The Children of Cadillac

A translated excerpt from a recent novel traces the anguished, long-buried history of a Jewish family in wartime France

François Noudelmann was trepidatious, he admitted, when we met in Paris’ fifth arrondissement this summer. Noudelmann is a philosopher, Jean-Paul Sartre scholar, a fixture of French radio, and the author of a dozen books translated in multiple languages. At the time, he was about to publish his first novel, Les Enfants de Cadillac, and he had a case of the nerves—naturally enough for someone making his first venture into fiction.

But Noudelmann had nothing to fear. Les Enfants de Cadillac, an auto-fiction sprawling over three generations, has proved a commercial and critical triumph. Le Figaro hailed the novel as “a family history of silence and fury.” Gallimard will soon release a second print run, and the novel will in short order be translated into English.

It is no surprise that the work has sustained so much interest in France, where the entry into the presidential race of far-right polemicist Eric Zemmour has refocused attention on the nation’s wartime past. Noudelmann unspools the tale of his grandfather Chaim and father, Albert. Chaim fled Lithuania at the dawn of the 20th century, finding a haven from the pogroms of the Russian Empire in Paris. He served in the French military in the First World War and lost his mind. His son Albert defended France in the debacle of the Second World War; his countrymen paid him back in spades. In Les Enfants de Cadillac, a translated excerpt of which appears below, Noudelmann reconciles himself to this heritage.

Retired from his position at the Université de Paris-VIII, Noudelmann is now a professor at New York University, where he runs the Maison Francaise and gives courses in philosophy. He rhapsodizes to me during one of our coffee klatches about an alternate family history, a counterfactual in which his ancestors had found refuge in the United States rather than France. “He might have continued on to New York,” he muses about his grandfather Chaim. “I have finished what he started.” One encounters this sentiment often among French Jews, especially those of Eastern European origins. America retains its luster for Frenchmen as the imperial center; New York boasts the status of the imperial epicenter. French Jews, fretting over the vitality of their community, often experience this midcentury idyll even more acutely. Noudelmann marvels at the assertiveness of American Jewry. “I saw them marching in a parade in Manhattan with the Israeli flag,” he says. “This would never happen in France.”

There have, of course, been setbacks and disappointments. Noudelmann mentions more than once that none of Paris’ left-wing publications have even mentioned the book’s existence—a result, he suspects, of Cadillac’s frank discussion of left-wing antisemitism. He shudders at being painted as a neoreactionary. He is far too progressive—with an egalitarian vision of education born of his past as an adolescent wastrel—and far too eclectic—an expert on Jean-Paul Sartre, a spiritual son of Édouard Glissant, an interpreter of Mishima—for such a label.

Noudelmann has also been pulled into the maelstrom of Paris’ literary squabbles, accused of a conflict of interest after he was named to the long list for France’s most prestigious literary award, the Prix Goncourt (for which his girlfriend, Camille Laurens, sits on the selection committee). The truth was banal; Laurens had in fact disclosed the relationship to her colleagues, who told her she was not obligated to recuse herself because the couple was not married. But Cadillac was nonetheless disqualified from further consideration in the contest, based on new rules barring the works of jurors’ intimates. Even-keeled as Noudelmann is, he cannot stifle a feeling of injustice. “I am incensed at what happened,” he says, “it was a prime example of trial by media, where we live by Queen of Hearts rules: sentence first, verdict afterward.”

But controversy is the wage of success, and nowhere is that truer than on Paris’ Left Bank. Noudelmann has moved on: He is in the middle of writing his second novel. —Daniel Solomon

One might call it a fortunate death: Chaim was deceased before he could be denounced. The prefect of the Gironde, appointed by the Vichy regime, had asked for a list of Jewish lunatics, and he had received it. Francois Pierre-Alype, the Pétainist official, devotee of Maurras, and fastidious collaborator, hunted down as prefect ‘Israélites’ and foreigners, handed over Resistance fighters to the Germans and, in 1942, ceded his position to General Secretary Maurice Papon, the man who would organize the deportation of Jews to the death camps. Pierre-Alype would be acquitted for his crimes in 1955 but, unlike his successor, would not have the honor of becoming a minister in Raymond Barre’s government in 1978.

