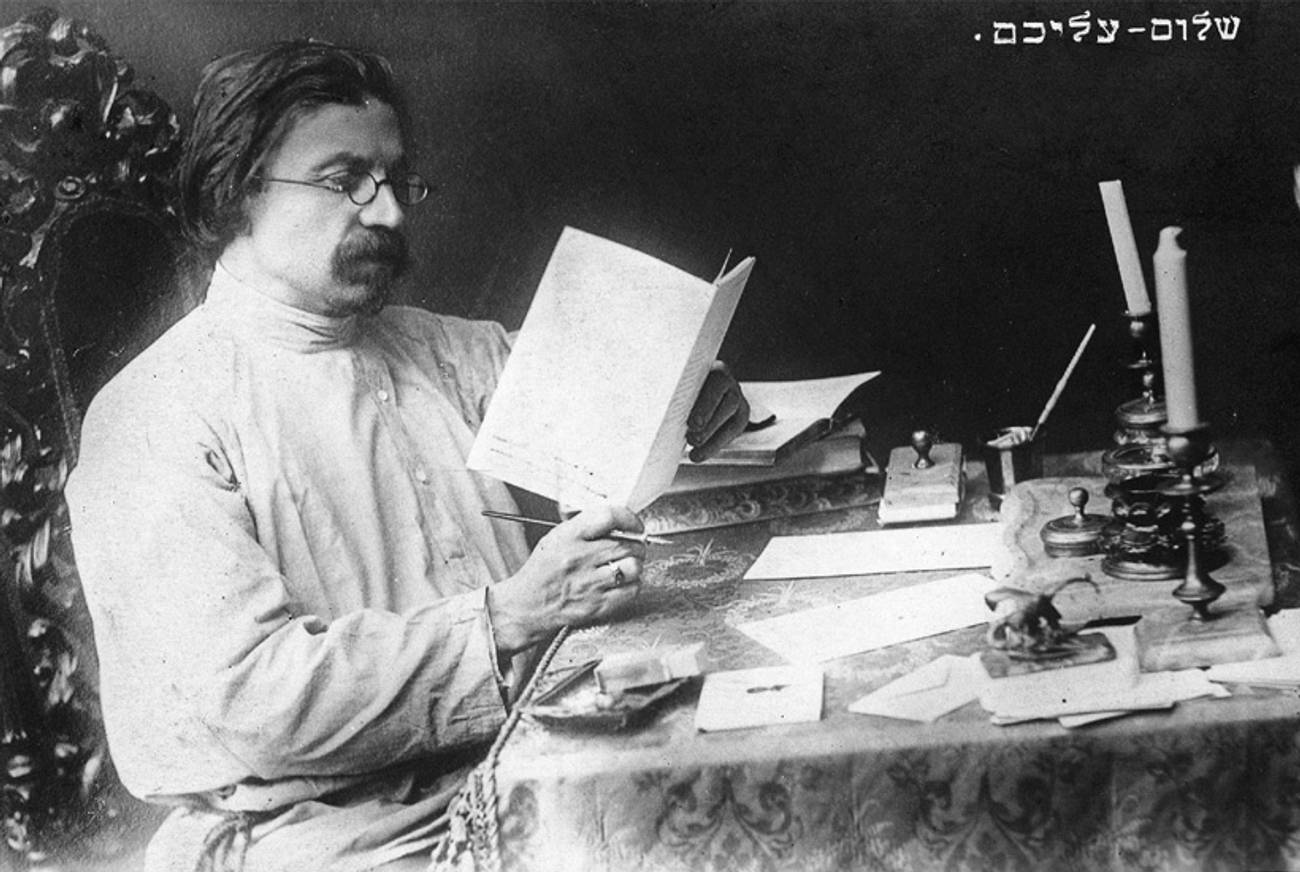

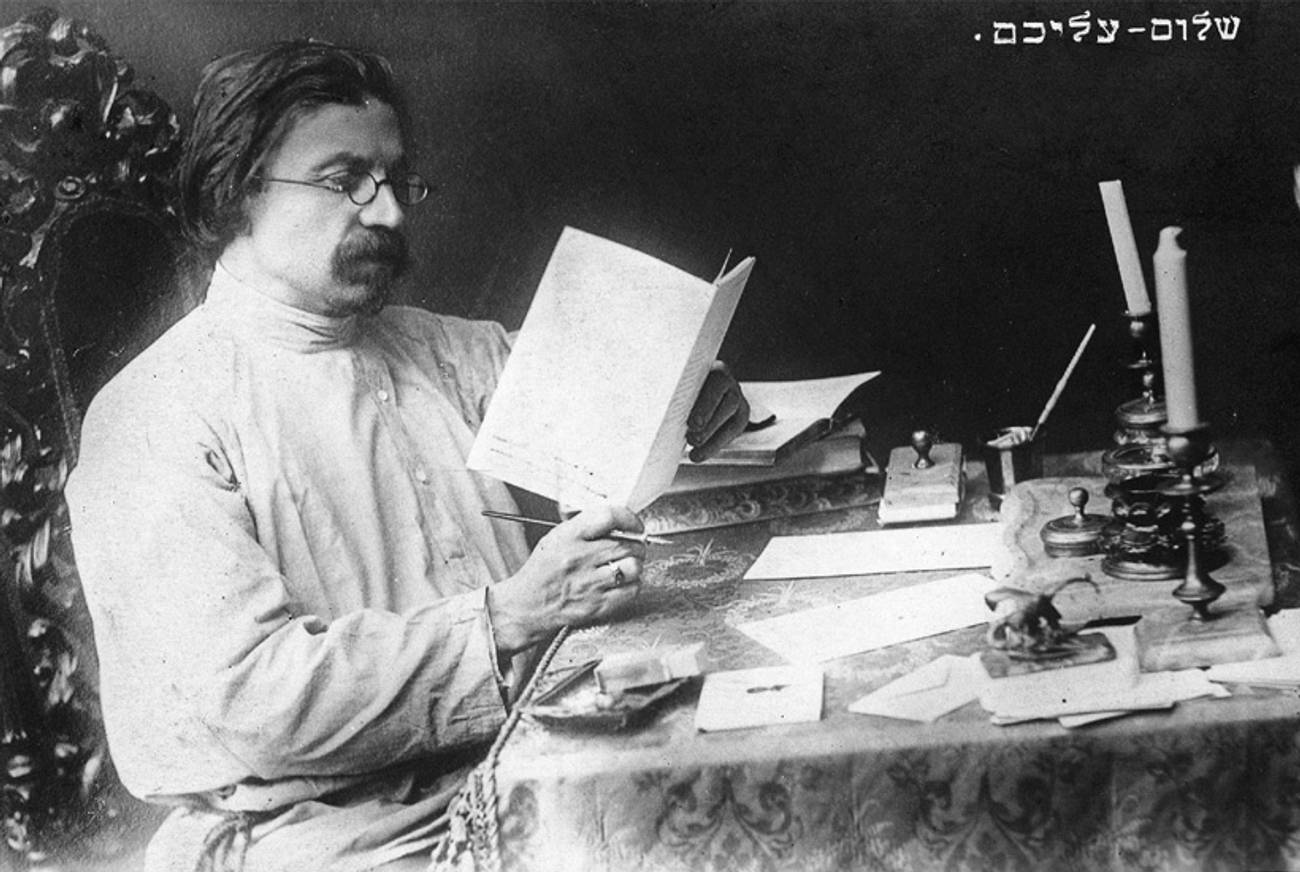

Sholem Aleichem Created Tevye—and the Modern American Jewish Sense of Tradition

In an excerpt from Nextbook Press’s new biography, the Yiddish master’s funeral at Carnegie Hall begins to shape a legacy

In his new biography The Worlds of Sholem Aleichem, Jeremy Dauber recounts the extraordinary life and career of the man who was dubbed “the Jewish Mark Twain,” a writer who created Tevye—the enduring character at the center of Fiddler on the Roof. Sholem Aleichem’s reputation continued to grow after his death in 1916, as Dauber describes in the following excerpt.

Arrangements had to be made.

It would have to be a public funeral, there was no doubt of that; and the Lower East Side had seen its share of those. Both respected figures like the Yiddish newspaper publisher Kasriel Sarasohn and the Yiddish playwright Jacob Gordin and less respected ones like the Jewish gang leader Jack Zelig had been accompanied to their eternal rest by crowds and spectacle. (And at least once, during the funeral of the Orthodox rabbi Jacob Joseph in 1902, by a riot; an outbreak of violence that started when workers tossed bits of iron out of factory windows at procession members led to two hundred riot police “slashing this way and that with their sticks…shoving roughly against men and women alike.”) But the question transcended simple logistics and security: How do you bury, in the words of one of his eulogists, “the Jewish people in microcosm”?

