Cracking the Voynich Code

The quixotic quest to read meaning in the patterns of a bizarre manuscript that has bedeviled scholars for years

The Tablet Longform newsletter highlights the best longform pieces from Tablet magazine. Sign up here to receive occasional bulletins about fiction, features, profiles, and more.

A mysterious manuscript has plagued historians, mathematicians, linguists, physicists, cryptologists, curators, art historians, programmers, and lay enthusiasts alike since an antiquarian and book dealer named Wilfrid Voynich first began to mention it in his correspondence in 1912. Voynich maintained that it was the work of a 13th-century English philosopher, Roger Bacon. Written in an unknown script and replete with pictures and diagrams, and now residing at the Beinecke Library at Yale, the Voynich Manuscript has become a beacon for a secular community of quasi-Talmudic scholars whose interpretive ingenuity and stamina have few parallels.

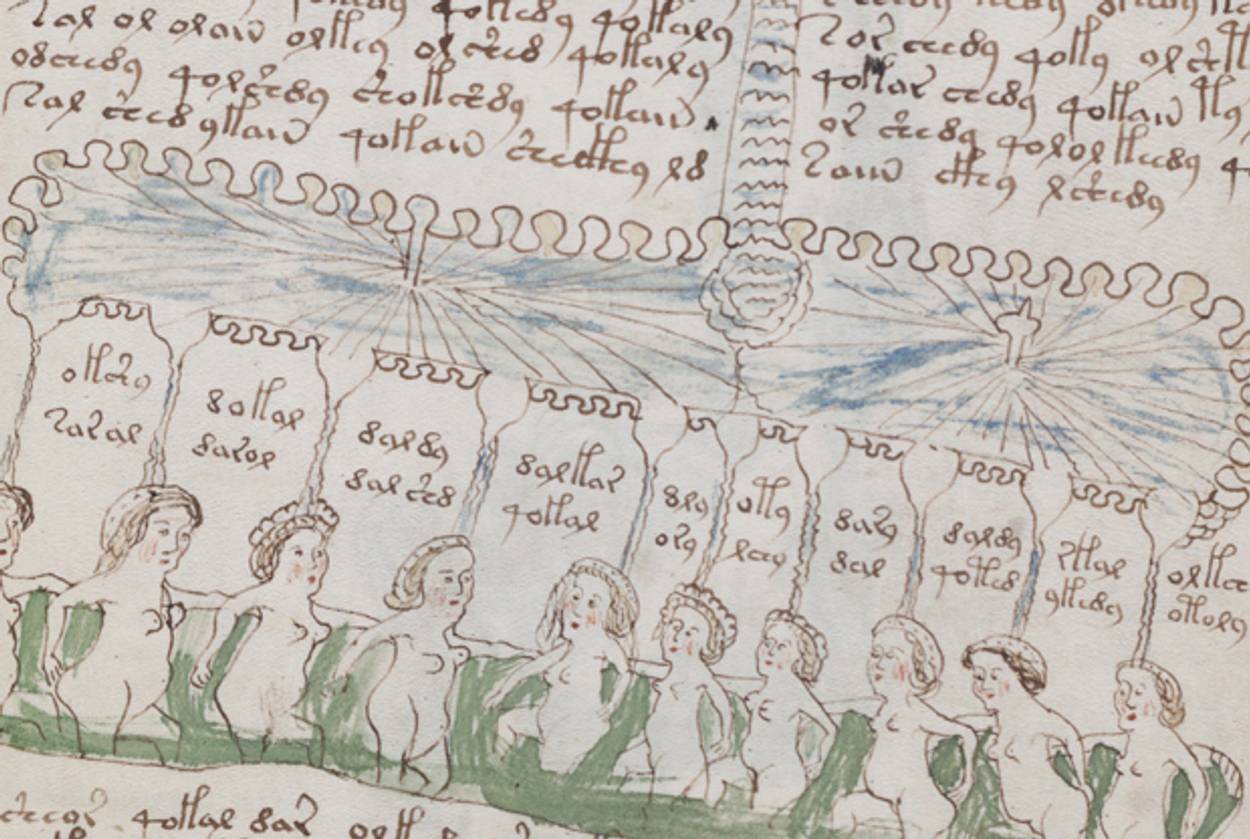

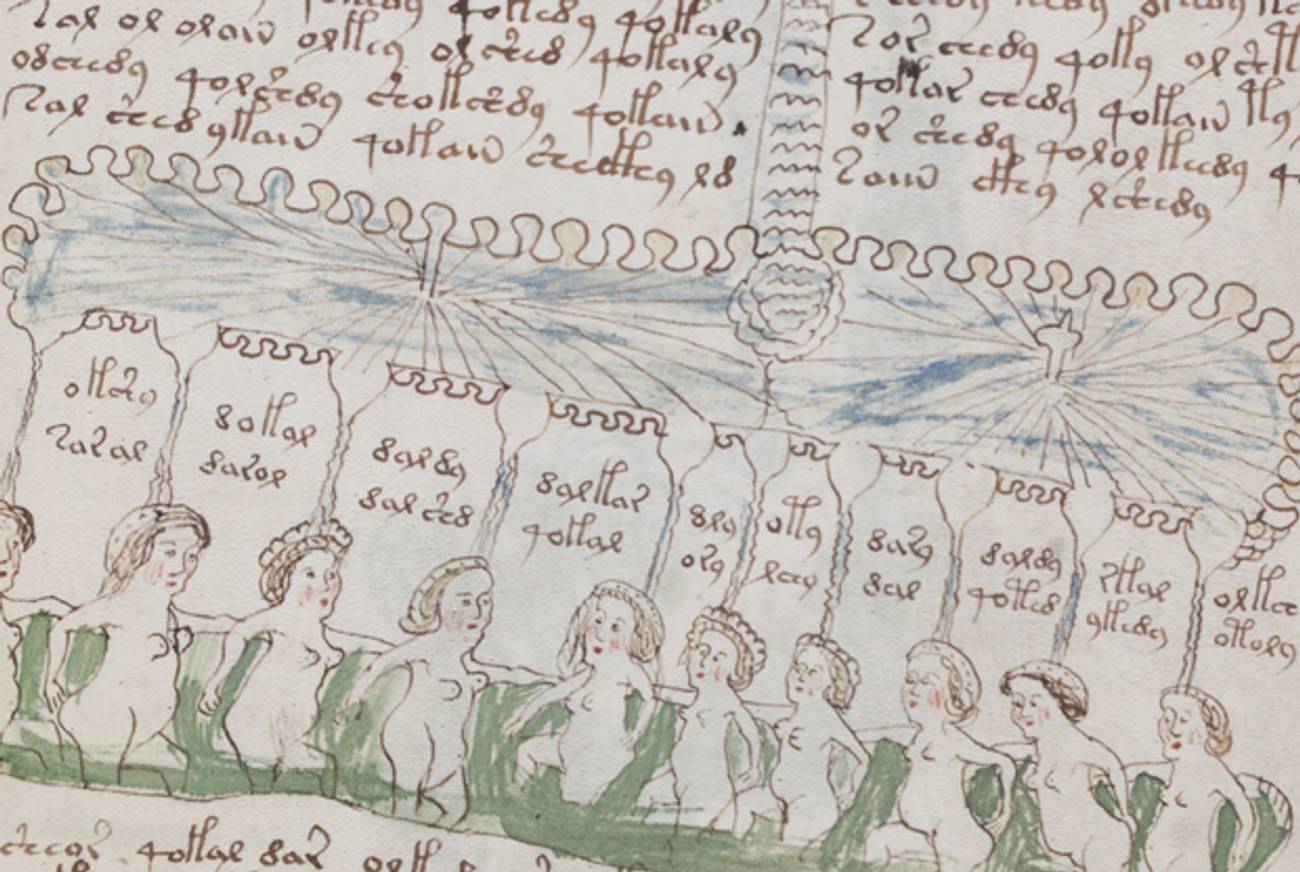

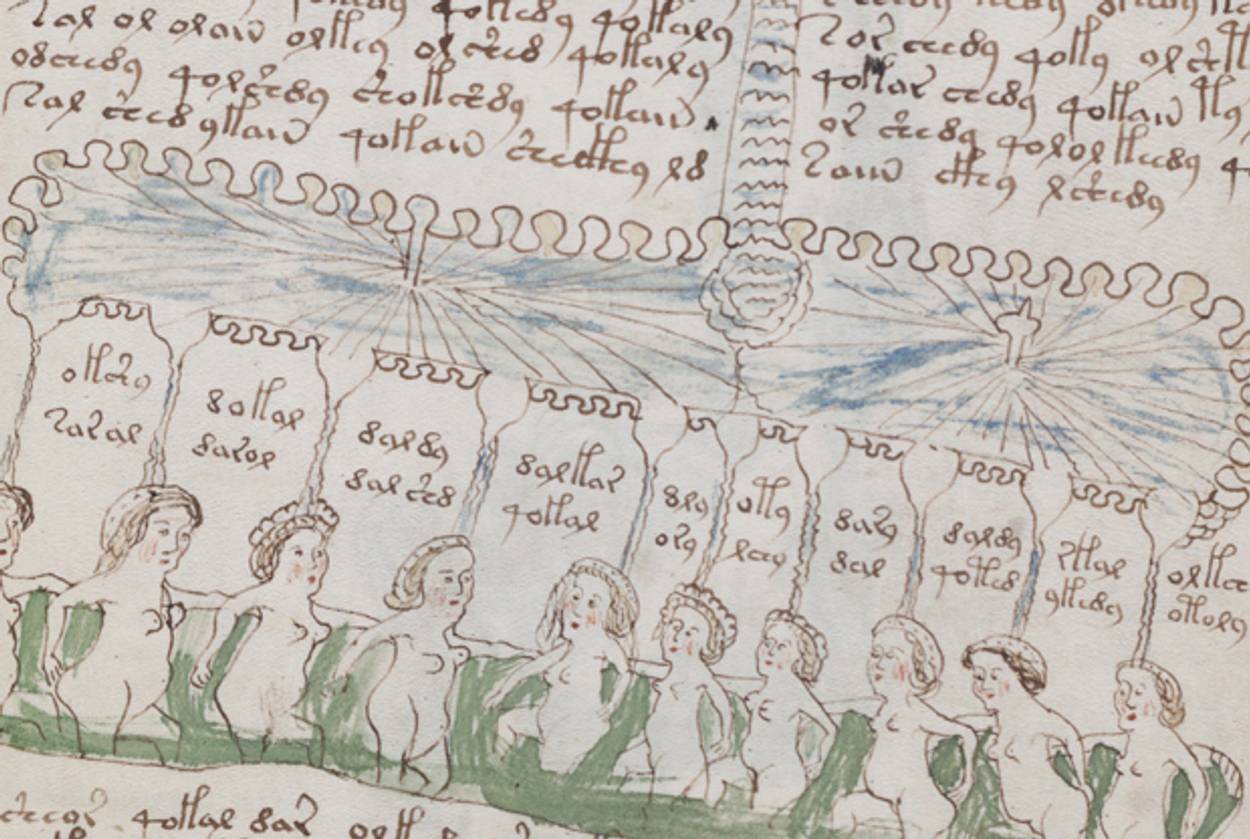

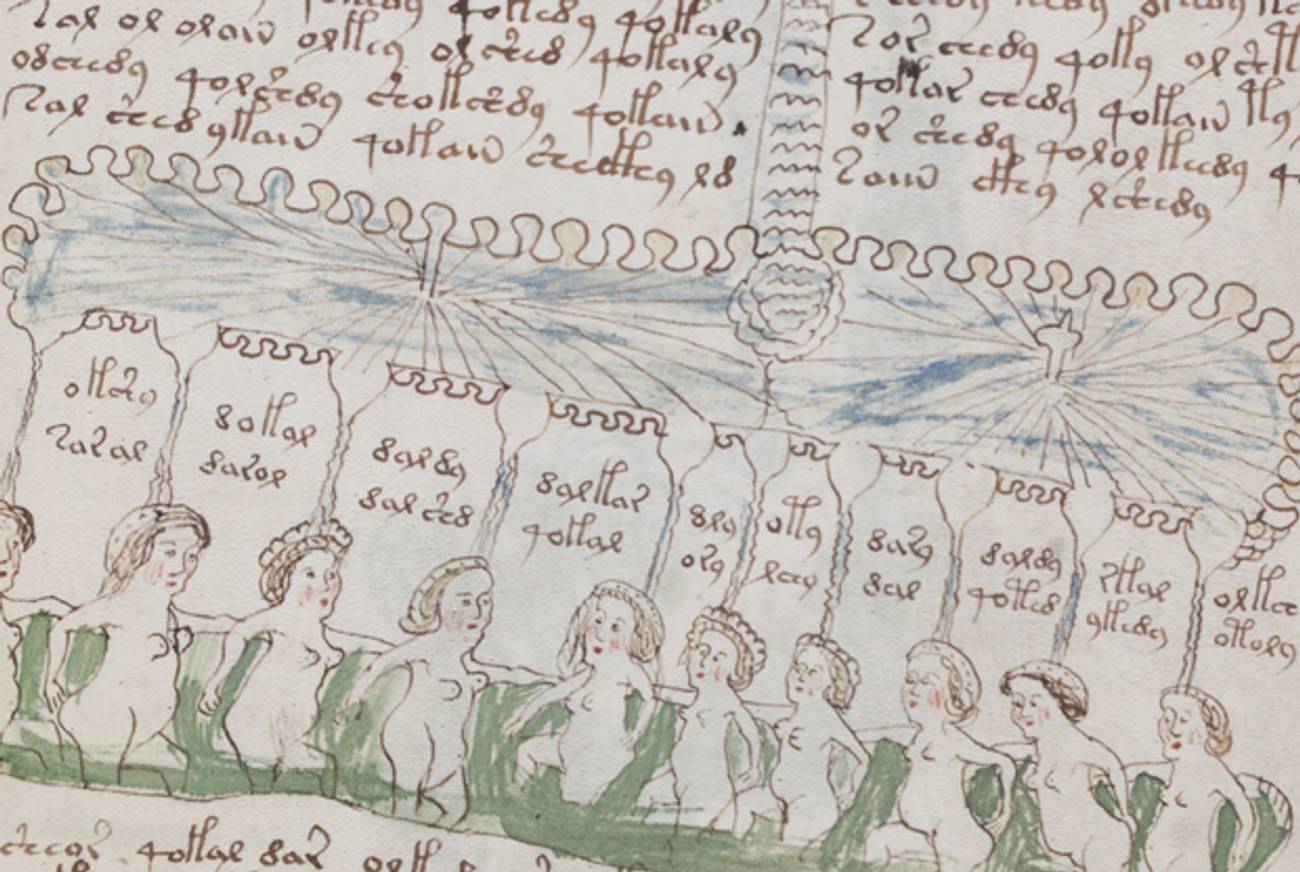

The manuscript is a small book—23 x 16 centimeters (about the size of a small volume of Penguin Classics)—of around 240 pages. It is written in a code made up of an alphabet of between 20 and 30 characters, depending on the transcription. Most of the pages also bear illustrations: large-leafed plants, long tubes, astrological charts, a few goats, and many, many naked