Crash Course

After a lifetime of avoiding Philip Roth’s books, a reader decides to see what all the fuss is about

Until last month, I had never read anything by Philip Roth.

I’m not exactly sure how this happened. I’ve been a book nerd all my life, having grown up in a household full of crowded shelves, where the most appropriate Shabbat afternoon ritual was a trip to the library. My grandparents’ homes were full of books by the Major Jewish Writers—Bellow, Malamud, Singer, Roth—but my parents (though they both work in the Jewish world) were less interested in them.

As I got older and started writing about books professionally, Roth’s supremacy was unavoidable: He was always collecting awards, making everyone’s top-10 lists, serving as a reference point for critics talking about sex in literature, Jewish identity, misogyny, and New Jersey—all things I ostensibly cared about. His face regularly peered out from articles in newspapers and magazines, and his unsmiling face with its graying orbit of hair was familiar in a way that made me look past it and on to articles about new writers, whose books were so often positioned as rebuttals or complements to Roth’s legacy.

Not having read any Philip Roth felt alternately reprehensible and like a point of pride. Could I actually appreciate the landscape of contemporary fiction without him? On the other hand, we all have to build our own canons, and everyone’s education has its gaps, intentionally or not. (I knew I couldn’t be alone in this aspect of my under-education; there had to be plenty of well-read people who had their own reasons for having avoided him, too.) And I’ve always been skeptical whenever a author is hailed as the savior of literature, the Great American Novelist, or the embodiment of all we could hope for in a writer—whether that writer is Philip Roth or Jonathan Franzen or Zadie Smith or Roberto Bolaño. Slowly, though, the fact that I didn’t know Roth’s work started to feel like an opportunity, a rare chance to approach something with relatively few preconceptions. Sure, I knew the basics: Roth was prolific, Jewish, aging, cranky, and venerated. But how did his books read? Would I like them?

With his 31st book, Nemesis, arriving this month, catching up on him completely was a daunting and not entirely pleasant prospect. And I didn’t really want to try. After all, if I wanted to fully understand Roth and his intimidating oeuvre, I would read all 31 of those books, along with critical biographies and anthologies and interviews that detailed the experience of reading him from just about every possible perspective, along with Claire Bloom’s scathing memoir of their relationship, Leaving a Doll’s House. I would read through hundreds of reviews and consult the experts at the Philip Roth Society. Instead, I just wanted to find out what it was like to persist on a Philip Roth diet for a few weeks, to see what it would feel like and if it would tell me anything about the way I read. I wanted to know if Roth was a writer it was even possible to get a general sense of, by dipping my toes into a few supposedly exemplary novels. So, I didn’t read 31 books. I read eight.

