Catalogues and Critical Scholarship: The Fate of Jewish Collections in 19th-Century Germany

Tracing the birth of ‘Jewish studies’ as we know it

Archives tend to put people to sleep. They seem about as exciting as footnotes. Yet the frontiers of knowledge can hardly be advanced without them. What we know of the past is always but “a plank from a shipwreck,” to quote the memorable image of Francis Bacon. Like the Germans, Jews turned to the serious study of their own history in the nineteenth century. For many, especially those trained at German universities, Judaism became a historical phenomenon, subject to the havoc of time and place and ceasing to be static or essential. During the protracted debate in German society in the post-Napoleonic era over whether to extend full citizenship to its Jewish subjects, young Jewish intellectuals began to challenge the dominance of Christian scholars on the nature and history of Judaism with the presumed advantage of the insider. For the first time since the Renaissance, the victims wrote to tell their story in the vernacular rather than in Hebrew. The change in language indicated the shift in targeted audience. Wissenschaft des Judentums was born in battle for admission into the German body politic.

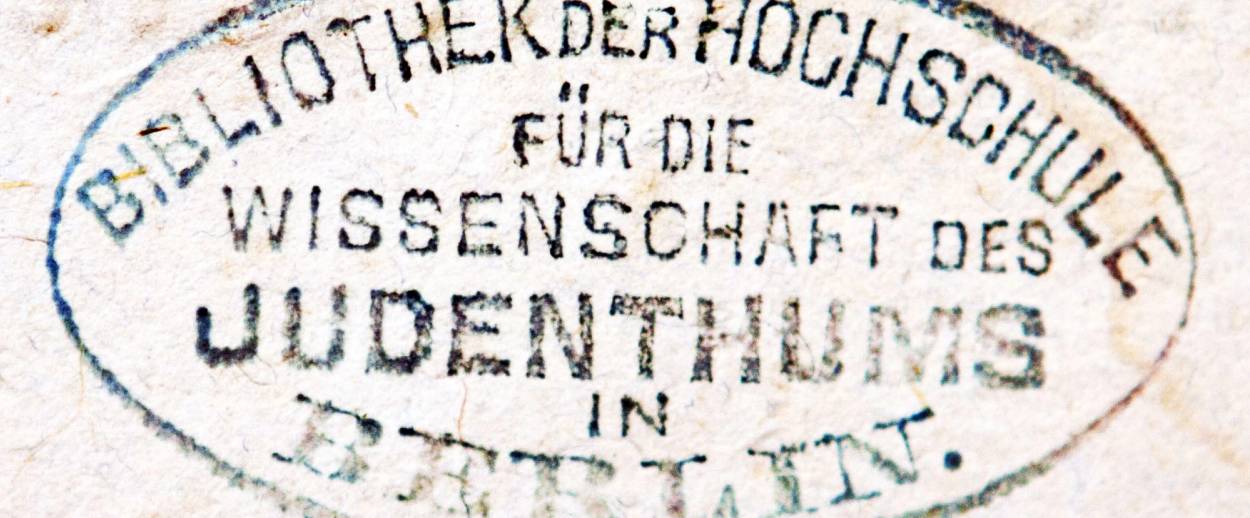

We can pinpoint the year of its birth to 1818 with the appearance of a compact tract of some 30 pages entitled Etwas über die rabbinische Literatur. Its author was a brilliant 24-year-old student at the newly founded University of Berlin incensed by the distorted views of Judaism of Friedrich Rühs, his professor of history, who had denounced in writing the recent partial emancipation of Prussian Jews. In protest, Leopold Zunz dropped his class and set about to write a rebuttal dripping with sarcasm. To his credit, he soon abandoned the project to elevate the discourse with a sweeping conceptualization of what a genuinely historical study of Judaism would entail. In an age when scholarship was embracing the critical study of every aspect of human culture, why, he asked, was Judaism still being dismissed by the unexamined, recycled claims of religious prejudice? Medieval Jews had produced works on astronomy, medicine, mathematics, geography, architecture, business, industry, music and art. The term “rabbinic literature” completely obscured these secular interests and precluded understanding Judaism as a well-rounded cultural phenomenon. Zunz proposed instead the adjective “neo-Hebraic” (as opposed to biblical Hebrew) or simply “Jewish” to properly encompass the dynamic diversity of the literary corpus.

