The Dagger of Faith in the Digital Age

A vitriolic medieval manuscript illuminates how Google is destroying the act of reading

I have come to my favorite café (which has very fast Wi-Fi) and ordered a coffee. Sitting in my favorite sunny window, holding my hot mug and watching ephemeral wisps of steam flicker and disappear over the coffee’s surface, I open my laptop (a MacBook Pro with a 750 GB hard drive—enough to store over 300 million pages of text or over 100 billion words) and I enter a three-word search in Google. Looking at the results (delivered in less than a second by one of Google’s estimated one and a half million worldwide servers, which process over 4 billion individual searches per day, including mine), I follow the first link, and I am off to Coimbra, Portugal, where there is an extraordinary multilingual manuscript (MS 720) that has, so far, been little studied.

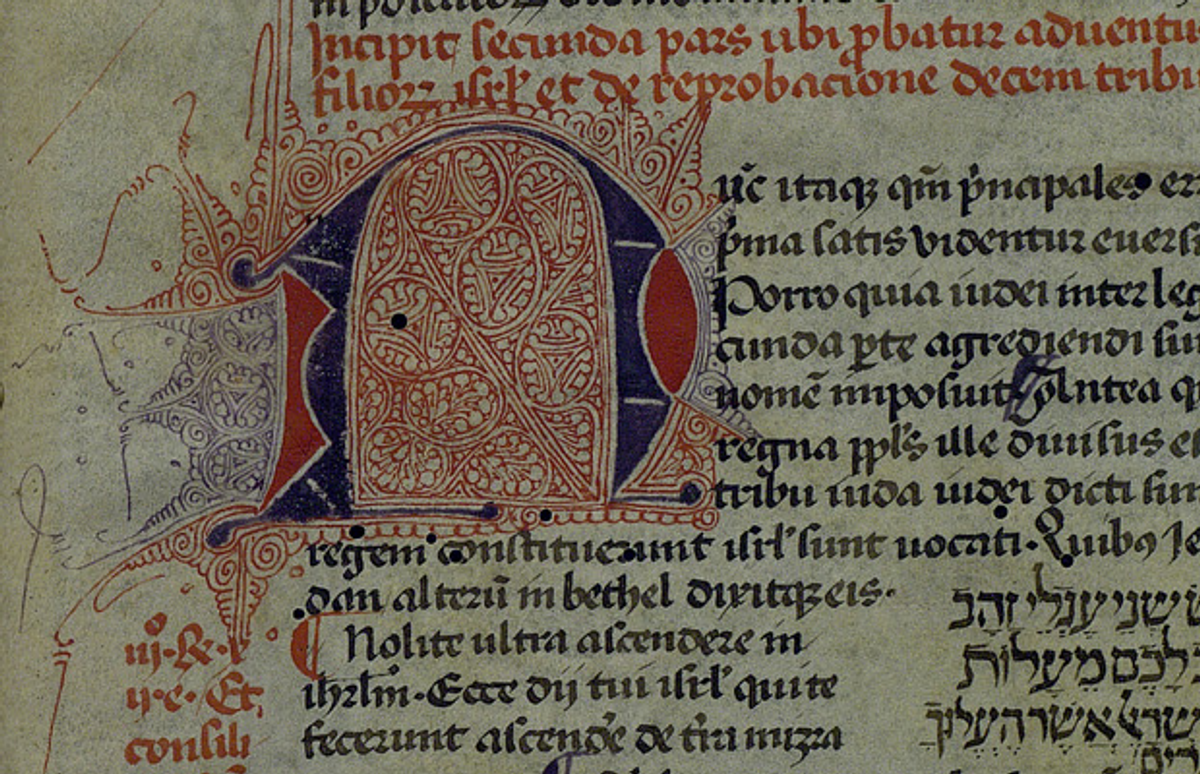

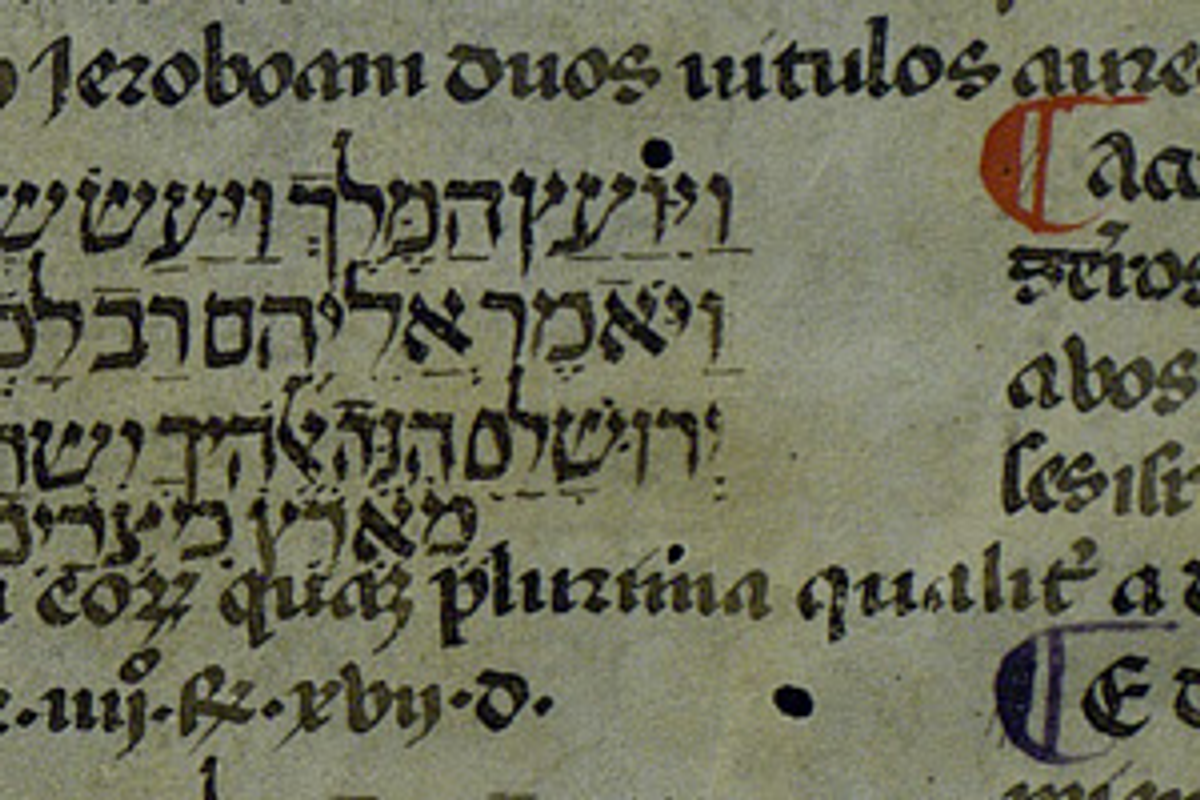

With two more clicks I am viewing it in high resolution: one of 13 known copies or fragments of the 13th-century Christian polemic Pugio fidei (“Dagger of Faith”), finished by the Catalan Dominican Ramon Martí in 1278. The work is a lengthy, three-part treatise that aims to prove Christian truths on the basis of biblical and post-biblical texts (Talmudic, Midrashic, Qur’anic, and philosophical). Unsavory in its vitriol, it is nevertheless striking for its inclusion of citations in the original languages (mostly Hebrew but also Aramaic and, in a few instances, Arabic) alongside careful translations into Latin.

