David Blaine Goes Up and Up and Up to Heaven

Can the great illusionist make suffering, anxiety, and death disappear?

We hear the swish of blood coursing through a gray heart. Or is it a spade? It’s actually a “d” and a “b” (db)—the David Blaine logo—animated to appear as if it’s been welded out of twisted wrought iron.

Enter “Jen,” i.e., world-famous actress Jennifer Lawrence, kicking back on a FaceTime call with Blaine, getting into character to assist in a piece of magic that, while designed to reach millions, will create an impression of two pals just killing time. Blaine instructs Jen to take out her own deck and “riffle shuffle” the cards (creating a hypnotic ASMR effect). He then asks her to choose a card in her mind and to say it out loud. “Jack of clubs,” says Jen tentatively. Blaine then instructs her to choose a number between one and 52 (she chooses 23) and to flip each card until she gets to that number. At the 23rd card, Jen flips over the jack of clubs.

This is when the public display of mentalism becomes extremely alluring, as Lawrence, a highly trained actress, warps the fourth wall of 5G. “No!” she screams, in a tone ordinarily reserved for horror films. “You’re a witch! You’re a witch! No!” We cut back to Blaine who smiles like an unpopular eighth grader who has finally found a way to interest the prettiest girl in his class.

But it’s not yet time to press the yellow thumbs-up emoji, not until Lawrence unleashes her plea: “One day before you die, are you gonna write a book and tell us? You CAN’T die! If you started a religion, I would follow it!”

Blaine smiles. He looks satisfied.

Hasn’t Blaine already started a religion? Or at least a cult? Blaine is shaman to the stars. He’s like a very dark Rick Rubin. In fact, the two bearded gurus (or Jew-rews) are chummy. A podcast hosted by Malcolm Gladwell features them in a conversation, Rubin having come out as a magic lover and devoted fan of db. If rap impresario Rubin is a touch rabbinical, then Blaine, by comparison, has been touched by evil. He’s basically trouble—a little like that weirdo Russian healer Rasputin who got in with the Romanovs before they started suspecting him as a conspirator and ordered him to be shot and drowned.

I was watching another of Blaine’s domestic celebrity ops—one set in Harrison Ford’s kitchen. By frame one, Ford already seems bugged-out. Perhaps he’s overwhelmed by the room’s demonic aura. Blaine shuffles and asks Harrison to think of a card (nine of hearts), as he teleports this card (nine of hearts) through a mysterious portal of time and space into the juicy interior of a navel orange.

“Here’s what we’ll do. Do me a favor ...” Blaine says, scanning and commanding the kitchen counter. He asks Harrison to grab a ripe orange out of a bowl of fruit, hold it steady on a cutting board, and hand him a knife, so that he may perform a C-section on the orange, and deliver the nine of hearts. Harrison’s eyes go into a hypnotic spiral, and he begins to breathe heavily, as if he’s going into cardiac arrest. He turns to Blaine and says: “Get the fuck out of my house.”

I replayed the video, pausing to study the intricacies of Blaine’s sleight-of-hand and to reverse engineer his switcheroo. But who would want to debunk David? I’m reminded of Robert Bresson’s 1959 masterpiece Pickpocket, and the 2018 Japanese film Shoplifters. The trick, in magic as in theft, is to be one step ahead and to never get caught red-handed.

Blaine’s celebrities who help him pull one over on us, are all of a piece: They’re not just big, they’re the biggest stars that Hollywood has to offer. And Blaine has a way of wedging himself right in there with them, allowing us, as viewers, to feel right at home—at Travolta’s, or sitting on Margot Robbie’s ping pong table watching Blaine tamper with her mind. Robbie—who is certifiably gorgeous—is visibly moved (her eyes get moist) when Blaine reads her mind, takes out a Sharpie, and crudely writes the word “BUNNY” on her sister’s hand.

Bunny? Like the generic bunnies magicians pull out of hats? No, this is a personal rabbit that Robbie conjures from deep within. But what matters is the way her astonished coterie of Aussies react—they turn away from Blaine as if to shield themselves from the diabolical force he emits, while Blaine acts unaware of his own mental potency. It’s as if he’s crashed yet another party and blasted his hospitable hosts with evil rays of psychic telepathy. He just can’t help it. “That’s not only weird,” says Robbie, staring at the word BUNNY, “but it’s really embarrassing!” She is now blushing as if she’s been exposed.