ladies bathing in pools and holding hands. Compared to the careful and sophisticated nature of the calligraphy, the drawings are primitive, even crude, a child’s assessment of the female form. (One of the women looks vaguely annoyed, her hands inserted into two pipes, a small beard sprouting from her chin.) The plants, like the language—dubbed “Voynichese”—give off a frustrating and titillating feeling of familiarity, one recorded by experts, many of whom concur when asked how they got hooked on the Voynich: “It just looked so easy,” they say.

Perhaps the manuscript’s most famous wooer was William F. Friedman, a Jewish U.S. Army cryptographer, who is considered one of the foremost code-breakers of all time. Born Wolf Friedman in Kishinev, Bessarabia, to a father who worked as a translator for the Russian Postal Service—Friedman Sr. reportedly knew eight languages—Wolf’s name was changed to William after the family immigrated to Pittsburgh in 1892. While working as a geneticist in the 1920s, he met Elizabeth Smith, a cryptographer who helped break codes for the government in order to expose communists and drug runners during Prohibition. They met when Smith was working for Elizabeth Wells Gallup, who was trying to prove that there were hidden cyphers in Shakespeare’s works, which Gallup believed were composed by Francis Bacon.

During World War I Friedman worked for the U.S. Army to break German codes, and in 1940 he led the team that broke PURPLE, a Japanese cryptographic machine used to convert messages into code, which was believed unbreakable (the Japanese didn’t believe the Germans who told them that the Americans had cracked it and continued using PURPLE long after the Americans had already procured one of the machines). He spent the rest of his life, or something close to it, obsessed with the Voynich. Friedman broke PURPLE, but he did not break Voynich.

Last year, a group of scholars convened for the centenary of Voynich’s purchase of the manuscript. The Voynich 100 Conference was held at the Villa Mondragone, where a 1960 letter claims Voynich purchased the manuscript (though during his life, he told a different tale). New data about the manuscript were floated, as well as linguistic analyses of its syllable structure, the possible presence of microscopes in the manuscript’s illustrations, and a forensic investigation into the parchment upon which it is inked. But no firm conclusion was drawn. After 100 years, the manuscript’s language still has yet to be deciphered.

***

Wilfrid Voynich, born Wilfridas Mykolas Vojničius, had a life filled with instances of the uncanny. A Lithuanian pharmacist, Voynich was imprisoned for his role in revolutionary attempts to free Poland from Russian rule. While serving a two-year prison sentence, Voynich looked out the window of his cell one day and caught sight of a blonde in a black dress. Two years later, after escaping from a Siberian prison and arriving penniless in London (he had to sell his waistcoat and glasses for a