But before he could be hauled onto some eastbound train, Chaim died. He died in Cadillac, alone, without Beila and Abraham, his parents, without Marie, his wife, without Albert, his son, all of whom would never come to mourn at this unmarked place. Never would they have imagined this as the last stop on an epic journey beginning in Russia and leading through the French trenches.

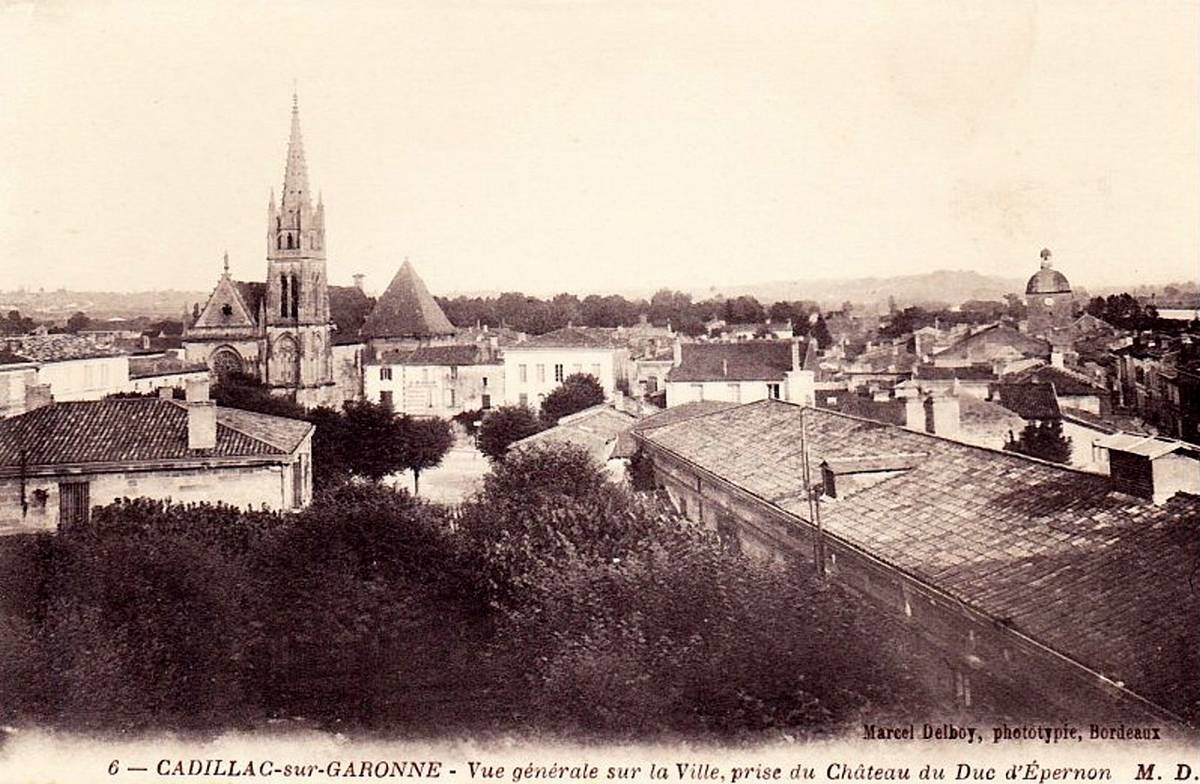

Cadillac—today, as then, a town of about 3,000—was the end of the line for his life in the asylum. Surrounded by vineyards, it boasts the placid beauty of old, walled cities: Its ramparts, their gates, the Porte de la Mer and Porte de l’Horloge, its castle—all exude a kind of sober, classical majesty. Near the town hall, under cavernous arcades, the people of Cadillac linger on the patios of cafes and restaurants, as though intent on preserving, rather than merely enjoying, the Girondin atmosphere lauded for centuries now. This impression is deceptive.

