Cartoon Politics

New graphic novels by Harvey Pekar and Guy Delisle illustrate different takes on the Israeli-Palestinian mess

“They could file last month’s story today—or last year’s, for that matter—and who would know the difference?” a frustrated journalist character says in Joe Sacco’s 2009 graphic novel, Footnotes in Gaza (Metropolitan Books). “They’ve wrung every word they can out of the Second Intifada, they’ve photographed every wailing mother, quoted every lying spokesperson, detailed every humiliation—and so what?”

“So what?” is a great question for anyone covering—or following—the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in the Middle East: the rockets traded back and forth, the bombings and arrests, the dispatches about the so-called peace talks, which everyone (except it seems the Obama Administration) realizes were dead and buried somewhere around the time of the Second Intifada. History books are dull, narrative nonfiction didactic, newspapers confusing, TV and film gruesome. But the pictures about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in graphic novels continue to tell a thousand new stories.

Most graphic novels, it should be said, aren’t pro-Israel. The genre itself is subversive, trying to give voice to the underdog, people who aren’t often heard in mainstream media. In 2002, Joe Sacco pioneered the war graphic novel with his stark black-and-white drawings of the First Intifada in Palestine (Fantagraphic Books). Others have followed suit with drawings of the region, like Sarah Glidden’s light and colorful How To Understand Israel in 60 Days or Less (Titan Publishing, 2011), which is less reportage and more about her journey as a liberal, American twentysomething Jew visiting Israel for the first time on a free Birthright trip. For Glidden the underdog sometimes means both sides, but for others working in the genre, including Guy Delisle, Sacco, and Harvey Pekar, “the underdog” is definitively the Palestinians. But objectivity shouldn’t be expected in a graphic novel, even one that purports to be journalism. It’s a personal narrative seen through the author’s eyes.

Now two new graphic novelists have still more to say on the subject, and they have very different visual and reportorial approaches. On one hand, Harvey Pekar, who defined the genre until his death in 2010, penned his last memoir: Not the Israel My Parents Promised Me (Hill and Wang, 2012). Written with J.T. Waldman, the work tries to encapsulate the entirety of Jewish history to understand Pekar’s own changing views on Israel. On the other hand, Québécois graphic novelist Guy Delisle attempts to capture only one year of his life in Israel in Jerusalem: Chronicles From the Holy City (Drawn and Quarterly, 2012). Delisle, a stay-at-home dad who lives in East Jerusalem while his girlfriend works as an administrator for Doctors Without Borders, has no affinity for either side and few preconceptions about the region. Both artists, though, are changed by what they learn.

***

Harvey Pekar’s childhood Zionist indoctrination in 1947 Cleveland was an all-encompassing experience. Still rocked by the emerging horrors of the Holocaust, his immigrant parents, his teachers, and his community celebrated the founding of the State of Israel and all its triumphs with unquestioning joy. Pekar realizes that Zionism doesn’t begin with the founding of the state. “But you gotta look at the big picture, including the old stuff, to wrap your head around what’s going on today,” Pekar, famously bald, dour, and wrinkled, tells J.T. Waldman, a young, curly-haired bespectacled Jew (who also wrote Megillat Esther, a 2006 biblical graphic novel).

Pekar compresses thousands of years of Jewish history into highlights, from the First Exile to the Babylonian Talmud, including Mohammed, the Crusades, and the Golden Age, ending with the U.N. Partition of Palestine. Visually, the historical panels are interesting because they are drawn in the style of their times, with the early history depicted using a mosaic style, the Muslim rule in a traditional Middle Eastern tapestry, the Golden Age without frames to depict its openness. But who wants to learn history from a graphic novel? It’s mere illustration, not commentary. Interspersed with the history sections, Pekar and Waldman wander around discussing Pekar’s beliefs—illustrated in Pekar’s characteristic detailed grayscale—as if the whole world is waiting to find out what Harvey Pekar thinks about Israel.

Well, if you are, here’s the short version: Pekar began to lose faith in the 1960s, after he met other liberals and Marxists outside his sheltered upbringing. Like anyone who has ever grown up, Pekar realizes that not everything is really as it was presented to him. Throughout his late teens and college years, Pekar learns that Israel was sometimes the aggressor in its wars, in its occupation of Palestinian territories, and its dealings with Palestinian people. The subtitle following the already preachy title of Not the Israel My Parents Promised Me, should have been, Israel Does Bad Things Too. Pekar’s memoir has no choice but to be didactic, since he’s never been to Israel. “Yeah, I know I’ve never been to Israel,” he tells Waldman, directly addressing his critics. “But most people haven’t. That doesn’t mean we’re not entitled to an opinion. I read a lot …” He reads a lot? Oh Gawd.

