Are Conservatives the New Queers?

The medical fear and moral judgment that once surrounded HIV have reemerged in the contemptuous debate over how to manage COVID

Out of straight people’s earshot, my conversations with other gay men about COVID often alight on comparisons with HIV. We note the profiles on dating and sex apps by which men declare themselves vaccinated—often with the date and brand of the doses—and enthusiasm for bareback (condomless) intercourse. And we joke—although I, at least, mean it—about our relief to find ourselves in a public health crisis for which we cannot be held specifically responsible.

Of course, such talk is horribly tasteless. But there are strange parallels and stranger contrasts between the discourses by which Americans have tried to understand the two epidemics of COVID and HIV. Coming of age just as the latter began to fade from a terrifying crisis and shadow over gay sex into, for many gay men, a matter of relative unconcern that can be prevented with daily medication, it has been dizzyingly disorienting to see the type of medical fear and moral judgment that once attended HIV reactivated and reorganized around a new disease associated with very different victim-cum-villains.

Those unvaccinated for COVID, who include some of my friends and family members, figure, in everyday conversations and debates among self-consciously responsible observers from the left and center as targets of disgust and opprobrium, a disturbed subculture whose decimation by illness is both horrifying and deserved. On the right, meanwhile, resistance to COVID-era public health mandates at times takes on the lurid, perverse enjoyment of self-conscious transgression, the sort of dark pleasure in rule-breaking that seems incongruous among stolid advocates of family values and traditional morality. As gay men become less identified in the public mind with medical danger and moral decay, queerness, the status of belonging to a marginal and threatening periphery of the social order, ironically is becoming linked with the right.

We cannot think about personal and public catastrophes like epidemics without dramaturgy, giving a rhetorical and ethical charge to what, understood objectively, are natural phenomena that don’t care much about us or our behaviors. So Susan Sontag rightly noted in her essays Illness as Metaphor (1978) and AIDS and Its Metaphors (1987). Having said so, however, Sontag did “try to retire” certain styles of dramatizing illnesses. She objected with clarity and acrimony to the rhetorical sleights by which we imagine cancer, AIDS, and other maladies as expressions of individual ethical failings or as “enemies” to be confronted with military language. In her most optimistic moments, she hoped we might find a way of talking about disease without fable or moral—literally, neutrally, dispassionately.

Sontag’s attempt to “calm the imagination” showed her debts to Roland Barthes, the French intellectual whom she had introduced to the American mainstream in the 1970s. Barthes advocated, in this period, a pursuit of “the neutral” that would allow one to approach questions without the old, conflict-generating binaries of right and left, good and evil, etc. But he cautioned that such a strategy could elude conflicts, not overcome them. Sontag dreamed of a kind of hermeneutic practice that would “deprive something of meaning,” undoing previous interpretations of disease, laden with accusation and antagonism, in order to clear the air for a calmer, more reasonable way of talking. Scraped clean of encrusted meanings, a disease could be seen as it really is, “just a disease.” Barthes, in contrast, suggested that the way in which struggles between competing political and ethical projects threaten to subsume all aspects of our lives is not an accident to be undone by dispassionate analysis, but the general, permanent state of humanity—which artful forms of reinterpretation sometimes allow us temporarily to evade.

Sontag also had flashes of prescient pessimism in which she argued that, as a society, we cannot do without some feared and hated disease, and some feared and hated group especially associated with it: a metaphor-laden malady and a marginal community to blame. Looking back to the AIDS crisis may help us, if not to escape the imperative to dramatize and moralize illness, at least to gain some insight into the different modes of moralism—and to the strange ways these circulate across the political spectrum.

HIV and COVID, both epidemics, are not comparable illnesses. During the 1980s, HIV led almost inevitably to AIDS and death—a sentence that fell primarily on adults at the height of their vitality, who ought to have had many healthy years ahead of them. COVID, although it has killed many people, is far less fatal, particularly to the young and middle-aged. It is in no way to diminish the tragedy of the current epidemic that we must recognize its victims have been, for the most part, people who have already lived full lives, and who were, statistically, deprived on average of several months of life, rather than decades.

