Convivencia

A plaintive Gypsy song, possibly of Ladino origin, is hybridized and reinterpreted, then viewed on the Internet, where roots and homelands blur

The song “Naci en Alamo” (“I Was Born in Alamo”) is a soulful and stirring lament of Gypsies living in Europe today. It’s a song about displacement and homelessness and ultimately about nostalgia for a birthplace that was never home. There is no home, there is no homeland, there is no place of origin.

No tengo lugar

Y no tengo paisaje

Yo menos tengo patria

Naci en Alamo

I have no place

And I have no landscape

Still less do I have a homeland

I was born in Alamo

Like the history of the Gypsies, the song itself has become an archaeological enigma. It has crossed so many borders and been sung in so many languages that it is no longer easy to determine its roots or which precise Alamo, in either Spain or Portugal, the song is about. Even now, Naci en Alamo roams a pathless Odyssey around the Mediterranean, no less homeless than a Gypsy. The word “Gypsy” itself turns out to be a conundrum as well. Gypsies, who speak Romany, refer to themselves as Roma, not with the exonym Gypsy. (Roma is the plural for Rom, meaning “man”—no relation to Romania.) “Gypsy” in English, just like the word gyftos in Greek, may be derived from gipcya, with a possible derivation from egipcien, becauseGypsies were mysteriously believed to come from Egypt—which also means from far away, from elsewhere, or just simply from goodness-knows-where. Etymological dictionaries also suggest that the word might derive from the Greek for untouchables, athinganoi, hence zingaro in Italian, tsigane and gitan in French, gitano in Spanish, ţigan in Romanian, cigano in Portuguese. The real origin of the word, like the real origin of the people, is lost in time. There is no origin.

