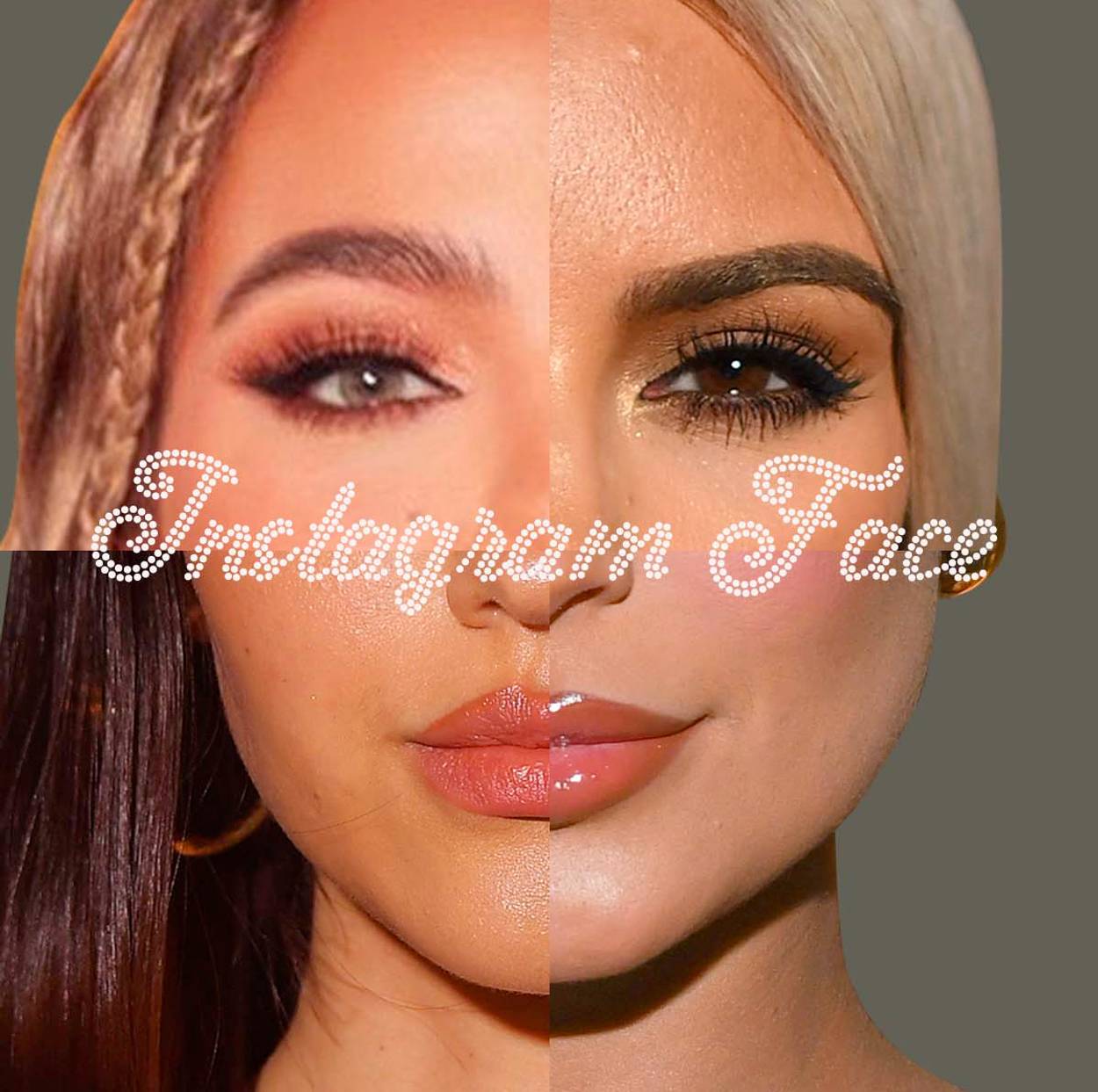

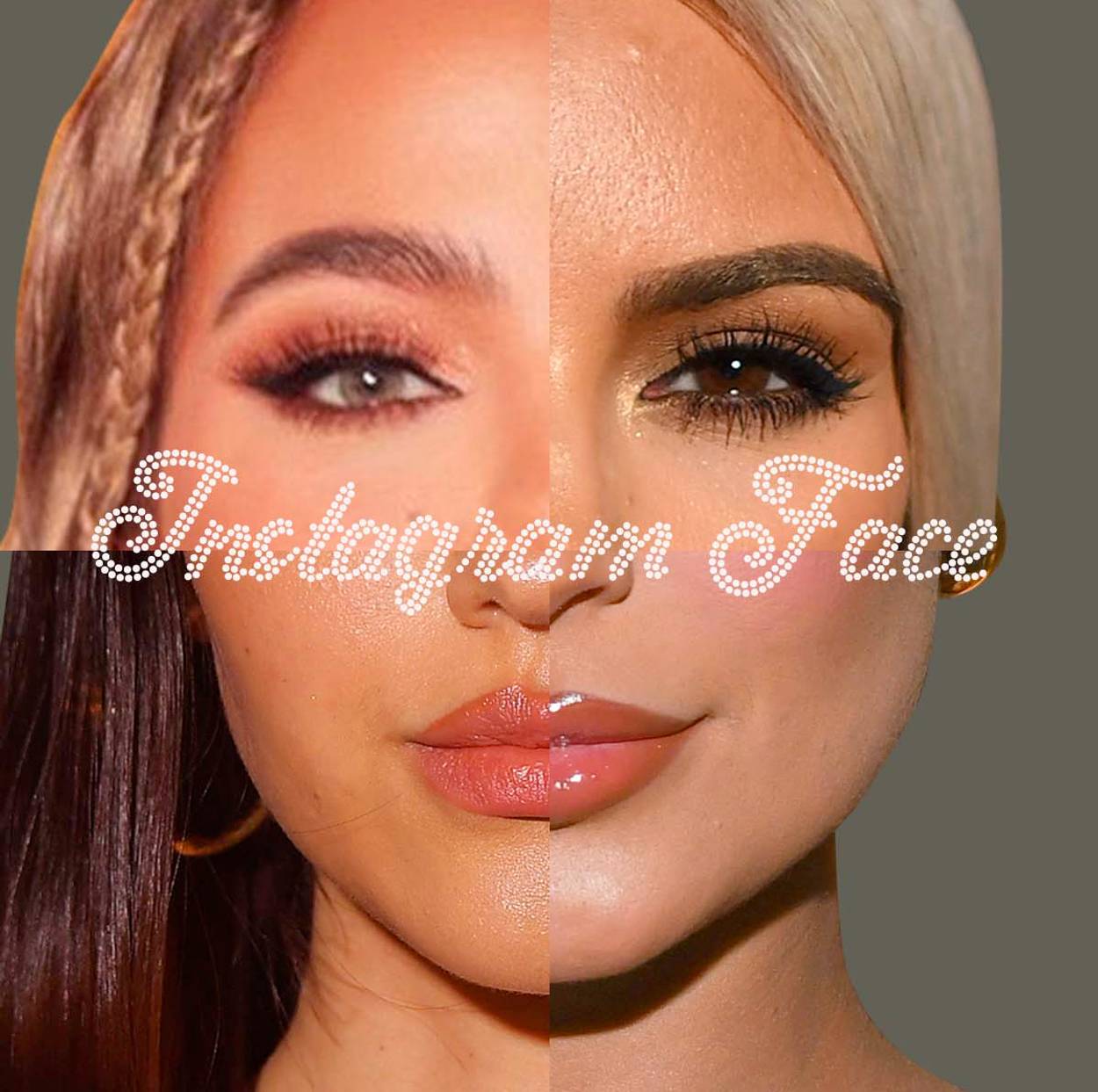

The Class Politics of Instagram Face

Plastic surgery is changing, and for an obvious reason: When in history have rich women ever wanted to look like regular ones?

At a restaurant in Miami last month, dining beside my husband, I examined the women around me for what people refer to as Instagram Face. The chiseled nose, the overfilled lips, the cheeks scooped of buccal fat, eyes and brows thread-lifted high as the frescoed ceiling. Many of the women had it, and thus resembled each other. But not all of them. Not, for example, me.