And Blaine is just as mischievous when he strips Will and the Family Smith, Kanye, Woody (Harrelson), Dave Chapelle … and I almost forgot, Bryan Cranston and Aaron Paul (aka Walter White and Jesse, from Breaking Bad). He asks them to hide a six-inch icepick face up under a bunch of tall Styrofoam cups while he’s out of the room. He then marches back in and begins smashing each cup with his bare hand, intuitively knowing which cup not to smash. A miscalculation wouldn’t be pretty.

And then Blaine defies our expectations and makes us a little wobbly in the knees. He unseals a small sanitizer pad, disinfects the ice pick with the care of a nurse-practitioner, and presses the icepick into the back of his own hand, somewhere between the complex of bones, tissues, veins, arteries, nerves, tendons, and muscles. He presses harder exerting force, and drives (or pretends to drive) through the spike until it is visibly pressing out through his palm—without even a drop of blood. “You’re out of your mind!” utters Paul, before adding, politely, “in the most beautiful way possible.” Blaine smiles, knowing beauty is all he’s ever been after.

What have we just witnessed? A beautiful optical illusion? A beautiful special effect using cameras and prosthetics? A beautiful, albeit mortifying, work of extreme body piercing? Has Blaine, the beautiful devil, played the ace of spades again, and won? I’m reminded of Full Metal Jacket, where we see the superstition-heavy card tucked under the band of a soldier’s camo-covered helmet along with the graffitied slogan “Born to Kill” and a pack of Marlboro Reds.

If something with this level of ambiguity cannot properly be called magic, then what can? And what is magic anyway? I typed the word into Google and quickly arrived at something called “black magic.” I began to read up on the history of “the left-handed path”—the use of supernatural shamanistic powers for selfish intent. I learned that back in the Renaissance, black magic was considered witchcraft. During the Inquisition, all the self-made diviners, charmers, wizards and even jugglers were shit out of luck—I mean life. According to the occultist and founder of the church of Satan, Anton LaVey (aka The Black Pope), “the Satanist, being the magician, should have the ability to decide what is just, and then apply the powers of magic to attain his goals.”

And what about believers in magic? What about their goals? Do they (do we) have any say in any of this? According to one of the most pioneering mentalists in the age of radio and television, The Amazing Dunninger, “for those who believe, no explanation is necessary. For those who do not, none will suffice.” Magic may therefore be seen as a game of getting believers to believe, and the nonbelievers to, well, exit the room. And while there’s no room for a WikiLeak in magic, magicians certainly play off our skepticism and are challenged to push the threshold of our willful suspension of disbelief.

Magic has always been a carefully set trap for the consumer. It is merchandise. I can imagine the classic hobbyist browsing the aisle of a local magic shop eying the spine of every cool paperback, pulling various props and kits off the shelf, reading the back of the package, and contemplating: “Should I splurge? Will this be the trick that finally magnetizes their admiration?”

Growing up in the burbs of Charm City in a sea of Baltimorons, I was exposed to a bit of hands-on magic, via my dad, a doctor by profession, and something of an amateur magician. On occasion, he’d pull out his dusty box of props. I seem to remember a velvet cape; a top hat that crushed down into a flat disk; a pistol that shot out a red flag with cartoon letters reading “BANG”; a plastic hollow baton stuffed with an endless chain of linked pink handkerchiefs; and a tricked-out deck of cards that could be made to look pierced by a very sharp pencil—but (Voilà!) without leaving any sign of being punctured. Dad would set up somewhere and invite us all in to view the same show he’d done as a teenager growing up in Stamford, Connecticut, in the ’50s, where he charged admission and ushered in the entire neighborhood, pocketing around a dollar in change.

The magician and the doctor are cut from the same cloth. Originally these two practitioners were one and the same. The first doctors, with their bag of tricks (ointments and remedies), were a bit more performative than today’s cool clinicians plugged into their magic diagnostic tablets. Drugs were administered with far-out incantations, wild dancing, and distorted grimaces. Prior to the white-coat and stethoscope costume, the family physician appeared more like a wily sorcerer putting on a phantasmic show, even when the pocks, rashes, and oozing sores failed to vanish.

The trick I most remember was the Detachable Thumb—a classic. My dad would perform this one on his patients and on his own children. When I saw that thumb tip slide away from the knuckle, I nearly sprained my eyelids. Talk about disbelief. And yet, it is this elementary thumb trick that lies at the root of so many of the most grandiose tricks in magic, like the sexiest of all—the one that employs the buxom blond assistant to (never mind misogyny) get cut in half.