Under the three broad rubrics of ideas, language and history, Zunz laid out not only the genres of the field, but using the few flawed extant catalogues available also cited published and unpublished samples of many. In a sense, Zunz’s tract served as a bibliography which vindicated his conceptual revolution. Prejudice fed by ignorance fueled the raging debate over Jewish citizenship in Prussia. A deep and dispassionate study of Judaism required above all recourse to the archives. By way of example, Zunz promised to publish soon a Latin translation (still the lingua franca of German academic life) of a Hebrew ethical treatise by a thirteenth-century Sephardic philosopher. Because he had only a single manuscript of the Hebrew text, he was as yet reluctant to publish the original. The initiative had a twofold purpose: to show that medieval Jews were not benighted, though modern savants were for speaking ex cathedra about a subject whose contours they could scarcely imagine.

By virtue of its vision and rigor, its erudition and passion, Etwas was destined to become the cornerstone of modern Jewry’s turn to history, the intellectual equivalent of its political emancipation. In the universities to which German Jews, especially in Prussia, streamed out of all proportion to their numbers in the general population, they were exposed to a lethal combination of the canons of historical thinking and the evolutionary thrust of German philosophy, which relegated Judaism to a past long transcended.

***

The first to give voice to an insider’s view of the Jewish experience was Zunz’s school mate and friend Isaak Markus Jost. Sadly, however, his nine-volume Geschichte der Israeliten composed in haste from 1820 to 1828 and covering approximately 2,000 years of Jewish history from the Maccabees to 1815 failed to break much new ground. Jost contented himself with a narrative history largely restricted to the external history of the Jews (except for his jaundiced treatment of rabbinic Judaism) by reordering what was already known. In his rush to mollify public opinion, he skipped all archival research to erect an edifice that stood without any semblance of a foundation.

In contrast, Zunz worked vertically rather than horizontally, and his 1832 one-volume history of Judaism’s sermonic literature became the inspiration and gold standard of the entire Wissenschaft enterprise. By focusing on internal history, Zunz brought out what Jews did for themselves and not what others had done to them. In place of sovereignty and a sacred geographic center, he argued, they fashioned a mobile sanctuary for prayer and study. The synagogue emerged to sustain their spiritual resilience throughout their long exile, embodying the forum in which they could also give expression to their national aspirations. Equally striking, Zunz now identified, dated and described the homiletical (that is, midrashic) writings to which the synagogue gave rise. Painstaking textual analysis transformed a chaotic literary legacy into a coherent body of religious creativity. In the process, Zunz highlighted countless formerly peripheral, unknown and even no longer extant texts which established beyond dispute that the sermon was not a modern invention of synagogue reform.

However, to write history from the bottom up by enlarging the number of documents at our disposal demands, above all, the availability of relevant collections, and these were hard to come by in the Germany of the 1820s and would get even harder. Prior to publishing his watershed work, Zunz had occasion to consult the largest Hebrew library in Germany in August, 1828, when he spent five days in Hamburg scouring that of David Oppenheimer. A printed catalogue of its 4,500 printed books and 780 manuscripts had appeared two years earlier, making the treasure trove momentarily accessible. The library harbored the singular legacy of the former rabbi of Prague and Bohemia, who had it transferred to Hanover for safekeeping several decades before his death in 1736. Johann Christian Wolf, a professor of Oriental languages in Hamburg, brought it to the attention of the scholarly world by utilizing its wealth in his celebrated four-volume catalogue Bibliotheca Hebraea (1715-33), which bequeathed to Zunz’s generation a far-flung study of Hebrew bibliography. Because of Wolf’s involvement, Zunz quipped cynically in his pioneering 1845 survey of extant Jewish libraries and catalogues, nearly all of which were private, that Oppenheimer’s library was “one of those few monuments erected by Jews and preserved by Christians.”

Simultaneous with the publication of his book in 1832, Zunz became reacquainted with Heimann Joseph Michael, who also lived in Hamburg, and with whom he had played as a child. Like Oppenheimer, Michael was a learned bibliophile, though a businessman rather than a rabbi. The two men bonded immediately and an extensive correspondence ensued that attests the degree to which Zunz drew on his collection and erudition for his research. Circumstances permitting, he would have readily moved to Hamburg. At his premature death in 1846, Michael had amassed a collection of 5401 books, nearly all Hebraica, and 860 manuscripts. Zunz wrote the forward to the subsequent catalogue, in which he said of his friend: “There are people about whom no one has heard while the spirit still animates them. Only at death does the world learn what they have accomplished in seclusion.”