Like most of the manuscripts of the Dagger, the Coimbra codex, datable roughly to the late 14th or early 15th century, is incomplete, containing only the second and third parts of the work and lacking the first. It is, however, one of a handful of copies that actually contain non-Latin text, many having omitted it or copied it only partly. Most scholarship on the Dagger has been done on the basis of the two 17th-century printed editions (Paris, 1651, and Leipzig, 1687), both of which are composites of four similarly incomplete manuscripts, now lost. Recently, more attention has been given to the oldest and most complete manuscript (and probably an autograph copy), now held in Paris (Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève MS 1405), the only one to contain all the text in all languages. While scholars of the Dagger are generally aware of the Coimbra manuscript, virtually no studies have been done on it in particular. Perhaps this is, I surmise as I sip my coffee, because Coimbra lies somewhat apart from other major manuscript collections in the Iberian Peninsula in Madrid and Lisbon. On my screen (15 inches, with a Retina display of 5.1 million pixels), I open one browser window with the Coimbra manuscript and another next to it with the searchable text of the 1687 edition, one of some 30 million works in 480 languages that have been scanned by Google Books so far.

Coimbra does lie at a distance from Madrid and Lisbon, but this limitation was partly overcome in early 2009 when the Coimbra library put this high-resolution scan of the whole manuscript online, providing free, open access to a codex that had previously lain in relative obscurity. Now anyone like myself with an Internet connection can instantly see an image of the manuscript, as well as quickly find out information about the text, the author, and the other manuscripts that survive. The manuscript may be housed in Coimbra, but its intellectual home is no longer there. Along with millions of other documents and images, it has been untethered from its place, “removed,” as John Berger has stated about reproduced art images, “from any preserve.”