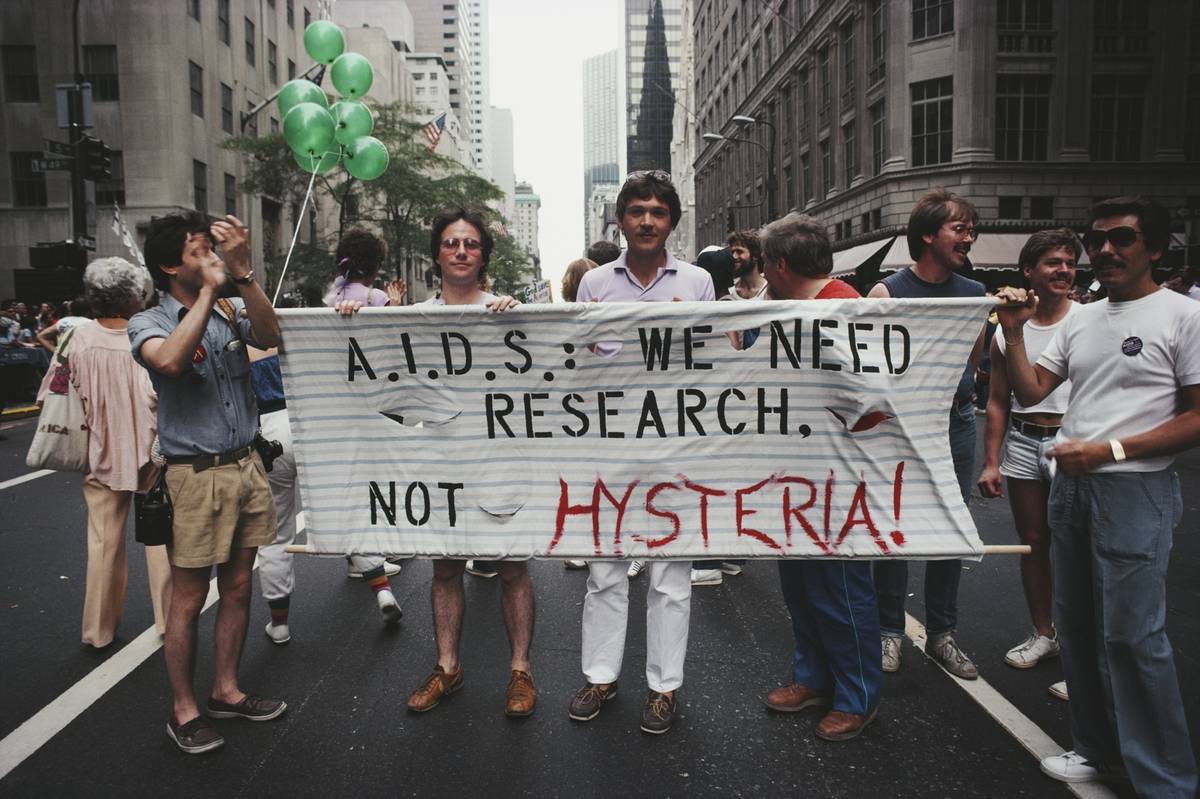

In their political effects, too, the diseases have been quite different. For years AIDS was ignored by the Reagan administration, which seemed content to let the populations most affected—gay men and intravenous drug users—die out of view, in parallel to the oblivion to which it consigned those whose communities were devastated by heroin and crack. COVID, from its inception, has been at the center of our political life, even if Trump’s maskless 2020 campaign rallies seemed, in what for the attendees seems to have been an ecstasy of collective effervescence, to suspend awareness of this reality.