Now that I’ve grown up and debunked the Detachable Thumb, as well as the Tooth Fairy, Santa, Nine-Eleven, and the president, I guess I’ve come to see everything in life as a trick. The cognizant mind prefers to see the detached units of life as one fluid truth, in order to construct this atomized fuzzy holistic thing called reality.

Apparently, my dad never outgrew his adolescent enthusiasm for evil, which impelled him in 1987 to throw us into the station wagon and blaze up the Jersey Turnpike to New York City in time for a Sunday matinee of Penn & Teller on Broadway. This was right after the dynamic bound-for-Vegas duo broke through, when they made a cameo doing a three-card monte on the streets of NYC in Run-DMC’s “It’s Tricky” video, which aired on MTV pretty much on the hour.

After my dad got the car parked (it did get towed, by the way), hustled us through FAO Schwarz, Radio City Music Hall, and into and out of a booth at the Russian Tea Room, we hunkered down in a cozy theater to enjoy this obnoxious loudmouth and his Buster Keaton-esque sidekick. But the show wasn’t quite cool enough to hold my adolescent interest. Let’s just say, it wasn’t the Rolling Stones.

Yet the fact that I was witness to a significant moment in the history of magic was not lost on me. Despite my teenage angst, I knew I was experiencing the cutting edge—the avant-garde, the “make it new” (Ezra Pound) moment of magic. Penn & Teller’s gimmick was pretending to FINALLY come clean—pretending, that is, to sacrilegiously teach us all the oldest tricks in the book of sorcery while catching us off guard and tricking us once again. That, in 1985 (think Ronald Reagan) was the name of the game.

By 2005, I was all grown up, and still disinterested in magic. But my dad persevered—he procured atrociously expensive tickets to some new-ish (rhymes with Jewish) magician named Steve Cohen, who was being written up in places like Forbes magazine for his expertly rehearsed act for small audiences out of his own luxury penthouse apartment in a posh midtown Manhattan skyscraper known as the Waldorf Astoria. His show was designed as a throwback to something called parlor magic, or millionaire’s magic. Suffice to say, I was deeply unimpressed by Cohen’s tedious mentalism—his psychic abilities came across, to me at least, as a blend of FBI background check and Asperger’s syndrome. It occurs to me now that for magic to work, sadly, the magician has to essentially go ahead and do THAT extreme thing you assume nobody would ever bother to do in order to pull off a dumb old magic trick—like memorize the birthdays of 50 strangers.

I was, however, taken by the architecture of Cohen’s apartment. And I could hardly suppress my desire to pull back the curtains and see the view. Had the mentalist read my mind, he surely would have known I was thinking about my once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see the Empire State Building from the most glamorous Art Deco corner room in the world. Immediately after the show I did mosey on over to the window and pull back the curtain. But before I could even enjoy three seconds of cinematic metropolis bliss, two security guards wired with ear devices nearly tackled me. I must have been inadvertently exposing a hidden mirror or something. They efficiently escorted me (and my family and parents) out of the room, down the elevator, and back out onto the sidewalk.

I was through with magic, but apparently magic wasn’t through with me. David Blaine, you might say, was on the way to save magic from cheesy sequined capes and jury-rigged rooms. In an early appearance on Conan O’Brien, in 1997, Blaine actually teetered on the cusp of cool. He spoke in a monotone, dressed in a baggy gray sweatshirt and black jeans. And most importantly, he was sporting a pair of Adidas Originals. In 1984, The Fat Boys made these kicks the iconic marker of vintage hip-hop. In “Jailhouse Rap” they wrote, “so I put on Adidas, headed out the door, as I pictured myself, eating more and more.” Two years later, Run-DMC said “my Adidas walk through concert doors, and roam all over museum floors”—at least that’s the way I heard it.

Early Conan-era Blaine is slouched, slumped, and simply nonchalant. He doesn’t speak so much as mumble. He seems unconcerned with ratings. It’s 1997, and his Mediterranean, olive complexion speaks for itself—it’s pre-terrorist chic. His eyes are their own mirrored shades. He gives off a brooding sense of danger, even when merely shuffling a deck of cards. Conan jumps back in shock the minute he appears, as if Satan has entered the studio. And that’s coming from a ginger.