third-class ticket and a piece of herring, the story goes), he found that same woman in the home of his contact, another revolutionary. She was Ethel Lillian Boole, daughter of the famous mathematician George Boole, and a revolutionary in her own right. They were married, and Voynich managed to become, quite mysteriously, a recognized antiques dealer in just eight short years.

Voynich told people he thought that the manuscript that now bears his name had been written by Roger Bacon, the famous 13th-century philosopher and Franciscan. But he kept the location from which he claimed to have bought the manuscript a secret, naming another place altogether—the Villa Mondragone, he wrote in a letter to his wife, which was only disclosed after her death by her companion, Anne Nill. During his life, Voynich claimed to have bought the manuscript in “an Austrian Castle.”

Beyond that, there are few clues. A letter in the inside cover of the book addresses Father Kircher, a German Jesuit with a penchant for (wrongly) translating hieroglyphics and (correctly) establishing the link between Coptic languages and Egyptology. The letter is signed and dated Johannes Marcus Marci, Prague, 19 August 1665 (or 1666—it is curiously ambiguous). Marci was the official doctor of the Holy Roman Emperors Ferdinand and Leopold. The book, he says in the letter, was bequeathed by an old friend, who devoted his life to deciphering it, unsuccessfully, for “such Sphinxes as these obey no-one but their master, Kircher.”

