The City Without Jews

A chillingly prescient 1924 Austrian film gets new life—and ‘incandescent’ relevance—in a miraculous Blu-ray restoration

The social scientist and cinephile Siegfried Kracauer spent most of World War II translating and interpreting Nazi propaganda films for the Museum of Modern Art Film Library. Calling up more congenial memories of German cinema, he also rewound in his mind the films he had seen during the glory days of Weimar cinema from 1920 to 1933.

Yet Kracauer, a Frankfurt School alum and German Jewish refugee, began to detect something “macabre, sinister, morbid” in the hallucinatory dreamscapes that had spilled forth from the Babelsberg Film Studio, the legendary art-factory that gave Hollywood a run for its money. Lurking in the Expressionist set design, elongated shadows, and unchained camera shots was a haunting vision soon to be made real by the Third Reich. In his famous study From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological Study of German Film, published in 1947, Kracauer drew a straight line from the dark projections on the Weimar screen to the unholy desires locked up in what he called “the German soul”—a death wish just waiting to be fulfilled.

A classic instance of 20/20 hindsight, Kracauer’s filter is ahistorical, presentist, and downright mystical. It also impossible to shunt aside when certain images from Weimar cinema unspool like a grim prophecy, almost a blueprint, for what lay ahead. Think of the scene in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927), when two columns of workers march robotically into the yawning maw of a fiery furnace. “Moloch!” screams the intertitle, invoking the pagan god who demands human sacrifice.

So, to look at The City Without Jews (Die Stadt ohne Juden, 1924) nearly a century on is to be caught short by the very title and be chilled by the inevitable flash forward. The sight of an exiled Jewish population—bedraggled hordes, weighted down by all their worldly possessions, shoved on to trains for relocation to the east—might be from newsreel footage that has not yet been shot. The film is silent but you can almost hear the guards barking: “Raus!”

Newly released on Blu-ray by Flicker Alley, the outfit dedicated to the preservation of motion picture treasures (and that is itself a national treasure), The City Without Jews was a minor blip in its time that today radiates an intense incandescence. It was made in Austria—technically outside the borders of Weimar Germany, and not part of the Greater Reich until 1938—but Hitler’s birthplace was seldom out of sync with what was happening in Germany or, for that matter, with the sentiments of its native son. Directed by Hans Karl Breslauer, a Viennese actor turned filmmaker; scripted by Breslauer and Ida Jenbach from the novel by Hugo Bettauer; and featuring the future star Hans Moser, the film sends out eerie portents in every frame and screen credit. Breslauer later turned to writing and, despite his most famous screen credit, joined the Nazi Party in 1940; Moser angled his popularity as one of Hitler’s favorite actors to save his Jewish wife; and Jenbach died in a concentration camp.

The story is set in the mythical Republic of Utopia, a troubled land that belies its name: Unemployed workers clog the streets demanding jobs, rampant speculation and hyperinflation roil the economy, and the wastrel superrich drink and debauch while the proles suffer and starve. “I’m telling you the Jews are responsible for our misery,” a demagogue predictably concludes. “The only solution is to expel the Jews.”

It is hard to see why: The Jews seem mainly interested in practicing their faith not hustling the Christians. In a modest synagogue, they worship peacefully, clutch the Torah reverently, and in general behave like model citizens. A wealthy burgher is even glad to give one enterprising young Jew, Leo (Johannes Rieman), the hand of his gentile daughter Lotte (Anny Milety). There’s not a greedy Shylock or scurvy Fagin figure in sight.

To the fanatical anti-Semites in the Utopian parliament, none of this matters. Though the chancellor of Utopia (Eugen Neufeld) is an empty suit who has no particular animus toward the Jews, he heeds the voice of the people, or at least the loudest and most xenophobic voices. In a metaphor that sounds more sinister now than it did then, the Jews are likened to a rose chafer—an insect that the gardener must eradicate if he wants his rose bushes to thrive. As an added incentive, a wealthy “American anti-Semite,” referred to as “Mr. Huxtable”—presumably a stand-in for Henry Ford—pledges $100 million in credit to Utopia if it will exile its Jews.

