to his children, thus allowing them to grow up. The protagonist of the film is a young woman, Ada, on the cusp of adulthood. Ada is being pursued by a boy (who she also likes) and has a younger brother who keeps her in line on behalf of the totalitarian whims of their father. An older brother has already left this hothouse atmosphere for the Russian city of Rostov-on-Don. The arrangement is highly repressive and sexually charged.

In almost every manner of style and thematics, the film is remarkably similar to Kantemir Balagov’s 2017 drama Closeness, though this may not be terribly surprising as Balagov is known to be Kovolenko’s boyfriend. Closeness also followed a story of patriarchy, sexual and social repression in the Caucasus—in that case, the daughter of a Juhuro Mountain Jew clan who was involved with a local boy. That film was also distinctive for featuring a snuff film version of the killing of Russian soldiers by Chechen militants during the first Chechen war. In both films, the core question raised by this genre is whether the young woman in question should follow the path of traditional custom, or break away from her family and seek a modern path.

Additionally, theater director Kirill Serebrennikov has returned to Cannes with Petrov’s Flu, his surrealist satire of the mordancy of Russian life. The film is a stylized, Sorokian, postmodern adaptation of a novel by the writer Alexey Salnikov. Delusion, delirium, and violent fantasy are the lines along which this bleak story of personal and social corruption plays out. Like Closeness, the film is set in a deeply provincial corner of Russia, the Ural mountains. Petrov, a mechanic in his late 20s, is suffering from a metaphysically virulent flu whose health effects include overdetermined metaphors for the current COVID epidemic and unreliable, narration-inciting hallucinations. His sickness is indeed horrific, but it also unveils his writerly imaginings—and his capacity for violence. Petrov winds up drinking with a former friend in the back of a funeral hearse, which he takes for a joyride. Naturally enough, he wakes up in the coffin. Meanwhile, his suffering, librarian ex-wife also engages in fantasies of violence, in her case against belligerent men. The imagery and tone are often grotesque and harrowing, yet also compelling and stunning on occasion. But it is hard to see how non-Russians would understand much of the film’s contents.

Serebrennikov, a cause célèbre for the Russian intelligentsia and international media, has recently been released from house arrest in Moscow. For the second time in a row, he was unable to attend the premiere of his film in Cannes, because he still is not allowed to leave Russia. In 2018, he premiered his lovely black-and-white film Leto, which I attended and described in these pages as “a love letter to the early 1980s Russian underground rock scene” and a “lovely and surprisingly accessible work of popular rock filmography.” Petrov’s Flu, too, uses the musical number set piece, a technique that was charming in Leto, but on this occasion the production is rather frightening. When Leto premiered here several years ago, Serebrennikov was being investigated for allegedly embezzled funds from a theater company he headed, and had been placed under house arrest. The case was widely viewed by the liberal Russian opposition and critics of the government as a political prosecution. Serebrennikov is known to have an acrimonious relationship with the government—a former Russian minister of culture in particular. He has since been remanded and is currently carrying out a suspended prison sentence, but he did miss his mother’s funeral during the course of the legal procedures.

This, of course, is why the Russian director Aleksey German Jr.’s festival entry, House Arrest (Delo), which depicts a politicized embezzlement case being waged against an intransigent and troublemaking intellectual, is such a compelling film. Fifty-year-old David (played wonderfully by the actor Merab Ninidze) is a stubborn Georgian professor of Russian literature who lives with his mother. It is hinted by the FSB interrogator, who respects him and is only following orders, that David’s mother is Jewish. A paragon of the outsider liberal intelligentsia, David is hounded by the corrupt mayor of his little town and ultimately sentenced to house arrest. The details of the case parallel Serebrennikov’s real-life plight almost exactly. The film was shot entirely in a disheveled, book-filled apartment, which essentially looks like every place I lived in as a kid. It is linear, humanistic, and much less structurally convoluted than German’s usual high art productions.

Eventually, the state harassment causes David to lose his health and the strain on his mother causes her to have a stroke. He misses his mother’s funeral during the course of the legal proceedings. I really do hope that they continue giving German money to make films after this, but I would not count on it.

The autobiographical film Waltz With Bashir, which Israeli director Ari Folman premiered here at the festival in 2008, was unambiguously a masterpiece. It was an earthquake that shook cinematic history. The autobiographically based protagonist of the film embarks on a poetic quest to recapture his repressed memories of the Lebanon war, and learn the truth about what happened at the Sabra and Shatila massacre in 1982. It is not an exaggeration to say that the film would revolutionize the history of animation.