Kircher was not up to the task, and neither was Friedman, who never published anything on the Voynich save a footnote to a paper on Chaucer that he and his wife wrote for Philological Quarterly. The footnote was anagrammed (in the tradition of Galileo’s repudiation of Ptolemy), with its solution provided in a sealed envelope for later disclosure, when Friedman believed he would have solved the cypher. The anagram, which reaches the limit of Friedman’s sense of humor, reads, “I put no trust in anagrammatic acrostic cyphers, for they are of little real value—a waste—and may prove nothing.—Finis.” Readers wrote in possible solutions, some delightfully reprinted in an editor’s note (“To arrive at a solution of the Voynich Manuscript, try these general tactics: a song, a punt, a prayer. William F. Friedman.” Or “This is a trap, not a trot. Actually I can see no apt way of unraveling the rare Voynich Manuscript. For me, defeat is grim.”) Friedman never managed to solve the Voynich, and after his death, the editor of Philological Quarterly opened the envelope bearing the solution to the anagram: “The Voynich Manuscript was an early attempt to construct an artificial or universal language of the A-Priori type.—Friedman.” A synthetic language, rather than a cryptogram, was his best guess.

One of Friedman’s most important publications focused on the role of statistics in cryptoanalysis. In Voynich scholarship, all are in agreement that statistics matter. The difference between these analyses lies less in the statistics themselves and more in their analysis. Most experts concur that there is a syllable structure to be found, as well as the reccurrence of prefixes and suffixes. Jorge Stolfi, a professor of computer science at the State University of Campinas, Brazil, composed a grammar for Voynichese and concluded that it behaves like a natural language, more so than like a code, as many others believe. “I am a bit of an outlier,” he told me on the phone. “I think there is a linguistic message.” The statistics, he elaborates, point to an Asian language like Chinese, short words with tonal structures. His theory is that someone went to the Far East and phonetically transcribed something he heard or read. “It is not unusual at that time to make up an alphabet to record a foreign language,” he said. Stolfi presented at the 2012 Voynich 100 Conference, and his research has made a deep impact on some. René Zandbergen, one of the conference’s organizers, considers it to be one of the biggest inroads in recent attempts to solve the mystery of the manuscript.

But the existence of a pattern does not necessarily mean that Voynichese is a natural language. There is a bit of a logical fallacy at play in assuming that just because the cipher is not random, that it is therefore linguistic. Indeed, the non-randomness of syllable distribution is exactly what one would expect from a hoax, according analysts like Andreas Schinner. When I asked Schinner, a theoretical physicist, how he got involved with the Voynich Manuscript, he replied, “At first I was just fascinated by the sometimes ridiculous, often tragic-comical efforts of the VMS enthusiasts. I never expected to find out something useful myself. But as often, things are found by someone, who does not really search, rather than someone, who is too enthusiastic.”

What Schinner found was that, contrary to Stolfi’s analysis of the statistics of Voynichese, the language did not operate as other natural languages do. “You can see any text as a long string of symbols,” Schinner explained. “Then you can ask several statistical questions: How are symbols and symbol groups (substrings) distributed, how are they correlated?” Schinner did just that to the Voynich and found “that the Voynich Manuscript ‘language’ is very different from human writings, even from ‘exotic’ languages like Chinese. In fact, the results better fit to a ‘stochastic process’ (a sequence of correlated random events).” In an article in Cryptologia, he concluded that the Voynich contains no encrypted message at all.

But why would someone create such a document? Schinner thinks the most probable reason for creating such a hoax would be for the purpose of selling it. “However,” he added in our email correspondence, “I like the idea that it might have been created as an artwork.”

Another Voynich scholar, Gordon Rugg, also believes that the statistical analysis reveals the manuscript to be a hoax. Rugg is a psychologist by training who studies how humans interact with technology. He specializes in locating the bugs in human reasoning. “In all fields, humans make the same mistakes,” Rugg said over the phone. “We make faulty assumptions that are totally plausible,” especially in research areas where different disciplines overlap. For example, many disciplines rely on statistics, yet many experts in those fields do not understand statistics, resulting in mistakes. Other sorts of errors occur precisely where intuitive knowledge is used. People make category errors, or they default to the most common option, or they fall prey to the dreaded yet ubiquitous confirmation bias, testing only for evidence consistent with their hypothesis.

Rugg’s aim is twofold—to analyze the errors in expert reasoning, but also to generate models that represent knowledge to help correct those errors and convey more accurately the complex units of different fields. To this end, he has designed among other things a computer program called “Search Visualizer” (a version is free online) that generates a visual representation of a text, revealing structural properties and patterns that were previously invisible, even to experts. Rugg calls his process the “Verifier” approach, for verifying expert reasoning. If you want to solve a problem, the theory goes, look at how experts who have failed to do so have worked. You will soon find an error whose correction yields results—or, you will if you are Gordon Rugg.

There is a playfulness to Rugg’s manner that masks the rigor of his thought process. It is the manner that accompanies people willing to consider all options, those few who truly apply the scientific method to their own thought patterns. He originally became interested in the Voynich Manuscript as a hobby—“like a crossword puzzle”—and then as a good way to show students how to narrow down a research question and utilize the scientific method. His teaching style is patient, tireless; I got a taste of it as he took me again and again through the intricacies of the Verifier approach. He thanked me repeatedly for “making him think about what he is doing in new ways,” despite the fact that it was mostly the old ways that I kept badgering him for more of.

