Jewish Self-Government in Europe Was Not Just a Dream—It Was a Failure

The Council of Four Lands was the central body of Jewish autonomy in Poland for nearly two centuries. What went wrong?

The Council of Four Lands (Va’ad Arba Aratzot) was the most elaborate and highly developed institutional structure in European Jewish history—a national council or parliament that existed from the mid-16th century to the 18th and whose decisions affected the lives of hundreds of thousands of Jews and sought to coordinate the policies and actions of hundreds of communities in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Born in the last quarter of the 16th century out of congresses of religious leaders and elders during great fairs in civic centers such as Lublin, the central institution emerged to serve local groups as supreme legislative, administrative, and—sometimes—judicial body.

In the absence of Jewish sovereignty anywhere in the world, the Council of Four Lands (usually connoting as well the Council of Lithuania with which it often worked in concert) served both as a reminder of Jewish sovereignty in the past and as a harbinger of the promised messianic Jewish state of the future. As the wine merchant and memoirist Ber of Bolechow, an 18th-century Polish Jew, noted: “This [Council] was for the Children of Israel a measure of Redemption and a bit of honor.”

Communication between the Va’ad (council) and Jewish communities outside of Poland was not standard or even commonplace, so its decisions and actions became known abroad only serendipitously. The very fact of its existence, however, aroused feelings of admiration. Rabbi Avraham Halevi, who lived in Egypt in the early 18th century asserted: “Poland is a great city of God and every pronouncement made there is spread to all the cities of Ashkenaz.” The Sephardi rabbis of Amsterdam wrote to the Va’ad, in 1671, addressing their letter to those whose “fortress [=authority] extends over the entire community of the Exile.”

It is noteworthy that these foreign observers spoke as if the Va’ad were a rabbinic body, or at least one led or dominated by rabbis. The sources make it clear, however, that the Va’ad’s members and leaders were mostly laymen and its authority did not derive from rabbinic sanction. For most of its existence, even rabbis who did sit on the Va’ad did so as representatives of their communities and not by virtue of their rabbinic office or training. Recent scholarship may have created an optical illusion that might make it easy for determined secularists, anti-Zionists, and modern-day Haredim alike to anachronistically imagine the Council of the Four Lands as a quasi-democratic body that functioned on European soil without instruments of coercion and without the bothersome trappings of a state—an alternate model for Jewish autonomy, outside the Middle East.

***

What was the nature and extent of the Va’ad’s authority outside of Poland? When and how was it employed? As the central governing body of the Jewish communities of Poland, the Va’ad filled a wide number of functions: enacting administrative, economic, religious, and social legislation; tax apportionment; supervising local communities in areas such as finance, education, and charity; regulating inter-communal relations; representing Polish Jewry to the agencies of the Polish government; and allocating resources and lending aid in emergency situations, such as in the wake of the Gezeirot (persecutions) of 1648-49. But the Va’ad’s relationship to other Jewish communities was neither defined nor regularized.

Observers thought that the Va’ad’s enactments in Poland were both widely known and widely accepted as binding decisions, at least by most Ashkenazi communities. Similarly, some modern scholars have claimed that the Va’ad exercised binding authority outside of Poland, in Ashkenaz (the German states, eastern France, the Low Countries), Italy, Bohemia, and Moravia. However, the Va’ad did not exercise power over other Jewish communities; it did enjoy influence beyond the borders of Poland. There was no legal authority; but there was moral authority.

One possible way to analyze the Va’ad’s moral authority outside of Poland is to consider the features of the various cases of Va’ad intervention in the internal affairs of non-Polish communities. In the 16th and early 17th centuries the leadership of the Jewish community of Frankfurt am Main was in the hands of a small group called Havruta Kadisha (the holy fellowship) or simply Havruta or Zehender (“the 10”). This was an oligarchical body that served as the council of the community, choosing two gabbaim (wardens) who administered communal affairs. Members of the Zehender were elected for life, and when it was necessary to choose a successor the only electors were the other members of the Havruta. In the period 1616-1628 there was a struggle between the Zehender and members of other groups in the community who opposed their rule and sought to broaden the membership of the communal council.