At the 2013 Cannes Film Festival, Folman premiered The Congress, a fantastically weird and original part-animation film that no one saw or heard of, and which lost a pile of money. The Congress was based on the classic science fiction novel The Futurological Congress by Stanisław Lem, and starred Robin Wright and Harvey Keitel. The fact that no one saw that quirky and very imaginative film is a minor tragedy of contemporary cinematic history. It also likely has something to do with the fact that Folman has not had a new film for almost a decade.

Now, though, he has returned to Cannes with his adaptation of the Anne Frank diary, Where Is Anne Frank? The melding of the iconic material with the exquisitely gifted director is mostly a good match. Folman has done an estimable job of bringing Anne to life without falling into any of the numerous, and obvious, traps that lay in the path of such an adaptation. The plot centers around Anne’s diary literally coming to life in the guise of Kitty—Anne’s imaginary friend to whom the diary was addressed. She arrives in our own time in Amsterdam, bubbling over with positive energy as she escapes from the confines of the Anne Frank House. Does she, and the diary, have a life outside of her physical, spiritual, and moral embalming in a museum visited every year by millions of people? She is here to literally ask us the titular question. What have we learned from Anne’s story?

The film, it should be said, is very charming, sprightly, and lively. The technique melds two distinct animation aesthetics, jumping back and forth between our time and Anne’s in order to make the figure of Anne relatable (a very light pedagogical exercise indeed) to a contemporary audience of tweens and young adults. The film was made in conjunction with the Anne Frank Foundation in Switzerland and clearly has the aim to educate. When Kitty asks Anne why people hate Jews, she explains that people have hated minorities throughout time. This answer is not entirely satisfying, but this is a children’s film after all, and it does meld with the wider philosophical and political themes of the film.

The animation is innovative enough. Anne’s prewar world is depicted by the fantastical carousel of her schoolmate admirers—all of them are in love with her, she exclaims! Kitty eventually steals the actual artifact of the diary—which she requires as a talisman to manifest herself in our reality. She develops an attachment to Peter, a pickpocket who swipes the wallets of the Japanese tourists who visit the Anne Frank House museum in Amsterdam. The romance is intercut with Anne’s real-life flirtation with Peter van Pels (who was remade into Peter van Damm in the diary.) Along with Peter and the diary, Anne goes on the run from the Dutch police, who want to recapture the “greatest artwork that this country has produced since Rembrandt.” The film makes a clear decision to connect Kitty to the plight of African refugees living in Amsterdam, perhaps in an attempt to make the story timely. This choice can be seen, depending on one’s taste or politics, as either extraordinarily daring or a bit on the unsubtle, treacly side.

Nonetheless, the scene of Anne and her family being deported to the East is intense and memorable, with the columns of marching Nazis portrayed as monolithic giant shadow men. The eventual descent into the concentration camps is portrayed as a literal descent into Hades. Where Is Anne Frank? is a relevant historiographical question, and in this film, Folman gives us a possible and worthy answer.

Sergei Loznitsa, who is widely considered to be the most accomplished living Ukrainian film director, has been a Cannes Festival mainstay for many years. He is a particular favorite of the festival director, Thierry Frémaux. His art alternates between highbrow existentialist-themed cinema and formally precise historical documentaries, with the events of the Second World War and the Holocaust constituting a primary theme. In 2012, Loznitsa competed for the Palme d’Or with his chiaroscuro war drama In the Fog, which raised the uncomfortable issue of Soviet collaboration with the Nazi occupiers. His next film, Blockade, focused on the events of the siege of Leningrad, and then five years ago he premiered Austerlitz, a typically astringent and judgment-laden meditation on the practice of Holocaust tourism. In 2018, I reviewed the premiere of his best director prize-winning Eastern Ukraine war film Donbass for Tablet.

In recent years, Loznitsa has more often assembled meticulous documentaries spooled out of historical archive footage, which he arranges in formally interesting and innovative ways. He crafted these expository historical essays about Stalin’s funeral and the 1930s show trials. These films share a particular aesthetic: formally composed shots, a distinctive simmering style, minimal or muffled sound, and long takes accompanied by minimal authorial explication. The films, which constitute a coherent oeuvre, are of wide interest to all post-Soviet citizens.