Too weird to be a language, but too complex to be a hoax

Like Andreas Schinner, who called the Voynich Manuscript a “precious mirror to human reasoning,” Rugg sees approaches to decoding the Voynich as illustrative of the kinds of typical errors in reasoning that humans make, especially when using technology, and especially when cross-utilizing information from different disciplines. Rugg found himself wanting to tackle Alzheimer’s, a famously opaque and cross-disciplinary problem, but he needed a test case. The Voynich was perfect.

Rugg began by analyzing the reasoning used by the experts who had as yet failed to decipher the manuscript. He found that the prevailing notion, that the manuscript represents an encoded message, was based on a certain analytic, namely, that it was too weird to be a language, but too complex to be a hoax; therefore, the reasoning went, it must be a code. Because the idea of a hoax was so easily discarded, it flashed like a red light for Rugg, who proceeded to teach himself Voynichese (“I can now write Voynichese faster than I can write English,” he told me) and to investigate how hard it would be to create the manuscript from scratch. Using a simple table and grille (a chart of letters, and a square paper with two boxes cut out), Rugg was able to recreate the Voynich Manuscript in a manner of months, syllable structure, drawings, and all.

Between our first and second conversations, Rugg put some common Voynichese syllables into the Search Visualizer program. The results were staggering. While natural languages have an even distribution of common suffixes and prefixes, common prefixes and suffixes of the Voynich Manuscript are clustered in different parts of the text. But perhaps even more astonishing is the distribution of four parallel charts with four different syllables: The clusters all align. The banding of syllables—where they change frequency quite radically—all occur at the same place in the text. While this is radically inconsistent with natural languages, it is quite consistent with the table and grille method of producing words, in which, to create the illusion of a language, the writer would turn the grille on its axis to start creating a new frequency. Imagine trying to fool people into believing that you lived in a certain neighborhood. You might come into work every day bearing coffee from a café in that neighborhood. But they might catch on. So one day, after a month or so, you come in with lunch from an eatery in that neighborhood. You do that for a while, and then start purchasing books from a local bookstore. In the same manner, turning the grille gives a new set of prefixes and suffixes, so that the illusion is maintained, and words aren’t repeated too much.

“After a few weeks, we found something no one else had seen,” Rugg says. His book, The Blind Spot, is due out in May, and has a chapter on the Voynich.

***

In 2000, a second letter mentioning a mysterious book in code and addressed to Sphinx master Kircher was found. René Zandbergen, an engineer by trade with a website about the Voynich, discovered it in Kircher’s letters. Georg Baresch, an antiques dealer, wrote to Father Kircher in 1639 (for the second time), asking him to take an interest in a mysterious manuscript that he couldn’t decipher. He hoped that Kircher, who “burns with a publication of things which are good, will not disdain from revealing also those things which are good in his books, buried in unknown characters.” Like Marci, Baresch seemed to think Kircher alone capable of deciphering the text, “given that here there is nobody capable of lifting such a weight, which consists of such obscure material that it requires a special genius.” The letter suggests, “from the pictures of herbs, of which the number in the Codex is enormous, of various images, of stars and of other things which appear like chemical secrets, I conjecture that it is all of medical nature.” This led Zandbergen to conclude that the manuscript described was the Voynich. Because “all details he mentions (unknown writing, herbs, stars) fit as well, there can be no doubt at all,” he wrote in an email.

Voynich’s contention that the book was written by Roger Bacon came from Marci’s letter, which was inside the manuscript when Voynich presented it for the first time at a Chicago Art Institute exhibition in 1915. The letter mentions that “Dr. Raphael, tutor in the Bohemian language to Ferdinand III, then King of Bohemia, told me the said book had belonged to the Emperor Rudolph and that he presented the bearer who brought him the book 600 ducats. He believed the author was Roger Bacon, the Englishman.” A signature on one of the pages also seems to suggest that the manuscript was once in or around the court of Rudolf II. The name “Jacobus de Tepenec” appears on the first page. Tepenec was a pharmacist of Rudolf’s.

Born in 1552, King Rudolf II of Bohemia was prone to bouts of melancholia, which led him to consort with doctors of the occult, such as Edward Kelly, a known alchemist and spiritualist, and John Dee, a consultant in Queen Elizabeth’s court on all things mathematical, astronomical, and alchemical. The two worked closely to communicate with angels, Kelly transcribing whole books in the Enochian language with which they spoke to him. The relationship lasted until one day, while consulting with the spirits, “Kelly pretended to be shocked at their language, and refused to tell Dee what they had said,” according to Charles Mackay’s 1848 Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. Upon Dee’s insistence, Kelly told him that, according to the angels, the two men “were henceforth to have their wives in common. Dee, a little startled, inquired whether the spirits might not mean that they were to live in common harmony and good-will? Kelly with apparent reluctance, said the spirits insisted upon the literal interpretation.” It marked the end of the friendship.