In short order, the Utopian parliament votes to banish the Jews, with the provision, more open-minded than the Nuremberg Laws, that “baptized Jews of the second generation will be declared Aryans.” (American audiences would have been familiar with the crackpot racial designation from its use in D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915)—and in KKK leaflets.)

“Ausgestossen”—cast out—reads a stark, single word intertitle. The Jewish families of the city, rich and poor, healthy and infirm, are rounded up and paraded out of town through the snow. There are tearful farewells at train station platforms. In director Breslauer’s most striking sequence, we see a night-for-night shot of the exiles trudging along a snowbound road, their breath condensing in the frigid night air. Old men fall on their knees and beseech God for mercy. The Jews are being sent to Zion—Palestine—but no one viewing the film today will think that is their destination.

Utopia celebrates the forced exodus, but not for long. Without the Jews to take care of business, the place goes to hell. The cultural amenities—food, fashion, and theater—are also hit hard. “When you expelled the Jews, you banished prosperity as well,” laments a rueful Utopian.

In a plot machination too convoluted to detail (short version: Leo returns in disguise to win back his gentile fiancé and overturn the deportation decree), Utopia opts to be Judenfrei no more. Like the wrap-up to a bizarre screwball comedy, the squabbling couple realizes they were made for each other. Jews are simply too valuable a civic resource to dispense with. “The end of the anti-Jewish policy sparks a miraculous economic recovery,” declares a joyous intertitle.