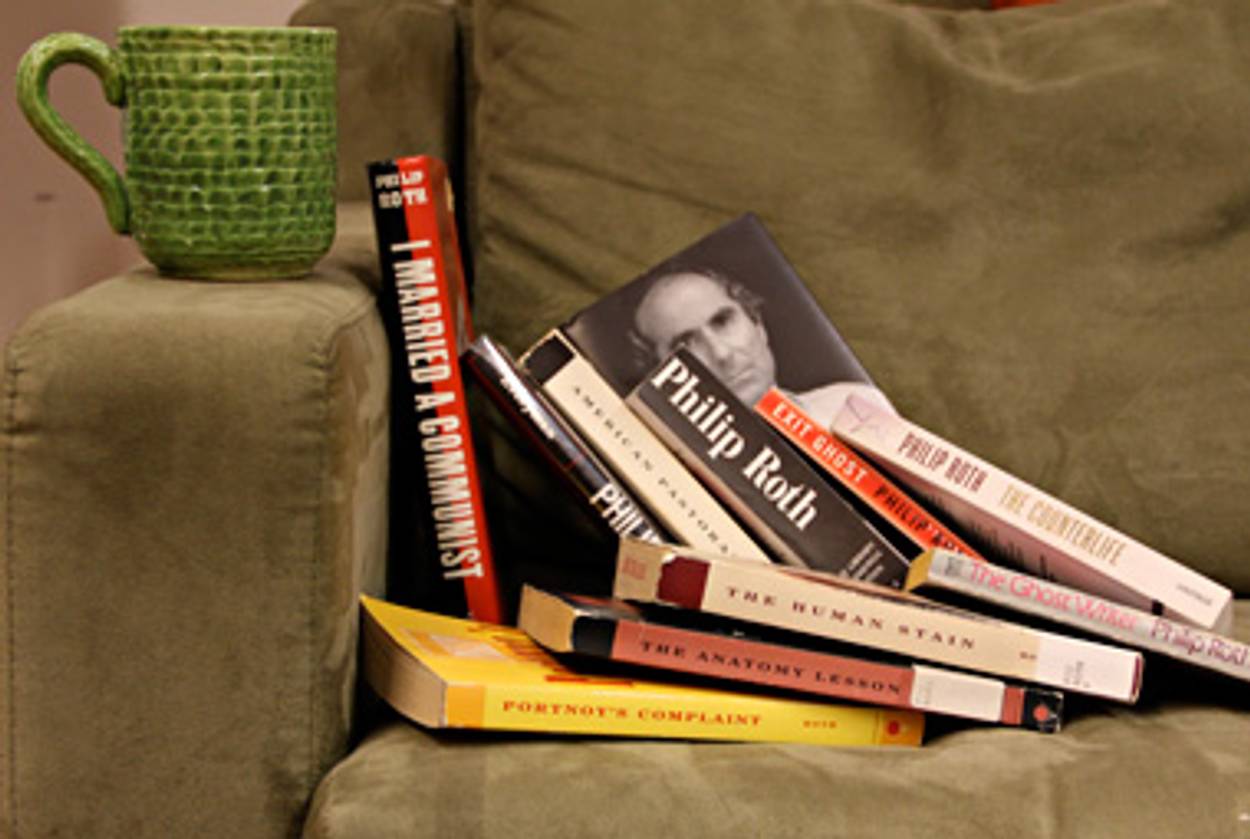

The way I chose those books was far from scientific, based on casual suggestions and availability as much as the specifics of Roth’s bibliography. His first book, Goodbye, Columbus (1959),was an obvious choice, and as the novel that made him famous (and both exalted and reviled), so was Portnoy’s Complaint (1969). Someone told me they thought I’d like The Counterlife (1986), which seemed as good a tip as any, and I took home The Plot Against America (2004) both because I’d heard great things about it, and because it was already at the library instead of needing to be transferred in. I added Everyman (2006) to my pile for the same reason (and also because it was nice and slim when compared to most of the others, as well as relatively recent), and The Breast (1972) because, well, it’s about a man who turns into a giant boob. I knew I wanted to read American Pastoral (1997) because it won Roth the Pulitzer Prize, and Patrimony (1991) because I figured a memoir would offer a different angle on the author. Skipping around seemed legitimate, since I wasn’t trying to understand Roth’s evolution as a writer in any kind of comprehensive way, but to see what came of ploughing through a stack of his books in a concentrated amount of time.

Even if I wasn’t sure what I would actually find in these hundreds of pages, I knew what I was supposed to find. The promotional copy on many of the books was comically over the top: It seemed like each one was hailed as Roth’s greatest triumph, the one boasting his most indelible characters, the rawest emotion and deepest cultural relevance, and the author glared out from his photo as if daring anyone to contradict the superlatives. The aura of undisputed greatness triggered competing impulses in me: On one hand, it’s reassuring to read books that have already been vetted and generally agreed to be excellent. Another part of me, though, was annoyed that adoring Roth should be a foregone conclusion.

Portnoy’s Complaint, I realized just a few pages in, is a book you really need to immerse yourself in—it should be read in as few sittings as possible. With very few section breaks and a careening narrative (the whole thing is truly a relentless, exhausting complaint), the best strategy is to get into the groove of Alex Portnoy’s voice and let it pull you along. And with little to hang on to in the way of structure, it’s the characters and small stories that stick: Alex’s account of his young cousin’s suicide, his ambivalence about his girlfriend (whose serious sex appeal can’t make up for what he thinks of as her unrepentant stupidity), another cousin who almost married a goy and then died in the war, the horror movie (and indelible, odious archetype) that is his mother. Portnoy’s life is one long, sickening Jewish joke; Roth is trying so hard to repel and frustrate us that reading becomes a sort of test of will.

I knew the book by reputation, of course, but the repulsive, repressive Jewishness at its core was still extreme enough to be jarring. It’s certainly to Roth’s credit that the book still shocks more than 40 years after it was published, especially considering that at a certain point, its literary value became inseparable from its cultural cachet. That’s the challenge of reading a book that’s become shorthand to such an extent that The Daily Show jokingly called it “the Jewish manual” on the same night I finished it. Somehow, though, Portnoy’s Complaint still stands on its own.

After that, reading The Plot Against America was a relatively soothing experience, and something of a stylistic shock. The historically complex novel is impeccably structured and straightforwardly told and makes Portnoy look like a sheer cathartic exercise in comparison. On a basic level, The Plot Against America is just a great read: It’s accessible and vivid and suspenseful along with being a smart, sly history lesson. Reading Roth’s alternative history of the period preceding America’s intervention in World War II and knowing this is not what happened to American Jews in the 1940’s (but could have, given some choice unfortunate events) makes you want to know more about what actually did. Something about tracing the divergence of history and fiction fixes the facts in your head better than the usual accounting of them and made me think the book would be an inspired way to teach anyone from high-school students to forgetful adults about the period. In a different way, Goodbye, Columbus also felt to me like it belonged on a syllabus, so much so that I was hearing reading comprehension questions in my head as I was reading: things like, why does Neil care so much about the kid in the library? Why does he insist that Brenda get a diaphragm? What does the title actually suggest? The Breast was similarly ripe for essay questions. It also just works: It’s short, funny, and disturbing, with the blend of comedy and pathos that defines absurdity.

