A Manual for Living With Defeat

Israeli novelist Orly Castel-Bloom’s latest book, her best yet, is a darkly funny tale of coming to terms with despair

Historically speaking, there have been three ways to write bad Israeli novels. You could do what the writers who were young men and women in 1948 did and write lines like “Alik was born of the sea,” which is about as subtle an approach to myth-making as putting on a Barry White album is to lovemaking. Or, if you were born a generation or two later, and hit your stride in the 1960s and 1970s, you could put on Existentialism like a kid trying on her mother’s coat, discover it was six sizes too large and looked ridiculous, and then return right to the same symbolic space chiseled by your elders; to see this flightless approach in action, read Amos Oz’s My Michael, with its Jewish heroine fantasizing about being raped by the mute Arab twins she had known as a child. Finally, if you were younger still, you could pretend like not having been born in Berlin or London or Paris was merely a geographical oversight that could be corrected with a few meandering novels about young lovers who ponder boredom and ennui and every other feeling except the normal ones you feel when you live in a country that’s attacked by a murderous wave of terror every three years on average. These literary movements have produced scrums of terrible books and overrated writers. But as her latest—and best—book triumphantly shows, they didn’t so much as touch Orly Castel-Bloom.

If you’re at all familiar with Castel-Bloom, it’s likely because of Dolly City, her feverishly funny and pitch-dark novel about motherhood, anxiety, the memory of the Holocaust, and the other emotional tremors of life in modern-day Israel. That book, like Castel-Bloom’s others, was celebrated for giving readers a glimpse into a reality that’s just a shade more surreal than the real thing, writing in sentences that walk the tightrope between the coherent, the clichéd, and the utterly absurd. “I discovered a new type of phobia in Dolly City—Arabophobia, fear of Arabs,” went one of the book’s typical passages. “I once read somewhere that you should tackle fear head-on. Fuck Arabs, if you’re afraid of them. You fuck them—and you see that the devil’s not as black as he’s painted, they’re just like everybody else.” You barely have to be a scholar of Hebrew literature to recognize the dig at My Michael and its overwrought twin Arab violators. For Oz, sex is sublimated through fantasy and used to reflect on the national ethos. For Castel-Bloom, it’s something that normal people do when they want to make themselves feel better.

Which, in Israel, is a sentiment that passes for irreverence, and which has made Castel-Bloom a celebrated, award-winning author. But the same linguistic dexterity that dazzled so much the first time you saw it was, on the eighth or ninth encounter, something you have come to expect, and the author’s world—developed in three collections of short stories, one children’s book, and 11 novels—increasingly appeared less like a vibrant dialogue with reality and more like its own kind of theme park, which is to say a tightly contained space that represents reality through fast and fun rides.

And then came The Egyptian Novel.

Released earlier this year in Hebrew, and, sadly, yet to find a committed American publisher, the book is Castel-Bloom’s bravest. You can tell that right away by looking at its subject matter: Revolving around two generations in a family of Cairo Jews that moved to Israel and struggled to find its slice of the Zionist dream, it is, on the surface, an autobiography of sorts. The family, the Castels, is not another of Castel-Bloom’s polished and brilliant microcosms but her own family, and the central figure in the book is The Oldest Daughter, a nameless author who shares Castel-Bloom’s curriculum vitae and her outlook.