The Jews of Frankfurt had suffered a pogrom during the 1613-14 Fettmilch Rebellion and fled the city in August 1614. They returned, their safety guaranteed by the Habsburg Emperor Matthias, in February 1616. Soon thereafter the conflict over the leadership in the newly re-established community broke out when the opposition to the Zehender appealed to Matthias to break their monopoly, and the emperor assigned the problem to the same commissioners who were investigating the Fettmilch Rebellion. The Havruta presented the commissioners with a letter of acquiescence, signed by many supporters, affirming its ruling status. The imperial privilege granted to the Jewish community of Frankfurt (composed March 1616, officially confirmed January 1617) formally and finally recognized the Zehender as the community’s ruling body.

The opposition to the Zehender did not, however, die down. In the next round the parties agreed to submit the dispute to the arbitration of three prominent Ashkenazi rabbis. On Jan. 4, 1618, these arbitrators came to a compromise solution creating a new body, the Zayin Tuvei Ha-Ir (lit.: the seven good men of the city; i.e., communal elders), whose members, unlike the Zehender, could not be related to each other, were limited to a two-year term and at least four of whom could not be serving a consecutive term. The Zayin Tuvei Ha-Ir joined with the Zehender thus effectively expanding the communal council from 10 to 17, seven of whom came from outside the elite Havruta. Unfortunately, this solution did not work. The opponents of the Zehender soon complained that the oligarchs, who still constituted the majority on the council, refused to keep proper financial records, perverted justice in judicial matters, persisted in their nepotism, and failed to invite members of the Zayin Tuvei Ha-Ir to council meetings.

The Zehender offered to limit the number of close relatives who could serve together on the council, but this proposal was rejected by their opponents as a half-measure. The herem (ban) that the Havruta placed on one Hirsch zur gelben Rose in 1621 was the opening volley in the next stage of the struggle. Hirsch, supported by several other householders, appealed the ban and protested against the generally despotic behavior of the Zehender to the Emperor Ferdinand II in Vienna. The emperor ordered the Frankfurt City Council to investigate and come up with a resolution acceptable to both sides. In February 1622, after a lengthy inquiry, the City Council decided to abolish both the Zehender and the Zayin Tuvei Ha-Ir and to establish in their place a new institution, which would include 14 members: six from the old Havruta and eight who would be appointed by the Frankfurt municipal authorities from among 16 candidates to be chosen by the Jewish community.

This arrangement entailed a significant loss of Jewish autonomy, for everywhere in the empire Jewish communities had the right to choose their own leadership. The effect of this forced concession was to augment unrest in the Jewish community; one (unidentified) faction decided to send an emissary to the Va’ad in Poland (at the time called the Council of Three Lands). A draft of the document that defined the purposes and conditions of this mission and indicated what the petitioners expected from the Va’ad has recently been published and is worth examining closely:

The Three Lands, may God keep them, should declare a great Herem (ban) on the elders of the Frankfurt community specifying that they not meet together or come into contact with each other … and that they on no account be called by the name “elders” (parnassim). And [the Va’ad] should immediately intercede with our exalted ruler so that elders be chosen by the community and not by the ruler in any way. They should also intercede on behalf of the Jewish court system that disputes not come up before the Gentile courts ever. All of these [measures] are to be accompanied by a strict sanction, an edict of naha”sh, that if [the elders] refuse and do not obey these [measures] then the communities of Ashkenaz, their rabbis and elders, are obligated to ban the recalcitrant elders [of Frankfurt] and all who support them … and if the communities of Ashkenaz refuse to ban the recalcitrant elders of Frankfurt, then this document does not take effect until the Three Lands ban both the communities of Ashkenaz and the elders of Frankfurt, individually, each by name. … Furthermore I [the emissary] will advocate [that the Va’ad] ban any cantor or bailiff who summons the elders of Frankfurt to convene together. They should also ban anyone who receives from [the banned elders] any appointment, whether as bailiff or judge or [warden of] the community trust or charity warden or rabbi. They should also ban anyone who marries with them as well as the rabbi who performs the ceremony. I will also advocate that the Three Lands censure the elders of Frankfurt in all of the communities if [these elders] refuse and do not obey their teachers.