Interestingly, the parchment, when radiocarbon dated, revealed what seemed to be a different conclusion than the one suggested by the 16th-century paper trail. In 2011, physicist Gregory Hodgins of the University of Arizona sampled four of the Voynich Manuscript’s pages: the page with Tepenec’s signature, one of the foldouts, and two pages bearing the two handwritings noticed by experts. Because the unstable form of carbon, or C14, decays at a known rate from the day that an animal or plant dies, its measurement can yield a time frame of death, Hodgins explained to me patiently on the phone. This time frame is then compared to a database assembled of known C14 measurements gathered from trees, whose rings correspond to years. “Radiocarbon dating is not accurate, but it is precise,” Hodgins explained. “There is a true value to what we are measuring, even if we don’t know what our target is before we begin the process.”

What he found when sampling the Voynich Manuscript was even more precise than usual, due to a fortuitous accident of nature. C14 levels are contingent upon external factors as well, such as cosmic rays and changes in atmosphere. In the 16th century, for example, C14 had stabilized relatively, making it harder to radiocarbon date things within less than a 100-year time frame. The change in C14 was simply too slow. But the animal upon whose skin the Voynich Manuscript is written died in a century during which the rate of decay enabled a very precise window. Hodgins estimates with 95 percent certainty that the animal died between 1404 and 1438.

This date, roughly 150 years before that suggested by the Tepenec signature, has led many experts to conclude that the manuscript must have been written in the 15th century. “It’s just logic,” said Paula Zyats, assistant chief conservator of the Yale Library. “Velum was too expensive to leave untouched. It did not get wasted; the opposite—it was used over and over. Nobody lost a big chunk of parchment.” Zandbergen too thinks that the radiocarbon date provides ample evidence for an early-1400s date. In Hodgins’ experience, forgeries tend to get different results on different pages, whereas with the Voynich Manuscript, all four pages overlapped in a 34-year period. “It’s possible that they came from different skins, but the four samples are very closely tied together,” Hodgins said. “Why would someone buy two-hundred-year-old paper?” Stolfi asked me. “That would be equally mysterious.”

Does a radiocarbon date really rule out the possibility that a talented hoaxer might have procured old vellum in order to perpetrate a hoax? Do letters mentioning an undecipherable manuscript necessarily describe this undecipherable one? Or are all these simply the errors in reasoning made when experts from one field assume the conclusions of another?

Ink cannot be dated—so the date that the vellum was written on cannot be confirmed. But for Gordon Rugg, the biggest blind spot in Voynich scholarship has been the assumption that ink went onto fresh vellum. Rugg thinks the most likely culprit for penning the manuscript is Edward Kelley, of wife-swapping fame, well-seasoned in creating made-up languages and perpetrating frauds and hoaxes. (He had his ears cropped for forgery, a common punishment, which he spent his life covering up with ingenious hairstyles.) But once the suspect assumption that the manuscript was written on fresh velum is done away with, is there any reason that the 16th century becomes more compelling than, say, the 17th century? Or the 20th century?

Rich SantaColoma thinks not. SantaColoma is another Voynich scholar, a former jeweler, a current writer, and a sometime historian. “I do all sorts of things,” he told me recently in a café in the New York’s Village. A jack of all trades, he lives Upstate, where he curates the Voynich mailing list. SantaColoma is a deeply humble man who exudes an openness and curiosity about the world around him. At one point he became engrossed in the benches we sat on, wondering where they must have come from. (“They are pews of some kind. And what about those paintings? Do you think they are real? I mean, obviously they are real, but from when?”) He told me that when he first heard of the theories surrounding strange relics in Michigan Copper Mines, he immediately began to research those, too; “they had solved them. Otherwise, my wife and I would have jumped on our motorbikes and headed out there to check it out!” About the Voynich, SantaColoma says with admiration, “It’s still a mystery, after all this time.”

On his blog, SantaColoma listens to everyone, even people who he thinks are probably wrong. “Who knows what golden nugget one might discover from someone who has been thinking freely about the subject? You have to encourage people to contribute, to openly share ideas. That’s how Michael Ventris solved Linear B!”

Like Rugg, SantaColoma was intrigued by the commonly held assumption that blank vellum wouldn’t have been available to an industrious antiques dealer. Upon further investigation, he found the assumption to be flat out wrong. He emailed me a list of six sources of blank vellum, with between 80 and 150 pages each, carbon dated as far back as the 15th century. Some were available as late as 2007, and may still be available for purchase.

“My thinking is, how can you apply existing probability to an object that is totally unique?” SantaColoma explained to me. “That’s the Voynich Manuscript problem. I don’t want to sound crazy.” He interrupted himself. I assured him he didn’t. He continued: “But I think scholarship is a hindrance in this case. Scholarship can only categorize. What happens when you have a completely unique object? It doesn’t fit any category. But the academic core of Voynich scholarship is playing it very safe.”

SantaColoma sites the uncanny feeling reported about initial encounters with the Voynich Manuscript as a crucial factor in uncovering its meaning: “Every single point is just off enough to make it seem familiar and yet be completely unidentifiable. That had to be intentional; think of how difficult it would be to create something that reminds you of something else, getting everyone to follow different directions. It must have been intentional,” he reiterates, “or the author would have given it away! They wanted it to be unidentifiable.”