Critics call this trend just another sign of our long march toward a doomed, globalized sameness. A uniform suite of cosmetic procedures, popularized by social media, apps and filters, accelerated by both natural insecurity and injectables’ dropping costs. One by one, they hint, women will give in and undergo them. Until we all look identical, just like our restaurants do, and our hotels, and our airports, in our creep toward homogenization which we’ve somehow mistaken for a worthwhile life.

They’re wrong, because in their focus on uniformity, they’ve forgotten the premise of cosmetic work in the first place. Distinction. Good face, like good taste, has a direction: downward. The success of Instagram Face, its ubiquity, isn’t the start of cyborg aesthetics. It’s the end of it. Because what might save us from such apocalyptic beauty is something almost too ugly to say out loud: When in history have rich women ever wanted to look like regular ones?

Kylie Jenner is widely considered the face that launched a thousand fillers. The reality star did her lips in 2014, and seemingly everything else soon after. If you believe social media, the model Bella Hadid covered Carla Bruni’s features like a singer does another’s song. Emily Ratajkowski, the extended Kardashian cast: Each began to modify herself until as if in some joint experiment they arrived at an aesthetic congruence. Their platonic ideal was an ethnically ambiguous woman, neotenous from the neck up, hypersexual from the neck down. Her whole schtick is that she looks unlikely to know who Plato is. That way when Emily, who is both a model and an essayist, seems likely to have read him, she gets not only your desire but also the delicious gotcha of having been misjudged.

Captured on Instagram grids, TikToks, and Snapchat stories, analyzed in duplicated miniature the world over, the gradual alterations of these famous faces became undeniable. And so, at least partially, they gave up denying them. Kylie confessed to her lips. Bella, much later, to her nose job. Filters, like “fox eyes” or “perfect nose,” permitted young women to try on, like hats, these features, just as it became increasingly normalized to go out and get them. Cosmetic surgeons advertised their noninvasive, or “reversible” work on viral videos. The changes harbored a new life. Women learned that, if they were beautiful, they could make ludicrous money just existing online. The price of Botox dropped by 27% over two decades, as the price of seemingly everything else went higher.

And then, like malware which self-replicates, the now-obvious face began to obviously spread, first among the brash reality contestants, the dubious streamers, DJs, ladder-climbers and professional plus-ones. Onto the influencers, even the wholesome ones, respected designers, singers and actors. On and on, until it found in the average millennial woman with disposable income an unexpected and fatal respectability. So demand for Botox increased tenfold over 20 years, skewing ever younger than before. So 16 million minimally invasive cosmetic procedures were performed in the U.S. in 2019, with 2018 seeing more than 7 million neurotoxin injections. And so it won’t stop until the faces in all our phones resemble not just each other but the one we see in the mirror.

Except that by approaching universality, Instagram Face actually secured its role as an instrument of class distinction—a mark of a certain kind of woman. The women who don’t mind looking like others, or the conspicuousness of the work they’ve had done. Those who think otherwise just haven’t spent enough time with them in real life. Instagram Face goes with implants, middle-aged dates and nails too long to pick up the check. Batting false eyelashes, there in the restaurant it orders for dinner all the food groups of nouveau riche Dubai: caviar, truffle, fillers, foie gras, Botox, bottle service, bodycon silhouettes. The look, in that restaurant and everywhere, has reached a definite status. It’s the girlfriend, not the wife.

Does cosmetic work have a particular class? It has a price tag, which can amount to the same thing, unless that price drops low enough. Or unless women of all classes are willing to pay it, no matter how apparently prohibitive the cost. Before the introduction of Botox and hyaluronic acid dermal fillers in 2002 and 2003, respectively, aesthetic work was serious, expensive. Nose jobs and face lifts required general anesthesia, not insignificant recovery time, and cost thousands of dollars (in 2000, a facelift was $5,416 on average, and a rhinoplasty $4,109, around $9,400 and $7,000 adjusted).

In contrast, the average price of a syringe of hyaluronic acid filler today is $684, while treating, for example, the forehead and eyes with Botox will put you out anywhere from $300 to $600. It’s been well-reported that during a single lunch break and without financial ruin, the contemporary professional can paralyze her masseters, fill in her undereye troughs, soften the bump on her nose, remove any indication of worry, effort, or time’s passage from her face. But Botox and filler only accelerated a trend that began in the ’70s and ’80s and is just now reaching its saturation point.