First, the family decided, you needed an arrangements committee, and they asked Judah Magnes, the head of the New York Kehillah, to head it up. Though the Kehillah didn’t always succeed at its stated goal of unifying New York’s Jewish communal affairs, Magnes was still probably one of the few individuals who could draw together the multitudinous constituencies bridged by Sholem Aleichem’s appeal. Some backstage political struggles notwithstanding, Magnes and the rest of the committee—all friends or associates of Sholem Aleichem’s, as well as committed Zioinists—would produce a smashing success, a national pageant.

The committee’s first decision was to invite over a hundred Yiddish writers to watch over the body in fourteen consecutive three-hour sessions as it lay in state for two days at 968 Kelly Street. Twenty-five thousand people, alerted by black-bordered extra editions of the Yiddish papers, stood in lines stretching for blocks waiting to pay their respects. That Monday, May 15, 1916, three Pereyaslav landsmen, Jews from his hometown, purified and prepared the body. Everything was done strictly according to tradition, though few if any of the writers were traditional—a fitting tribute to Sholem Aleichem, whose own behavior was less traditional than his sensibility.

At 9 a.m., ten prominent Yiddish writers bore the coffin to the hearse; as they exited the house, the cantor of the Reform Bronx Montefiore Congregation sang the “El malei rakhamim,” the traditional funeral prayer. Other Yiddish writers headed a vast procession, twenty thousand strong; the writers were accompanied by over a hundred psalm-reciting children from the Orthodox Talmud Torah and the National Radical School, strange bedfellows united by the author’s appeal. The procession’s first stop was at Ohab Tzedek, the Orthodox synagogue on Harlem’s 116th Street. There, “El malei rakhamim” was chanted again, this time by the synagogue’s world-famous cantor, and Sholem Aleichem’s friend, Yossele Rosenblatt. Crossing the Harlem River, the procession lost some members, but gained them back and more as it traveled south down Fifth, then Madison Avenue. It stopped at the Kehillah’s offices at the United Hebrew Charities Building, on Twenty-first Street and Second Avenue, where it was met by members of the Yiddish Writers and Newspaper Guild. They had assembled at the Forward Building (whose windows, like those of other offices of the Yiddish press, were draped in black) and had marched northward, four abreast, up Second Avenue to join the cortege.

Rosenblatt conducted a brief memorial service at the Charities building, and the procession continued south, to the heart of the Lower East Side. Six mounted policemen cleared the way, and two hundred officers managed the crowds: Inspector O’Brien had learned from the riot fourteen years ago to provide an adequate police presence. Opposite the headquarters of the Hebrew Actors’ Union, a company of actors, led by Jacob Adler, joined the procession. (They had paid their respects more concretely Saturday night, when the Yiddish theaters had shuttered for the evening in the departed author’s honor.) Then it stopped once again, at the Educational Alliance, where the main memorial service took place. Police struggled to hold back the crowds: only six hundred ticket holders were admitted into the building. The coffin was ushered into the auditorium, where the dignitaries waiting on the podium, from Jacob Schiff to Chaim Zhitlovski, made up a who’s who of Jewish New York. Magnes read the crowd Sholem Aleichem’s will, which the author had asked to be published on the day of his death.

After the service, the procession continued south, stopping for another brief service at the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, where Rosenblatt recited “El malei rakhamim” once more, then crossed the Williamsburg Bridge and wended through Brooklyn to Mt. Nebo Cemetery in Cypress Hills. Sholem Aleichem’s surviving son, Numa, recited kaddish at the grave; the Yiddish writers Sholem Asch and Avrom Reyzen spoke, as did the socialist poet Morris Winchevsky and the Zionist leader Nachman Syrkin, among others. Thousands stood there, in the bad weather, listening patiently.

Those thousands at the cemetery were a small percentage of the throngs who lined the streets of the Bronx, Manhattan, and Brooklyn and watched from fire escapes and rooftops. Estimates for the total number of participants vary wildly, ranging from 30,000 to 250,000; the actual number was probably somewhere between 150,000 and 200,000. This out of a population of about 1.5 million Jews in New York City—and about 6 million New Yorkers overall. Sholem Aleichem’s audience—like the details of his funeral, like his work, like himself—contained vastnesses.

And that audience, thanks in no small part to the circumstances of the funeral, was spreading fast, and perhaps more widely and to more unlikely precincts than Sholem Aleichem might have expected. The floor of the United States House of Representatives, for example, where, after a discussion of savings-and-loan and agricultural banking bills, a member of the New York Republican delegation, William Stiles Bennett, spoke of “the greatest spontaneous gathering of the people in the history of our city,” 120,000 people, “toilers, men and women alike, who could ill afford the loss, [who] sacrificed the day’s wage to join in the tribute” to “a man whose very name is unfamiliar.” Bennett credited his fellow representative Isaac Siegel, a New York lawyer who’d made his way up through the public schools to rise high in the Republican hierarchy, for alerting him to Sholem Aleichem’s reputation. That reputation, according to Bennett, was not only for his “humorous stories with a kindly cast,” but for the “trenchant pen…in behalf of those in public life whom he cared for.”

