Marc Chagall and the People’s Art School in Vitebsk Reunion

Old conflicts in the air and on display at the Jewish Museum

There’s a reunion in progress on the second floor of the Jewish Museum in New York. The current exhibit, Chagall, Lissitzky, Malevich: The Russian Avant-Garde in Vitebsk, 1918-1922, brings together three artists who were leading creative forces at the art school founded after the Russian Revolution by Marc Chagall in his native city, Vitebsk. Old conflicts are in the air and on display.

The Jewish Museum, like the People’s Art School, is housed in a repurposed mansion, with the difference that in New York the Warburg family voluntarily bequeathed their mansion to the museum whereas the Bolsheviks forcibly appropriated the Vishniac mansion for Chagall’s use. The Jewish Museum’s small, irregularly shaped rooms, its wood paneling and grand fireplace, duplicate the close quarters of the original school and its perilous intimacy. For the visitor to this reunion, as for the original students and teachers at the school, there can be no avoiding the stark shifts and differences in artistic style nor the uneasy feeling that, behind them, lurk differences equally stark and probably troubling.

How could Marc Chagall’s colorful, emotionally expressive paintings coexist with Kazimir Malevich’s suprematism, an artistic movement whose most famous painting is a painting of a black square? The gallery text informs the visitor that El Lissitzky’s illustrations for the Passover song “Had Gadya” showed “a turning point in Lissitzky’s work, demonstrating his shift from champion of Jewish cultural tradition to avant-garde artist.” This is not a benign shift. The Bolsheviks are at the door and a 20th-century nightmare looms.

The troubling trend was not limited to Lissitzky. Other Jewish artists at the People’s Art School did the same. The gallery text again: “Abandoned by his disciples, who preferred to learn from Malevich, Chagall left the school in June 1920.”

A film clip of Lenin outside the first gallery sets the stage for the drama about Russia’s revolutionary politics and Vitebsk’s art. Vitebsk, “far from the cultural centers of Moscow and Petrograd,” had become the “laboratory of the new world.” In this new world, being leftist, not Jewish, was the formula for success. Chagall and his “individualistic art” lost out to Malevich who “embraced the idea of work made collectively.”

Yet the politics of right and left do not fully describe Vitebsk’s political alignments. Vitebsk was the center of Jewish life in the Pale of Settlement. Life there, like life among the Russian Empire’s other ethnic, national, religious and linguistic groups, was also being shaped by the struggle for civic rights and self-definition. In this drama, Vitebsk was not an incongruous choice for a Bolshevik art school. It was already a “hot spot” for cultural debate long before Chagall established the People’s Art School.

Not only Chagall, Lissitzky, and Malevich star in this drama. Yehuda Pen, Chaim Zhitlovsky, and S. An-Sky also have roles to play. All three shaped Vitebsk’s cultural debate. All three had ties to Vitebsk. In this drama, Chagall is not the solitary champion of Jewish tradition, Lissitzky is not his disciple and Malevich is not an outsider. Each of the three artists had unexpected affinities.

All three artists were provincials. Each artist had to find his way out. Each had to figure out what to bring along. Each left behind hurt feelings. Although the three artists ended up in different places, both stylistically and geographically, their routes were similar. Both Chagall and Lissitzky studied at Pen’s art school, which opened in 1897, the first in the Pale of Settlement and where Yiddish was the language of instruction and no classes met on the Sabbath. Both participated in the ethnographic expedition, organized by An-Sky, to record and collect remarkable examples of Jewish folk art in the Pale. Neither attended any of Chaim Zhitlovsky’s packed lectures in New York City, yet they would have understood his cosmopolitan aspirations. Both got as far away from Vitebsk as soon as they could. Lissitzky was 19 when he arrived in Darmstadt to study. At 23, Chagall moved to Paris.

Chagall’s early work, before he went to Paris, shows the distinct influence of Pen and An-Sky in his choice of subject matter. Pen encouraged his students to paint scenes from everyday Vitebsk life. Efros praised him for his eclecticism, for the way that he combined Jewish “tradition” and modernism.

Chagall’s paintings in Paris left much of that behind. These are the paintings that have proved to be the key to unlocking the door through which Jewish Vitebsk entered the wider world: A Chagall mural decorates the dome of the Paris Opera.

The modernism that Chagall learned in Paris spoke a language of the self, stripped of its messy particulars. Chagall’s Vitebsk was the setting of Chagall’s personal symbolic world, turning the everyday scenes of his unremarkable hometown into a magical dreamscape. Chagall’s crowd of recurring characters (the Wandering Jew, the floating lovers) liberated their souls from the mud of their origins, free to act out their own brand of universal and eternal themes.

