Secret Crypto-Jewish Diaries Rediscovered in New York, Displayed in Mexico City

Ahead of Mexico’s Independence Day, the autobiographical writings of Inquisition victim Luis de Carvajal finally go home

After renouncing Judaism, Luis de Carvajal was granted mercy: Instead of being burned alive, he was tied to a pole, noose around his neck, and slowly asphyxiated to death. His body was consumed in a massive fire organized in a public plaza in 1596 at a Mexico City auto-da-fé, in which his sister and mother also died.

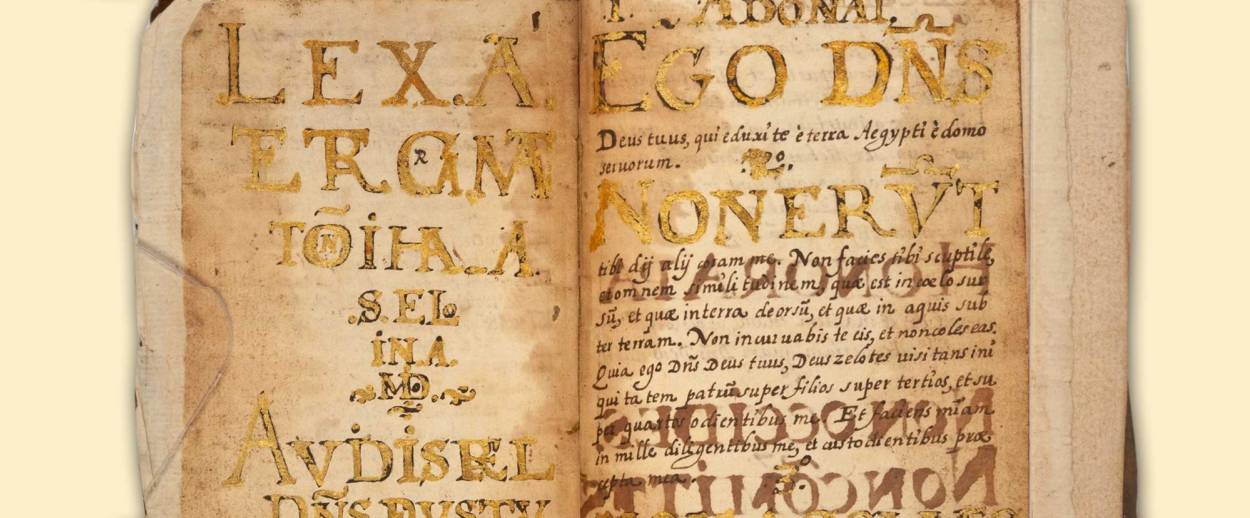

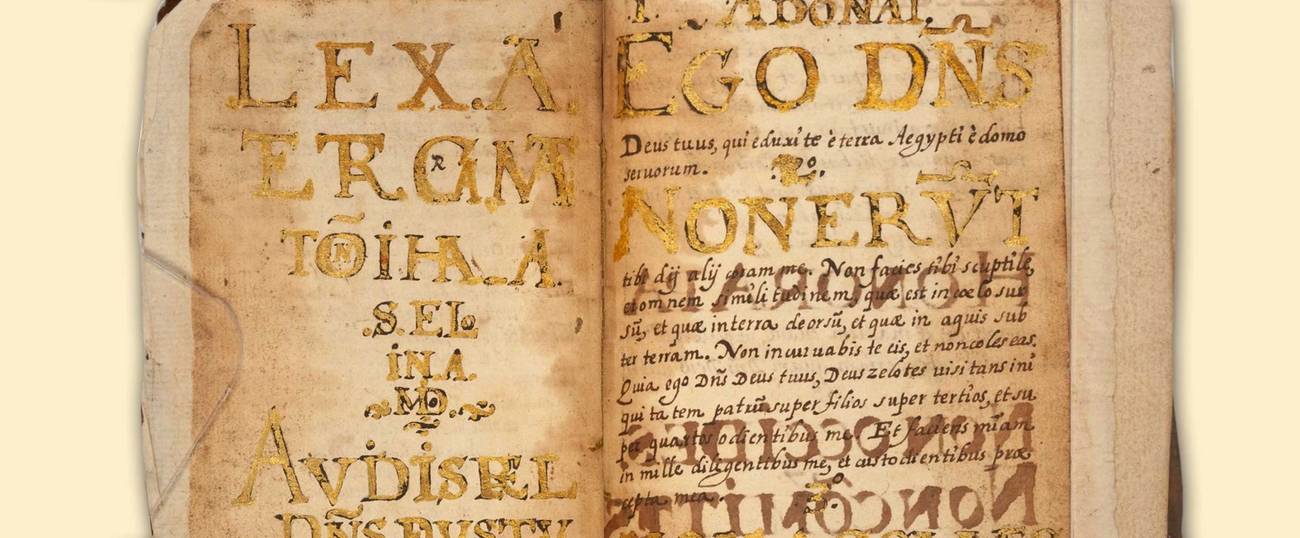

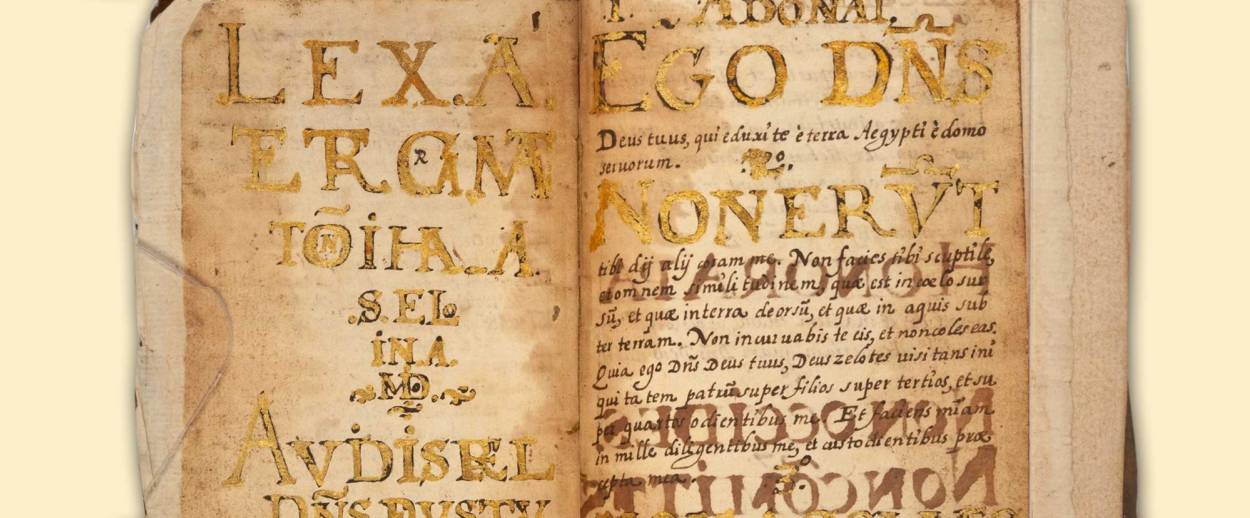

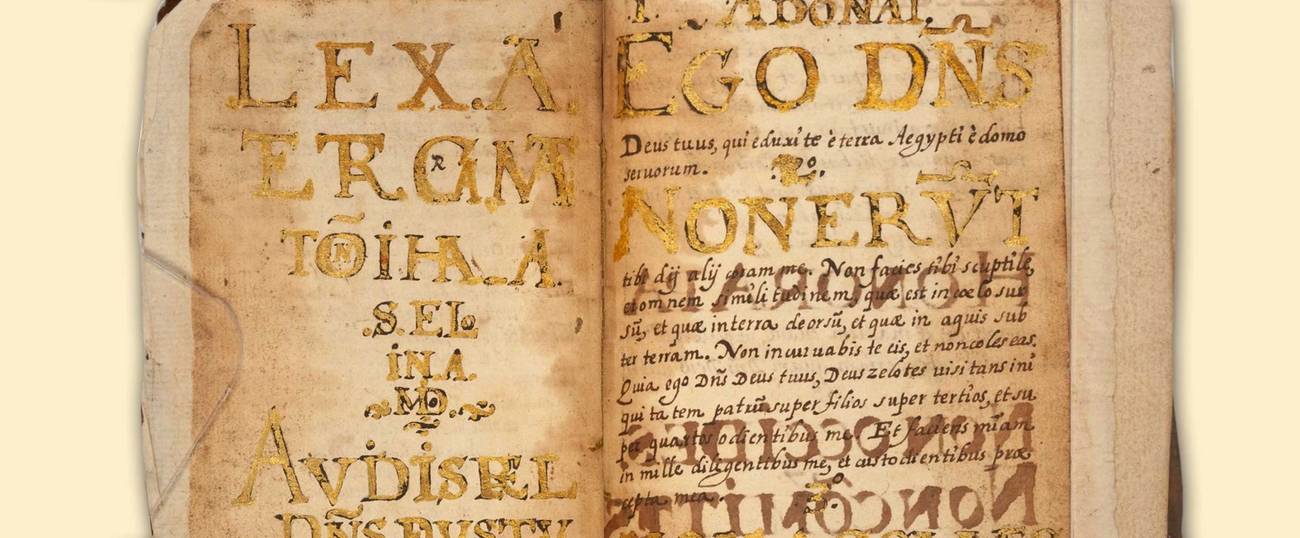

During the trial, a collection of manuscripts in Carvajal’s distinctive calligraphy was used as proof of the family’s Crypto-Jewish practice. Found beneath Carvajal’s hat and behind a wall in his house, they consisted of a book of psalms titled Lex Adonai, a guidebook to prayer and an autobiography written in the third person, under the name of Joseph Lumbroso (Joseph, the Enlightened). The documents were later stored in the Inquisitorial Archives and, eventually became part of the Inquisition Collection in Mexico’s National Archives.

Then, in 1932, they disappeared from sight.

In 2016, though, Leonard Milberg, a wealthy collector of Judaica, recognized them at an auction of Swann Galleries, in New York and contacted the Mexican government, which in turn confirmed the document’s authenticity and negotiated its return.

Now, the oldest documents attesting to Jewish life in the New World are back in Mexico, offering a fascinating window into what it was like to live as a Jew in a newly founded Spanish colony.