I found The Counterlife harder to get lost in, though I know that’s part of the point of the book’s structure—its multiple “lives” and shifts in perspective are meant to be disorienting, each chapter set in a new time and place that forces a reader to start from square one each time. That idea appeals to me, as does Roth’s fascination (very much on display in these pages) with calling his readers’ attention to the way a story is constructed. Still, there was just so much speechifying here, so much yelling about who was right and wrong, and the stakes never engaged me.

But I thought American Pastoral, which also had some meta qualities (and which I was similarly primed to think was genius), was staggeringly good. I loved how Roth built the saga of his main character, Swede Levov, out of the memories of his own alter-ego, Nathan Zuckerman, so that Zuckerman’s personal reflections drive nearly the whole first quarter of the book, before the character smoothly shifts his attention to imagining the Swede’s story. In these layers of authorship and invention, it’s not just Roth writing the book, but Zuckerman building it out of his own memories and feelings about the past, fiction upon fiction. There’s a lot going on here—high-school sports, family tensions, political violence, sex, cattle-breeding, embattled optimism, blackmail, urban ruin, the bizarrely fascinating specifics of how to manufacture women’s dress gloves—but the entire book is riveting and deeply sad, revolving around lost dreams and ideals and an underlying question of “why me?” that one might call biblical if it didn’t instead resonate as distinctly, terribly American. It’s that rare novel that kept me reading long past the point when I planned to go to bed, and I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it since.

The day after I finished American Pastoral, I read Patrimony in three hours. Roth’s memoir of his elderly father’s decline was harrowing, lovely, and impossible to put down, its ending inevitable but the exact path to it heartbreakingly uncertain. Lucid and forlorn, he’s writing about the experience of memory here as much as he’s recounting specific ones, and they’re memories that actually belong to him, rather than ones he’s ascribing to his various fictional stand-ins. After reading so much that represented a meeting of his life and fiction, the Roth who is writing here seemed strikingly exposed. There’s nothing sexy or glorified, just shit smeared all over the walls and a son tasked with cleaning up the mess.

This felt like a reasonable, tidy way to conclude my reading spree. But Everyman—the first of Roth’s recent cycle of short novels—was still sitting at the top of the pile next to my coffee table, taunting me with its brevity.

For all its slimness, Everyman struck me as one of the bleakest books I’d ever read. It’s not merely depressing, but insistently, painfully grim. The book is a fairly concise chronicle of an aging man consumed by his mistakes, and it makes growing old sound like the hardest, loneliest, and most desperate situation a person can be in, to the point where it seems to have been written from a place of utter fear and despair. A few of the plot points were drawn directly from the pages of Patrimony: the severe heart trouble Roth recognized just in time to save his life, how he made a wrong turn on the way to visit his father and ended up at the crumbling cemetery where his mother was buried. In Patrimony,Roth writes that while that accidental detour offered him no comfort, it nonetheless left him satisfied because it felt “narratively right.” It was an apt way to describe the broader relationship between his life and work, and it was strangely gratifying to see so clearly how he’d translated that particular experience into fiction—15 years after he described it in a memoir.

Everyman left me so despondent that I worried it would color my feelings about Roth’s other books. But that might have happened had I finished with any of the others, too (albeit with a different aftertaste). And in the end, my Philip Roth binge made it hard for me to think of any one of his books as an individual work. Read together, they left behind a web of allusions and cross-references and authorial obsessions and outbursts and reflections that I’m happy to leave all tangled together in my head, letting the Nathan Zuckerman of American Pastoral touch base with his younger self from The Counterlife, having Swede Levov explain his familial knowledge of glove-making to the nameless protagonist of Everyman (who himself has some expertise in the fine jewelry trade), and letting Alex Portnoy and Goodbye, Columbus’Neil Klugman swap stories—while all the female romantic interests get together to compare their own notes on this group of tortured Jewish men. Read on a bender like this, the connections between stories and characters and themes all but broadcast themselves, and I got a better sense of the man behind them than I would have had I read American Pastoral by itself, in installments the length of a subway ride.

We read, I think, to confirm things we assumed, as well as to be surprised by what we didn’t know. And timing matters. All of us remember books we’ve read at the wrong point in our lives—too soon, or too late—or in a moment that felt almost overwhelmingly perfect. There are books whose specifics drifted away soon after we finished the last page and others that we think about often, for reasons we don’t always understand. Maybe if I’d read different books by Roth, or the same ones in a different situation, my opinion of them would be less favorable. Maybe if I added just one more book to the stack, I would have gotten too sick of him to have anything positive to say.

Or maybe not. Discovering Philip Roth this way was totally unnatural, but it felt totally right. And, hey—now I’ve read Philip Roth.

Eryn Loeb, a contributing editor for Tablet Magazine, is a freelance writer and editor in New York.

Eryn Loeb, a contributing editor for Tablet Magazine, is a freelance writer and editor in New York.