Loznitsa had long harbored the ambition of making a film about the September 1941 Babi Yar massacre, and he has finally done so. He puts together a powerful historical, and perhaps revolutionary, document in the film Babi Yar: Context.

Composed mostly of footage shot by Nazi and Soviet cameramen, the film consists of materials that have almost never been seen by the public. Much of the action revolves around closeups of seemingly unending columns of prisoners of war. These are the thousands of Red Army young men captured at the start of the Nazi blitzkrieg, and later in the film, when the tides of battle have been reversed, they are haggard-looking Germans. German tank columns roll through the Ukrainian countryside and SS stormtroopers immolate the homes of Ukrainian farmers using flamethrowers. Closeups of the Soviet POWs show men with facial features of every Soviet nationality. Long shots taken from the cockpits of Soviet fighter planes depict seemingly endless fields of wreckage.

The film’s depiction of the capture of the Western Ukrainian city of Lviv/Lemberg by the Nazi forces in the early days of the war is likely to further ignite the historical disputes currently taking place in Ukraine. It is well known to historians (and historically literate members of the public) that the Western Ukrainians—chafing at Soviet occupation and assuming that they would receive autonomy along the model of occupied Croatia—greeted the incoming German army with flowers. They would quickly regret doing so as, over the course of the war, the Nazis were responsible for the deaths of over 5 million non-Jewish Ukrainians, running the gamut from Communists to nationalists. There are pitiless images of the frenzied killing of the Lviv pogrom.

After an interlude, we see Hans Frank, the Nazi governor-general of the occupied Polish territories, being greeted by a brass band visiting the city. The Soviet troops begin to build barricades, preparing to defend Kyiv, and the scene cuts to the aftereffects of the tremendous explosions set off by the retreating Soviets, which leveled the downtown of the city. The title card explains that the Germans had decided to exterminate the Jews of Kyiv in reprisal. Posters of Hitler are put up on every trolley after the city is occupied—they will be torn down an hour later.

The central event of the film, the Babi Yar massacre, represents a strange lacuna at the center of the narrative, as the Germans did all they could to destroy the documentary evidence of their crimes once it became obvious that they would lose the war. There is simply almost nothing to document the actual killings in the ravine. Instead of through film, the massacre is depicted through the few surviving photographs of its aftermath: piles of clothes, strewn bodies, and personal artifacts. There is one shot of a discarded prosthetic limb.

We watch the Soviet army retake Lviv and the victorious Polish and Soviet generals make speeches (in Polish and Russian), with the film firmly intimating that perhaps the locals cheer whoever arrives in the city. An extended montage shows the 1946 public trials of the German SS officers who had taken part in the genocide, including testimony from Jewish survivors of the killing and a scene showing the public hanging of ten German SS troops, which was attended by hundreds of thousands of cheering Soviet citizens. The events of the film span until the mid ’50s, when the Soviet authorities decided to flood the area with toxic runoff waste from a brick factory. The conclusion is that of an excerpt from novelist and journalist Vassily Grossman’s powerful 1943 article “Ukraine Without Jews,” in which he lists all the different sorts of Jews who were killed.

The film was produced and financed in tandem with the Babi Yar Holocaust Memorial Center, and two of the four billionaire funders of the project were in attendance at the projection—as was Russian film director Ilya Khrazhanovsky, the artistic director of the center who is a producer of the film. The sequence of events is quite linear, but many of the scenes would be gnomic to nonexpert audiences. After the film, Father Patrick Desbois, who was in attendance at the premiere, pointed out to me that Loznitsa had made the decision to only show the killings in Lviv and Kyiv, when there were multiple other massacres that he could have focused on. Some viewers of the film were divided on whether a film whose title literally includes the word “context” had actually offered enough of it. Still, the movie is an immensely powerful, precise, and intelligent work of art made by a director fully immersed in both the history of cinema and that of his own lands.

The arrival of the first weekend of the festival has revealed that we had all underestimated its capacity for brute resilience. Especially, as it turns out, in the service of the most blessed causes of Eros and furtive sleaze! The Croisette continues filling up with late festival arrivers. The crowds of civilian onlookers lining the red carpet to catch a peek of a film star have returned, growing to the point where it is almost as difficult to push one’s way into the festival palace building as it is during normal years. Yet the real story is the tale of the return of the festival’s sordid underside.