At least three letters were sent to Frankfurt demanding the abolition of the council appointed by the municipality and the institution of a method of choosing the Jewish leadership acceptable to the Jews. The Va’ad understood, however, that its standing in this matter and its right to intervene were not at all clear:

For until now we kept our head inside, not venturing beyond our territory and God forbid that we or our progeny lord it over you. God forbid. This is not our way. … What will you accept from us if, God forbid, you judge us guilty and castigate our words? What would it be all about and what would we gain, [you] becoming enraged over our interfering in your dispute which is “not ours, O Lord, not ours”(Ps.115) [i.e., is none of our business] …

The Va’ad took pains to explain that it did not see the leadership of the Frankfurt community as its subordinate but rather as its equal. As peers, the two bodies were entitled to reprove each other:

There has always been an eternal covenant between us and you, between our fathers and yours. … Were your words of some exoteric reproach but esoteric love, alerting us to the truth and a perversion of justice, to reach us we would take it as praise and honor.

This approach laid the foundation for the intervention of the Va’ad in the process of choosing the Frankfurt leadership. The Va’ad did not claim the right to exercise authority over Frankfurt. It did not even flaunt its prestige as entitling it, as Rabbi Halevi had asserted, to obedience on the part of other communities. The Va’ad’s claim was more modest and generic:

But in any case, we will do our duty in line with [the command]: “Reprove [your neighbor]” (Lev. 19:17) even [if it takes] several times (Sefer Ha-Hinukh, no. 239), because “it is time to act for the Lord” (Ps. 119:126) and where God’s name is being desecrated you don’t stand on ceremony (Midrash Tanhuma, Mishpatim 6).

By offering this justification, the Va’ad was basing its right to express an opinion in the Frankfurt affair on the obligation of every Jew to protest transgression whenever he witnessed it. The Va’ad had no special standing: It was intervening as a peer group interested in defending the Torah.

Despite the request of the faction that had sent the emissary to Poland, the Va’ad did not intend to mediate between the rival factions of the Frankfurt community, nor to pacify the community that had been plagued by infighting for some 10 years. While it was the Frankfurt emissary who drew the Va’ad’s attention to the conflict in Frankfurt, the Va’ad itself gave as the reason for its intervention that the Frankfurt affair had set a dangerous precedent. It represented a deviation from the virtually universal Jewish custom of choosing their own leaders and was a blow to the foundations of Jewish existence as a minority in Europe

As the framers of the emissary’s charge wanted, the Va’ad did indeed disqualify the elders of Frankfurt, ordering the people of the community not to recognize them. In order to reinforce its ruling the Va’ad threatened to impose sanctions on the elders of Frankfurt if they did not accept the Va’ad’s decision. The sanctions included a great Herem; notification of the ban to the sages of Prague, Eretz Israel, and other communities; publication of the names of the recalcitrants throughout Poland and other places as well; punishing Frankfurt Jews who happened to be visiting Polish communities; and unspecified legal measures.

So, what was the outcome of the intervention of the Va’ad in the affairs of Frankfurt? Firstly, it seems that the Va’ad itself had doubts as to the validity of its ruling in a community that was not under its legal jurisdiction. Therefore it warned,

Let not your evil inclination seduce you to say about us: “They are far from us and we have no link to any of them. What is there between us in common?”

The Va’ad’s doubts as to the readiness of the Frankfurt community to respect its orders were well-founded. The first letter sent by the Va’ad to Frankfurt was ripped up by its recipients. As the Va’ad’s men put it in their second missive, “Our words are contemptuous and disgusting in your eyes. … You mocked our words.” The conflict in Frankfurt was finally resolved by means of compromise between the factions: Rabbi Haim bar Yitzhak Cohen of Prague, the grandson of the famous Rabbi Judah Loew, was appointed as Frankfurt’s rabbi in 1627, and the compromise agreement actually included an explicit rejection of the Polish Va’ad’s intervention.

***

From 1660 there were two Ashkenazi communities in Amsterdam: the “Ashkenazi,” founded in 1635; and the “Polish,” made up of refugees from the Muscovite Invasion of Poland-Lithuania in 1654-55 who followed the customs of Lithuanian Jewry. The larger and better-established Ashkenazi community seems to have acquiesced in the founding of the Polish community, but conflict soon developed and the Ashkenazi community apparently tried to force the Polish community to merge with it. In reaction, the Polish Jews evidently turned to the Va’ad for support.