Both Cadillac’s present and its past are rife with great violence. The town’s asylum and prison possess histories that are as proximate to each other as the two buildings. The Hospice Saint-Leonard, founded in the 14th century, took in the sick, the destitute, and various pilgrims for 300 years. Then, in the 17th century, the Duke d’Epernon ordered the hospice be repurposed: From then on, it was the Hospital Sainte-Marguerite, a haven for melancholic aristocrats who needed to rebalance their humors.

The Revolution brought about a democratization of lunacy, and with it, new lunatics to the Hospital Sainte-Marguerite: commoners, people of modest means. In 1912, it became an autonomous public asylum for the insane; and, today, it is a departmental psychiatric hospital to which, in 2016, a unit for Difficult Cases was added. There soon followed a Specially Adapted Hospitalization Unit, which is to say a prison hospital for dangerous lunatics. Cadillac now is the site of lurid reports on inmates who have committed heinous crimes and whose boundless rage renders both nursing staff and prison guards impotent. Documentaries with punchy titles like France’s Deadliest Madmen often portray their subjects as carnivalesque beasts, chemically straitjacketed and capable of arousing sympathy—soon tempered by a recitation of the criminal’s gruesome deeds.

Removal from society, whether by hospital or prison, finds another instantiation in Cadillac, in a complex whose moats and high walls appear more prestigious and less menacing than the barriers around the prison hospital. The state purchased the castle of the Dukes of Epernon at the start of the 19th century and soon converted it into a girls’ juvenile hall. The nobles’ apartments were divided into dormitories and workshops, the windows tinted. The 400 young women incarcerated there submitted to strict rules of discipline and weathered cold, dank winters. They worked for 13 hours a day in silence, incurring punishments for singing or making noise while sewing, weaving, and cleaning animal hides for clothiers. The rate of suicide and fatal illness for the detainees reached epic proportions, eclipsing that of a women’s prison, with an average of 30 deaths each year.

These surreal premises, where one finds juxtaposed the vestiges of la France ancienne, replete with frescoes and sculpted porticos, and cages of wire mesh and metalwork, reminders of the woe of thousands of girls, bring me closer to Chaim. No photographs remain of him after the ’20s and I imagine him arriving in Cadillac in a bad state, transferred to this terra incognita, a far-flung province where he had never ventured. The abundant vines might have recalled for him certain areas of Montmartre.

Chaim found himself in Cadillac at the worst possible time, an era of destitution and food shortages at the hospital. Times of chaos—of wars, epidemics—tend to exacerbate class distinctions, to make them more acutely felt, and thus remind us that the insane constitute the lowest stratum of society. Many people—the elderly, cancer patients, convicts—take precedence over the insane; and the insane are consequently sacrificed just as soon as society is forced to prioritize. These are the victims of dominant utilitarianism: They count less than others do. Why feed these useless eaters—these hungry, costly, intractable burdens? When it comes time to cut staff and ration food, no one much cares what happens at the psychiatric hospital. With barely anyone left to care for them, with barely any food to nourish them, the insane were shunted to the side—even if, like Chaim, they had been decorated for military service.

Famine killed tens of thousands of mental patients in France: In the decades since this silent disaster, it has been amply documented by historians, though just how intentional this sacrifice was is the subject of some debate. Investigations into the food shortage have been undertaken at Cadillac, and blame has been assigned not just to the German occupation—though certainly that was a factor—but to the management of the hospital as well. Patients’ food and clothing were often expropriated by staff. They stole with impunity. No one listens to the words of the mad.

In Cadillac, patients died at the rate of one per day. One internee, appalled by what he saw, wrote the following report:

Every day, when soup is served, some [patients] escape the supervision of the nurses on duty, rush behind the kitchen to the pile of vegetables, or even the heap of vegetable peels and kitchen scraps, and stuff their pockets … with what they find. We have seen some pluck sparrows and eat them raw. Another fished out a drowned rat from the cesspool and feasted on it. Others join together to kill and skin a cat.

The Health Ministry conducted an investigation after complaints were filed, and its findings reported systemic abuse throughout the entire Cadillac asylum hierarchy, from administrators to caregivers. Patients’ lives grew ever more nightmarish amid the corruption, graft, and falsified reports; and at night, they slept in dormitories where it was less than 40 degrees Fahrenheit. Dinner was rutabagas floating in clear water and a lump of sugar. The staff stole dozens of pounds of meat—and bread and coal and tobacco and clothes and blankets, too.