A few years prior, on an earlier incarnation of the Jon Stewart Show airing on the newish MTV cable network, Blaine has not yet learned to walk through the stage doors in his Adidas. He’s still buttoned up in a tucked-in, starchy white shirt. He looks wet behind the ears, as if he’s been buffed up backstage by a pushy Jewish mother-manager. He walks out to a sizzling blues riff, introduced as “a psycho-illusionist” to a room of rowdy teenage boys who are all on their feet. Stewart then begins his intro: “Most of today’s magicians … they’re old, they’re beat! Kreskin? Over. Copperfield? Toast. Siegfried and Roy?” A huge grin forms—he almost laughs. “I don’t even think they’re magicians, but they’re easily like 500.” He gets the laugh.

Blaine begins a card trick but aborts. “Actually, you know what? I just realized, card tricks don’t play so well from a distance. Let’s not.” He sets down the cards on the coffee table. “Forget this! I’m sorry, I’ve got something better for you.” He spills out a box of 3-inch carpenter’s nails (a magic shop prop if there ever was one), hands a hammer to Jon, who then assists him (as the crowd cheers) by whacking one of the nails up Blaine’s nose. We brace for at least one spurt of blood, as Blaine calms us: “Don’t worry. It’s just an illusion.”

In ’97, when Blaine’s first television special, “David Blaine: Street Magic,” aired on ABC, it was Penn & Teller who endorsed it, saying that it “broke new ground.” A writer in Time also praised Blaine’s style, noting that “his deceptively low-key, ultracool manner leaves spectators more amazed than if he’d razzle-dazzled.” Blaine, who claims to have first seen Penn & Teller on MTV (presumably around when I saw them) must have decided to take the Run-DMC thing literally—to go urban. He was soon collaborating with the cameraman who shot the television series Cops for Fox.

Blaine did manage to get the kids to huddle around and watch him perform long enough to capture their reactions on tape (I assume he got signatures and paid them for their services), and it is their profound reactions that make the show bounce. In one clip, Blaine tricks a bunch of kids into thinking he’s actually levitating. Is it the Balducci Effect? Or something even more extreme? The hand-held camera focuses on the audience’s contorted faces at a moment of rapture. “How did he do that?” asks one bewildered kid.