To the dismay of Zunz and his few learned compatriots, both collections ended up in England. In 1829 the Bodleian Library of Oxford University purchased Oppenheimer’s legacy for the modest sum of 9000 thalers, while in 1848 the British Museum acquired Michael’s books and the Bodleian, his manuscripts. Zunz intervened in both instances with Prussian authorities in a vain effort not to lose access to these treasures. On August 20, 1846 Prussia’s Minister of Education and Church Affairs, J.A.F. Eichhorn, responded quickly, curtly and coldly to his long letter of August 17 that “I cannot take up the purchase of the library.”

That same summer of 1846, Zunz’s friend Meier Isler of Hamburg, who worked in the city’s library, issued an appeal to the wealthy Jews of his city on the front page of Der Orient, the clearing house for Jewish scholarship in Germany, to add Michael’s extraordinary collection to that of the local library, which, he claimed, already owned the largest of any public library in German:

It is now nearly 20 years that a similar treasure, assembled for the same purpose, was shipped out of Germany to a remote corner ofthe scholarly world, where buried and inaccessible it is of no value to scholarship. … Let us not commit such a travesty a second time. May the new interest in Jewish scholarship that since then has been aroused contribute to fostering an appreciation for this vital task. It is a matter of honor for Germany, and especially for its Jews, that this collection remain here.

***

The appeal, unfortunately, fell on deaf ears. The opportunity afforded by both transactions could not overcome the pervasive lay indifference which constantly hampered the institutionalization of the new science in Germany. Communal apathy and university hostility destined many scholars of Judaica to live at a subsistence level, far removed from the wellsprings of their research. Thus while German universities surely imbued young Jewish scholars with the tools and perspectives of critical scholarship, the truly great collections of Hebrew rare books and manuscripts were to be found in Oxford, London, Paris, Leiden, Parma and Rome, which they could ill afford to visit.

Yet without a modern catalogue, their treasures were unknown and inaccessible. Bibliography was the indispensable handmaid of critical scholarship. Toward that end, the Bodleian invited Moritz Steinschneider, Zunz’s protégé, in 1848 to catalogue its collection of printed books. The project would make him the greatest Jewish bibliographer of his age, if not of all time. In truth, he wanted to catalogue its incomparable horde of manuscripts, for they teemed with far more novelty. Both he and Bulkeley Bandinel, the librarian, regarded the book catalogue as a stepping stone to the manuscripts, and his five trips to Oxford over the next decade yielded many a dramatic discovery. Altogether he toiled intensively for 13 years with the complete confidence and personal assistance of Bandinel to produce an encyclopedic Latin catalogue that covered every book in the collection printed before 1732. Along the way with Bandinel’s encouragement and checkbook, Steinschneider purchased rare books in good condition to fill in lacunae. The four stout volumes of the catalogue, amounting to more than 9500 entries packed with dense biographical data, cost the Bodleian a grand total of 2,050 pounds. Though Steinschneider’s health did not permit him to continue with the catalogue of its manuscripts, the exhaustiveness and precision of his book catalogue would never be duplicated.

Despite the imperialism of the British libraries, their German counterparts were still heirs to important collections of Hebrew manuscripts. With every manuscript a potential game changer, the quality of a collection mattered as much as its size. By the 1870s in a quick succession of German catalogues of Hebrew manuscripts in the libraries of Munich, Hamburg and Berlin, where he now worked on a very part-time basis, Steinschneider, unearthed the treasures that awaited the diligent scholar. Manuscripts often do not self-identify. What made Steinschneider a uniquely reliable guide is that he read his manuscripts rather than scanned them before describing their content and identifying, where possible, their author and provenance. With astonishing alacrity, he deciphered different scripts and alphabets to master a wide range of literary genres. In consequence, his catalogues abounded with precious information. He listed the title and author, where known, of each manuscript, analyzed its subject matter, often quoting interesting passages, format permitting, and finally cited the modern scholars who had written on it, while correcting their errors. His commitment to truth strained many a friendship.