***

Born in 1567 in Benavente, a small Spanish town close to the Portuguese border, Luis de Carvajal made the perilous trans-Atlantic journey to Mexico as a child. His family sailed with his uncle, Luis de Carvajal El Viejo (the Elder), who was a decorated Conquistador and, at the time, charged by Felipe II to become governor of Nuevo León, a frontier land in the north of Mexico.

One Yom Kippur close to his 13th birthday, Carvajal’s mother let him in on a secret: His family was not Catholic; as a matter of fact, they covertly followed the Law of Moses. The revelation was nothing short from traumatic; the Inquisition had been active in the Spanish colony since 1572 and the practice of heretic religions was not only outlawed, it was punishable by death.

Other Crypto-Jews, however, helped Carvajal make sense of his spiritual path. When he got sick he was taken care of by a certain Dr. Luis Morales, who enlightened his family on the nature of Kashrut laws and the ways of the Shabbat. Carvajal was an avid student of the Old Testament and discussed its teachings with his mother and sister. And although he followed each law with tremendous passion, Carvajal soon realized that if he wanted to be part of the “chosen people” he had to undergo tremendous pain. He had to be circumcised. In a devastating part of his autobiography, Carvajal chronicles how, in a state of religious euphoria, he stood under a palm tree next to a river and performed his own bris with a pair of worn-out scissors.

His life is full of examples of intense religious zeal, which deepened as he matured. Eventually, though, the family was outed to the Santo Oficio by a political competitor of his uncle. Carvajal the Elder, who was a fervent Catholic, denied all the charges. But his nephew—on trial for the first time, in 1589—confessed his adherence to Mosaic Law and promised to reform.