Chaim died on March 21, 1941, at 9:50 a.m. He was 50. The asylum’s register records his cause of death (“cachexia”) and his original diagnosis (“mental degeneration, schizo-paranoia”). More common terms for cachexia include starvation, malnutrition, and weight loss through atrophy of muscle, fat, and bone. The nosography of the era lists common disorders at Cadillac—senility, childhood regression, idiocy, dementia, epilepsy, bedsores—but like three-quarters of Cadillac’s lunatics, Chaim died of starvation. But of course Chaim had already seen himself die little by little—one hopes that he had lost his mind, that he was no longer conscious of the slow dissociation of body and soul. He sank into decline and demise in this base and sordid bedlam, after 22 years of confinement. He had lost his mind in the First World War, dosed with mustard gas as a French soldier, and lost his life during the Second World War, before France’s collaborators could have him exterminated.

The asylum buried its dead in its own cemetery. Four burial grounds of this sort, now facing the prospect of disappearing beneath new buildings, have been identified in France. The mass grave at Cadillac is now called the “Cemetery of the Forgotten”: about 90 rows of 10 to 12 graves each, rearranged over time as more recent burials required. Chaim was buried there.

By the time he died in 1941, a surplus of the dead resulted in bodies being buried two or three to a coffin, in shared shrouds. Thus, at a depth of 5 feet, their corpses were superimposed on one another, awaiting decomposition. It takes six to eight years for bones to be cleaned of their flesh, but we cannot imagine the insane who died during the war had much flesh in the first place. Once fully reduced to skeletons, the bodies were moved to make room for newer ones. The bones of the now-unburied dead then went to an ossuary. The gravedigger had to organize the ossuaries, avoiding the old bones, especially femurs and skulls, and choose where to deposit the new remains.

Chaim’s body followed the steps of this peculiar funerary rite in the process of decomposition, the corpse interred directly in the earth, placed in the potters’ field of deserted madmen, no doubt lost among the sacks of bones that we today call “the outcasts of memory.” This former soldier, naturalized as French 14 years before his death, released from military service obligations on Nov. 10, 1940, only shortly predeceased most of Europe’s Jews. He died as a mental patient, not as a Jew: He had avoided Zyklon B because he had, long before, been sickened by mustard gas. He had not been burned, had not become ash settling into the Polish soil. His gaunt remains had disintegrated on the French ground he had chosen, enriching the soil of a region whose terroir is celebrated for the wine it produces. He might have flashed an ironic smile at this “burial,” which rendered indissoluble his francité, left him enraciné.

The carré des fous at Cadillac is strewn with gravel set over uneven ground, rows of rusted iron crosses, sometimes topped by tin plaques bearing the name of the deceased, a number, or a date. Chaim’s remains had sat under one of these crosses, even though the institution’s registry paid enough heed to describe him as an “Israélite.” These crosses erased him even more; he disappeared under their mercy in the same way that the victims of Auschwitz did under the crosses erected at the camp by Carmelite nuns. Jew, Muslim, atheist—no matter—the mental patient ended his existence beneath a cross. The ones at Cadillac, first made of wood, were replaced in the ’50s by iron ones. These rusted on land forgotten, save for the occasional plaque or urn left by mourners. Chaim might not have cared about rotting under a cross: He had absconded from the Hasidic sect in Lithuania into which he had been born and probably had no more illusions about the hereafter.

He had not been interred in the section of the carré dedicated to veterans. Would that have mattered to him? A part of the cemetery is reserved for “the brain-mutilated” of the First World War, containing around 100 graves, 60 of them anonymous. One plaque was inaugurated there in 1937 by “the veterans of the Gironde” to “remember their brain-wounded comrades, victims of the Great War.” Another erected in 1956 features a tribute from “the veterans and prisoners of war to their comrades.” Chaim is honored by neither of these plaques, as if the France of the Second World War sought to remind him that despite his naturalization in 1927 he remained a Jew.