In 2018, use of Botox and fillers was up 18% and 20% from five years prior.

In 1978, The New York Times announced that aesthetic surgery was “no longer only for the rich.” They cited mothers returning to work, bank loans, tax deductions, years of savings and a philosophy of personal investment to explain the spread of procedures, up 5% to 10% a year, once reserved for “celebrities, jet setters and tycoons, or more precisely, wives of tycoons” to “the people who sit in front of the television set rather than appear on it.” In 1981, the American Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons revealed that 52% of recipients of plastic surgery had an annual income of less than $25,000 (around $80,000 today). In 1988, The New York Times reported on disastrous silicone injections and procedures which had become “commonplace for everyone from the C.E.O. to the rank-and-file union member, male as well as female.” In 2004, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons surveyed future patients, all considering procedures within the next two years: 30% of them had household incomes below $30,000 (today $47,000). In 2010, 71% of cosmetic surgery patients had average incomes. Between 1998 and 2018, cosmetic procedures’ average cost increased more slowly than inflation. Botox bars, and med spas, which promise speedier, more affordable treatments than doctors’ offices, have abounded. So have payment plans, BNPL financing, and gimmicks like provider credit cards with “interest-free” loans.

Accessibility went up, and so did demand; demand went up, and so did accessibility, or at least sheer force of will. Consider it the opposite of the luxury sector’s strategy, where Birkin bags maintained their chokehold not despite but because of an infamous exclusivity, sometimes in the form of a six-year wait. In 2018, use of Botox and fillers was up 18% and 20% from five years prior. Philosophies of prejuvenation have made Botox use jump 22% among 22- to 37-year-olds in half a decade as well. By 2030, global noninvasive aesthetic treatments are predicted to triple.

The trouble is that a status symbol, without status, is common.

Beauty has always been exclusive. When someone strikes you as pretty, it means they are something that everyone else is not. Oversize lips depend on undersize ones. Thick hair exists only in reference-distance of thin. It’s a zero-sum game, as relative as our morals. Naturally, we hoard of beauty what we can. It’s why we call grooming tips “secrets.”

Largely the secrets started with the wealthy, who possess the requisite money and leisure to spare on their appearances. Or they have belonged to women who, by virtue of their beauty, became rich, and in the grand tradition of the chicken or the egg, became only more beautiful still: actresses, models, royals, philanthropy-minded wives. Empress Sisi of Austria slept with slabs of raw veal on her face, wore imported corsets, brushed her hair for three hours a day. Jackie O. survived on a daily baked potato with sour cream and a spoonful of beluga caviar. Still-experimental electrolysis gave Rita Hayworth a whiter, higher hairline. Marlene Dietrich may very well have removed her molars. Marilyn Monroe, just maybe, did her nose. For quite some time, supermodels advised us to drink water, but surely, secretly, did a great deal more.

Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, but only because imitation was for most of history inexact. We copied the beautiful and the rich, not in facsimile, but in homage. Empress Josephine’s empire waist. Marie Antoinette’s cotton chemise. Clara Bow’s bob, Elizabeth Taylor’s bosom, Twiggy’s lashes, Cindy Crawford’s mouth: Appearances filtered down, achieving the mass reproduction we call a trend, but at such a slow pace and with such a resulting clarity of direction that its originator and her echoes could never be mistaken for one another. Simply because we didn’t have the tools for anything more than emulation. Fake breasts and overdrawn lips only approximated real ones; a birthmark drawn with pencil would always be just that.

Instagram Face, on the other hand, distinguishes itself by its sheer reproducibility. Not only because of those new cosmetic technologies, which can truly reshape features, at reasonable cost and with little risk. And not just because our smartphones have made trends instantaneously and widely visible, unlike films and magazine covers, which lagged. But also because built in to the whole premise of reversible, low-stakes modification is an indefinite flux, and thus a lack of discretion.

Gone is the “grand reveal” of a new beauty on the scene, freshly but clandestinely altered before her arrival, whose innovative appearance starts a frenzy. Instead we have a stream of before-and-afters of the same face, month after month, year after year, procedure after procedure, all in our pockets. These function as both an instruction manual and a sign of total defeat: There is simply no way to claim these changes are natural. Instagram Face has replicated outward, with trendsetters giving up competing with one another in favor of looking eerily alike. And obviously it has replicated down.