I am part of a team of scholars preparing the first modern edition of the work, and today I begin by comparing the text in Coimbra to those of the Paris manuscript and of the printed editions, searching for variants. My eyes dart from window to window, I zoom in and out, I search for text and my data accumulates steadily. For a few minutes, I am able to concentrate and work effectively. But soon my mind starts to wander. I am interrupted by daydreams of Coimbra, of what it is like to sit at the library there. I imagine the animal whose skin was made into parchment, the medieval scribes who copied this text—hands aching, eyes straining, working at their desks in a fading light. I become aware of my own comfort—my painless hands, my leisurely labor—and the tools that enable my work begin to annoy me. I stop working and begin to ponder my own discontent.

The Coimbra manuscript, viewed on my laptop in my favorite café, is a perfect starting point to explore the meaning of manuscripts in an Internet age. The questions it raises have led me to consider the significance of two major innovations that were introduced only a few years ago but that I believe have produced a sea change in the nature of reading and writing, a change akin in its revolutionary character to the invention of the metal type mold and printing press: the rise of book digitization through efforts by Google Books, Project Gutenberg, the Perseus Project, the Hathi Trust, and others; and the dramatic evolution not only in the portability, speed, and scale of computing devices, but in their capacity to search for and retrieve data copiously and quickly. Studying the Coimbra manuscript has also pressed me to explain how and why, in the context of the digitization, manuscripts have acquired for me a heightened value as “authentic” objects, unique products of human labor that are largely untranslatable to the codified languages of digital text.

It is not my intention simply to bemoan the loss of the bygone days of printed books or handwritten codices, or to wistfully elegize the pleasure that I, like many, feel from direct contact with manuscripts (but not from screen reading), although I will indulge in little bemoaning and elegizing. My point has to do with the status of manuscripts in the context of our new capabilities of text searching and portability. Certainly, digitization and searchability have had an effect similar to that produced by earlier reproductions of the image, that of encouraging the fetishization of the original, and I confess now that my feelings toward manuscripts are beginning to approach something like fetishism. I have begun to feel this even more strongly because comprehensive searchability has introduced a rupture into my relationship with the book. This rupture, characterized by a radical inversion of the traditional hierarchy of power between me and the text and a radical magnification of the scale on which we interact, is not the kind of rupture produced before among readers by earlier advances in the technology of writing or reproduction (the invention of the codex, the printing press, the photograph, or even of the early Internet). It is a rupture produced by my new power to extract words and information from a text without being subject to its order, scale, or authority.

***

The fact that the Coimbra copy of the Dagger of Faith has received little scholarly attention is not a serious critical problem. The Coimbra codex is of interest to those studying the copying and circulation of the work, and it is also one of the more attractive manuscripts of the Dagger, neatly composed and carefully copied and including large initials with red and blue flourishes. Such facts, however, are only weakly compelling for those interested in the text itself, which is far better represented by the Sainte-Geneviève manuscript in Paris and far more accessible in the Leipzig edition (also reprinted in a 1967 facsimile, which I photocopied as a student and used until Google put the Leipzig edition online for free viewing and searching). The Coimbra manuscript, however, does contain at least one very significant detail not found in any other copy of the Dagger, a detail that has escaped scholarly notice entirely. It is not surprising that this detail has been overlooked, because it is actually not there—it is a lack, an empty space that quietly runs throughout the manuscript’s over 300 folios. This lack is a missing third column, running next to two full columns of text given in vocalized Hebrew and Latin translation.

What was supposed to fill this blank space? The answer can be found on the first two folios, where the third column contains the beginning of a text that was to continue through the rest of the manuscript but was never finished—a Castilian translation of the work’s thousands of biblical passages cited in Hebrew and translated into Latin. These passages in the first folios are from 1 Kings 12.28 and 2 Kings 17.16-20, both about how the Israelites “forsook all the commands of the Lord their God and made for themselves two idols.” They are only a taste of what was supposed to be a new Romance translation of the Bible cited throughout the Coimbra manuscript but that never actually came to be. In its place, this void runs for hundreds of folios and signals, albeit by its absence, one of the defining features of medieval textuality: It is, in Paul Zumthor’s definition, “fundamentally unstable,” constituting “not a fixed shape of firm boundaries but a constantly shifting nimbus.”

On the screen, the manuscript does not look essentially different from how it looks in its home library. None of the main text (copied in a neat Gothic Rotunda hand) has been cut off by the frame of the image, and only a few of the marginal comments or details are obscured. But although the digital image of the text is not incomplete, its presence on the screen is not the same as when the codex lies open on the table.