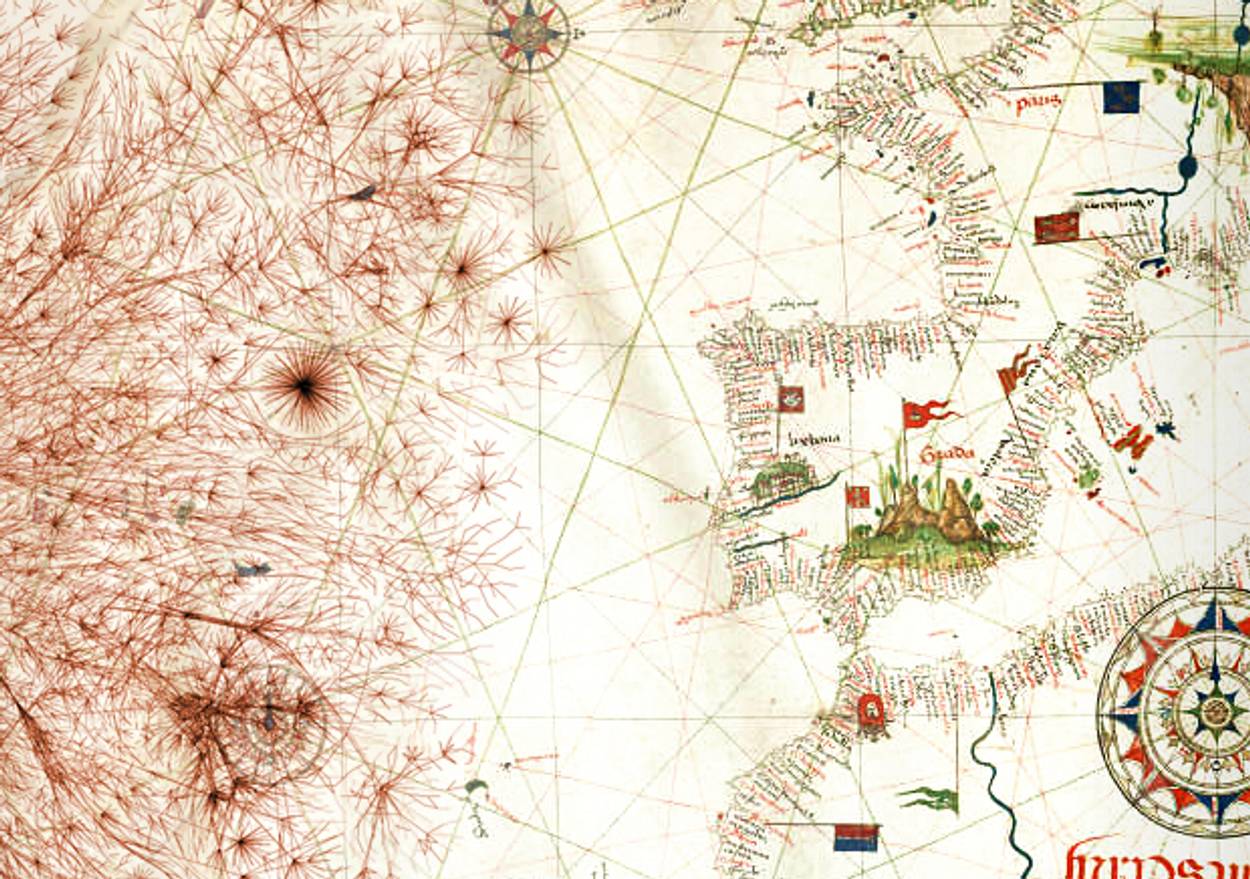

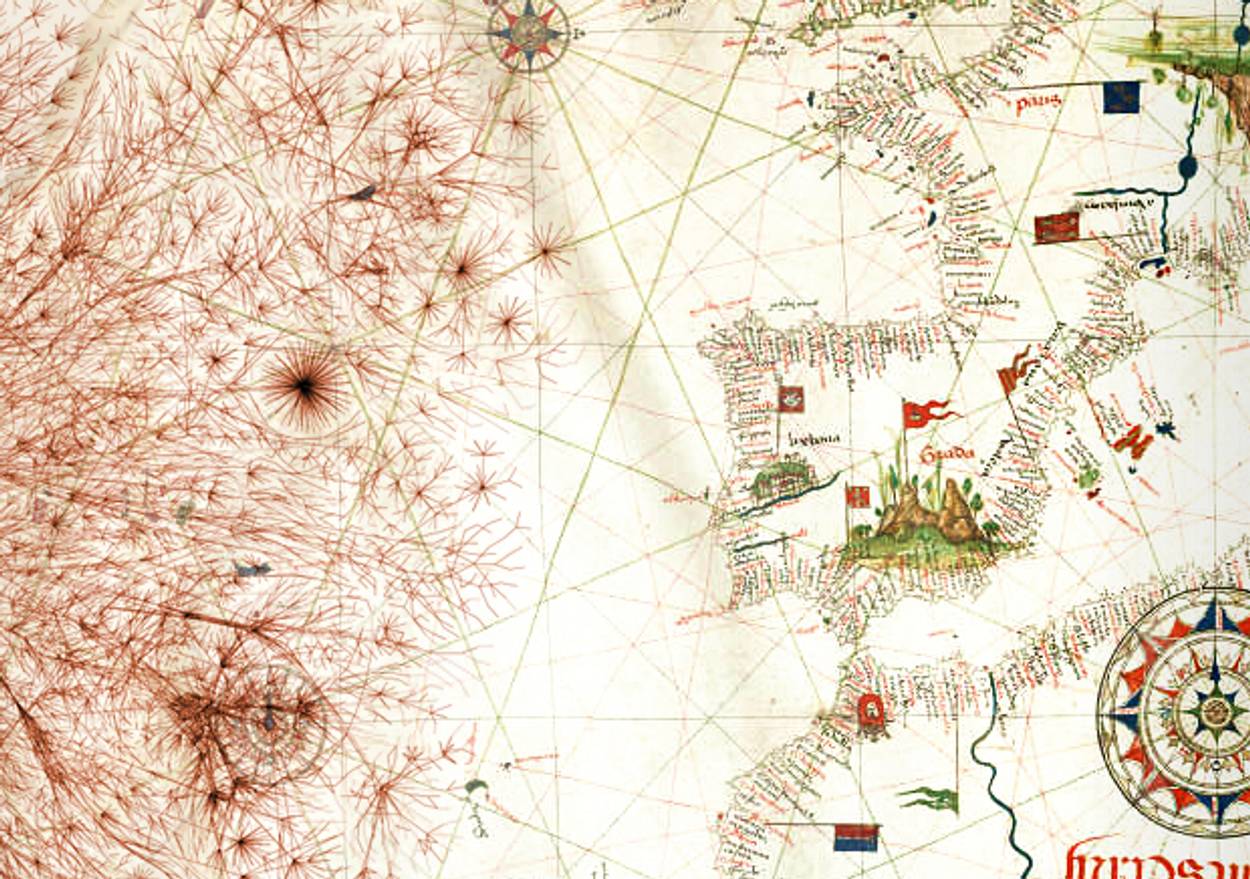

Western Europe first encountered “Naci en Alamo” in Tony Gatlif’s 2000 film Vengo. A stark, frequently violent, elegiac portrait of the hardscrabble lives of Gypsies, Vengo is rife with crime, drink, blood feuds, and, as always, music, laughter, and dance. The film opens with a gathering of a seemingly privileged audience in Spain about to enter a large ruined church temporarily converted into a concert hall. The camera focuses on a flamenco guitarist and a violinist and on the rhythmic loud clapping of hands. Soon enough, the camera shifts to another part of the hall where a group of Arab performers have joined the Spanish duo: drummers, a flautist, a violinist, and a lutanist, and finally a Flamenco Sufi singer, the Egyptian Ahmad Al Tuni, begins to chant to the rhythmic clank of a metal object, possibly a large key, which he strikes against a thick drinking glass—not an atypical percussive feature in flamenco folksongs, especially in the cante jondo (deep song) style. The blending of Arab with Andalusian strains, underscored by flamenco, with its Gypsy roots, is not new to Spain and harks back to the long period of Convivencia when Jews, Muslims, and Christians lived together in relative harmony there in the early Middle Ages. Some claim that cante jondo predates the Moorish invasion in the 8th century and goes back to Byzantine liturgical music. Even if this were true, it takes no expert to recognize that the more stirring and heartrending the sustained wail of cante jondo the clearer its affiliation to traditional Arab music.

It is no accident that Tony Gatlif should want to open his film with this scene. Not only is Gatlif restoring the millenary contributions of so many ethnicities in the creation of Spanish music, but, as with almost everything he touches, he is forever prodding questions of displacement, exile, memory, and cultural miscegenation. Things are never one thing; they are always hybrid. People don’t come from one place; they come from at least two. Gatlif is not just a Gypsy; he is an Algerian of Gypsy descent now living in France—displaced, that is, to the third degree. His name is not even Tony Gatlif; it is Michel Dahmani. Like the song, he too is without place, without homeland, without borders.

But then even the title of “Naci en Alamo” begins to shadow over. Alamo (not the Alamo in Texas) is a very small town in Portugal. The Internet, where hunches run amok and facts are distorted no differently than among early historians, suggests that several scenes of the film were indeed shot on location in or near Alamo. Alamo—and one could see why it drew the attention of a Gypsy filmmaker making a film about Gypsies—sits right on the very border between Portugal and Spain. It lies in no one country.

To further confuse matters, there is more than one Alamo in Portugal, just as there are several Alamos in Spain. In fact, there is an Alamo close to the one on the border just across from the Alamo near Seville.