But the more rapidly it replicates, and the clearer our manuals for quick imitation become, the closer we get to singularity—that moment Kim Kardashian fears unlike any other: the moment when it becomes unclear whether we’re copying her, or whether she is copying us.

Which may be why she and other progenitors of Instagram Face—suddenly confronted with hordes of clones—have begun fighting a fierce war of plausible deniability. Kim, despite all visible evidence to the contrary, denies using filler and once, on television, X-rayed her butt, to demonstrate that it was bona fide. (It was not; from one day to the next last year, it actually vanished.) Though Bella Hadid copped to her nose job in 2022, that was 11 years and thousands of irrefutable memes after she did it. Kendall Jenner blames liner for her unrecognizable lips. Kylie tried that for some time, and now just pretends to have dissolved them. J-Lo, as she would, denies everything. On online forums, any mention of Selena Gomez’s rather obvious aesthetic work is attacked by loyal fans, blaming her genuinely unfortunate diagnosis of lupus and the steroids which yes, treat lupus, but do not, in any way, cause fox eyes. They’re defending something. It’s her character. But why?

Because, as these women know, natural looks have always been, and still are, more valuable than artificial ones. Partly because of our urge to legitimize in any way we can the advantages we have over other people. Hotness is a class struggle. The beauty of the princess justifies her estate. The symmetry of the wealthy, the sanity of the system. One is never insecure about one’s rightful place, and what could be more insecure than a nose job?

Indeed, a certain class of woman has managed to engage thoroughly in cosmetic work without falling victim to homogenization. Their relative security, financial and emotional, means they can afford what the Instagram Face sold off a long time ago. As more and more women post videos of themselves eating, sleeping, dressing, dancing, and Only-Fanning online, in a logical bid for economic ascendance, the women who haven’t needed to do that gain a new status symbol. Privacy. A life which is not a ticketed show. An intimacy that does not admit advertisers. A face that does not broadcast its insecurity, or the work undergone to correct it. It’s a marker of distinction that is, by definition, unmarked. Privacy separates women from men, who have trained us to respect, mystery, incuriosity. It also separates women from each other, in a schema old as time. The ones whose personal lives are for sale from the ones whose aren’t.

Upper class, private women get discrete work done. The differences aren’t in the procedures themselves—they’re the same—but in disposition. Eva, who lives between central London, Geneva, and the south of France, says: “I do stuff, but none of the stuff I do is at all in my head associated with Instagram Face. Essentially you do similar procedures, but the end goal is completely different. Because they are trying to get the result of looking like another human being, and I’m just beautifying myself.” Eva had lower-eyelid surgery at 20 years old to correct what she described as chronic puffiness; for the past few years, she uses filler in her upper lip and in her chin, to engineer symmetry. She is 28 but appears younger. Eva looks like Eva. If she has procedures in common with Kim K, you couldn’t tell. “I look at my features and I think long and hard of how I can, without looking different and while keeping as natural as possible, make them look better and more proportional. I’m against everything that is too invasive. My problem with Instagram Face is that if you want to look like someone else, you should be in therapy.” Finally, after listing her procedures, she concludes, “I changed my face without changing my face.”

‘The good work is going undetected,’ Dr. Wassim Taktouk told me recently. ‘The only stuff you see is bad work.’

Dr. Wassim J. Taktouk owns an aesthetic medical and laser dermatology clinic in Knightsbridge, London’s most expensive address. His clients are upper-crust, sometimes famous, and it’s not a coincidence that the clinic is described on its website as “discreet by design” and “tucked away in a residential corner.” Dr. Taktouk is celebrated for his subtle results and is in high demand. Would-be patients wait for an appointment sometimes for months. “The good work is going undetected,” he told me recently. “The only stuff you see is bad work.” Among the undetectable treatments Dr. Taktouk’s clinic offers are neuromodulators for crow’s feet, bunny lines, gummy smiles; thread lifts; dermal fillers at £595 a syringe for nonsurgical rhinoplasties, temples, ear lobes, tear troughs; injectable boosters; and a procedure bundle referred to as MesmerEyes. Sometimes a new patient comes in and has “lost sight,” as he calls it, so he’ll begin a “detox,” forge a “clean slate, dissolve it all and start again.”