Bennett’s evaluation was certainly inspired, at least in part, by a document he asked to be read into the record: Sholem Aleichem’s will, which the family had released to the public following the funeral service. Bennett had also entered into the record a New York Times editorial that breathlessly began with the thought that “in the whole great domain of testamentary literature, it would be hard to find a will better deserving to be viewed as a ‘human document’ in the full sense of that term” than “that of the man whose least apposite title was ‘the Jewish Mark Twain.’” Both were probably struck—as was a news reporter who covered the will’s release for the Times—less by the details of the disposition of his estate than by the larger social and ethical questions it posed.

The Times titled its story “Aleichem Begs to Lie with Poor: Will of Noted Writer Says His Ambition Is to Rest Among Plain Jewish Laborers,” struck, apparently, by the will’s first clause, which reads, in full: “Wherever I die I want to be placed not among aristocrats, or among the powerful, but among plain Jewish laborers, among the people itself, so that the gravestone that is to be placed upon my grave should illumine the simple graves about me, and these simple graves should adorn my gravestone, even as the plain, good people during my lifetime illumined their Folkschreiber.” The editorial, by contrast, singled out the will’s tenth and final clause for praise, in which Sholem Aleichem begged his children and successors “to protect mamma, to beautify her old age, to make her bitter life sweet, to heal her broken heart; not to weep after me, on the contrary, to think of me with joy; and the main thing—to live together in peace, to bear no hatred for one another, to help one another in bad times, to remember one another upon occasion in the family, to have pity on a poor man, and when circumstances permit, to pay my debts, should I have any. Children! Carry with honor my hard-earned Jewish name, and may God in heaven come to your help. Amen!”

In his remarks, Bennett told the story of the loss of a huge fortune of an oldest son, but added that “no tinge of bitterness crept into his writings…[and the] shining radiance of his affection turned his falling tears into a rainbow of promise.” At the time of Sholem Aleichem’s death, very little of his work had appeared in English; and so for much of the American audience—certainly the English-speaking, non-Jewish audience—their first meeting with Sholem Aleichem was because of a funeral and through a will. It was an encounter with a ghost who claimed, in his testament, to be of the people and to be their own writer, and who asked to turn sadness into joy, almost, in so many words, to turn tears into laughter; and an introduction to the writer as family man, thinking of his children and expressing, from beyond the grave, his overwhelming husbandly love. Following the tone set by Jewish leaders and intellectuals, the non-Jewish world was crafting their image of Sholem Aleichem as, to use some other adjectives Bennett employed, hopeful, sincere, humble, and joyful.

Not all of this, as we now know, was an entirely accurate depiction of the facts.

Carnegie Hall was draped in black.

It was the thirtieth day after Sholem Aleichem’s death—his shloyshim, in traditional Jewish parlance—and twenty-five hundred people crowded into Carnegie Hall to pay tribute. The writer had stipulated in his will that a percentage of the family’s income from the sale of his works be donated to a fund for needy Hebrew and Yiddish writers, and the Sholem Aleichem People’s Fund would be the beneficiary of the memorial evening. (The cheaper seats went for a dime; eventually, demand dictated that the pricier ones be opened to the general public as well.) From the darkened stage, Sholem Aleichem’s portrait looked out at the audience from behind a row of distinguished speakers.

“Let my name be mentioned by them with laughter rather than not be mentioned at all,” the author dictated from beyond the grave, and the evening self-consciously attempted to emulate that sensibility of turning mourning into merriment. A lugubrious recitation of a mourner’s prayer by Yossele Rosenblatt and his choir early on notwithstanding, the noted Yiddish writer Sholem Asch—famous throughout the Yiddish world for his scandalous play God of Vengeance, soon to become a best-selling English writer—chided the audience that “we are taking his death too sadly…he was an apostle of joy, and it was his wish that we be joyful. If all the world were like Sholem Aleichem, there would be no sadness.” And as the great figures of modern Yiddish literature in America—Asch, the playwright Dovid Pinski, the humorist Moyshe Nadir, the poet Avrom Reyzen—read from Sholem Aleichem’s work, laughter rolled through the cavernous hall.