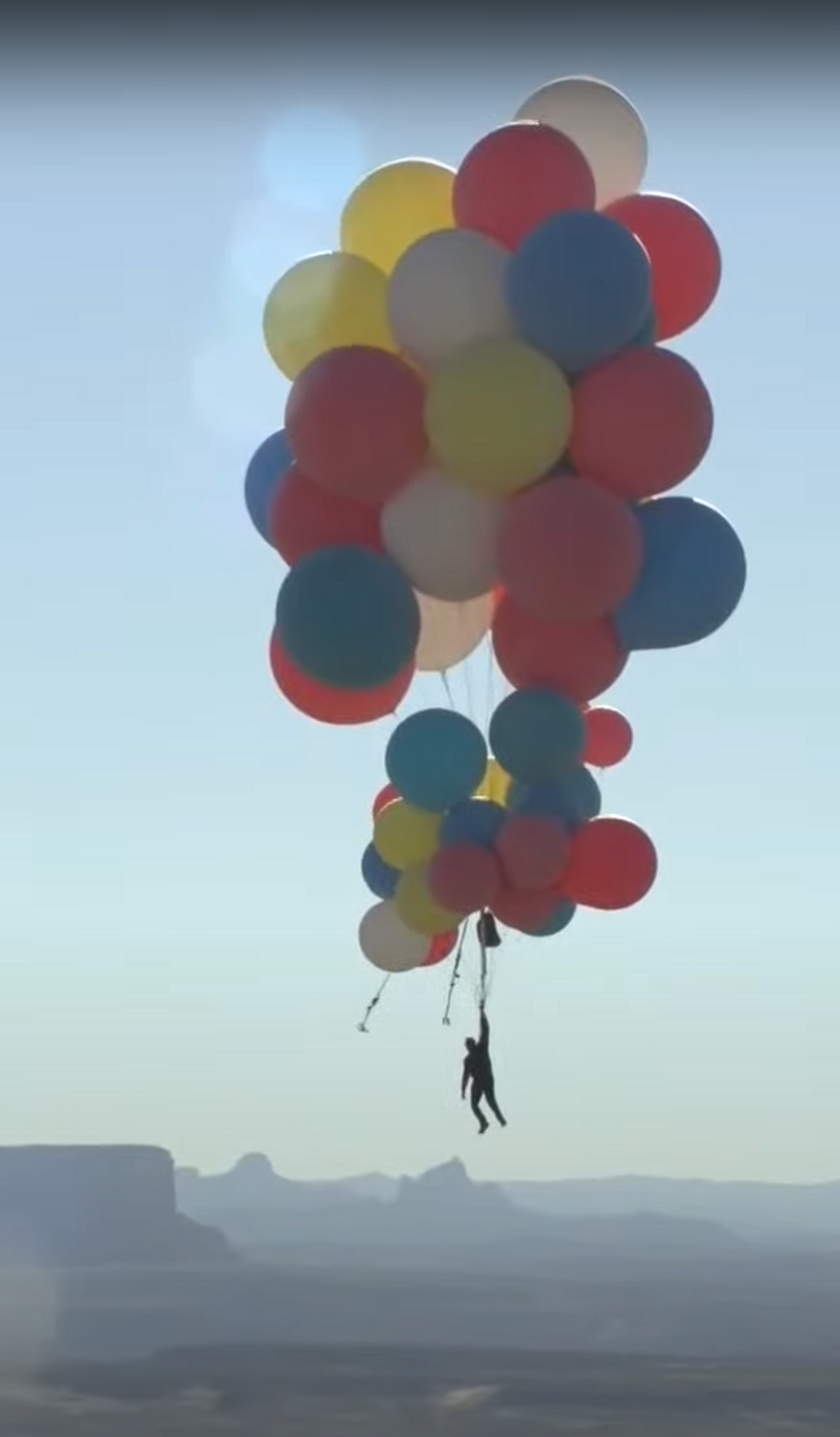

2020. Inches of levitation have now grown into 25,000 feet of ascension. Blaine resurfaced, and he wasn’t wearing a mask. And he pulled off arguably his most epic magic trick/endurance stunt to date, brought to us, at inconceivable expense by YouTube Originals. It seems that Blaine was given carte blanche to a nearly three-hour live platform. To do what? To ascend (with us, up close) to a very peaceful, oxygen-depleted place far above the clouds.

Before his ascension, we get to spend time with Blaine on the ground, in his final phase of preparation. It is tense, for sure. We are somewhere in the Mojave Desert in the swing state of Arizona (is this relevant?). We tour the sandy site with Blaine, get introduced to his “team” of leading scientists in aeronautics and astronautics. It’s like Cape Canaveral prior to the Apollo 11 launch in ’69. Blaine’s stunt has NASA written all over it. Or is he having a pissing contest with Elon Musk, who promises to take us to Mars?

Anyway, Blaine, basking in his highly idiosyncratic blend of ultra-sincerity and con man, explains how hard he has trained in order to minimize risk. He introduces us to his coach, an expert daredevil skydiver named Luke Aikins. He explains that it took 500 jumps to earn his pro skydiving rating, and that he had to get a hot air balloon certificate and even a rarer helium balloon flying certificate. He explains that he has learned the tricky skill of navigating wind currents, while showing us an image of “catastrophic balloon failure.” Next, he walks us through the biology behind hypoxia (lack of oxygen to the brain, which shuts down the mental functions). And hypothermia, which, at high altitudes causes the body to begin to quiver uncontrollably.

Blaine explains how he will attempt to climb into his parachute only after he ascends past a certain height (a somewhat arbitrary additional challenge). Only then—assuming he is not unconscious—will he release himself from the balloons and skydive back down to earth, pull the rip chord, steering past any trees, power lines, and fences to find a relatively flat place to land. Blaine’s macho team of experts also includes a weatherman who cuts in to inform David that the conditions are perfect but likely to change; he urges him to seize the moment. Blaine seems palpably exhilarated—it is showtime, and you can’t fake predatory fear in the pupils.

The cognizant mind prefers to see the detached units of life as one fluid truth, in order to construct this atomized fuzzy holistic thing called reality.

The team straps, buckles, and wires him into a wearable harness with a metal arm that reaches like the Statue of Liberty up to the giant bunch of oversized colorful inflated helium balloons and to the welded core of electronics camouflaged within. In other words, Blaine will not actually be gripping the strings of balloons, and hanging by his own weight from his arm, but will be rigged to an armature that will provide considerably more structure.