COVID is not AIDS, no more than Biden or Trump are Reagan (although the three have in common, as presidents, a certain smilingly senescent distance from the suffering of ordinary citizens). But through both epidemics, we can trace a common set of rhetorical poses by which, as Sontag put it, individuals took the crisis as “an invitation to self-righteousness.” We all participate in the stupidest, rawest, and most obvious form of such moralism, which suffuses our private lives. Our holidays, for instance, are planned through charged conversations about who among the possible guests is or is not vaccinated. In every case some potential guest’s body not only might pose—to COVID-anxious or vaccine-wary relatives—the danger of contamination, but also an opportunity to whisper and judge how such-and-such a person has made an ethical mess of themselves, opening their body to foreign substances and their mind to the lies of Big Pharma or conservative media. Susceptibility to infection or influence appears as a moral failing, an inability to have sustained oneself as the right kind of subject.

In the imagination, both those skeptical of vaccines and of those who hold the former in obloquy, this proper sort of subject seems, through a careful management of their social ties and media consumption, to keep body and mind impervious to undesirable external forces. Falling ill, or into false belief, is a breach in the circuit of self-regulation, of critical thinking, or of deference to the correct authorities.

For all their disagreement, interlocutors seem certain that something essential about a person’s goodness or badness is revealed in the disclosure of such information as their vaccination status, most recent test, and eagerness to receive a booster shot. The moral person, who resists sickness and credulity, is also a member of one’s own side, ranged with oneself against those others whose poor choices and foolish ideas endanger our collective well-being. Questions of health, belief, morality, and identity appear inextricably bound together, as if it were impossible to imagine a person physically healthy but not morally good, or a person who believes “the right” things without being genuinely virtuous, or a person who is virtuous but not on “our side.” The good things in life go harmoniously together, we agree—or at least they would, were it not for the interference of grotesquely imbecilic enemies. This inescapable everyday moralism confuses our thinking, but helps us maintain our standing in our communities as solid, respectable individuals with a core of ethical agency through which we resist bodily weakness, misinformation, and the nefarious out-group.

Such quotidian, confidently doltish self-righteousness, sure that bad things happen to bad people (and that we are not among them) is the glue that helps hold society together; it is perhaps impervious to any critique except that which, from the heavens, God issued to Job. But there are more subtle, or perverse, forms of moralism, attractive particularly to intellectuals, that can perhaps be made to wither in the light. Two among them might be distinguished by their different relationships to abjection, abasement, and degradation. The first, a kind of sadism, delights in fantasies about the misery of those who suffer from a disease, while disguising its prurience as concern for their welfare. The second, a kind of masochism, turns the fantasy around, transforming abjection into liberation. While the sadist hides the pleasures of punishing beneath a hypocritical moral exterior, the masochist hides a will to power beneath the pose of amoral hedonism.

William F. Buckley, the Catholic conservative pundit who for decades led the American right from the desk of the National Review, offered a paradigmatic example of moralized sadism in a 1986 op-ed on the HIV crisis. Printed in The New York Times with the title, “Crucial Steps in Combatting the AIDS Epidemic,” the piece called for “universal testing” of all Americans for the virus. The various public and private institutions through which individuals might conceivably be enrolled for medical screening, such as hospitals, schools, and the military, should coordinate to identify those stricken with HIV. The latter would then be rounded up and tattooed on their arms and buttocks. These measures were preliminaries, aimed at the “private protection” of individuals who could check the status of potential sexual partners or fellow intravenous drug-users—but, Buckley warned, should they prove inadequate, more public forms of identifying the HIV-positive might be in order.

Although he acknowledged that people like himself, concerned to “protect the public,” who might be amenable to such views, “disapprove forcefully of homosexuality,” with which he unhesitatingly conflated with HIV, Buckley insisted that he approached the matter of public health “empirically.” He happened to find homosexuals abhorrent, but that had nothing to do with his proposals to brand the HIV-positive. This was no Scarlet Letter, he urged, but rather a morally neutral, scientifically valid means of preventing the transmission of disease. With President Reagan—as Alvin Felzenberg reports in his biography of Buckley, A Man and his Presidents—Buckley took a different tone, joking that the buttocks of the HIV-positive should bear the Dantesque inscription, “abandon hope, all ye who enter here.”