The Va’ad sent a letter to Amsterdam asking the Sephardim to come to “the aid of the Polish congregation, may God protect them.” Their help took the form of interceding with the authorities on behalf of the Poles. The Va’ad declared the Sephardi elders should be the arbitrators between the Poles and the Ashkenazim. The Ashkenazim continued attacking the independence of the Poles and also cast aspersions on the ability of the Sephardim to serve as an authority in these affairs. Around 1671 the Va’ad withdrew its endorsement of arbitration by the Sephardim and came out in favor of the amalgamation of the two communities. The dispute ended in late 1672 or early 1673 when the Polish community protested to the Amsterdam municipal authorities against the refusal of the Ashkenazi community to split the revenue from the Ashkenazi slaughterhouse. The municipality appointed a commission of inquiry, and on July 26, 1673, after the commission concluded its investigation, the municipality prohibited the Polish community from gathering separately and “permitted” it to merge with the Ashkenazi community.

Our main sources for this episode are two letters sent to the Va’ad by representatives of the Sephardi community protesting the Va’ad’s change of heart. The tone of these letters implies that all parties involved related to the Va’ad’s decisions with respect: the Poles who sought support; the Ashkenazim who tried to change the policy of the Va’ad; and the Sephardim who were angered by the change. That said, however, there still is no evidence that the Va’ad’s word decided the issue. The uniting of the two communities resulted from the order of the municipal authorities in the wake of the Poles’ appeal and not because of the parties’ observance of the Va’ad’s order.

Conflict was renewed with the appointment of Rabbi David Lida as rabbi of the Amsterdam Ashkenazi community in 1681. The rabbi quickly became the target for the anger of important members of the community who accused him of Sabbatianism and plagiarism in his book Migdal David (Amsterdam 1680). His opponents embarrassed and cursed him in public, libeled him in print, and succeeded in deposing him from the rabbinate in 1684. Close upon the commencement of the attacks against him, Rabbi Lida tried to defend himself by appealing to the Va’ad in the summer of 1681. The Va’ad did not disappoint, and its involvement is reflected in no fewer than seven documents—dated between the fall of 1681 and the late summer of 1684. We know of five letters (the first from the autumn of 1681, or 11 Tishrei 5442) that the Va’ad sent to the communities of Amsterdam, a ban against the opponents of the rabbi promulgated throughout Poland and an approbation to Rabbi Lida’s Be’er Esek, his defense and attack on his detractors. All of these reflect the Va’ad’s attempts to repel the rabbi’s nemeses and secure his position.

The Va’ad justified its intervention on behalf of Rabbi Lida, a Polish Jew, on the basis of the principle that it is forbidden to stand idly by when the honor of a sage is injured thereby injuring the honor of the Torah as well:

We have heard the sound of depravity, the sound of imprecations and curses that torture the soul of the listener. Our stomach and loins were upset, really agitated, on account of the terrible deed that was done against the honor of the great Rabbi …

In line with our Divine obligation to defend his honor, […] we have stood up and awoken and said: how can our soul not take vengeance on these evildoers? Would that they fall into our hands we would never be sated with their flesh.

As with the first two cases we described, here too the Va’ad was aware that the primary authority and responsibility in this matter lay with the local Amsterdam Jewish institutions and authorities. It was in fact preferable that they deal with it:

For now, however, we have checked our power in favor of Your Honors [the Ashkenazi community in Amsterdam] for Your Honors have the power to make a clear-cut judgement and we support Your Honors in whatever you will do in this case.

Despite these words, the Va’ad in fact could not restrain itself and decided to declare a ban on the rabbi’s attackers. The ban was to remain in force until three conditions were fulfilled. The attackers were to retract their accusations against Rabbi Lida; mollify him; and appear personally before the Va’ad to request nullification of the ban.

This ban against the slanderers and inventers of lies should be declared to the madding crowd with trumpets and shofar blast, naming the names (known to Your Honors) of those not worthy of blessing. As the evildoers are found, you have the authority to issue judgement against their persons and to confiscate their property. We here have no power but that of our mouth, with God’s counsel declaring the ban.

In other words, it was up to the Jewish leaders of Amsterdam to identify to whom precisely the ban should apply—and then to apply it.

Later, in 1684, when a compromise was reached and Rabbi Lida briefly resumed his position, the Va’ad threatened:

And if, God forbid, this rabbi will endure any slight in word or deed—whether aimed at his property or, God forbid, his person—then know well that we will come out against you with sharp condemnation.