But this was also a charade, according to the autobiography: In the prison cell, Carvajal experienced vivid dreams of King Solomon pouring him a delicious, nourishing liquor; once out, he became convinced that those visions had been offered to him by the Jewish God. Overtaken by religious passion, he began writing minuscule notebooks under the name of Joseph the Enlightened, in reference to the biblical character of whom he thought he was a sort of reincarnation.

The thin 4×3-inch notebooks were to be sent to his brothers, who were living in religious freedom in Italy—and were meant to be read by the wider Jewish world, so they could attest to his miraculous life. Carvajal was aware of the danger: he hid these tiny manuscripts close to his chest, taking them out only in important Jewish festivities so that his mother and sister—also pardoned in that first trial—could use them to pray.

While most of the Crypto-Jews who wrote about their experience with Judaism did so only after they had escaped to freedom in Italy, or Holland, Carvajal’s autobiography is unique having been written within the Iberian world. “To write down one’s Judaizing exploits while still within the grasp of the Inquisitors was an extremely dangerous and unwise decision,” notes Yeshiva University professor Ronnie Perelis, who has studied Carvajal’s life for 15 years.

When Carvajal was caught by the Inquisition the second time, there was no turning back. For over a year, the family was subject to horrific torture; Carvajal himself ended up denouncing 120 other secretly practicing Jews and, according to some accounts of the trail, renouncing his faith, getting on his hands and knees and praying for mercy.