In his opening remarks, Judah Magnes reminded the audience of the deceased author’s testamentary with that, as he wrote, “the best monument for me will be if my works are read and if there be found among the better-to-do classes of our people Maecenases who will publish and distribute my works in Yiddish”—or, as the will specified, “in other languages.” Everyone knew the will also suggested that, in lieu of saying the mourner’s kaddish if his family was unable or unwilling, absolution would be granted if “they all come…and read this my will, and also select one of my stories, one of the really joyous ones, and read it aloud in whatever language they understand best.” Literature was the new generation’s religion; and, looking to posterity, Sholem Aleichem took care to accommodate not only changes in faith but changes in language, as he saw his children, and grandchildren, moving away from the Yiddish his world was composed in and of.

He had lived to see his work published widely in Russian translation, among other languages. English, however, with some few exceptions, had seen little of Sholem Aleichem between hard covers. But the translations of those early years, like the early memorial service, continued the process of creating a very particular version of his persona, and of his legacy.

His first appearance in English came courtesy of an unusual Englishwoman.

*

Helena Frank was the granddaughter of the Marquis of Westminster; her father, a Christian convert, would open his house to Sholem Aleichem when he was visiting London. (Sholem Aleichem suggested that she embodied “the transmigrated soul of Mother Rachel,” Hannah, or Queen Esther; “a noble tender Jewish soul in a Christian body.”) Her 1912 anthology Yiddish Tales is a sampler of work by various authors; though Sholem Aleichem is only represented by five examples, Frank’s introduction would help set the tone for reading Sholem Aleichem (along with Yiddish literature in general) in English. Describing the tales as each having “its special echo from that strangely fascinating world so often quoted, so little understood…a world in the passing, but whose more precious elements, shining, for all those who care to see them, through every page of these unpretending tales…will surely live on,” she has them fall somewhere between symbolic keys and cultural curiosities rather than works of literature—presenting Eastern European Jewish life as a vanishing world decades before the outbreak of the Second World War.

And the trend would continue. Hannah Berman, a Dubliner who had received copies of Sholem Aleichem’s newspaper serials straight from the source, had translated Stempenyu in 10913 in London; seven years later, she published a translation of Sholem Aleichem’s stories with Knopf called Jewish Children. The New York Times, covering the book’s publication, linked the stories directly to the author’s posthumous celebrity: “Shalom Aleichem, the ‘Jewish Mark Twain,’ whose ‘Jewish Children’ has just been published by Alfred A. Knopf, is perhaps the best loved writer of his race. Thousands upon thousands of Jews mourned at his funeral, which was held in New York several years ago.” Choosing children’s stories certainly made sense: as we saw, Sholem Aleichem himself had chosen that segment of his oeuvre to present to a non-Jewish reading public. And Knopf tried to stir up crossover appeal by getting Dorothy Canfield Fisher, an early advocate of the Montessori movement in America and herself a prominent contemporary author of children’s books, to write the introduction. And here’s her argument for reading Sholem Aleichem:

“Like many Americans (probably the majority),” she wrote, “I had more notions, blurred and inaccurate though they might be, about life in Thibet [sic] than about life among Jews.” She clarified, though, that she meant what in Woody Allen’s famous locution were called “real Jews”: “When I say ‘Jews’ I mean those who have not diluted the ancient traditions of their race and religion; not the East Side, partially Americanized Jew, nor the sophisticated, intensively cultivated cosmopolitans…But the people into whose hearts Sholom Aleichem bade me look were not only new to me, but richly dowered with an unbroken tradition complex and ancient beyond belief for an upstart Anglo-Saxon.”

What was valuable about Sholem Aleichem’s stories, particularly for non-Jewish readers? They showed non-Jews what real Jews were like. And what made an authentic Jew? Tradition.

Sholem Aleichem, whose genius came precisely from artfully delineating tradition’s reaction to modernity’s stress and strain, might have begged to differ.

This essay was excerpted and adapted from The Worlds of Sholem Aleichem, out today from Nextbook Press.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Jeremy Dauber is a professor of Yiddish literature at Columbia University, and the author of In the Demon’s Bedroom: Yiddish Literature and the Early Modern and Antonio’s Devils: Writers of the Jewish Enlightenment and the Birth of Modern Hebrew and Yiddish Literature.

Jeremy Dauber is a professor of Yiddish literature at Columbia University, and the author of In the Demon’s Bedroom: Yiddish Literature and the Early Modern and Antonio’s Devils: Writers of the Jewish Enlightenment and the Birth of Modern Hebrew and Yiddish Literature.