The Rabbi Lida affair ended in 1684 with his final removal from the Amsterdam Ashkenazi rabbinate. He remained in Amsterdam, however, until 1687 when he reached a compromise with his opponents, received compensation in the amount of 250 florins and left Amsterdam for good. In this case, too, it is impossible to claim that the orders of the Va’ad led to the resolution of the conflict. The rabbi’s opponents evidently regarded the Va’ad’s bans as no more than a nuisance. No one from Amsterdam appeared either before the Va’ad or the rabbinic tribunal as it had demanded. As against the position of the Va’ad, the affair ended in the victory of the rabbi’s attackers and his exit from the city.

***

The immigation to Jerusalem of Rabbi Judah Hasid’s group in 1700 fomented unrest among the Ashkenazim of the city. The “Hasidim,” headed by Haim Malakh, became the dominant camp in the community. Their Sabbatian tendencies elicited strong opposition from Jerusalem’s Ashkenazi rabbis who, in 1705, turned to the Va’ad (as well as to some important Ashkenazi rabbis elsewhere) requesting support in their attempt to expel the Sabbatian sect from the holy city. They wrote:

Without the cooperation of the greats abroad, we do not have enough power, here in the holy city, to harass them or to condemn them to expulsion. Therefore it is incumbent upon you [i.e., the foreign rabbis and the Va’ad] to understand and be wise enough to fix what they have perverted and ruined, to proclaim and announce everywhere there is a viable Jewish community or to publicize beautiful sayings with metal pen and lead. And God forbid, God forbid, to mention the names of the signatories to this petition.

The Ashkenazi rabbis of Jerusalem were in a weak and defensive position—so much so that they were afraid to publish the names of those opposed to the Sabbatians. They believed that their only chance to prevail was to receive support from important leaders in Europe. They asked the Va’ad to declare a ban on Haim Malakh and his circle and to publicize it throughout the Diaspora. The Va’ad’s response has not survived. Once these Hasidim’s Sabbatianism became known, as early as 1701 (less than a year after their arrival in Jerusalem), the European communities had stopped sending money to the Jerusalem community. In 1704, Rabbi David Oppenheim of Prague attacked the Sabbatian group in writing, and by 1706 most had either converted to Islam or Christianity or had left the city. This was apparently somewhat due to the pressure from the Ashkenazi rabbis and their foreign supporters but resulted more so from the relentlessness of the Muslim creditors of the Jerusalem community in the city itself.