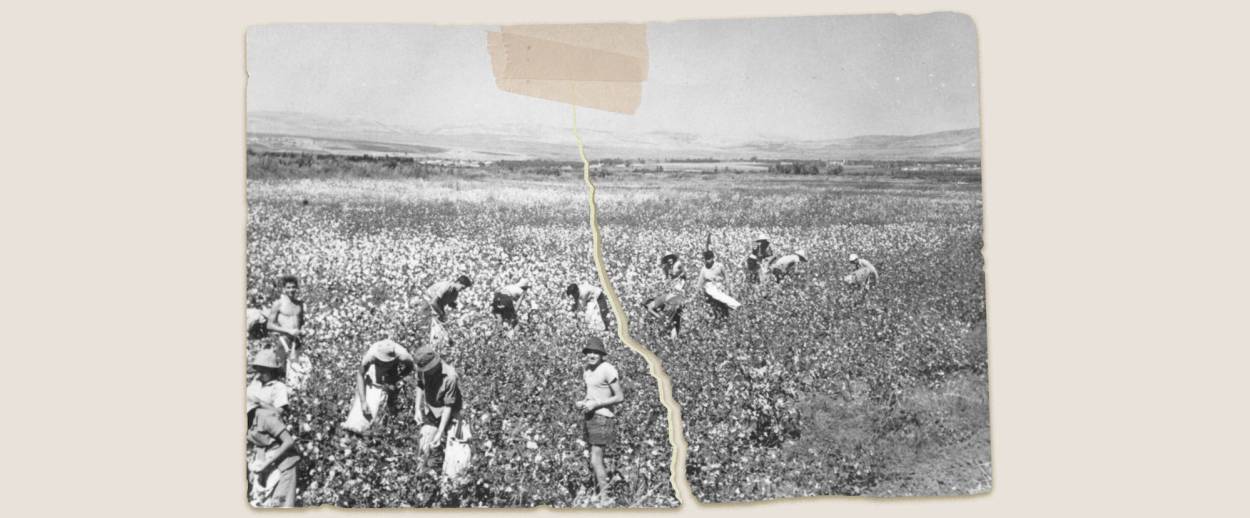

In the hands of a lesser author—and as Castel-Bloom’s talent is peerless, that means nearly everyone else writing in Hebrew today—the above would’ve turned into an exercise in sentimentality, some version of Oz’s elegiac A Tale of Love and Darkness, the sort of work that serious-minded Jewish Hollywood actresses can’t help but turn it into movies. Such an account, however, wouldn’t be fun, and it wouldn’t be true, and it wouldn’t, therefore, be of interest to Castel-Bloom. Instead, to tell the story of herself and her family and the places that they’ve tried to call home and from which they’ve been expelled—Spain, Egypt, the kibbutz—Castel-Bloom layers the heartbreaking and the grotesque and the intolerably mundane and the nearly mythological and the maddening and the transcendantly joyous and all the other emotions that make families work into a novel made up of short stories that sacrifices the factual truth for the much more meaningful ecstatic one.

Take, for example, “The Leveraging Counter Girl,” one of the novel’s most touching stories, a fragment so rich with emotion it could’ve easily been spun into a novel all of its own. The title, of course, is delightfully ridiculous—what’s a counter girl? And what is she leveraging?—and what follows doesn’t fall far behind.

The counter girl is a young woman with black eyes who serves coffee at an all-night convenience store attached to a gas station on a major thoroughfare in northern Tel Aviv. She doesn’t speak much. All she does is make great lattes at three in the morning that greatly please The Oldest Daughter. The consummate literary creature, The Oldest Daughter imagines the counter girl as a sort of milk-stained Anna Karenina and sings her praises to the young men who wander in to the convenience store after a night of partying. The counter girl disappears for a spell, and The Oldest Daughter is convinced that her disappearance is the result of having finally succumbed to one of her suitors and then having been dumped by him. No facts, of course, support this thesis. The Oldest Daughter returns to the gas station frequently; when the counter girl finally returns to work, The Oldest Daughter says something to try and make her smile. “I was very important for human morale,” Castel-Bloom writes, but the counter girl doesn’t smile, and The Oldest Daughter gets consumed by the petty dramas of bickering with her own family in the car en route to a Rosh Hashanah dinner.

Nothing else happens in the story, but the emotional impact it has is immense: Our yearning for a connection with a total stranger, it nimbly argues, stands in inverse correlation with our inability to connect with the ones closest to us. We make up fantastic stories about counter girls so that we don’t have to listen to the trilling complaints of our own mother. That’s what so much of literature—not to mention life itself—is really about.

Not all of the stories in the book are so muted. There’s the bloody tale of Esther, a distant relative and the daughter of a converso family in Spain who escapes the wrath of the Inquisition by raising Iberian pigs, only to discover that her own family’s wrath may be greater. There are The Oldest Daughter’s own parents, tossed from their kibbutz for excessive Stalinism. And there are the relatives who stayed behind in Cairo, “the only household not spoken of in the annals of the people of Israel—those who in the great exodus refused Moses and stayed behind in Egypt as slaves.” None of them are permitted pathos, however, and all have their personal and collective tragedies cut by moments of fierce absurdities or trivialities, like in the story about a close relative’s death not mourned properly because she died right at the end of the month and her family, not wanting to pay another month’s rent, hurried and tossed out all of her belongings and with it her memory.

But for all of its death and disillusionment, the book is rarely gloomy and never hopeless. It is, to quote another wise writer, a manual for living with defeat, a book about life under the weight of a thousand shattered dreams and soured ideologies, about finding grace and sweetness and real satisfaction among the ruins of a fallen Eden, which is what life in Israel in 2015 is and what life as part of a family, any family, has always been and shall forever be.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.