***

“In principle,” Walter Benjamin reminds us, “the work of art has always been reproducible.” And what is this electronic image except a new and more efficient means of reproduction? Considered in this light, the digitization of the Coimbra manuscript is nothing more than an enhanced facsimile. Coimbra’s digital Dagger is simply a photographic reproduction, and any photographic reproduction of any manuscript would have a similar effect of “freezing” the object and transforming it into a free image unlinked to its source.

Detached from its library, detached from its medieval past, it escapes from any necessary context, becoming, to return to Berger’s words, “ephemeral, ubiquitous, insubstantial, available, valueless, free.” The manuscript folio, prepared by hand from the skin of an animal killed by hand, and its script, written by hand with an instrument fashioned by hand and with an ink mixed by hand from materials gathered by hand, is transformed into a set of pixels, points of light corresponding to numbers specified within a machine’s code. This code’s series of “digits” (so-named, of course, after the digits of the hand, our first counting tool)—vast streams of zeros and ones—produces a picture of a manuscript, and it would seem that both the image and the object depicted constitute more than the sum of their parts. But are the two interchangeable?

Considering this code as simply another kind of media, one might think that nothing has substantially changed from Benjamin’s time to the present, from the invention of lithography to streaming video. Yet part of the Internet’s revolution, as many have pointed out, has come only in the latter part of the 1990s with the rise of search engines and especially the invention of Google’s uniquely effective page-rank searching algorithm. In a 2004 opinion piece, Hamish McRae pronounced with confidence that, “the development of search engines is one of those classic events that changes the world.” The ability to perform targeted and accurate retrieval very quickly changed not only the scale of the technology of reproduction and communication but also the nature of each user’s interaction with information. Rather than floating adrift on a sea of data, the individual user was given the power to navigate and control his or her course of action. The scale of the change was exponential because it potentiated a simultaneous expansion in the amount of available data and a dramatic improvement in the ability of every user to retrieve and even alter that data.

Taken separately, these changes would not necessarily signify a turning point, but together the simultaneous magnification of scale and control has deeply altered our relationship to facts and their meaning. Such changes have transformed the nature of media and communication, influencing politics and the economy significantly and even altering the experience of space and time for many people. This revolution is first and foremost a breakthrough in data management, and data management is an expression of power—power over privacy, knowledge, the interpretation of history, and even over the perception of truth itself.

This revolution might be explained in terms that cognitive neuroscientist Merlin Donald has used to describe one of the key developments of modern human culture, the rise of external memory or “external symbolic storage” (writing, shared symbolic systems, the creation of monuments with inscriptions, etc.). Donald argues that this transition was the foundation of the shift from a “mythic” structure of knowledge to a “theoretic” structure, one capable of reflecting upon itself. Donald links the rise of computer technology and digital storage to this process in the evolution of consciousness: What first had been an advance—through shared externalization—in the nature of memory is followed now by an advance in the way human thought can interact with that external memory. Larger data-storage capabilities are akin to “brains” with more memory capacity, and faster data retrieval is akin to faster and more efficient recollection. External storage in the form of electronic memory, which long ago surpassed the scale of human memory, is now coupled with a retrieval technology that surpasses the speed of human thought.

In the wake of the advent of Google’s probing search engine, the most significant effect of the revolution in data accessibility, in the humanities at least, is the digitization of text. We can get a sense of the nature of the change by considering a telling anecdote told by Jonathan Rosen in his The Talmud and the Internet, published in 2000. Rosen tells of his quest for the source of a quotation from John Donne that he vaguely remembered but could not trace. “I finally turned to the Web,” he quaintly writes, but “my Internet search was no more successful than my library search. I had thought that summoning books from the vasty deep was a matter of a few keystrokes, but when I visited the Web site of the Yale library, I found that most of its books do not yet exist as computer text. I’d somehow believed the world had grown digital, and though I’d long feared and even derided this notion, I now found how disappointed and frustrated I was that it hadn’t happened.”

It has, of course, now happened, on an ever-expanding scale, one more vast than Rosen in the year 2000, or Neil Postman or Sven Birkerts a decade earlier could probably have foreseen. Although the economic and legal significance of this change is not fully evident, I see digitization of text as the most radical change in the humanities ushered in by recent digital technology, much more radical than the changes in convenience, scale, or even the proliferation of new media. Its truly revolutionary character lies in the way searching has changed the nature of reading and of books.