By his count Munich had 418 codices, that is bound volumes often containing more than one manuscript, Hamburg 355 and Berlin 259. Besides having the largest and oldest collection in Germany, Munich also had the most varied. Indeed, Steinschneider averred that in terms of diversity, Munich was the equal of the much larger manuscript collections of Oxford, Paris, London and the Vatican. Years before, Max Lilienthal, a young rabbi with a doctorate in search of a career, had composed an incomplete and badly marred catalogue of Munich’s Hebrew manuscript collection, which he published in the literary supplement of the Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums from May 19, 1838 to November 16, 1839. The disjointed format of the catalogue was never consolidated by republication in book form, though Steinschneider’s personal collection of his own publications does contain an interleafed Handexemplar that swarms with his handwritten corrections and additions. It is evident that it served as the point of departure and road map for his own catalogue.

Notwithstanding its flawed condition and inaccessibility, Lilienthal’s catalogue did catch the eye of M.H. Landauer, who hastened to Munich on a subvention from the government of Wüttemberg to pore over its substantial corpus of Kabbalistic manuscripts. Sickly from birth and in deteriorating health, Landauer had studied at the universities of Munich and Tübingen before passing his state exam in Württemberg to become a rabbi. He would die in 1840 at age 33. In the short time allotted him in the library archives, he read voraciously and empathetically. The dozens of notebooks he left behind pulsated with an inchoate but coherent history of Jewish mysticism. When edited and published posthumously by Julius Fürst, the editor of Der Orient, in 1845, his profusion of insights and conjectures not only put the study of Kabbalah on the Wissenschaft agenda, but attracted other scholars to head for Munich.

The ultimate significance of a collection, however, eludes the confines of a catalogue and is better captured by highlighting the research it spawned and fertilized. To illustrate this criterion, I should like to close by mentioning three Jewish scholars of world renown whose research is indebted to their contact with Munich. My first example is Gershom Scholem, the great master of Jewish mysticism. As an adolescent in Berlin prior to World War One, he had embraced Zionism and immersed himself in a serious study of Hebrew sacred texts. By 1919, he had discarded his plans to pursue a doctorate in mathematics at Göttingen and decided instead to go to Munich because of its wealth of Kabbalah manuscripts to advance his passion for Jewish mysticism. His dissertation on an early, fragmentary and difficult kabbalistic text, known as Bahir (light) and first published in 1651, broke new ground in part because Scholem was able to base his translation and commentary on a less garbled manuscript in Munich from 1298. Years later he would learn that it was with this same manuscript that the Renaissance virtuosa Pico della Mirandola had begun his own study of Kabbalah in 1486.

In 1923 Scholem left Germany for Palestine to eventually turn the new and tiny Hebrew University into the world center for the study of Jewish mysticism. It is striking that his pioneering work after the dissertation should begin with a catalogue in 1927, not exactly an inventory of primary sources, to be sure, published or unpublished, whose state of disorder defied the capacity of any single scholar, but rather a catalogue raisonné that covered some 1219 secondary works written in the last 400 years on the subject of Jewish mysticism. Scholem’s dissertation and catalogue appeared as volumes one and two of a grandious research project on the literature of and scholarship on Jewish mysticism by a society that proudly bore the name of Johann Albert Widmanstad, the sixteenth-century Renaissance scholar whose gift of manuscripts had firmly laid the foundation of Munich’s collection of Hebraica.

Among Munich’s prize possessions was the only surviving manuscript of the Babylonian Talmud, the fountainhead of rabbinic Judaism. Dating from 1342, it was not only complete but uncensored by papal authorities. Traditional scholars had long known that over the centuries scribal errors had increasingly corrupted many a Talmudic passage now petrified in the printed text. Since the early 1860s, Fürchtegott Lebrecht in Berlin, an admirer of Zunz and a student of Wilhelm Gesenius, Halle’s great grammarian and lexicographer of biblical Hebrew, had been pushing the cause of a critical edition of the Talmud. But it was to be Raphael Nathan Rabbinowicz, a 30-year-old Lithuanian yeshiva product untouched by the philological training of a German university, who seized the initiative to come to Munich to utilize its unique Talmudic manuscript as the focal point of a critical edition.