My father, Albert, never went looking for his father Chaim. He never honored the grave of his mother. He told me he could not stand cemeteries, the gravestones left him unmoved. How ridiculous, he lamented, to stick rotting bodies in otherwise pristine grounds. Albert, the son of a war veteran and naturalized French citizen, left the dead with the dead and fixed his gaze on the horizon. He was talkative and made those around him laugh. He was praised for the gift of gab, but on a deeper level he was taciturn.

He never spoke about the rift in his life, the period that cleaved it into tidy, discrete sections, the opaque wall between “before” and “after”: the years from 1937 to 1945. During our life together and even after, he remained silent about his past, never even alluding to it. No one would suspect it might have left an indelible mark on him if not for his hearing aid—a souvenir of the loss of his ear on the battlefield. He was not interested in films or books about the war, maybe because he did not like pathos, maybe because these stories are not easily told, impossible to summarize in terms of experience, event, or trauma. Such stories, even if they are told by witnesses, humanize abominable experiences, inhuman experiences, experiences which exist on the very margins of language itself. They are both exceptional—it is not every day that one lives so close to death—and ordinary, for so many Jews share them. He did not know, at the time, that literary critics would turn the “camp story” into a literary genre—a genre antisemites would categorize as an arm of the “Holocaust industry.” Most survivors, though, did not recount what happened to them: They remembered how few people wanted to listen when they were liberated. Primo Levi’s masterpiece, If This Is a Man, was written at the end of the war and took nearly a decade to find a publisher. So the Jews did not valorize their suffering.

We had already grown distant when I wanted to force the subject. I wanted to look for the corpse beneath the parquet floor of my father’s well-ordered life. I could not accept the word “resilience,” with its crushing reassurance. I still do not know why he agreed to break the silence, so assiduously controlled as to go unnoticed by all around him. Did he want to recover our lost intimacy? Did he seek to reconcile himself with a part of his existence which, heretofore, had been carefully repressed?

He delivered the story in a single stream, uninterrupted, for 10 hours—speaking once and for all, for the last time, the little tape recorder he had given me for my 10th birthday capturing his words all the while. And, for 40 years, I never thought of transcribing it, much less transmitting it: This was a confidential gesture, made from a father to a son. I never wanted to share it. I wanted to preserve the exclusive rapport I maintained with him since childhood. Perhaps I wanted to avoid linking myself with this experience—perhaps I was anxious to maintain, in my own way, the apparent harmlessness of a clandestine past.

My father was taken prisoner, along with more than a million French men under arms, amid the debacle of May-June 1940. On about 100 acres, surrounded by a double wall of barbed wire, ringed by watchtowers, he and somewhere between 50,000 and 75,000 other people were confined. Hygiene was disastrous: With no showers, with inmates standing next to each other, on wooden logs, relieving themselves into a trench below, how could it be otherwise? Modesty was impossible in the prisoner-of-war camp, impossible for all; this was the communism of shit.

I wanted to look for the corpse beneath the parquet floor of my father’s well-ordered life.

Inequalities remained, though, between nationalities: The barracks formed small villages, in which the same language was spoken, and hierarchies existed between the Poles (disdained), the English (not disdained), and the French (treated well enough, but not as well as the English). When Philippe Pétain delivered his speech on June 17th announcing the armistice, it was broadcast especially for the French, via the loudspeakers surrounding their quarters. The Marshal had made to France “the gift of his person,” and in “honor” opened the door to collaboration with the German victors. My father, militant trade unionist that he was, knew Pétain had always been associated with anti-republican movements—he had been French ambassador to Franco’s Spain—and was, consequently, less than thrilled. But most of the prisoners wept with emotion, hearing their patriarch address them in his sour voice. They did not believe they had been betrayed—in fact, they believed they would be home very soon indeed. In spite of his maverick spirit, he might have led the life of an ordinary prisoner of war. He might have, if not for what happened—if something had not upset everything he believed until that point.

The Germans inspected the barracks regularly, making selections and thus establishing three categories: the French, the Bretons, and the Jews. They took to threatening prisoners with sanctions if they did not denounce the Jews among them, and promising rewards—usually double rations of food—if they named names. The captors called the roll every day, and every day they demanded the names of the Jews.