“Every single point is just off enough to make it seem familiar and yet be completely unidentifiable.”

There is a category for a text that borrows heavily from reality, without itself being real: It is the category of fiction. “I think it’s fantasy,” SantaColoma says. He noticed another thing: The cylinders, which other scholars called “jars,” were actually quite similar to early microscopes—long, leather encased cylinders with glass on either side, and details along the leather. These microscopes were being created in the 17th-century, a time when there was also a resurgence of utopian, i.e., fantasy, writing. In fact, SantaColoma sees in the Voynich many similarities to Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis, a 17th-century utopian tract about a fantasy island where Bacon’s ideal college is described: the unknown plants, the grafting, the code, books on velum, and new types of animals, as well as a bath full of naked ladies.

“If you took a group of artists and gave them New Atlantis and asked them to draw a book from that place,” SantaColoma said, “it would probably look a lot like the Voynich.” As for why someone would do such a thing, SantaColoma said he didn’t know. “Maybe as a tribute, or a gift.” His theory resembles Friedman’s “artificial or universal language,” which a colleague heard Friedman compare to “the form of a philosophical classification of ideas by Bishop Wilkins in 1667 and Dalgarno a little later.”

At the centennial conference, SantaColoma presented these three observations, to the expected objections of the other scholars. Their objections boiled down to one: the slippery slope. If it could have been written in the 17th century, what’s wrong with saying it was written in the 20th century? Because he is a man who considers all possibilities, SantaColoma went home with their objections and seriously considered them. Indeed, what is wrong with saying that it was written in the 20th century? he wondered. “There is a nagging sense of newness in the manuscript,” he explained. “So people say, well, it looks new, but it can’t be new, so it must be old! But why?” he continued to ask. He recalled Robert Brumbaugh, who wrote about the Voynich in the 1970s, saying that the manuscript looked less like Bacon than like someone trying to make it look like Bacon.

But if it was not a 17th-century fantasy text, what then? Who in the 20th century could have cooked up such a hoax, and to what end? One man had the opportunity and the know-how: Wilfrid Voynich.

“I don’t want to sound crazy,” SantaColoma said, “but think about it: Voynich is a Polish revolutionary. He falls in love with Ethel Lillian Boole, an English girl working for the Russian revolutionaries. She has an affair with Sidney Reilly, the guy who James Bond is based on, a known forger, who took out books from the library on creating medieval ink. Voynich is set up in the book business, some say by the revolutionaries in order to overthrow the Russian aristocracy. There were other bizarre coincidences in his book-keeping. He had two copies of the Valturius, but only promoted one. The other was more primitive—was it a failed forgery? Voynich lived 1,300 feet from an Italian museum with 17th-century microscopes that look just like the ones in the Voynich. Are you telling me that this wonderful crazy man failed to make the connection between his mysterious manuscript and these 17th-century inventions, ruling out the possibility of a 15th-century manuscript?” SantaColoma then interrupted himself to speak to a gentleman at the table next to ours about a racing car he had overheard the man mention. (“I have one in my backyard! The trick is to keep all four wheels on the road.”)

He showed me pictures of the microscope in the Museo Galileo, just a short distance from Voynich’s Libraria. They look a lot like the tubes in the Voynich Manuscript. He points to two illustrations in the Voynich, one that looks curiously like an armadillo, and one that scholars have called a sunflower, both of which he says were New World discoveries, placing the Voynich squarely after 1492. And what about the letters mentioning the manuscript? Couldn’t Voynich, who knew of these letters, and the absence of a referent for them, have cooked up a book to look a lot like what was being described? Surely all the mystery surrounding where he purchased the book is consistent with such a narrative.

Finally, SantaColoma points out, the radiocarbon date is averaged out between all four samples, in other words, the date arrived at was done using a faulty assumption—that the book’s pages were created at the same time. As SantaColoma explained in an email, “if we had one sample only, from folio 68, the date of the Voynich would be circa 1365 to 1435, covering the range we know, but going back decades from it; and if it was one sample only from folio 8, from 1423 to 1495. So if the samples were not averaged, the range of dates given for the Voynich would have been 1365 to 1495, which as you see is quite a bit different than the announced ‘1404 to 1438’ range, which we learned was based on these average dates.”

Many experts believe that the key to the Voynich manuscript is just around the corner, but the “golden nugget,” as SantaColoma puts it, seems more likely to come from the honest skepticism he applies so liberally to his own thought processes than from an undiscovered document. If the Voynich Manuscript hides any meaning, surely it is that.

***

Sign Up for special curated mailings of the best longform content from Tablet Magazine. Fiction, features, recommended reading, and more:

Batya Ungar-Sargon is a freelance writer who lives in New York. Her Twitter feed is @bungarsargon.

Batya Ungar-Sargon is a freelance writer who lives in New York. Her Twitter feed is @bungarsargon.