Things get more complicated yet. “Naci en Alamo” sounds like “Naci en el amor”: “I was born of love, of passion,” but it could just as easily mean “out of wedlock.” Once again, the Internet and Gatlif favor Alamo over el amor, but the partisans of each staunchly stick to their views. Adjudication is pointless where speculation prevails or where rumor has the last word.

The matter becomes murkier yet when we learn that the original version of the song was not sung in Spanish at all but, as the film credits show, in Greek. It was composed around 1992 by Dionysis Tsakni. (But even this is not certain. Some sources allege an earlier date of composition, in 1986, for a Greek TV serial, To Bourini.) The song is officially titled “To tragoudi ton gyfton,” or “Song of the Gypsies,” but is mostly known by its refrain, nais balamo, which sounds uncannily similar to the refrain of the Spanish version, “Naci en Alamo.” Nais Balamo (also pronounced “nash balamo”) has been sung by numberless Greek singers and is an extremely popular hit in a country that, like so many countries in Europe, seldom looks favorably on its Gypsy population. Balamo means non-Gypsy, outsider, stranger. “Nais Balamo” means, “Go away, stranger.”

Here are the lyrics in Greek:

Δεν έχω τόπο, δεν έχω ελπίδα,

δε θα με χάσει καμιά πατρίδα

και με τα χέρια μου και την καρδιά μου

φτιάχνω τσαντίρια στα όνειρά μου

Νάις μπαλαμό, νάις μπαλαμό

Den exo topo, den exo elpida

de tha me hasi, kamia patrida

ke me ta heria mou ke tin kardia mou

ftiachno tsantiria sta onira mou

Nais balamos, nais balamos

I don’t have a place, I don’t have any hope

no homeland will ever lose me

and with my hands and with my heart

I put up tents in my dreams

Go away, stranger, go away, stranger.

The most celebrated version of this song in Greece is sung by the Greek singer Eleni Vitali. But ask any Greek, and he will unavoidably stumble over some of the lyrics, for these are composed in a macedoine of Greek and Romany, which suggests that the song might have originally been sung in Romany and only later inspired a loosely translated version in Greek, which retained some vestigial words form the original—if an ur-version other than the Greek ever existed. A similar case applies to an even more popular Mediterranean song, “Mustapha,”dating back to the early 1960s and composed in a polyglot medley of Arabic, French, and Italian. “Mustapha” has always been altered to suit the place and humor of its immediate audience, from France and Italy to Turkey, all the way around to Lebanon, Egypt, and Morocco. There is no origin—only speculation—just as there is no consensus about the origins of Bob Azzam, the man who made the song world famous. On the Internet, some say he was a Lebanese Christian singer born in Egypt, others that he was an Egyptian Jew, others still that he was a Palestinian Greek Orthodox.