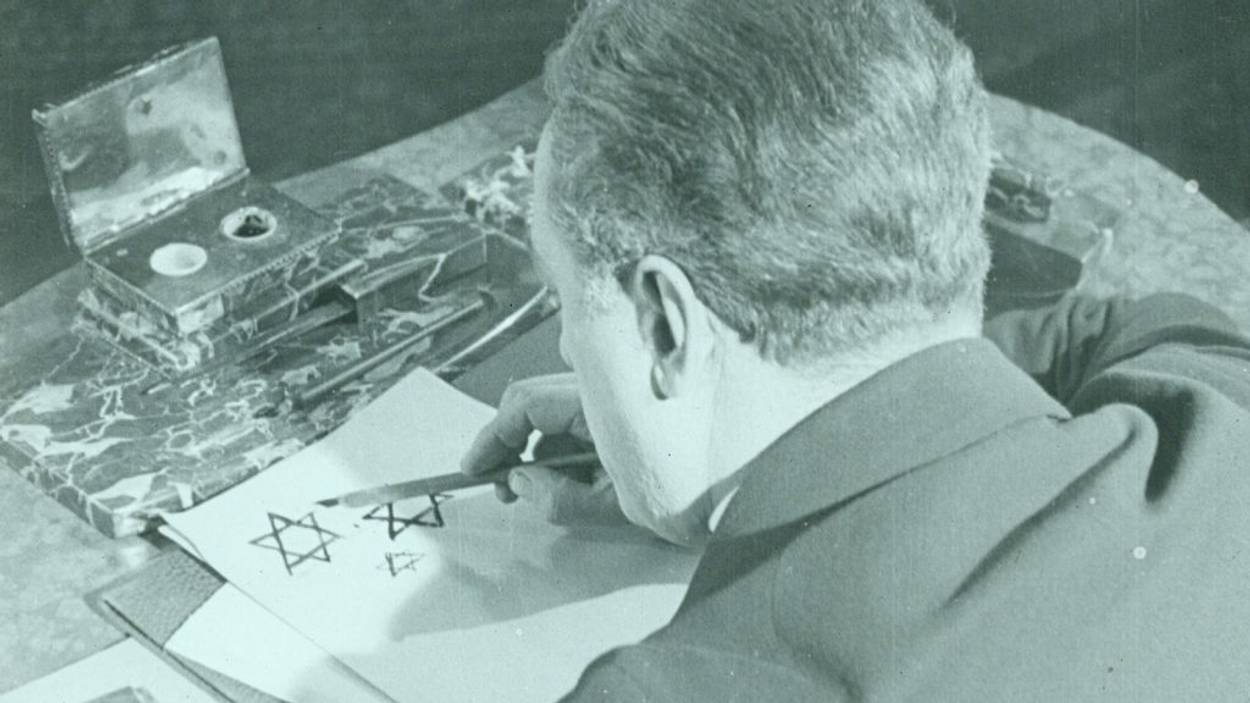

A coda delivers a nice piece of poetic justice. In the single truly Expressionist interlude in Breslauer’s otherwise realistic milieu, a virulently anti-Semitic politician (Moser) winds up in an insane asylum, having been driven bonkers by his obsessive fixation on the Jewish Other. The set design of his cell is straight out of the film that initiated the Weimar renaissance, Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920): Off-kilter walls press in on the madman and stars of David decorate the floor and his misshapen chair. The pathology of anti-Semitism has claimed another victim: not the Jew this time but the anti-Semite himself.

A film whose narrative both celebrated Jews as premium fuel for the engine of prosperity while trafficking in the ripest of medieval stereotypes was bound to stir up mixed feelings in the group it was allegedly flattering. “A species of self-patting on the back which is just as harmful as the cheap prejudices of semi-brute minds,” scoffed the literary critic Isaac Goldberg, commenting on the book.

Yet the project was certainly conceived with the best of intentions. The source novel was the work of Hugo Bettauer, a prolific Austrian novelist, playwright, and journalist, who wrote Die Stadt ohne Juden in 1922 to satirize the vulgar anti-Semitism percolating in the beer halls of Vienna and Munich. The conceit hit a cultural nerve: In Austria and Germany, the book sold over a quarter of a million copies in less than a year and went through 45 printings.

Not everyone was a fan. On March 10, 1925, in Vienna, Bettauer was shot by a Nazi dental student named Otto Rothstock who mistakenly thought Bettauer was a Jew; he died 16 days later. (Though born a Jew, the author converted to Protestantism, a distinction without a difference to his assassin.) Rothstock objected to the “pernicious influence” of Bettauer’s “erotic writings”—namely, the interreligious love story in the novel that encouraged the pollution of the Aryan bloodline. Rothstock beat the rap on an insanity plea.

Propelled by the controversy, the novel was translated into English and issued in America in 1926 by the Bloch Publishing Company as The City Without Jews: A Novel of Our Time. The theme, wrote translator Salomea Neumark Brainin, could not have been better conceived by “the most rabid Ku Klux Klansman, Hakenkreuzler, or anti-Semite”—the italicized coinage being a reference to the symbol already associated with the Nazis, the swastika.

The film version did not reach American shores until June 1928, first in Chicago and then in its natural market, New York. “I cannot imagine a place this side of Jerusalem where it would go better,” joshed a friendly newspaper editor. “The book tells of the plight that befell a great city because of a law expelling all Jews. Such a law in New York would leave nobody there but the police force.”

The film was imported by Mike Mindlin, proprietor of the Fifth Avenue Playhouse in Greenwich Village. Mindlin was a former Broadway producer who in 1926 took over the 285-seat theatrical venue and converted it into a motion picture theater specializing in revivals and German imports. The house was so successful he opened up branches in Brooklyn and Chicago. Mindlin was nothing if not eclectic in his cinematic affinities: He went on to direct the pioneering skin flick This Nude World (1933) and the docudramatic Hitler’s Reign of Terror (1934), the first American-made anti-Nazi film.

The City Without Jews was slated to open on June 30, 1928, but three hours before the screening Mindlin got word that it had been denied a license by the Motion Picture Division of the Education Department of the State of New York, commonly known as the New York Censor Board. The board was composed of three politically connected women. The head reviewer was a Brooklyn matron named Mrs. Sally McRee Minsterer; second in command was a widow and former film editor, Mrs. Helen Kellogg; and last was a pretty 30-year-old, Mary Farrell (who confessed to wearing eyeglasses but “for reviewing only”).The women were unanimous in their belief that “the entire picture is derogatory to Jews.” To substantiate the decision, they cited 26 incendiary intertitles that “incite to crime through race prejudice” and “tend to corrupt morals.”