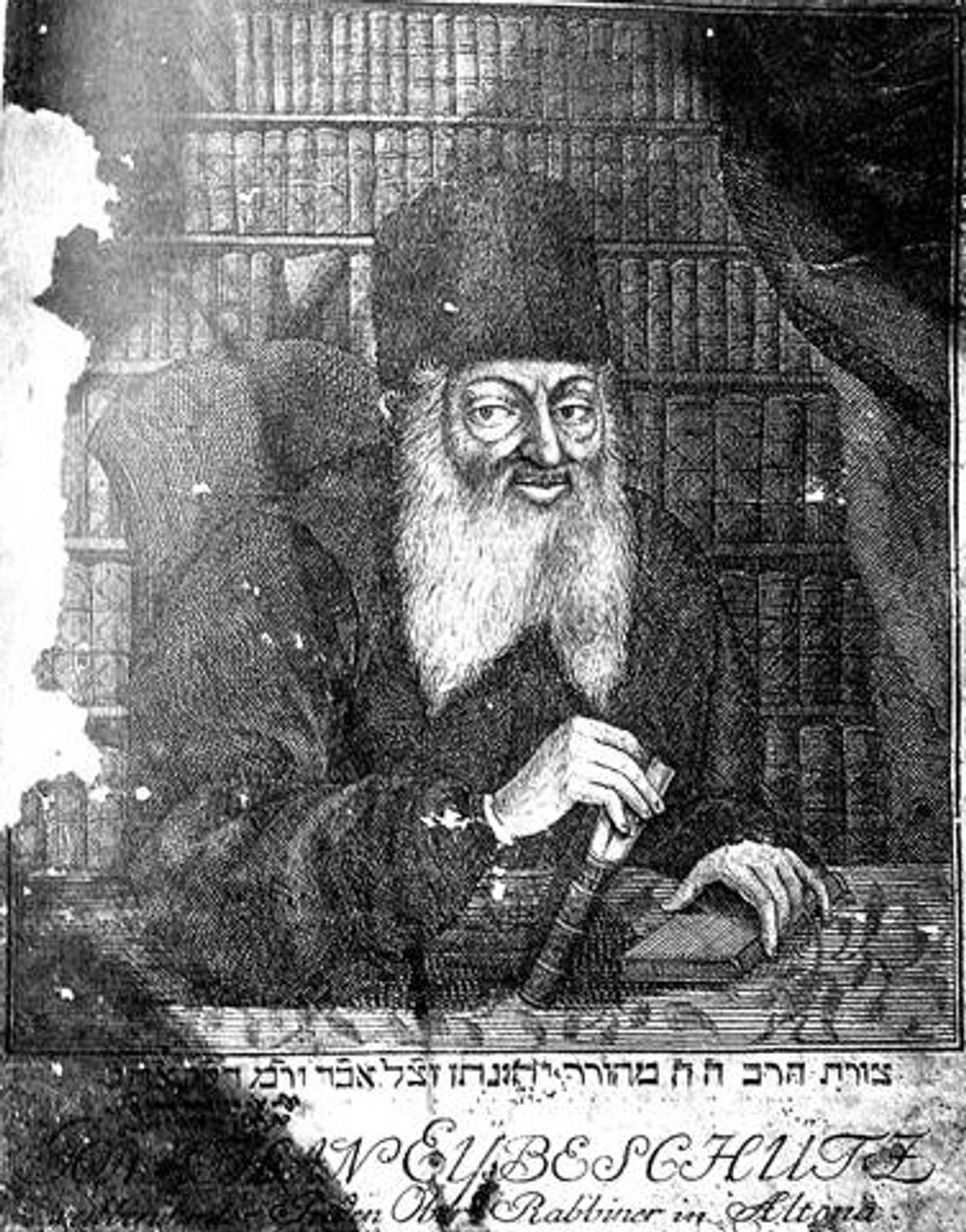

In 1751 the Va’ad became involved in the famous Emden-Eybeschutz affair. A Polish student of Rabbi Jonathan Eybeschutz, Rabbi (Ya’akov) Haim the rabbi of Lublin, and his son Avraham Haims (a well-known “politician” in the Polish Jewish communities and a candidate for a position as parnas [elder] on the Va’ad) issued a ban against Rabbi Ya’akov Emden and his supporters. This elicited a storm of protest letters addressed to the Va’ad from many Ashkenazi rabbis opposed to Eybeschutz (including Emden himself). These clamored for nullification of the ban and punishment of Rabbi Haim of Lublin by the Va’ad. They also demanded that the Va’ad join the offensive against Eybeschutz, writer of the suspect amulet inscriptions. As Emden urged

Unite with us to protect the Torah! One will declare, ‘I am for God’; one will be called by the name Jacob; one will dedicate his pen to the great and awesome God. Call to the lands both near and far: Lithuania and its region, Ruthenia, Prussia, Wallachia, and the lands of the East; to the place where your word, the word of the King, the Lord of Hosts, reaches; that they take up arms, hitch up the chariot and make war against the enemies of God.”

Emden was asking the Va’ad to join the attack against Eybeschutz. He presumed that with the controversy having spread beyond the bounds of Ashkenaz proper, the Va’ad, who ruled in Poland and influenced certain communities outside of Poland, would be a valuable ally in the battle.

For his part, Eybeschutz thought that the Va’ad could help save him from his enemies. He informed the Danish king that he intended to make his case before the Va’ad. In the introduction to his book Luhot Edut (Altona 1755) he wrote:

And I said to my persecutors here: “Behold in a few days the sages of the generation, the scholars, will meet and gather at the time of the congregating of all at the Jaroslaw meeting [i.e., the semi-annual meeting of the Va’ad]. Let us bring our case before them because they are the most and the greatest in wisdom and numbers.”

Eybeschutz fully expected the Va’ad to judge in his affair and vindicate him, hoping that their verdict would force his attackers to finally leave him alone.

It seems that the men of the Va’ad were not very eager to have to choose between the Emden and Eybeschutz camps. In their responses to the urgings of both sides they tried to refrain from insulting either party and apparently hoped that the matter would conclude without the Va’ad having to render an official and unequivocal determination. In its 1751 meeting in Konstantynow the Va’ad decided not to decide. As the treasurer of the Va’ad, Yissakhar Berish Segal, wrote to one of the prominent figures in the anti-Eybeschutz camp, Rabbi Aryeh Leib of Amsterdam,

It was agreed and the leader, the elder of the month of the Va’ad, was empowered to write with reason and good sense a reply to all of the missives. And we will see how things develop, if the Gaon, our teacher Yehonatan, will feel remorse and repair what he has ruined, so much the better. But if not, then there will certainly be a great convocation of the Va’ad this year and then we will see, God willing, about being in contact on a war footing.