Disaster is inevitable. Whether one prefers to call it a psychological fact or a statistical one, it is a fact all the same; and it was a fact which my father failed to anticipate. He never felt he belonged to a distinct group among these, his comrades. But a French prisoner pointed him out to the Germans all the same, and just like that, two soldiers appeared and pushed him out of the line. Four other Jews were denounced, too—five rations, total. My father did not know the man who gave him up. The rat must have seen it in his body or name. And suddenly, for the first time, my father felt like a Jew—he, who never practiced the religion, who had never been called “dirty Jew,” whose friends and whose wife were not themselves Jews—my father felt like a Jew. He had known he was Jewish, but the adjective had now become a noun: He was now a Jew, a Jew in substance, in being. The word fell on him, cruelly pronounced, in French and in German—Jude—an imprecation that banished him not just from the community of Frenchmen, but of all men. He was an untermensch; he had been pushed out of the line.

The repercussions of his selection were unknown to him. He knew nothing of Buchenwald, the camp created just three years earlier, much less of Auschwitz, which had then just opened. The most he knew is that the Germans were hunting down Jews back in Germany—he had seen the refugees in Paris. He could not imagine that the hunt would engulf all Europe. He was, in that moment, torn between hatred and despondency. He wanted to find the son of a bitch who had denounced him, who had received a quarter loaf of bread rather than an eighth, a second ladle of prison gruel. Hunger and fear had overcome any sense of solidarity. He felt an immense solitude, an almost metaphysical solitude, felt it sweeping him away: He was alone, alone in the world; he felt no sense of kinship even with his four fellow outcasts. He remembered the old joke, which he had first heard around the time the Nazis came to power in Germany:

Two Jews are walking down the street. They see two SS officers walking toward them. The first Jew wants to run off as fast as he can, but the second tries to reason with him: “Come on,” he says, “it’s an even match: two of them, two of us—what’s the problem?” “An even match?” says the first Jew. “There’s two of them, and we’re all alone!”

His banishment was immediate. The five denounced Jews had to leave the French barracks immediately. He was taken to another barracks, at the other end of the camp, where he found himself in the company of a dozen other Jews who had already been spotted. Humiliations followed: He was stripped naked and his head was shaved—Jews were reputed to be vectors of disease, carriers of lice. More degrading still, he became the slave of his former comrades, ordered about by them at will. He and his fellow outcasts were made to do all the drudgery, the hauling of heavy equipment, the cleaning of excrement. When he passed French prisoners, he heard them call out to him: “Hey, Jew!” Often, French noncommissioned officers would commandeer a Jew to act as their factotum.

In the aftermath of the French defeat, the population in the POW camp had swelled, and consequently, Germans had delegated authority inside its walls. Each barracks was administered by an internal police responsible for keeping order and interacting with the Germans. This system made petty tyrants of a number of corporals who took advantage of their servile power. Even subalterns have subalterns, and the Jewish camp was the camp of the camp, where the “bigshots,” “wicked enough to do so,” found slaves on which to foist the dirtiest jobs.

How to explain the difference between those who resign themselves to their fate and those who actively resist it? My father understood he had to escape his position as scum-of-the-Stalag at all costs. He knew the only other choice was to wind up dead, and he did not want to die. So was it a question of character, then? Of education? Of foresight? In any case, he tried to convince his fellow slaves to help organize their escape, but they were unwilling. He found himself alone.

The systemic extermination of all European Jewry had not yet begun, but still, my father had a feeling misfortune would not spare the Jews under the Nazi regime. His goal was simple: eliminate his identity. He no longer wanted to be, “Hey, Jew!” To escape that fate, my father had to rid himself of his name—to burn his papers and thus return to the community of peons with the right to live.

Paradoxically, his good fortune lay in the chores he was given. These took him out of the camp to unload trucks, or to transport trees. He imagined the scenario several times during his daily outings and then, one day, at dusk, he did it: Despite one last overture to his fellow inmates, Jewish or otherwise punished, he ran away alone.