Essentially, Pekar went from believing in one set of indoctrination to another—from his parents’ one-sided Zionistic story to the other extreme of liberal, left-wing America—without ever discovering that the truth lies somewhere in between.

***

Sacco explains (sort of) why graphic novels are so one-sided. In his latest book, Journalism (Henry Holt, 2012), a compilation of comics from war scenes around the world, he calls “Hebron: A Look Inside,” which appeared in Time magazine in March 2001, his “least successful piece of comics journalism.”

“Working for that storied publication seemed to freeze me up, and I dispensed with my more typical first-person approach and reverted to the objective, tit-for-tat reporting I’d learned in journalism school. For this reason, I failed to adequately convey the great unfairness of making the free movement of tens of thousands of Palestinians hostage to the considerations of the few hundred militant Jewish settlers.”

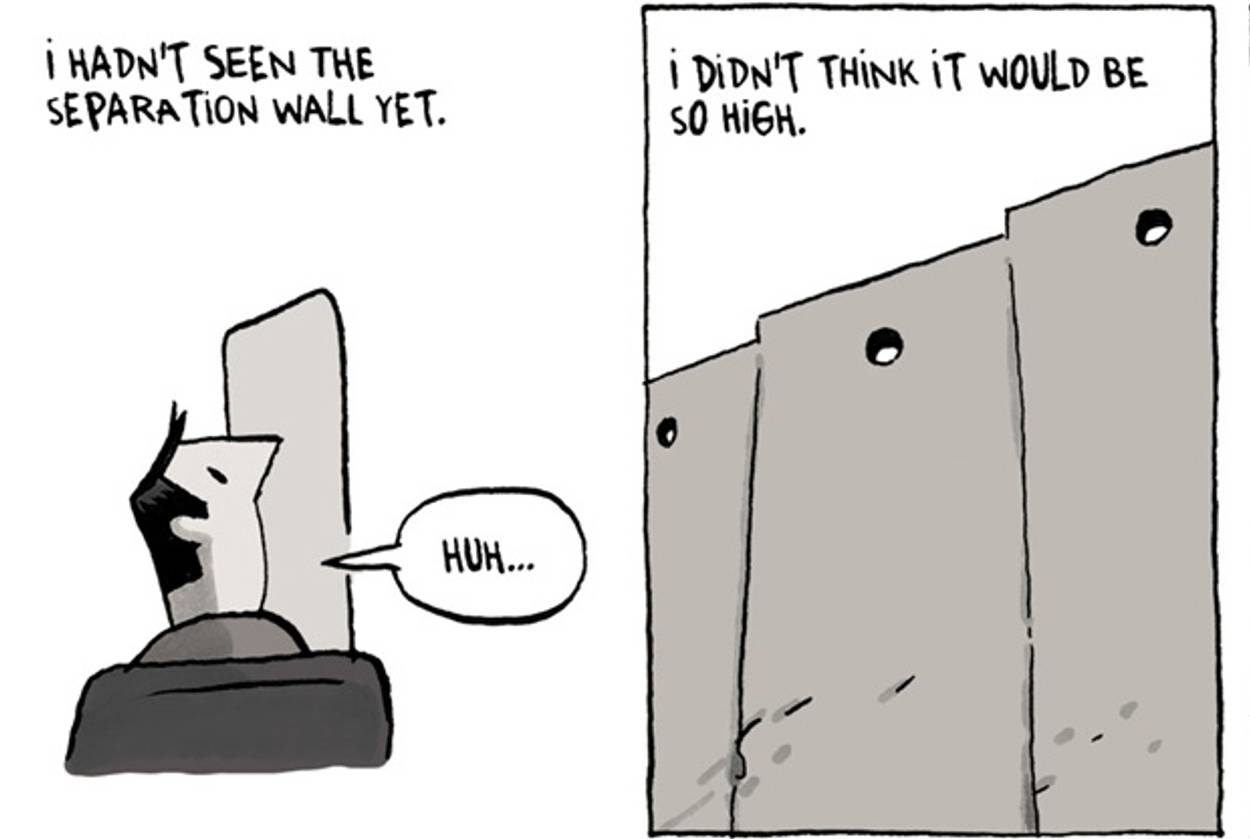

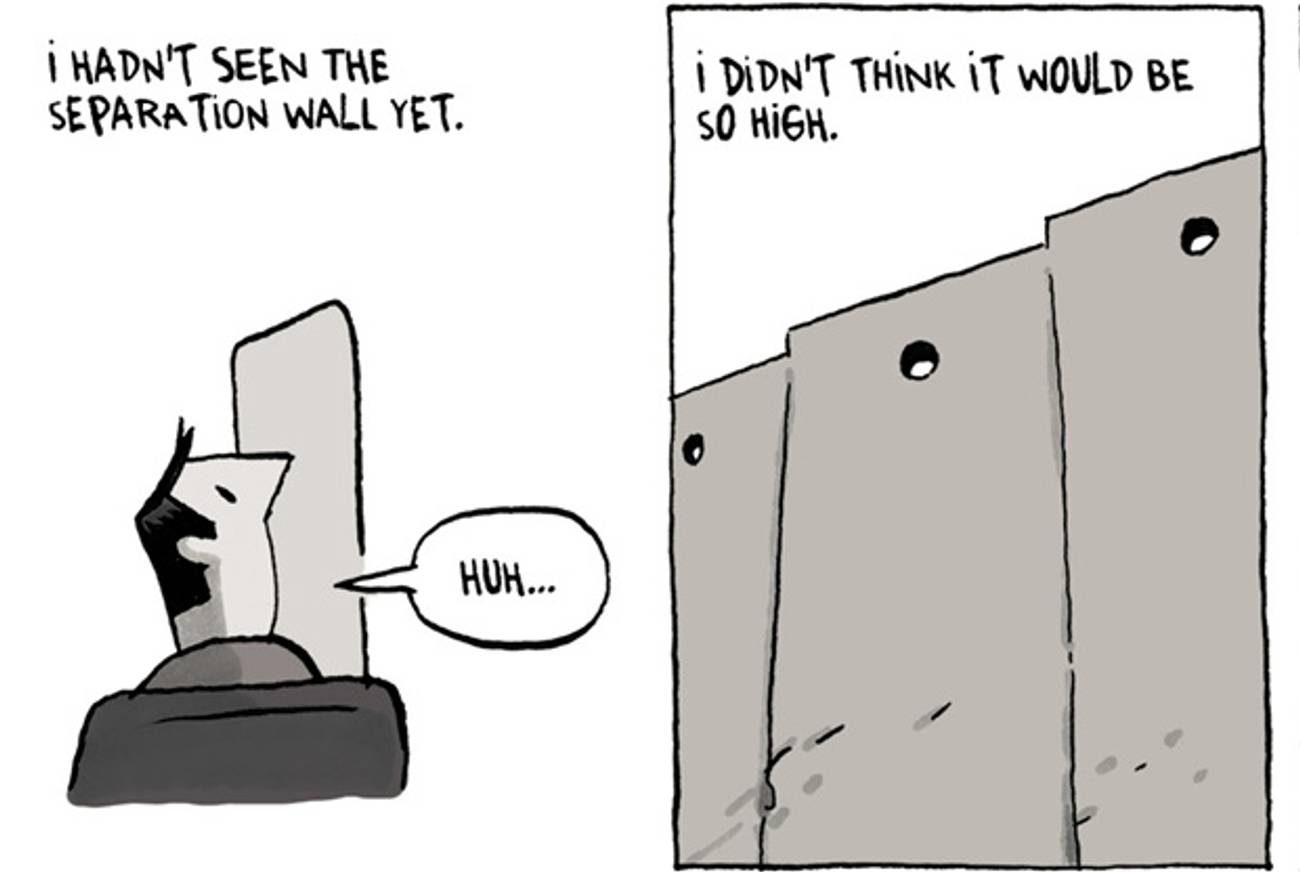

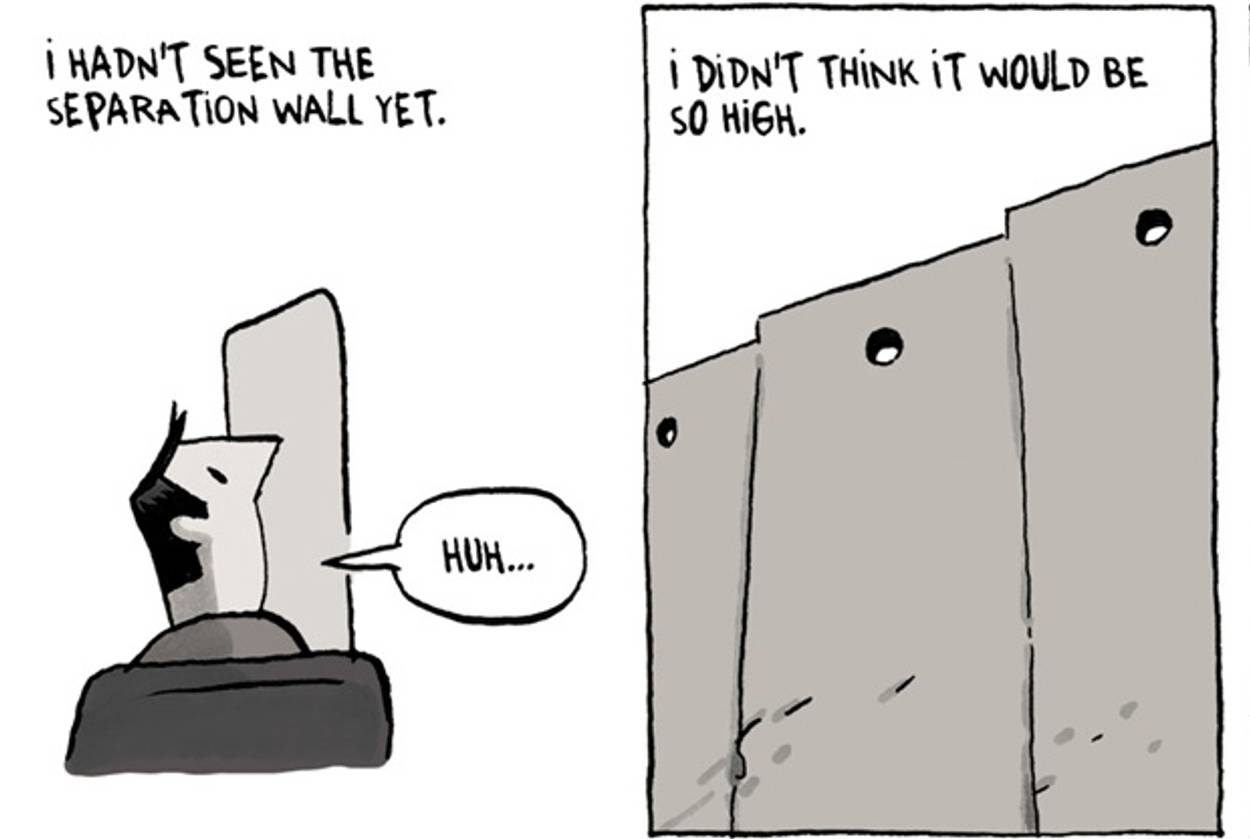

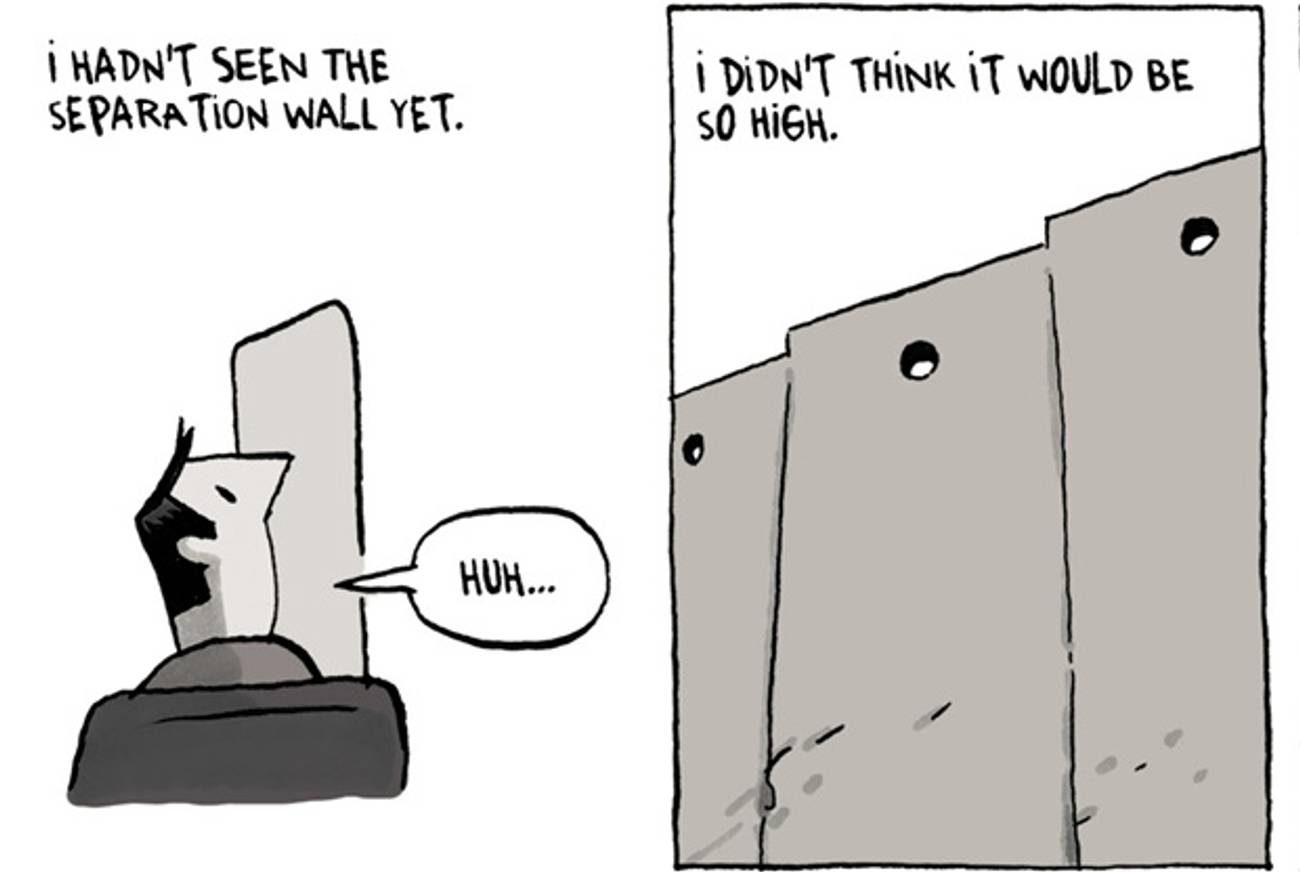

Even if one doesn’t view the conflict as a “great unfairness,” like Sacco does, reading graphic novels can still give people who only see one side of this issue an opportunity to witness and hear the stories of those on the other. A good graphic novel literally illustrates stories from the region—and that’s where Delisle does an excellent job. In Jerusalem: Chronicles From the Holy City, his deceptively simple, one-dimensional drawings—with none of Pekar’s details and shading—depict a more nuanced country.

Delisle’s wife works with Palestinians, and Delisle witnesses daily indignities living in the East Jerusalem neighborhood of Beit Hanina, such as checkpoint harassment, house demolitions, inadequate local services, and (from afar) attacks in Gaza, but at least Delisle is there. On the ground. Living in Israel, if only for a year.