In other words, the Va’ad decided only that the elder Avraham ben Yoska from Lissa would formulate diplomatic replies to the advocates of both camps. In the meantime it was waiting, in the hope that Eybeschutz would mollify his opponents. If the tensions were to persist, then the Va’ad would have to reconsider its policy.

Avraham from Lissa’s letters were in fact intended to keep good relations with both sides. Already in June 1751 (4 Tammuz 5511) he wrote to Shmuel Hilman, one of those insisting on the nullification of the ban against Emden issued by Rabbi Haim of Lublin, that this ban was not declared by the Va’ad and thus “was not a ban, nor an excommunication, but only fantasy.” However, he also expressed the Va’ad’s hesitation at taking a clear-cut position:

For great turmoil is passing over all the inhabitants of the land, trampled by these rabbinic kings. Who will throw his garment between the lion and lioness when they are in heat?

In September 1751 (8 Tishrei 5512), Avraham wrote to Rabbi Emden himself (who was an in-law of one of his children). He expressed his dismay at Rabbi Haim’s ban but politely explained that the members of the Va’ad had always hoped that the conflict would end before they would have to take sides:

And we being in consultations daily, expecting to hear the voice of good tidings proclaiming, “Peace, peace”; but instead bitterness. For many send letters to us asking for ploys and strategems. But we said let neither shield nor spear be seen in Israel; our silence is better than our speech.

The next day, Yom Kippur eve, Avraham wrote to Rabbi Eybeschutz. This letter is now lost, but Eybeschutz included a summary of it among the documents he submitted to the Danish authorities. Albeit written by a partisan, it clearly indicates that Avraham tried to placate Eybeschutz and promised to protect his honor.

The primary reason the Va’ad hesitated to stake a definite position in this controversy was, apparently, that the rabbis and lay leaders could not reach consensus. Both of the warring camps organized support in Poland, with each side attempting to gain leverage for its hero. Eybeschutz’s faction won when Avraham from Lublin (Haim’s son) was appointed elder of the Va’ad. At the end of the Va’ad meeting held in autumn 1753 he raised the issue and succeeded in forging a majority of 19 vs. 11 voting to proclaim Rabbi Eybeschutz “innocent” and condemning all pamphlets published against him to the fire.

While both camps coveted a ban from the Va’ad that favored their side, the practical value of such a ban was limited. Certainly, Eybeschutz’s hope that the Va’ad’s ban would muzzle Emden and his supporters was vain. The conflict was resolved only after the Danish king’s intervention, which led to the renewed choice of Eybeschutz as rabbi of Altona and the effective end of the controversy.

***

These and related cases allow for a few generalizations concerning the authority of the Va’ad outside of Poland, and can be divided into two clear categories: disputes between two different communities or between two factions within the same community (Group A) or interpersonal theological-ideological-commercial conflicts, in which rabbis and leaders from a number of communities were involved (Group B).

At the beginning of this article I asked what circumstances led to the Va’ad’s intervention in the affairs of a community outside of Poland. The examples in Group A offer a clear answer: In every case a community or a faction sought to dominate another community or faction or violate its prerogatives, and the beleaguered party appealed to the Va’ad in an attempt to secure backing in its fight against the “violator.” In no case did both parties decide together to appoint the Va’ad as a mediator or arbitrator in their dispute. The model was that the weaker party always tried to enlist the Va’ad in its struggle against the stronger one. Thus the opponents of the new government-appointed council of 14 in Frankfurt asked the Va’ad to revoke its legitimacy. The Polish Jews in Amsterdam wanted to preserve their separate status in the face of the larger Ashkenazi community’s desire to incorporate them. Rabbi David Lida and his supporters needed to defend themselves from the attacks of dominant leaders of the Amsterdam Ashkenazi community. The Ashkenazi rabbis of Jerusalem needed to undermine the power of the Sabbatian Hasidim who had taken over the community.

It is likely that the weaker party in each of these cases understood that alone it could not successfully resist its stronger, more influential, or more politically powerful rival. Therefore it sought out an independent outside authority that the rival would also have to respect. Notably, in most of these episodes at some point the non-Jewish governmental authorities became involved. In the case of the Sabbatians in Jerusalem, when the weaker party appealed to the Va’ad they also appealed to other communities or rabbis. This implies that when the institutions of the local community were not able to resolve disputes and restore order and stability, the Va’ad was not the sole or default option; it was one of the possible authorities that could be called upon.