Arriving penniless, he quickly garnered for his daunting vision the enduring and unstinting support of Abraham Merzbacher, an ordained Orthodox rabbi, banker and avid collector of Hebraica. From 1868 to 1888, the year of his untimely death, Rabbinowicz produced 14 volumes in Hebrew covering more than half of the Talmud. In parallel columns, each page showed those passages of a tractate in which a divergence occurred between the printed text and the Munich manuscript. At the bottom of the page, Rabbinowicz cited and explained still other readings of each passage from other manuscripts and Talmudic commentators that he had assembled in order to enlarge the pool of textual variants. Heinrich Ehrentreu, a Hungarian Orthodox colleague in Munich, who would later tutor Scholem in Talmud when he came to the city, completed, edited and published in 1897 yet a fifteenth volume left unfinished by Rabbinowicz at his death. Dikdukei Sofrim (scribal variants), as he called his testament to originality, erudition, hard work and perseverance, revealed for the first time the extensive fluidity of the Talmudic text. Still, he insisted in his introduction that his exercise in lower criticism was to have no bearing on accepted halakhic opinions that derived from the standard text. What motivated him was piety, not impiety: to cleanse the dominant sacred text of traditional Judaism of error and corruption. With the continued discovery of ever more Talmudic fragments and the awesome technology of the computer, the quest for a critical edition of the Bablylonian Talmud in our own day is finally nearing a semblance of completion.

Unlike Scholem and Rabbinowicz, Steinschneider came to Munich in mid-career, highly respected and intensely focused. Cataloguing its Hebrew manuscripts did not actually require his residing in the city. The library obliged him by sending the codices to Berlin, which he finished perusing by 1869. That he saw fit to do two editions of his Munich catalogue in 1875 and 1895 is eloquent testimony to his regard for the importance of the collection. It was the only one of his catalogues to come out twice. The second edition was some 50 pages longer and carried more excerpts than the first. Its bibliographical data also evidenced the extent to which contemporary scholarship had utilized the collection in the intervening 20 years. In his massive lifetime’s work Die hebräischen Uebersetzungen des Mittelalters und die Juden as Dolmetscher of 1893, which was almost entirely based on manuscripts, he cited Munich manuscripts some 500 times.

It was the exceptional diversity of the collection that invigorated Steinschneider’s research agenda. To his delight, he found there an abundance of manuscripts in Hebrew and Judeo-Arabic (Arabic in Hebrew letters) in the fields of medicine, mathematics and philosophy. Many were in fact rare or unique copies of Arabic philosophic texts that shed new light on the legacy of such Islamic giants as Al-Farabi, Al-Gazzali and especially Averroës, the primary Muslim expositor of Aristotle. Indeed, Steinschneider was fond of reiterating that Averroës’s corpus survived the Middle Ages largely in the guise of Hebrew translations. His discovery in Munich of a thirteenth-century Hebrew summary of Plato’s philosophy led him to author a major work on Al-Farabi in 1869 and thereafter to publish a spate of mathematical and medieval studies deriving from its manuscripts.

In short, Munich provided Steinschneider with invaluable ammunition to expand his lifelong campaign to alter the cultural profile of medieval Jewry. In libraries across Europe, its literature was still being classified under the category of Bible and theology, as if writing among medieval Jews were restricted to their rabbis. And yet in the Islamic world, Jews wrote in Arabic, produced a significant body of non-religious literature and played a vital role as translators in the circuitous chain of transmission that brought the wisdom of the Greeks to the Christian West. By going underground, that is into the archives, Steinschneider could show that above ground, the spirit knew no ghetto. In 1843 scarcely a single Arabic original of a Jewish text had as yet seen the light of day. By century’s end, many a classic preserved only in Hebrew translation had been reconnected with its underlying Arabic medium in which it was originally written. Moreover, a host of new unknown texts authored by Jews or Jewish converts to Islam in disciplines impinging on Judaism but well beyond it, added dramatic evidence that Jews were an integral part of the fabric of Islamic civilization in the era of its ascendancy.

Spearheaded by Steinschneider in Berlin and Salomon Munk and Joseph Derenbourg in Paris during the second half of the nineteenth century, this extraordinary work of excavation not only paved the way for the appreciation of the flood-tide of documents that started flowing from the Cairo Geniza at the turn of the century, but also matched it in scope and significance. Above all, this cadre of polymaths established beyond cavil the inextricable link between archives and history, their catalogues and critical scholarship.

***

The essay was originally published in German in Muenchner Beitraege zur Juedischen Geschichte und Kultur, 2011, pp. 9-23. The English version is printed with permission.

Ismar Schorsch, Rabbi Herman Abramovitz Professor of Jewish History and Chancellor Emeritus at the Jewish Theological Seminary, is the author of, among other books, Canon Without Closure. He is at work on a biography of Leopold Zunz.