Chronicles lacks Pekar’s comprehensive history of the Jewish people that puts much of the fighting in context, but Delisle captures scenes that give a much more nuanced sense of what life is actually like in Israel: He spends days at the beach in Tel Aviv, marveling at the whole city’s normalness, and he watches how the Israeli press is more critical of Israel than anyone outside of Israel. After he passes a group of people gathering on a corner commemorating the Sbarro bombing in 2001, he learns about the 55 suicide bombings that have occurred in Israel since the Second Intifada in 2002.

This is not to say that Chronicles is objective. Israel hardly comes off well in Jerusalem. But Delisle—who also did the same stranger-in-a-strange-land shtick in his books Shenzhen: A Travelogue From China (2000), Pyongyang: A Journey in North Korea (2003), and Burma Chronicles (2010)—is an artist who clearly just draws what he encounters. He doesn’t have an agenda, like Pekar, who wants to upend everything he learned as a child. Or like Glidden in 60 Days, who says: “I came here, I think I wanted to know for sure that Israel was the bad guy. I wanted to know that I could cut it out of my life for good. But now I don’t know. I don’t know anything. I can see why Israel did some of what they did. You guys are good people. At least, some of you are. Or maybe I’m just being brainwashed just like everyone said I would be.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Amy Klein is a New York-based writer who writes The Fertility Diary column for The New York Times Motherlode blog. Follow her on @AmydKlein

Amy Klein is the author of The Trying Game: Get Through Fertility Treatment and Get Pregnant Without Losing Your Mind and Hadassah’s Ambassador for reConceiving Infertility. Her Twitter feed is @AmydKlein.