At least in some quarters, the hedonistic party element has reverted to its normal equilibrium—as has the dizzying dichotomy between the worldly elegance of Cannes and its mirror double of squalor. I had assumed that the party crowd would reassemble in suitably discreet circumstances far away from prying eyes, like private villas and yacht parties. Yet the raucous partying was to be seen everywhere along the beachfront on Saturday evening, though still somewhat scaled back compared to ordinary years. The beach clubs are packed with revelers and the purple Bentleys and Corvettes could be seen cruising down the boulevard with their tops down. Passing by the windows of a night club called Speakeasy situated behind the Carlton hotel, which is closed this year for renovations, one could see revelers bathed in red light dancing on the table to the accompaniment of a jazz band.

At the end of the Rue d’Antibes, a trio of ethereally thin and strikingly beautiful African prostitutes scanned the faces of passing men. Attired in a uniform of skimpy pink shorts and matching tank tops, they marched in military formation, scanning the faces of passing men for interest.

For my part, around midnight, my friends and I found ourselves in an art nouveau style villa with marble floors for the final bacchanal of the evening. A French producer of my acquaintance, a man in his 50s who specializes in distributing Eastern European films took the opportunity to leap into the pool with all of his clothes on.

July 9:

Israeli film got off to a solid start this year at Cannes, with a pair of entries showcased prominently at the festival. Shlomi Elkabetz’s Machbarotr Shchorot (Black Notebooks) created a deeply compelling, document-based story detailing his Moroccan Israeli family’s experience of dislocation, and the tragic early death of his sister, the actress and director Ronit Elkabetz.

The film returns to the terrain that he had previously explored alongside Ronit in a trilogy of films about women and marriage in Israel. Black Notebooks weaves together a melancholy pastiche of family archive, excerpts from To Take a Wife (the film he made with Ronit), and interviews with their tough, Old World Sephardi mother, Viviane, as well as some set piece reenactments of the past. In one, Shlomi is proffered a vision of his sister’s untimely death by a Berber seer—who turns out to be sadly correct.

The film stitches together a poetic journey through time and space. Its content mirrors its form, with Shlomi bouncing back and forth between the family past in Israel and Morocco and the present in Paris, saying farewell to a sister whom he obviously loved very deeply, and to whom he was tightly attached.

The film was featured as a special screening as a sidebar to the main competition. It was sparsely attended, only strengthening my idea that the movie is a true testament to the word “haunted.” I must admit that the melancholy 3 1/2-hour long film was so unbearably sad that I had to walk out after the first two hours.

The second Israeli offering this year is Nadav Lapid’s fourth feature-length film, Ahed’s Knee (Ha’Berech). The knee in question is that of a young woman—an Arab anti-Israeli demonstrator—which a conservative Israeli MK demands be broken to teach her a lesson. An Israeli film director who is casting actresses to play the demonstrator in a film critical of the Israeli government arrives by helicopter in a southern desert town in the valley of Aravah for a screening of his previous film. The screening has been organized by a beautiful young deputy director of the Ministry of Culture Library Department (who is clearly a fan of the filmmaker). The director, for his part, may or may not have PTSD from his time spent fighting on the Syrian border three decades earlier. As a formality, she must make him sign a vulgar and philistine Ministry of Culture form mandated by the new minister of culture—though she clearly knows the form is a travesty violating all of her spiritual and artistic values, which the director also shares. The chemistry between the cynical and rage-filled director and the overeager young librarian is palpable, but instead of attempting to get her into bed, he sadistically attempts to get into her head in order to humiliate the Ministry of Culture.

I have followed Lapid’s career with great interest over the past decade, and believe that he is a very serious talent. Based between Paris and Israel, he is a quirky moralist with an exacting and particular vision and a great eye for composing a frame. He was the first Israeli in history to win a Golden Bear at the Berlinale for his 2019 existentialist drama Synonyms … which is why this film’s unsubtle attack on Israeli government policy and censorship felt so deeply unformed and unsatisfactory. I found out while speaking to prominent Israeli festivalgoers at the afterparties that I was not alone in my opinion, even among those who share the film’s politics, who noted the hypocrisy that a film accusing Israel of censorship had received Israeli state funding. One critic even referred to the film in print as “shrill, strident, and undeservedly included in the Cannes competition” and “nothing short of a bilious broadside of anger at and resentment toward anything to do with the Israeli government.” I would not go quite that far, as the frontal attack style was a concrete aesthetic decision that was always implicit in Lapid’s propensity for heavy-handed moralizing. I do hope, as a longtime appreciator of his work, that his next cinematic effort will be more subtle.