***

In 1932, a Yiddish professor by the name of Jacabo Nachbin requested access to the Carvajal manuscripts, located at the National Archives. Nachbin was a celebrity in the Yiddish press of Argentina and Brazil and the father of Leopoldo Nachbin, who would become Brazil’s most important mathematician. He arrived from Germany at some point after World War I and was the first Jewish historian to examine the history of the Jewish communities in Brazil.

Before setting out to Mexico he had been a teacher at Northwestern University in Illinois and what is now New Mexico State University, in Las Cruces. In Mexico, he was doing research on Jewish communities and teaching at the National University.

Given his credentials, none suspected any ulterior motive for consulting the archive. As a matter of fact, he was granted permission because Dr. Puig, minister of education at the time, interceded on his behalf. But an archivist soon realized that some of the file was missing. Eventually, Nachbin was arrested, though not in possession of the manuscripts.

The heist was a major event, covered by the country’s main newspapers. According to some of the accounts of the trial, Nachbin strongly denied the charges, saying that he was being scapegoated for being a foreigner; he had studied countless similar documents before, he said, and had never been charged with stealing.

Three months after being imprisoned, Nachbin was acquitted, thanks, in part, to the lobbying of the Brazilian ambassador, but also because no one found any incriminating evidence on him. Immediately after his release he took a plane to the United States and resided there until he was kicked out for being illegally married; he was last seen in Paris, in 1938, and is thought to have perished in the Holocaust.

Alfonso Toro, who transcribed Carvajal’s autobiographical manuscript before it was stolen, was convinced of Nachbin’s guilt. Toro’s charge is full of anti-Semitic tropes: In his book, La Familia Carvajal, he goes as far as to state that the Yiddish scholar wanted to steal the documents because he thought Carvajal was a martyr for his tribe. Toro’s accusations are so vociferous that some scholars even suspect Toro of playing a role in the heist.

The most convincing proof of Nachbin’s guilt, though, was the fact that some of the missing documents actually came back from the United States, arriving via return mail to the post office located right across from the National Archives. One package was sent to a Mr. Lang in New York, who never showed to pick it up: Among other things, it contained an avocado seed with diminutive letters inscribed on it with a needle by Carvajal, who used the fruit to secretly communicate with his sister during prison.

Regardless of who was responsible; the manuscripts were considered lost.

Then, in July 2016, a wealthy and avid collector of Judaica named Leonard Milberg phoned the Mexican consulate in New York demanding to speak to the consul concerning a matter of the utmost importance. Consul Diego Gomez Pickering met Milberg in his office on the 12th floor of a building located between Grand Central Terminal and Park Avenue: Milberg gave the consul a 40-minute crash-course on Crypto-Judaism and explained to him the importance of Carvajal.

Milberg had seen the documents, he told the consul. They were being auctioned, in the city, by Swann Galleries. With this in mind, Pickering set in motion his diplomatic machinery to establish whether the manuscript was the real thing and, if so, to bring it back to Mexico. Balthazar Garcia, a specialist in old documents and codes and director of the Mexican National Library of Anthropology and History flew to New York to authenticate the pieces.

“These old manuscripts,” he told me during an interview, “are not made of paper, like today’s notebooks. They are actually made of beaten cloth.” At the time, Garcia ran a chemical examination of the ink, looking for traces of the iron and almond nutshells that served to give the ink its black hue. Oxidation in the ink attests to the documents’ age; in this case certifying that these were 400-year-old manuscripts in almost-perfect condition.

The ultimate proof of authenticity came through handwriting analysis. Carvajal, an extraordinary calligrapher, was actually employed as one when he was released from his first trial. After comparing the manuscripts’ handwriting with other examples of Carvajal’s correspondence with his family, Balthazar concluded that they had been written by the same man.

With the authenticity issue out of the way, Milberg came to an agreement with Swann Galleries and bought the manuscripts for a reduced price. He then donated them to the Mexican government, under the condition that they first be displayed at the New York Historical Society, where they formed part of The First Jewish Americans, an exhibit that ran last winter. In Mexico, the manuscripts were exhibited for a very short period at the Museum of Memory and Tolerance, in a rather paltry, dark display, uncomfortably situated next to a room about the killing fields of 1970s Cambodia. Eventually, after being digitized online, the manuscripts were restored to the National Archives, completing a 450-year journey of faith.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Alan Grabinsky is a freelance writer and journalist based in Mexico City, covering Jewish life and urban issues for international media.