***

More recently, “Naci en Alamo” was taken up by Israeli singer Yasmin Levy. Hers remains until today the most popular of all versions. But what is of particular interest is not so much the song itself (which she sings with great pathos in an Andalusian style that recalls in many ways the flamenco style), but the educated (and not so educated) response to her song. Once again, YouTube pullulates with conjecture. Because Levy sings the song in Spanish, and because her father was a Sephardic Jew who was born in Turkey and who settled in Israel, where he devoted years of his life to the collection and preservation of the Judeo-Hispanic songs of Sephardic Jews, would it not make sense to ask, some say, whether “Naci en Alamo” is not a Ladino song? Ladino is the language of the Sephardic Jews who were expelled from Spain in 1492 and settled in Holland, Greece, Turkey, and the Dalmatian coast and who, until today, continue to speak a language quite similar to modern Spanish. This would make some sense if one recalls that Jewish, Moorish, and Gypsy culture and music were profoundly interfused during the Concivencia. Conversos—Jews who converted to Catholicism to avoid persecution or deportation from the Iberian Peninsula—were frequently mistaken for Gypsies, and many sometimes claimed an obscure lineage, hoping to conceal their Jewish identity. The picaro, the most notable rogue/operator/jack-of-all-trades figure of Spanish literature, who was not averse to larceny and deceit and who is a product of the Converso imagination of writers like Francisco de Quevedo (1580-1645) and Mateo Alemán (1547–1615?), is himself frequently either of totally obscure or intentionally undisclosed origins if not illegitimate by birth. He appears on the scene and as suddenly disappears, like Charlie Chaplin—who had both alleged Jewish and Gypsy roots. The opera composer and singer Manuel García (1775–1832), the father of Maria Malibran (1808-1836), Europe’s most celebrated 19th-century mezzo-soprano, who was Pauline Viardot’s sister (1821–1910), also an opera singer, and Ivan Turgenev’s life-long love, was himself reputed to have been either a Gypsy or a Converso. When he landed in New York, García washelped by none other than Lorenzo da Ponte, the librettist of Mozart’s Don Giovanni, Così Fan Tutte, and The Marriage of Figaro, and did indeed sing in the first U.S. production of Don Giovanni with his son and his elder daughter.Da Ponte is known to have converted from Judaism to Catholicism and had been a good friend of Giacomo Casanova, a man who in his memoirs makes no secret of his Spanish origins.

***

All this, however, is idle speculation, because “Naci en Alamo” was composed in, or translated into, Greek somewhere between 1986 and 1992. One should ask Dionysis Tsakni for the song’s real origin. But as should be clear by now, the source is immaterial, for the song has, to use a cliché, acquired a life of its own and wanders from country to country, reflecting not the wishes of its author or authors but those of its listeners. What is not idle speculation, though, is how the song has always transcended all manner of boundaries and indeed invites boundary crossing and musical métissage. Eleni Vitali, the Greek singer who may, after all, have a Converso family surname, has sung it most recently with Haig Yazdjian, who lives in Greece but sings the words in Arabic and is himself an Armenian born in Syria, and therefore, like the film director Gatlif, a man displaced to the third degree. The combination of Vitali and Yazdjian is simply an eloquent instance of the compulsive hybridization and erasure of origins that the song invites. Vitali and Levy, incidentally, have sung together “Porque,” a song protesting violence in the name of God.

“Naci en Alamo” is also sung both in Spanish and in Arabic by the Tunisian singer Amel Mathlouthi. The song, titled “Naci en Palestina” (“I Was Born in Palestine”), speaks to the homelessness of Palestinians. There is, however, also an Israeli version by Haim Moshe, as there is one by Sofi Marinova in Bulgarian and one by Yonca Lodi in Turkish. Neither the Israeli, nor the Bulgarian, nor the Turkish say anything about gypsies, but sorrow underscores every word.

The moral here couldn’t be simpler. Arabs sing it, Jews sing it. Turks sing it and Greeks sing it. Without knowing it, perhaps maybe singers have figured out the secret of Convivencia long before historians and politicians. Which takes us back to the friendly concert hall at the beginning of Gatlif’s film Vengo. It hosts singers and performers from totally different parts of the world yet houses them in one room, one place, under one roof, and ultimately in one homeland to which all belonged once upon a time and still long to go back to as one longs to return to roots that may no longer exist or may never have existed at all except in the shadows of our collective memory. Everyone belongs elsewhere in the end, and elsewhere could mean both everywhere and nowhere.

Andre Aciman is a professor of comparative literature at the CUNY Graduate Center and is The New York Times bestselling author of Call Me by Your Name, Find Me, and Out of Egypt: A Memoir.