The digitization of text obviously has many positive effects. Every scholar who works with digital sources has had the experience of finding more of what he or she wants from a text more quickly and efficiently through keyword searches. As Steven Levy states: “Just as Google had changed the world by making the most obscure items on the web spring up instantly for those who needed them, it could do the same with books. A user could instantly access a unique fact, a one-of-a-kind insight, or a breathtaking passage otherwise buried in the stacks of some dusty book in a distant library. Research tasks that had formerly taken months could be completed between breakfast and lunch.”

Jean-Noël Jeanneney, former head of the Bibliothèque nationale of France, argued in his Google and the Myth of Universal Knowledge that “the enemy is clear: massive amounts of disorganized information. The progress of civilization can be defined, among other things, as the reduction of the forces of chance in favor of thinking that is enriched by organized knowledge.” The searchability of books would seem on the surface to provide the ultimate reduction in such hostile forces and the ultimate consolidation of power against them.

The control that this consolidation of power brings with it has been welcomed by many but not universally hailed by all as positive. In 2005, only one year after McRae declared that Google had “changed the world” and Google first unveiled its book-digitization project, historian David A. Bell in his article “The Bookless Future” began to muse about the “dangers” of text searching:

Reading in this strategic, targeted manner can feel empowering. Instead of surrendering to the organizing logic of the book you are reading, you can approach it with your own questions and glean precisely what you want from it. You are the master, not some dead author. And this is precisely where the greatest dangers lie, because when reading, you should not be the master. Information is not knowledge, searching is not reading; and surrendering to the organizing logic of a book is, after all, the way one learns.

In Google Books, the reader no longer approaches a text as a learner, but as a consumer, one who dictates what one finds and who will choose an alternative if what one finds does not immediately satisfy. Christine Rosen, responding to Bell, has aptly described such reading as a new kind of skimming, a surface reading akin to “panning for gold.” Readers who read searchable text do not “dig deeply … most merely sift through the silty top layers, grab what is shiny and close at hand, and declare themselves rich.”

This superficial skimming (or targeted diving) can produce quick but narrow results by reducing the number of uncontrollable variables. Such a reduction can be a very good thing—few would complain about being able to work faster and more efficiently—but the effect that this can have on understanding is often unexpectedly blinkering. To view the text according to parameters defined by precise and limiting search terms is not simply to see only a fraction of the whole. (When, in fact, have we ever seen anything but a fraction of the whole?) Rather, as all text is transformed into data, the categories by which meaning is sifted and interpreted become narrower and more rigid. This changes the experience of the reader by limiting a priori the possible results, turning all books into reference books. The effects produced by this divide between reading and searching are impoverishing. David Levy already lamented in 2001, “We are now so oriented toward information-seeking and use that we have increasingly become blind to other, equally important dimensions of reading.”

This may sound like a familiar, reactionary complaint: Ever since (as Plato tells us in Phaedrus) Thamus, the Egyptian king, criticized the god Theuth (Hermes) for inventing writing and numbers, arguing that it would ruin our memories and deprive us of understanding, people have responded to technology by prophesying the decline of wisdom. Nicholas Carr points out in his critical evaluation of the advent of Google, “the arrival of Gutenberg’s printing press, in the 15th century, set off another round of teeth gnashing,” offering examples of those who bemoaned the rise of printing and its deleterious effects on reading in a manuscript culture. None is more explicit than Benedictine Abbot Johannes Trithemius (d. 1516), who urged his fellow monks in his De laude scriptorum to preserve the vocation of copying manuscripts by hand despite the advent of printing. Trithemius emphasized the fundamental difference between manuscripts and books, seeing the former as more durable and more stable.

Reflecting on the fact that Trithemius did not scorn the power of the press to disseminate his own ideas, printing them in 1494, communications scholar Clay Shirky sees “an instructive hypocrisy,” namely that “a professional often becomes a gatekeeper, by providing a necessary or desirable social function but also by controlling that function.” My goal here is not to deny the usefulness of digital media, nor to seek control over the habits of readers, nor to join the choir of voices claiming that technology is doing harm to our attention span (though, in the interest of full disclosure, I may agree that it is). Rather, I wish to suggest that just as books were defined by comparing them to manuscripts, so the value of manuscripts—as sources, as objects, as symbols—can be reimagined and their uses rearticulated as books change.

Moreover, my quarrel here is not with screen reading per se, but with the specter of searchability that lurks behind it. To read strategically, via text searching, one does not need to wade through any unsought surrounding terrain, and in fact one is less and less able or allowed to do so. Such control represents a significant inversion of power in our experience of reading, a shift that librarians have come to refer to as a loss in “serendipity.” The reductive reading of a digital world, one in which text has become mechanically searchable, is a reading mediated principally through data. In an obvious way, this encourages a superficial engagement with writing and its significance, one directed at primary meaning rather than secondary or implied meaning, and one guided necessarily by selectiveness rather than completeness and by preconceived logical categories rather than creative intuitions developed at the moment of reading. The ossification of the categories of textual meaning necessarily eliminates the free and creative association characteristic of human thought, and yet it is such association that for me yields the intellectual benefits and the aesthetic pleasure of reading. Technology can produce larger and more elaborate data sets, but it cannot mimic the tangled and unexpected byways of insight and intuition.