The cancellation of Cannes in May last year was like much else about the film festival—totally uncompromising. Unlike most other film festivals the world over, Cannes refused the switch to an online version. It was surely the correct decision. Certainly on an aesthetic level, the endless, tedious, and all too democratic Zoom sessions would have been totally out of character. Moreover, a large share of the top-tier films which were meant to premiere during last year’s program balked at missing the red carpet treatment (as well as the opportunities for haughty press conferences, photo calls, magazine covers, and myriad opportunities to get drunk on the beach). Accordingly, many of last year’s most avidly awaited films had waited until this year’s festival to have a proper premiere.

As a result, the 2021 Cannes program represents a particularly rich bounty. While it is in many ways shaping up to be an odd and disquieting festival experience, this year nonetheless feels like a historic and exciting time. Wes Anderson’s The French Dispatch, which was set to headline the festival last year, is one film that I am personally quite excited about.

As almost every press account has noted, the Cannes director Thierry Frémaux has dispensed with his baronial custom of giving individual cheek kisses on the red carpet this year. Anthropologically speaking, the kiss represented a symbolic mark of divine grace. Still, despite this noble sacrifice, the social distancing etiquette at Cannes is quite unevenly distributed. Attending the festival will offer anyone a lifetime’s worth of lessons about the tragic division of resources and inequality in life. Filmgoers are certainly not spaced out in the theaters, and many promptly remove their masks during the screenings. The national pavilion parties have been muted so far this year, instead having been replaced with formal dinner events. The festival authorities understand full well how close all of us here stand on the perennial line of “feasting in the time of plague.”

The international film festival circuit can be a serious grind. One will see the same people year in and year out in Cannes, Berlin, Toronto, and Venice. Over the years, festival denizens develop networks of festival friends—people with whom one can exchange film industry gossip, have dinner, and engage in matters of business and narcotics.

Perhaps because of the inescapably depressing subtext of the year, the festival program also has a chicken soup aspect to it, having programmed numerous nostalgic and crowd-pleasing docs about beloved film stars. Jane Par Charlotte, Charlotte Gainsbourg’s film about her mother Jane Birkin, turned out to be one of the hardest films to procure tickets for this year. One can only imagine how chic and inaccessible the afterparty will be.

In addition, a very wholesome and healthy American element was interjected into the opening day of the festival with the premiere of Val, Leo Scott and Ting Poo’s documentary about the life of actor Val Kilmer. The film follows the actor from his Top Gun glory to his unhappy days inhabiting the heavy leather Batman suit (“You cannot hear anyone while you are wearing the mask, and so after a while, people do stop talking to you”), all the way to his late-in-life run as Mark Twain. The out-of-competition doc will be premiering soon on Amazon Prime Video. Val is narrated by the actor’s son, utilizing decades of home video and childhood footage to tell the story of Val’s life in the wake of the actor surviving a serious bout of throat cancer that he candidly admits has ended his career. Throughout it all, he is a merry prankster, a loving family man, a competitive fighter, an intense worker, and a devout Christian.

My European colleagues all thought that the film was monstrously treacly. My French film critic housemate even literally pronounced it be “too American for good taste to bear.” Yet, while I am a deracinated Eastern European, I did come here on a blue passport and was patriotically saddened when French COVID precautions resulted in the scaling down of the 4th of July festivities this year … and so dear readers, I feel no shame in admitting that I greatly enjoyed the film!

The 74th Cannes Festival is finally underway, though it is a shadow of its glamorous former self. Along with the Avignon Theatre Festival, which is being held concurrently, the staging of Cannes signals that the French cultural industry is emerging from an enforced lockdown that was much stricter than anything Americans had to tolerate. The festival was canceled last year during the first panicked days of the pandemic, for only the second time in history—and the first time that did not involve the threat of a Nazi invasion.

Accordingly, until the very last moment, industry insiders were still speculating about whether the festival would take place this year. It had already been moved to early July instead of the usual May dates. But the show and the parties—especially the Marche du Film—must go on!