What she’s lost sight of in those cases and what he restores is complicated and yet not complicated at all. It’s herself, the fingerprint of her features. Her aura, her presence and genealogy, her authenticity in space and time. The philosophy is that a face can withstand some changes but not too many, and only if they are made with particularity in mind. “We’ve been preaching that for a while. It’s what we try to teach. It’s not a one size fits all,” Dr. Taktouk says. The latter to him means a kind of “package.” “They give you widened cheeks, they make your nose narrower, they give you a heart-shaped face, they lengthen the chin, they make the lips plumper,” he explains. Dr. Taktouk’s approach is “not so formulaic.” He aims to give his patients the “better versions of themselves.” “It’s not about trying to be anyone else,” he says, “or creating a conveyor belt of patients. It’s about working with your best features, enhancing them, but still looking like you.” He praises new, smarter fillers,like Teoxane’s RHA, that stretch and move dynamically with the face, and avoid the lumpiness that he says, “gives the game away.” He never does.

Of good work, Dr. Taktouk says, finally: “You can’t see where it is, because it’s not so vulgar.” Vulgar. I’ve said it too without saying it. That word, for the Instagram Faced, might as well be the grim reaper (and what a hollow-cheeked resemblance after all). “Vulgar” says that in pursuing indistinguishability, women have been duped into another punishing divide. “Vulgar” says that the subtlety of his work is what signals its special class—and that the women who’ve obtained Instagram Face for mobility’s sake have unwittingly shut themselves out of it. It’s all fun and games for celebrities, but for regular women, what’s written on their faces now might as well be a target on their backs.

Which may be why doctors are now reporting growing numbers of women requesting injections of hyaluronidase, an enzyme which breaks down hyaluronic acid and permits it to be absorbed. From TikTok stars to reality show contestants, to the Kardashians’ not-so-subtly reversed BBLs, the tide is not so much turning as being dissolved. The hashtag #lipdissolving has 67 million views on TikTok, and none of the faces in the videos looks more than 40. Aesthetic laser treatments, which are not only surgically noninvasive but also aesthetically so, tightening the skin, improving the complexion, changing the face without changing it, are predicted to expand globally by 17% in the next seven years.

But what if, thanks to merciless biology, your features have already changed? What if, God forbid, you’re above 60? There’s nothing so exclusive as time. When Dr. Taktouk works with older patients, he asks them for photos from decades ago, and sees to what extent he can turn back the clock. It’s a process of restoration that can’t ever quite get there. While younger women are dissolving their gratuitous work, the 64-year-old Madonna appeared at the Grammy Awards in early February, looking so tragically unlike herself that the internet launched an immediate postmortem.

The tragedy was not the volume of her work, or even its obviousness, but that somehow, with every resource at her disposal, Madonna failed to get even close to the hopeless thing we wanted. Not the homogenized version of her that we saw, modeled after others, but the nostalgic one that doesn’t exist anymore. The young Madonna of the ‘80s and ‘90s. As if by seeing her again we, too, might reclaim our former selves. Our anger at her is our anger that we can’t do so. The folly of Instagram Face is that in pursuing a bionic ideal, it turns cosmetic technology away from not just the reality of class and power, but also the great, poignant, painful human project of trying to reverse time. It misses the point of what we find beautiful: that which is ephemeral, and can’t be reproduced. Our own particularities which, once decayed, can’t be brought to life again.

Age is just one of the hierarchies Instagram Face can’t topple, in the history of women striving versus the women already arrived. What exactly have they arrived at? Youth, temporarily. Wealth. Emotional security. Privacy. Personal choices, like cosmetic decisions, which are not so public, and do not have to be defended as empowered, in the defeatist humiliation of our times. Maybe they’ve arrived at love, which for women has never been separate from the things I’ve already mentioned.

On this, I can’t help but recall the time I was chatting with a plastic surgeon. I began to point to my features, my flaws. I asked her, “What would you do to me, if I were your patient?” I had many ideas. She gazed at me, and then noticed my ring. “Nothing,” she said. “You’re already married.”

Grazie Sophia Christie is a Miami-born writer living in London.