While he was carrying logs in a team of three men, transporting the timber from the forest to the truck, he took advantage of the growing darkness and the guard’s reduced vigilance to flee, concealing himself in the night of trees. He ran blindly between the huge firs—between beeches, oaks—and he only stopped when he was exhausted, when the night was truly dark.

As a Parisian, he had never really enjoyed sleeping in the forest or in the meadows, but he much preferred the company of nocturnal animals to that of diurnal Jew-hunters. He took a box of matches with him, and with that, he set fire to his military papers. Then, he buried his soldier’s badge. With no other plan to speak of besides this tiny fire, he lay down in the moss; and, though it was summertime, he was cold.

He had to get it through his head: He was someone else now. He was to be reborn in this Silesian humus, his only witnesses mushrooms and crawling insects. He was to forget his name, his parents, his wife. He would never answer to his surname again. He would be a new man, a Frenchman, with many French generations behind him, ancestors buried across the country, his blood red and French as wine and steak. His name would be Garnier.

Many years later, in the winter of 2008, I was living in Paris’ 13th arrondissement. Large demonstrations often passed by on the Boulevard Arago, in front of the Protestant seminary and Santé Prison. I took part, sometimes—especially in those days of the Ministry of National Identity, which naturally enough recall unpleasant memories.

Foreign policy rarely mobilized French protesters, but Palestine was an exception, especially since that year’s invasion of Gaza by the Israel Defense Forces, which came on the heels of thousands of rockets being fired from the Hamas-ruled enclave. Every week, tens of thousands of demonstrators took to the streets to denounce what they saw as a wildly disproportionate response on the part of the IDF. On that particular day, I could have joined the procession if it had not been for my preference to march with the activists of Peace Now, an organization which supported a two-state solution. But I made my way to the rally accompanied by a friend who was sympathetic to the cause. We had made the decision to stay at the procession’s margins—we simply could not find a banner which felt compelling enough to march under.

We sensed immense ambient anger that day, anger distinct from that which animates even violent demonstrations at which the euphoria of solidarity propagates a kind of rebellious joy. A murderous impulse was spreading among the sloganeers. Without quite being able to believe our ears, we heard it: “Death to the Jews!” It was not a lone voice, either—no: It was a dense, collective howl.

The crowd was made up of men. Some were dressed in green, the color of Hamas, and they were bracketed by the familiar red flags of such protests, with their acronyms and party slogans. On the Boulevard du Montparnasse, an auto-da-fe ensued as a frenzied crowd burned the flag of Israel, with its Star of David, as well as assorted texts and effigies. I asked my friend if he had heard the words I had, but it seemed he all of a sudden wanted to leave: He was embarrassed, as if he had suddenly wandered into the screening of a pornographic film. I insisted that he acknowledge this incitement to murder, and I understood then what denial meant; his refusal to hear resembled a deliberate loss of consciousness before an inconvenient reality. Around us, some of the faces we saw were pale—they showed the fear caused by these criminal words. An Arabic teacher later confirmed that the slogan had been repeated, word for word, all along the Boulevard Port-Royal, where he lived. A neighbor confided to me in a low tone of dismay: “Have you heard? It’s just disgraceful!”

Something previously unimaginable had crept into the ears of Parisians, bringing back an old calumny thought to have died years ago. I thought of my ancestors, Noudelmanns and Friedmanns, who had to wear the yellow star in a Paris where these very same calls to murder covered the walls, the windows. I saw my aunt and my cousins showing me the badge of infamy, kept in a shoebox, telling me the reactions it elicited in passersby, who either gave them hard looks of scrutiny or averted their eyes, and of their strategies to prevent encounters with German soldiers or Vichy militiamen. Their anxiety was closer, suddenly—more tangible.

Thus, 65 years later, on the boulevards of the capital, one could hear the scream of Jew-hatred once more. And it did not matter whether these irascible men were French or not; they were surrounded by recognized activists and enjoyed their tacit understanding, their sympathy, even. They had sounded the bugle: The hunt could begin again.

Translated by Daniel Solomon and Ben Zitsman

François Noudelmann is a French philosopher, professor, and author. He is currently a professor at New York University.