In Chagall’s paintings, the documentary specificity of Pen’s paintings, and of his own early paintings, is absent. Viewers could learn little from them about the actual Vitebsk. They could be misled into thinking that it was a shtetl and not a small city (population 100,000) full of artisans and light industry. Chagall’s paintings neither preserve the details of which Yiddish newspapers Jewish artisans read, as Pen did, nor do they make use of the folk art elements, as his own and Lissitzky’s earlier work do. And yet, hundreds of thousands of Jews cannot be wrong. Chagall captured something that has come to be identified with the Jewish spirit.

***

Chagall himself has come to represent Jews and to command an automatic sympathy, as this exhibit demonstrates. In claiming that “Malevich’s followers … unjustly forced … Chagall, to leave Vitebsk” and in calling the students at the People’s Art School his “disciples” who “abandoned” Chagall for Malevich, the museum text adopts Chagall’s language and point of view, but only part of it. Chagall did say, about Lissitzky, “My most zealous disciple swore friendship and devotion to me. To hear him, I was his Messiah. But the moment he went over to my opponent’s camp, he heaped insults and ridicule on me.” He did call Malevich “a dishonorable intriguer who did not know the kind of art Vitebsk needed.” But these quotations, which come to us via Abram Efros, Chagall’s contemporary and ardent promoter, omit Efros’ concluding comment. “Incidentally, he [Chagall] got over it [his anger against Malevich] quickly.”

Efros knew all about Chagall’s tantrums. Not only Malevich and Lissitzky provoked them. In looking back on the installation of Chagall’s legendary murals at the Moscow State Jewish Theatre, Efros recalled how Chagall objected to props, to stagehands touching his sets, and to actors going on stage:

He cried real, hot, childish tears when rows of chairs were placed in the hall with his frescoes. He exclaimed, “These heathen Jews will obstruct my art, they will rub their thick backs and greasy hair on it.” To no avail did Granovsky and I, as friends, curse him as an idiot; he continued wailing and whining.

Efros did not think Chagall was an idiot, and nobody thinks Chagall actually believed his co-religionists were “heathen.” On display at the Jewish museum are early drawings for those very frescoes threatened by Jewish hair grease. The wall text explains that these are examples of the way in which Chagall made “mischievous and ironic use of its [suprematism’s] formal vocabulary.” There’s no knowing Chagall’s motives, but the embrace of this avant-garde formal vocabulary is everywhere in the Moscow State Jewish Theatre murals; it contributes to their startling dynamism.

These frescoes, painted shortly after he left Vitebsk, show that Chagall, like his so-called disciples, was influenced, even stimulated, by Malevich. And why not? Chagall was also influenced by the artistic styles he saw in Paris. Like Lissitzky and his Vitebsk students, he experimented with different styles.

Chagall never articulated the reasons why he no longer integrated folk art motifs into his painting, but Lissitkzy did. In his 1923 essay, “Memoirs of the Mohilev Synagogue,” Lissitzky explained his disenchantment with a story about finding a pattern book in the library of the Mohilev synagogue and realizing that this supposedly Jewish folk art had been copied from a pattern book and was identical to the decorations in a Christian church. Jewish folk art was not uniquely Jewish. If he wanted to express a Jewish spirit, his own spirit, then adhering to those “traditional” models, that is, being a “champion of the Jewish tradition” was no more Jewish than his interchanges between painting and architecture or PROUN, as Lissitzky dubbed his Vitebsk, avant-garde, works.

Other Jewish artists from Vitebsk shared Chagall and Lissitzky’s outlook. Maria Gorokhova, the wife of the artist Lev Yudin, recalled:

Every student has his own vision of the world, his own experiences and perceptions. This must not be destroyed, but the culture of past and current art should be laid down to create a foundation for it.

Can a Jewish artist have “his own vision of the world”? Chagall and Lissitzky both answered yes. Malevich agreed. Maria Gorokhova described Malevich’s method this way: “Working with a student in different systems, Malevich strove to reveal his potential creative abilities, to give him the culture and freedom to feel and see the world through his own eyes.”

Malevich’s success in Vitebsk had to do as much with being a provincial as being a leftist. A Polish-Ukrainian Catholic, Malevich grew up in Ukraine and wound up in Kursk, a medium-sized city like Vitebsk. Malevich, like Chagall, was also not fluent or quite literate in any language. Malevich had spoken Polish at home, Ukrainian outside of it and, upon moving to Moscow, he never mastered Russian.