By avoiding the unexpected and unplanned—which are aspects of the very essence of manuscripts—the Internet search and even the simple digital reproduction likewise obscure the reality of the manuscript as a handmade object irreducible to any single dimension. In the Coimbra manuscript of the Dagger, any skimming will likely overlook the glaring empty column, so full of suggestive potential but invisible to a reader approaching the text only in a targeted way. I confess that, for the first two years that the Coimbra manuscript was available in digital form, I viewed it only rarely, relying more on the searchable printed edition from 1687. When I did consult it, I jumped from section to section according to my search results drawn from the online text. It was not until I stumbled literally by chance across the first folios in which the third column was filled with a Castilian translation that I “saw” the emptiness I had previously overlooked in my focus on keywords. Attempting to read the text through the lens of Google’s searchable code of ones and zeros, I could not perceive the manuscript’s singular and meaningful lack.

***

This experience has given me pause and made me reflect on how and why I work. In our brave new world of power searching, text-as-data, and ultra-portability, the manuscript has come to acquire a new significance for me, one different from its meaning only 10 years ago. Manuscripts provide me with a way of reflecting on the possibilities of such reading that are easy to forget in our world of data. They help me remember that the nature of medieval manuscript culture was not based on information or even texts per se, but on engagement with symbols, engagement that always took place on a scale in which the reader was never fully the master of a text. The virtue of the manuscript for me is that, no matter how minutely reproduced in image or dissected and ordered in code, no matter how searchable its text, it exists apart and before and always larger than such renditions. What is exceptional about it is not immediately recognizable in its shape or color, as an iconic image might be, maintaining its recognizability across an endless stream of reproduction. Rather, the manuscript is sui generis in its unpredictable mix of word and image and scar. Because of this living variance, manuscripts have become bastions of an intuitive human sense of knowing and thinking that I see as under threat in a world of readily available information.

Manuscripts also help me understand more precisely what is really happening with the advent of Google Books that did not happen with Gutenberg: an inversion in power between reader and text. As books were originally designed to be reproductions of manuscripts (witness the layout and lettering of most incunables), they were also invested with some of the same qualities that were valued in medieval reading: Texts were repositories of wisdom, partners in dialogue, links in a sacred chain of authoritative tradition. I do not believe that publishing destroyed the capacity for readers to engage deeply and personally—whether on a spiritual, ethical, rational, emotional, or aesthetic level—with these aspects of texts. In this sense, my complaint is rather different from that of Trithemius in his praise of scribes. The printed book may have represented, as a mass-produced text, a great reduction of the polyvalent presence of the manuscript, but it still contained an obscure product made on a human scale that had to be engaged with in order to be used. Printing increased the power to disseminate and reproduce texts and images just as the early Internet did, but it did not provide a magic bullet for extracting the secrets that those elements held. Now that books can be penetrated and manipulated more thoroughly—indeed, with a power and speed unprecedented in the history of human language—those rare qualities have been stripped away. In Google’s hands, the book has been sliced open, its inner parts exposed, and I believe that it is in danger of dying as its organs are harvested for profit.

At the same time, I also feel that a greater burden has been placed upon the reader by such rough treatment. Though readers have complained at least since the birth of printing about drowning in too much text, they faced the proliferation of books—even to the dawn of the 21st century—with no expectation to be able to master such material. Now, however, books are suddenly at our fingertips, though our eyes can go no faster than before. Moreover, the mountains of words are more menacing because we now have the tools to work with them, the drills to mine them, without the mind to comprehend their depths. Greater storage may be like a bigger brain, and faster retrieval a better memory, but neither can produce critical reflection, and we are left with something like savant syndrome—a prodigious power of recall that far outpaces our ability to think. By our ability to measure and exploit them, books become large and impersonal, more like the silent infinite spaces of the universe that terrified Pascal than the harmonious musical spheres that enchanted Kepler.