Consideration of Group B where, in addition to the Va’ad, rabbis from several other communities interceded as well, also demonstrates that the Va’ad did not interfere on its own initiative. The Va’ad was asked to act by people with a material interest in the outcome of the dispute and the appeal came after other agents had already taken a position. However, the objective of the petitioners to the Va’ad in the Group B cases was not always the same as that of those in Group A.

Rabbi Eybeschutz, who saw himself as persecuted, apparently hoped that the Va’ad would serve as a court that would establish and proclaim his innocence. Here there is similarity with the weak parties of Group A. However, Eybeschutz’s antagonists, Emden’s supporters, and the protagonists in other Group B type conflicts not detailed above did not turn to the Va’ad as a court or arbitrator but as a prestigious institution that was an attractive addition to the list of those who had endorsed their cause. For them, the Va’ad was one ally (to be sure, an important one) among many. Its usefulness was in its presumed influence over others who might join the cause and not in its putative power to issue a definitive ruling that would compel the opposition to give in.

In short, our examples indicate that the Va’ad was asked to intervene beyond the boundaries of Poland-Lithuania either as an independent, outside coercive authority in a local dispute or as the ally of one side in a supralocal controversy. Such intervention was always by invitation of one of the parties and not at the Va’ad’s own initiative. Those who recognized the Va’ad’s right to interpose in matters outside of its geographic purview based their expectations on the greatness in Torah of the rabbis associated with the Va’ad. It was their greatness in Torah that entitled the Va’ad to “join the pieces of the tent into a whole”; that is, to issue binding decisions. As Rabbi Eybeschutz confirmed, the men of the Va’ad were “the most and the greatest in wisdom and numbers.”

Greatness in Torah may lend prestige or attract appeals for support; it is not necessarily a substitute for officially recognized, institutionalized authority. Several of our examples illustrate how this gap bothered the Va’ad. Even as it was mixing in, it would declare that by rights the dispute at hand should remain subject to the local authorities. If, despite this, the Va’ad intervened it was, above all, because it was asked. In contrast to those who appealed to it, the Va’ad did not emphasize its superior Torah standing. In fact its messages contained conventional praise for the Torah honor of Amsterdam and Frankfurt. The Va’ad certainly did not assert that its status in Torah mandated obedience to its word.

As a practical matter, the purpose of appealing to the Va’ad was to elicit a ruling or a ban in the petitioner’s favor and against his rivals. In most of our cases, the Va’ad complied. However, with the exception of the initial 1665 directive to the Sephardim of Amsterdam to support the Polish community there (a position that advanced the Sephardim’s interests), the intervention of the Va’ad in the cases of our sample produced no demonstrable result. The absence of strong sanctions prevented the Va’ad from fulfilling the expectations of those who appealed to it: to force a ruling on the opposing party.

At the beginning of this article I asserted that the Va’ad enjoyed moral authority outside of Poland-Lithuania. Analysis of the cases presented here demonstrates that this authority was anchored in the Torah reputations of the Polish sages. This is somewhat ironic given that, as already noted, the Va’ad was primarily a lay body and its enactments were in the genre of law and not rabbinic responsa. Nonetheless the Va’ad did command a certain moral authority that lent it a status comparable to that of non-Jewish governmental institutions (and certain great rabbis) in the eyes of weak parties in local conflicts. In practice, however, the Va’ad’s moral authority was not sufficient to be able to achieve this aim. Jews the world over may have heard of the Va’ad, admired it, even might try to enlist it in their cause when needed. Their willingness to respect the decisions of the Va’ad seems to have been in direct proportion to the degree to which the Va’ad supported them and their interests.

***

A longer version of this article appeared in Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, vol. 22 (2010), pp. 83-108.

Moshe Rosman, a professor in the Department of Jewish History at Bar Ilan University, is the author of How Jewish is Jewish History? and, most recently, a new edition of Founder of Hasidism: A Quest for the Historical Ba’al Shem Tov.

Moshe Rosman, a professor in the Department of Jewish History at Bar Ilan University, is the author ofHow Jewish is Jewish History? and, most recently, a new edition of Founder of Hasidism: A Quest for the Historical Ba’al Shem Tov.