Buckley’s spirit, in the era of COVID, appears on the left and center rather than the right. Conservatives now largely oppose novel deployments of state power in the name of public health—now that they experience themselves as the targets rather than the masters of that power. It is from their opponents that we hear Buckley’s sort of ghastly jokes about the fates that the unvaccinated should meet. There is at times in conversations among observers from the left and center about the problem of COVID in America, alongside panic or despair about the number of past and future cases, a kind of barely unacknowledged enjoyment that the disease chiefly strikes those that moderates and progressives might imagine deserve it.

Just as supercilious cruelty, armed with the authority of science and wielded against the already-hated victims of a new disease, now animates the left rather the right, so has the right adopted a posture of antinomian transgression once associated in the discourse on HIV with the fringes of the academic and activist left. One of the most notorious documents in the latter is the 2009 book Unlimited Intimacy by Tim Dean, a professor of English at the University of Illinois. In it, Dean defends—indeed almost divinizes—unprotected anal sex between men and the subculture of “barebacking” that surrounded it. In that era, before the marketing of drugs for the prevention of the transmission of HIV made such practices, in the eyes of many gay men today, seem banal, Dean’s argument struck many—a college-age me among them—as a shocking breach of the consensus about safe sex that had developed in the late ’80s. Dean drew on thinkers like Michel Foucault to question the supposedly oppressive imperative to health that had become the center of a new Western morality supposedly centered around practices of self-management to increase productivity. In an especially troubling passage, he invoked Foucault’s own death from AIDS to argue that HIV could be a source of “pride” instead of “stigma and shame,” as HIV-positive gays could imagine themselves connected to each other through genealogies of disease transmission: “What would it mean for a young gay man today to be able to trace his virus back to, say, Michel Foucault?”

This valorization of unsafe sex, and even of the transmission of HIV, plays on two registers. On the one, Dean seeks to generate a great shudder of transgressive pleasure, breaking the most basic of taboos, indeed the most basic of values, that of life over death, to demonstrate his intellectual daring and freedom. The move, it must be acknowledged, is not one that is without precedent in Foucault’s own work, in which he insisted on the intimate connection between freedom and the willingness to risk death. At the same time, Dean insists on a countermorality, in which community (of the HIV-positive, or those willing to risk becoming so) becomes more valuable than individual health, or in which well-being is defined as identification with and participation in a chosen group rather than according to biological criteria.

In this sense that conservatives, amid the COVID crisis, are Foucault’s heirs rather than Buckley’s. In their resistance to mask mandates and vaccines, and flouting of public health protocols, conservatives appealed to ideas that weirdly mirrored the most outrageous derivations of French theory. Calling for churches and synagogues to stay open last year, they insisted on the importance of chosen ties, even biologically risky ones, against scientific protocols that imagined the good life only in terms of bodily health. Like Dean, conservatives often couch their resistance in two inconsistent registers, appealing both to the pleasure of rule-breaking—casting COVID-fearful officials and neighbors as joyless busybodies—and to the call of a higher rule, one from the vantage of which disease transmission is a trivial concern. Conservatives, no longer reigning from the commanding heights of our moral economy, and increasingly held in open contempt throughout the mainstream of elite opinion, try, incoherently, to present themselves as liberty-loving, libidinal dissidents, and as the bearers of a superior, more communitarian morality. In doing so, quite without knowing it, they merely reenact the poses of yesterday’s queer theory.

Sontag’s analysis of the metaphors by which we dramatize and moralize illness did not free us from them; neither can the present or any other essay durably sever us from the errors of the past and release us into a new freedom from misinterpretation. We might, however, by considering the continuities between the discourses on HIV and COVID, and the way in which the left and right seem to have swapped their preferred modes of transforming public health crises into opportunities to bully their enemies and aggrandize themselves, see our rhetorical weapons in a new light, imagining how they might be turned against us. Imagining this, we might wield them somewhat less ruthlessly and stupidly. Partisanship and moralism may be as inevitable as sickness, but perhaps we can at least remember, by looking to the past, that we and our supposed enemies, continually exchanging a limited number of tactics and identities, resemble nothing so much as each other.

Blake Smith, a contributing writer at Tablet, lives in Chicago.