As the bullet train from Paris bolted south past the stunningly gorgeous French countryside, one could run into countless members of the French film industry and cultural elite on a leisurely stroll through the first-class carriages. I ran into an old friend whom I had not seen in two years because of the pandemic. She is a film industry insider with whom my friends and I had habitually split a house during the festival. She was pregnant with her second child, and I jokingly asked if she had met her new boyfriend at a “sex club.” She smiled sheepishly and admitted that she had met him at the debauched two-month-long party that was Ilya Khrzhanovsky’s DAU installation in Paris. Indeed, it is certainly time to leave hibernation.

Still, even as vaccination rates continue rising in France, COVID-19 infection rates are also rising throughout the country and the Paris region especially—with the new mutations of the virus accounting for ever-greater portions of the infected. The festival instituted strict COVID precautions in response, which have had the effect of making Cannes even more formal, bureaucratic, and hierarchical than it always has been.

Several Americans complained to me that the festival demanded that they provide negative PCR tests every two days. My French vaccination paperwork allowed me to waive the requirement, while the same exact vaccine—Pfizer or Moderna—from America was not considered acceptable. Meanwhile, my Ukrainian roommates were not allowed into the festival palace after their PCR tests were two hours too late. The stern Cannes security guards turned them around for a retest, which they promptly failed, having spent the previous evening drinking heavily. (“That spoils the results sometimes,” the nurse informed them apologetically, politely instructing them to return the following day for a retest.)

The film market—which is in many ways the raison d’être for the festival’s existence—attracted more companies and participants than was expected. Yet the fact that the Marche and the film screenings incorporated different sets of COVID regulations still led to widespread grumbling and resentment toward the draconian guidelines. In some ways, this is an improvement: The usual teeming crowds are almost nonexistent, and one can get a ticket to almost anything. The sunbaked queues that once ensured that people wasted an hour in line for film screenings that they sometimes didn’t even get into (a system which also created artificial scarcity) were replaced with an online registration system that film buffs had spent years clamoring for.

This year, there is no need to throw an elbow to defend one’s spot at the Festival Palace espresso bar. The hordes of cute film students looking for tickets to red carpet premieres are also nowhere to be seen—the tickets are not transferable because of the COVID tracing—nor are the Middle Eastern playboys and European socialites who typically flock to the circuit of side parties scattered in the villas high in the hills above the port.

I am told that one could still book a room at the Martinez even a few days before the festival (Tablet’s intrepid correspondent has yet to compare the quality and quantity of villa, beach parties, and decadent private happenings to that of previous years). A pair of bejeweled Russian women in their mid-50s, ferocious types of the sort that run things, could be heard loudly commiserating in the middle of the street about the fact that their five-star hotels were nearly empty.

But it is still early, and festivalgoers do continue to arrive, so matters may still improve. Nonetheless, it is readily apparent that this year lacks the usual hectic energy, brute grace, magic, and pure aggression of normal years.

Spike Lee, who was victorious at the festival in 2018 with his BlacKkKlansman (likely his most populist effort in decades) returns even more victorious this year as he presides as the president of the jury. The festival banner features the upper half of his face—bespectacled and bemused. It can be seen peeking out at a pair of palm trees almost everywhere around town. Lee wore a bright flamingo pink suit and matching pink sunglasses under a black hat to the red carpet of the opening night ceremony last night. It was a fantastic aesthetic decision, of that there can be no doubt.

Also last night, the suitably grim and surreal Annette, an intense head trip starring Adam Driver and Marion Cotillard and directed by France’s Leos Carax, opened the festival. Driver’s performance was excellent, especially in a film containing such bizarre scenes as a talking marionette baby straight out of ‘60s Czech surrealism and Driver’s character turning into an orangutan and mewling a pop melody while performing oral sex on Cotillard.

The film garnered a six-minute-long standing ovation, though perhaps the audience was cheering the staff for having put the festival together again. Or maybe the ovation was for themselves, for their epic success in having arrived in the South of France despite the myriad obstacles to international travel. They clapped for so long that a bored-looking Adam Driver lit up a cigarette in the middle of the theater.

Vladislav Davidzon is Tablet’s European culture correspondent and a Ukrainian-American writer, translator, and critic. He is the Chief Editor of The Odessa Review and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Atlantic Council. He was born in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, and lives in Paris.