Mindlin was blindsided because the film had played at his Chicago Playhouse to good business and with no trouble from the notoriously hidebound bluenoses in the Windy City. “The City Without Jews was passed by the Chicago Board of Censors without a single deletion,” Mindlin protested, playing the civic chauvinism card. “Certainly, if Chicago, which is less cosmopolitan than New York, can withstand the shock of seeing the film, New York can.” The Fifth Avenue Playhouse, he pointed out, was not a theater for general patronage but a small specialty house catering to a niche audience of serious-minded filmgoers—the kind of venue that would later be called an arthouse.

Overseeing the New York Censor Board was Dr. James W. Wingate, a prissy middle-aged bachelor who had the authority to overrule the three-women board. After some careful thinking, Wingate overturned the decision of the women. “I see no reason not to pass this picture with a few changes in the titles,” he said. “Nothing in the action seems derogatory to me.” He made 11 eliminations and rephrasings, all in the intertitles, all toning down the popular animus against the Jews. For example, the statement “Harassed by poverty the populace take up the cry, `Throw out the Jews,’” became “Harassed by poverty, the radicals take up the cry, `Throw out the Jews.’”

Wingate’s edits also sought to distance the fantasy from the present. A title card was inserted that set the action 50 years in the future—to 1976—and that renamed the nation Ventria (perhaps in deference to New York’s history as a safe haven for utopian communities). He also told Mindlin to eliminate the taglines printed on the advertising poster, which read: “Citizens of Ventria! Arise before you are destroyed altogether! With the Jews you drove out prosperity, hope of future development. Accursed be the demagogues who misled you!” Wingate insisted the exclamatory prose be changed to the clunky admonition: “To be progressive, a community must welcome all peoples who can make valuable contributions to life.”

Wingate cleared the film for release on July 7, 1928. Mrs. Minsterer stubbornly disagreed with her superior. “The theme was objectionable,” she insisted. “When you see the picture, you will see why.”

For his part, Mindlin had little option but to comply with Wingate’s demands. He got sort of the last word by prefacing the film with a title-card prologue of his own that protested the intrusion of the censor board into a “a great social drama.” In lobby advertisements, he hailed The City Without Jews as “a challenging motion picture produced from the fantastic novel.” To sweeten the lure, Mindlin added two on-theme attractions to the bill: the vintage Charlie Chaplin two-reeler The Pawnshop (1916), and a travelogue short, The New Germany (1928).

Nothing helped. The City Without Jews played to dismal business and dreadful reviews. “Essentially the picture is fourth rate,” (Billboard); “one of the most fatuous productions imaginable” (New York Times); and “plotless, miserably acted, and obviously undirected” (Brooklyn Standard Union) were the verdicts of the critics who bothered to review it. “Hugo Bettauer, author of the book from which the film is adapted, is said to have been shot for writing it,” continued the harsh notice in the Brooklyn Standard Union. “The assassination was too late.”

After a mere two weeks, Mindlin pulled The City Without Jews and replaced it with The Way to Strength and Beauty (1925), an “educational” documentary about a more exploitable German obsession: the vogue for outdoorsy, clothes-optional activities that included titillating shots of nude models and athletes. The City Without Jews vanished down the memory hole.

Except, that is, for the Austrian Film Archive, where The City Without Jews was always considered “one of the most sought-after lost films in Austrian film history.” The story of its rediscovery and resurrection is told in the bonus material on the Flicker Alley edition. In 1991, a Dutch print surfaced—but it was fragmented and incomplete. Then, in 2015, in one of those freak occurrences that film geeks everywhere thrill to, a nitrate print with the missing footage was found in a flea market in Paris. A crowdfunding campaign then raised the money for a complete restoration, including a beautiful, period-appropriate musical score written and performed by pianist Donald Sosin and Klezmer violinist Alicia Svigals.

Oddly, Siegfried Kracauer made no mention of The City Without Jews in From Caligari to Hitler. He must have missed the film during its original run in Frankfurt in 1924. Not that he needed more evidence to confirm his psychological profile. “It was all as it had been on the screen,” he wrote in the final notes on his extended session with Weimar cinema. “The dark premonitions of a final doom were also fulfilled.”

Thomas Doherty, a professor of American Studies at Brandeis University, is the author of Hollywood and Hitler, 1933-1939 and Little Lindy Is Kidnapped: How the Media Covered the Crime of the Century.