It is for this reason that I have started to love manuscripts even more. By preserving the unmeasurable as a condition of understanding and of meaning, they are becoming less “useful” in a pragmatic sense. As books yield their content more readily, manuscripts are more valuable to me precisely because they are irreducible to their usable parts. Their shifting and chaotic natures, their lack of regularity, their imperfection—these human things now seem to be even more valuable as testimonies of the nature of medieval reading. Manuscripts embody the ephemeral, the unfinished, the damaged, that which is lost for whatever reason of fate or chance or any other force beyond codification. As seen from our new common vantage point on history, one that is both more penetrating and more narrow, manuscripts have acquired for me a new presence, a new aura.

This new significance consists of the fact that it embodies a kind of irreducible idiosyncrasy that is virtually impenetrable with the tools of targeted reading. The manuscript cannot only be seen—it must be touched, smelled, read, received, interpreted in order to be appreciated and understood. It can be appreciated fully only by means of a give-and-take relationship, and in that relationship it will always remain partly elusive. Any reproduction, including even the most detailed digital rendering, is able to preserve only a vestige of the manuscript’s real, dynamic nature. Like a deep-sea creature that perishes and decomposes when forced up to the light and low pressure of the sea’s surface, the manuscript exists on its own terms, in its native habitat, in a world in which the reader is not in full control and has only limited understanding.

***

Fifteen years ago, when the Internet was a captivating new toy, many believed it would provide the freedom and scope that the critical edition, in its linear empiricism and ordered sobriety, lacked. Ever since Charles Faulhaber predicted that “the decisive change between the current practice of textual criticism and that of the 21st century will be the use of the computer to produce machine-readable critical editions,” the bibliography on digital text editing has grown steadily and is now very large. Best-known among such discussions is Bernard Cerquiglini’s 1989 Éloge de la variante (translated as In Praise of the Variant), which he ended with a paean to digital text: “The computer, through its dialogic and multidimensional screen, simulates the endless and joyful mobility of medieval writing as it restores to its reader the astounding faculty of memory.” Because, as Cerquiglini oddly believed, “computer inscription is variance,” he also claimed that it best represents medieval manuscripts in a way never attained or attainable by the critical print edition. Faulhaber’s prophecy has indeed started to come true, and digital text has begun to acquire the status of a righter of wrongs perpetrated on medieval manuscripts by the printed book. As Francesco Stella noted in the collection Digital Philology and Medieval Texts, “The manuscript offered the reader a plurality of levels of meaning and a capacity for interactive enjoyment, for disassembly and reassembly of the text that printing took away from us and that, however, computerized apparatuses can restore.”

I believe not. As Neil Postman reminds us, technological change is not cumulative but is a “Faustian bargain” in which something must be sacrificed in order for something new to be gained. The disequilibrium in power between reader and text that has arisen in a world of searchable books, in which the former may use and abuse the latter without being subject to its logic or limitations in any way, undermines “interactive enjoyment” and “plurality” and replaces these with dominance and singularity. This new kind of reading does not open a dialogue (or even a competition) with the text—it simply discounts authorial voice or scribal interpretation altogether, replacing both with a readerly will to power over data. Of course, medieval readers were themselves masters at exerting their own power over texts, even those by the most classical authors. As John Dagenais notes, “Medieval readers read piecemeal, in patches, like scavengers combing out master text for what they can use. They are self-centered, greedy, disrespectful. They are reductive.” However, the reductive reading of medieval readers, whether of fragments and florilegia or of “authorial” texts, was not essentially different from that of all reading before the advent of text searching because it was undertaken on a human scale in which the reader’s advantage was not at all certain and understanding was bounded on all sides by the ineluctable horizon of the unknown.

One might counter that the work of encoding manuscripts for online consultation (such as that of TEI, the Text Encoding Initiative) is indeed slow and careful work, and one would be right. But such encoding is only slow for the encoder, and encoded text can subsequently be exploited with great speed and efficiency, be read only according to the categories provided by someone else. This was, in a way, always the function of printed editions, and the best an online edition can provide through its non-linear, interactive, hyperlinked structure is a more elaborate critical edition, one in which the lists of variants and the critical apparatus have not been replaced by something better or truer, but only made more convenient to use and more economical to represent. Such editions operate under the same illusion of all critical editions—that of being able to approach medieval presence more directly through more information and more analysis. A digital edition pursues these illusions with more urgency than does a print edition and obscures its intentions with even more efficiency.

Just as Google Books does not simply strive to augment the reading of a book but to actually replace the reader’s book with the searcher’s book, so the ultimate goal of digital editions and digital facsimiles, I believe, is not only to reflect the “original,” to “capture” or “recapture” it, but to effectively replace it with a better image of itself. Whereas philology, the study of language history through texts, creates (like fetishism) a “desire for presence,” digital philology creates a simulacrum or iconic replacement for this presence. The injunction from Kings against graven images rings in my ears, and I choose a fetishism of the frail human object over an idolatry of the power of the machine.