A provincial outsider, he was mistaken for a Jew. In letters dated May 1916, a certain Ivan Aleksandrovich Aksenov wrote about Malevich to a friend. “Send me his idiotic booklet Suprematism. … He can scribble something or other about the exhibitions (without fee, for now), we’ll correct his grammar and it will be excellent.” In another letter the same month, Aksenov speculated about the background of this semiliterate, idiotic and desperate hack: “What stripe is he? Isn’t he a Jew? Let me know, please.”

Malevich took a path out of the provinces that resembled Chagall and Lissitzky’s. Like them, he also flirted with folk art. For a while, he imitated the style of peasant woodblocks, called lubok. Before he showed his famous “Black Square,” as a painting, it was a needlepoint design on a pillow at an exhibit of kustar crafts, the Russian arts and crafts modeled on folk designs.

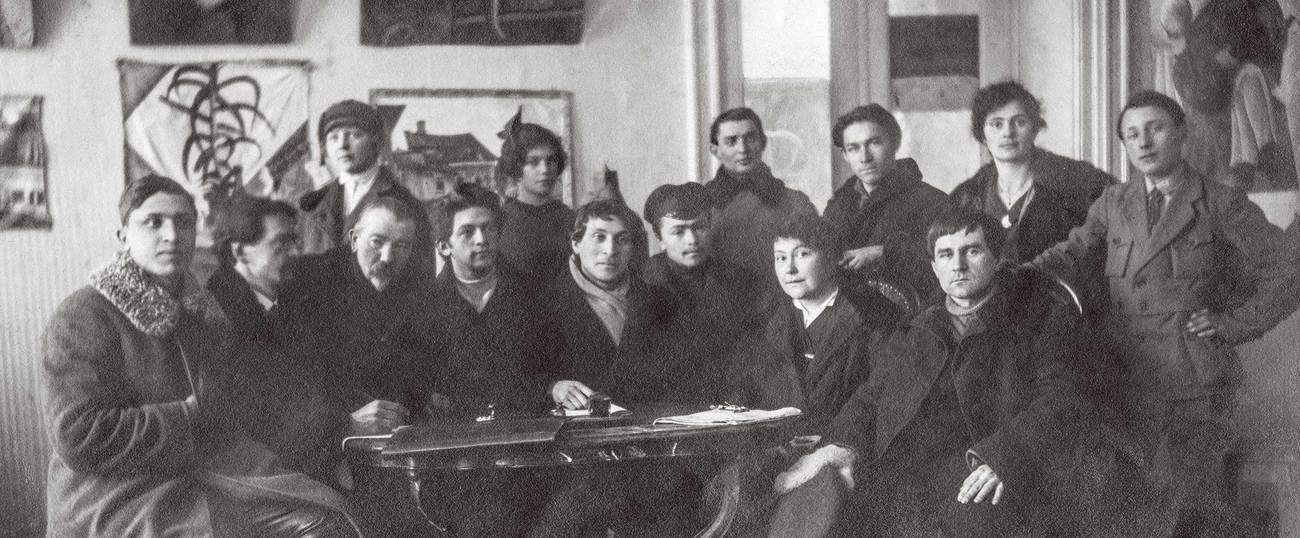

There is a frequently reproduced photograph, not on display at the Jewish Museum exhibit, of Malevich teaching in Vitebsk. The photo is a rare unposed one, in which only three of the 12 students, the ones sitting at a small, almost hidden table, are looking at the camera. One student kneels on the floor, drawing, surrounded by six other students studying the drawing in progress. None of the 12 students are looking at Malevich who is writing on the blackboard. Is this a photo of how, as another wall text has it, “the charismatic Malevich inspired his enthusiastic young students to work together and to be highly productive”? The students look enthusiastic and productive enough. But Malevich does not seem to be a particular focus of their attention.

Malevich’s so-called “charisma” lay in not having charisma. His neighbor in Vitebsk, the philosopher M.M. Bakhtin, said about Malevich: “His students, both male and female, idolized him completely and absolutely.” Malevich treated artistic style as a formal resource to serve a student’s own vision of the world. Malevich:

believed it was unnecessary and fruitless to force those with an affinity for Impressionism to do Suprematist works instead. Nothing would come of it. An artist should be doing what he feels, what he has inside of him. It is difficult to remake a person.

Discovering who that person was inside required time, thought, and the conviction that each student justified this attention. Instruction began with observation and conversation. “At first, he let everyone work as he pleased, in order to understand his psychological or physical attributes and what he was capable of.” A Vitebsk student remembered how Malevich “granted freedom to his students and never imposed anything on them.” The success of his teaching lay in his awareness that each student did have his or her own vision of the world.

In his second letter to a Moscow friend, Malevich compared Vitebsk with Moscow:

Everything says that you find yourself far from the axis around which the world turns, and that everything visible here keenly sharpens its megaphone ears and aligns its body to the voice of the center, faintly heard.

The letter continues with a metaphoric flight about the tragedy of streams that rush into rivers and lose themselves in the “cauldron of the city.”

Like Pen, Zhitlovsky, An-Sky, Chagall, and Lissitzky, Malevich knew what it was to find himself far from the world’s axis, and to be almost completely out of earshot of the center. (In Russian, the word for provinces is glush; its etymology lies in the inability to hear.) A wall text quotes Chagall: “Give us people! Artists! Revolutionary painters! From the capitals to the provinces! What will tempt you to come?”

While there is no reason to doubt Chagall’s desire for the people of Vitebsk to have an art college, the painter himself had not been tempted to go to Vitebsk: He had been stuck there. What was to have been a brief visit to marry Bella was prolonged first by the outbreak of WWI and then by the Russian Revolution. Establishing a school was a fallback after his attempts to find a position in the capital failed. In June of 1920, he finally succeeded.

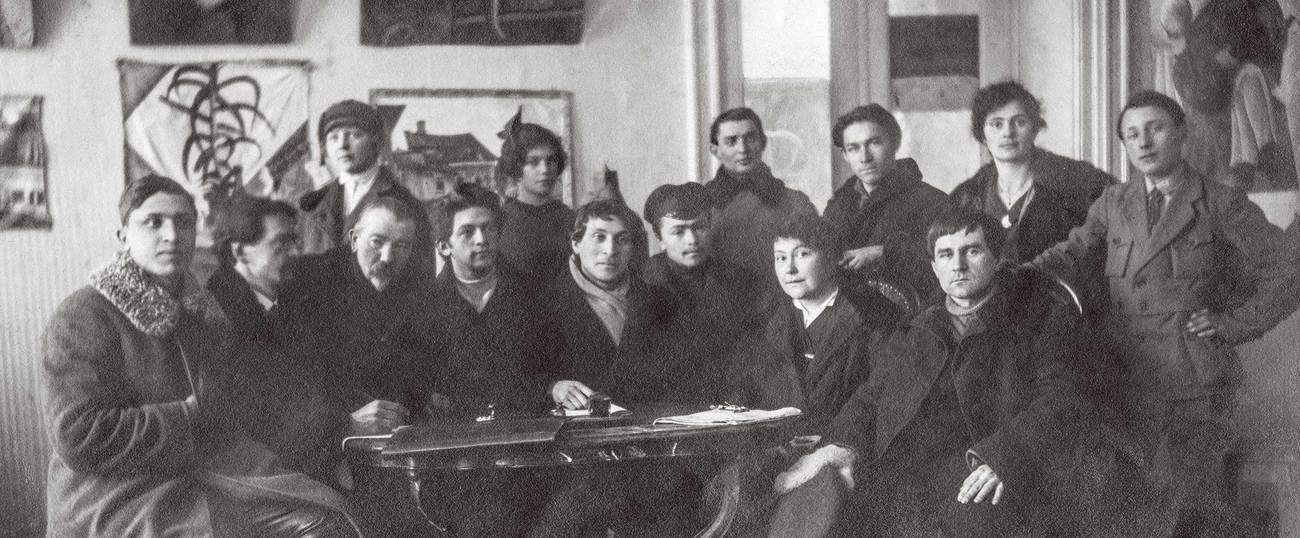

Malevich knew how provincials would contort and distort themselves to be heard and seen by the center. There is a photograph in the Jewish Museum that testifies to his success. It shows Malevich, holding a plate with a suprematist design, boarding a train for Moscow to show off what they had created in Vitebsk. The provinces were bringing their voice to the center. So remembered one of the Jewish students in that candid, classroom photograph:

UNOVIS existed in three cities “in Vitebsk (its center, insofar as its inspirer Malevich was located precisely in our city) and two others on the periphery, that is, in Moscow and some other city (I can’t remember which one it was now). We were not embarrassed that we numbered Moscow among the peripheral cities. But then, nothing at all embarrassed us. Youth is fearless and naïve.

At the entrance of the exhibit, there is a quotation from Sofia Dymshits-Tolstaya that serves as an epigraph. Recalling her astonishment at seeing “Malevich’s decorations … and Chagall’s flying people” on Vitebsk’s walls, she continues, “It seemed to me that I had arrived in an enchanted city,” and adds, wistfully, “but anything was possible and wonderful at that time.”

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Shifra Sharlin is a senior lecturer in English at Yale University.

Shifra Sharlin is a senior lecturer in English at Yale University.