It is no surprise that the missing third column has been universally overlooked in the Coimbra codex of the Dagger of Faith, because even as it speaks on so many levels of its circumstance and intended meaning and unrepeatable history, it is, in its digital avatar, obscured by the overwhelming presence of its simulacrum. In viewing it from the comfort of a local café, on my own time, at my preferred screen resolution, I am grateful for its accessibility and convenience and I can work more effectively because of it. I am, however, also wary of the dangers it brings, above all the danger of my own complacency before it. I am wary lest I forget that the gleaming digital image of the Coimbra manuscript’s missing third column is a sort of enchanted mirror that ironically reflects back the impossibility of reproduction, of reflection, of control, of total understanding—ironically some of the very things that Ramon Martí seems to have been coveting in his polemical attacks on Judaism like the Dagger. Yet if we can keep the eyes to see it, the manuscript’s lack leaps out as a stark reminder that reading is an imperfect and imperfectable activity whose final lesson is its own inscrutability, for it bespeaks the inscrutability of all that is time-bound—of history, of fate, of loss—should I say it?—of death. Umberto Eco has stated, “With a book…you are obliged to accept the laws of Fate, and to realize that you cannot change Destiny…In order to be free persons we also need to learn this lesson about Life and Death.” In the age of book searching, however, in which books are now the fodder of a few key strokes and the flitting caprice of an impatient mind, it may now be the inviolate manuscript that can, as never before, best teach us this law of Necessity.

***

I close my laptop and open a book to read, one of what Google estimates to be 129,864,880 individual books ever published in the world, which it aims to have digitized within ten years. If each book were 70,000 words long—about 150 pages—that would amount to around nine trillion searchable words. I begin to read some of those words but am distracted as I notice the person sitting at the next table send a 140-character tweet on Twitter, one of an average of 500 million such Tweets now being sent each day. At an average rate of 12 words per Tweet (or 6 billion words a day), I muse, doing the calculation on my phone, more words will be Tweeted within the next four years than can be found in all books ever published put together, and they will also be searchable. (Twitter claims to service over a billion searches of past tweets each day).

I return to my book. As I read, one sentence reminds me of another from an earlier chapter, and my mind lights up with a sense of a connection, although I cannot remember precisely what I am reminded of. I feel a subdued giddiness as I—thinking across some unknown, tangled stretch of my brain’s quadrillion (one thousand million million) neural synapses—start to comprehend a structure to the text, but my clarity is like that in a dream, certain at one moment but fleeting and beyond articulation. I flip back in search of this connection, this ephemeral key to the text’s larger meaning. I search for a over a minute, skimming text, flipping forward and back, but I cannot find what I think I remember. The insight slips from the frame of my mind’s eye as smoothly as it entered it. My neural channels go dim. I look at the page and pause, straining to think of the insight I lost.

Feeling vaguely unsatisfied, I sip the last of my cold coffee as the sun begins to glow orange through the café window, a final, full incandescence before sinking to dusk. (If the Solar System is some four billion years old, my wandering mind begins to think, this amounts to the—I calculate again—trillionth odd sunset visible from earth, although human eyes like mine have witnessed only a small fraction of all these). The book’s pages weigh heavily in my hand, and my eyes are drawn to a doodle of a cloud raining into a beer mug, drawn in the margin by another reader’s wandering mind. Feeling my empty stomach growl, I look into my own empty mug and I hear myself sigh as I stare at the few stray grounds left in the bottom of the cup.

And then, in an instant, I don’t look through it but at it. As I see the mug’s emptiness, I remember the manuscript’s empty third column, and my mind leaps, and I understand: we can study, dissect, codify, enumerate, reproduce, simulate, and idolize the data presented by the text, but we can, in the end, only contemplate its lack. The thought pours over me and stays, forefront in my mind, like an epiphany: ironically, it is that lack, that irreducible unknown, that proves to be the richest object for the gradual and measured work of reading because it is the most unfathomable, but also somehow, the most familiar. Amazingly, beautifully, it is also the most real, the most human, the most present.

An earlier version of this essay appeared in Digital Philology 3:1 (2014). It was written as part of the collaborative project “Legacy of Sepharad: The Material and Intellectual Production of Late Medieval Sephardic Judaism,” led by Javier del Barco and sponsored by The Spanish State Plan for Scientific and Technical Research and Innovation.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Ryan Szpiech is a professor at the University of Michigan, where he studies the literatures and cultures of medieval Iberia. He is the author of Conversion and Narrative: Reading and Religious Authority in Medieval Polemic.