My mind wanders. Who else, other than astronauts and ETs, will be where he is about to go? I think of the very credible recent report by three commercial pilots of a man coasting along in a jetpack at altitudes only trafficked by 747s. Fake news? Clearly. But nothing seems fake on this YouTube Original. I’m ready to watch (check); the balloons are ready (check); licenses obtained (check); the coaching is complete (check); the parachute is loaded (check); the cameras are all in position (check); the backup oxygen tank (check). Check, check, check and check.

Blaine drops the first of many ballasts, and the balloons silently, eerily begin to lift off the ground. He is giddy, as if wandering around the parking lot of a Grateful Dead show taking small hits off a balloon of nitrous oxide.

Blaine explains what motivated him to do this astonishing stunt, which is deceptively hazardous despite its whimsy. We learn that it’s actually inspired, at least in part, by his 9-year-old daughter, Dessa. “My daughter was at the last one when she was 2 years old.” Here he’s referring to “Electrified: One Million Volts Always On” (2012). “It was so difficult and extreme that I decided right then and there that I would find something that would inspire her, not scare her.” He continues, “my hope is that it brings happiness to people for a moment … When I look up and see this,” he says, turning to face the balloons, “it just makes me smile.”

Recently on Joe Rogan’s podcast, Blaine promoted Ascension. He was hyper, almost manic—definitely over the moon about his upcoming stunt, thrilled by his ability to deprive himself of oxygen to the point of blacking out, which has become a form of recreation for him. He is so enthusiastic about this process that Rogan taps his fat cigar, grins, and rolls his eyes. It’s a moment laced with sleazy innuendo that seems to refer to the dangerous act of auto-erotic asphyxiation. Moments later, Blaine takes a swig of water, belches a few times, and regurgitates a live frog which hops around the table near the microphone. It’s a trick he’s performed countless times.

But Blaine’s Ascension is not an old trick, nor is it intended to be creepy or grotesque. It is designed to be wholesome—and maybe even to clean up his somewhat dirty reputation. In 2017, he was #MeToo’d with allegations of sexual assault that he vehemently denied. In 2019, Blaine was investigated by the New York City Police Department concerning other similar allegations. It doesn’t help that the name David Blaine showed up in Jeffrey Epstein’s little black book (along with many of the most filthy or filthy rich blackmail-able individuals in the world). According to New York magazine, back in 2003, Blaine “put on a private show for Epstein’s dinner guests … The dinner was organized by Ghislaine Maxwell and included a group of young women who were introduced as Victoria’s Secret models.” You can see why Blaine might want to fly away from planet Earth ASAP.

Dessa (her mother is Blaine’s former partner, Alizée Guinochet) is helping Blaine transform his act into good clean family entertainment. Prior to liftoff, they have a few tender, father-daughter moments, where Blaine offers reassurance that he’ll be back on the ground soon. They say the words “je t’aime” to each other, conjuring a tinge of sadness, as if they both know that Blaine is potentially on his way straight up to heaven, where the angels speak French.

Blaine continues to drop ballasts and rise to the edge of the Earth’s atmosphere, to a height few men have ever gone with the use of only their lungs. At around 20,000 feet, he is convinced to take a hit of oxygen from the respirator. He inhales presumably seconds before blacking out, and I’m once again reminded of COVID-19. As Blaine rides out the horror of lung failure, many of us are down here on planet Earth in masks, terrified, as of late, of the very air we’ve been enjoying our entire lives. I think about men and women who have been transported to hospitals, and then to morgues—or somewhere in between, hooked up on life support, face down on hospital beds, shot full of steroids, fighting for a single inhalation. I think about the scramble for ventilators, and for medical professionals who know how to use them. Ah, David Blaine!

All to create a beautiful image? Like a French Impressionist painting? If this is a signed “db” original, (and a YouTube Original), then I’m afraid it’s not very original. If anything, the image of a person lifted off the ground by a big bundle of colorful helium balloons has itself been lifted. Not from the 2008 animated Pixar film Up, but from Up’s source. Blaine mentions being taken by his mom when he was little to “a movie about a boy who floats away on a balloon”—this would have had to be the 1956 Academy Award-winning French short Le ballon rouge (The Red Balloon). In the sentimental final scene, a Parisian boy is visited by hundreds of escaped balloons which seem to come streaming across wind currents from all over Paris floating down out of the sky like helium-filled puppies. They hover over, twist together into a bunch, and dangle their braided strings down to the boy. The boy grabs on and floats right up into the pale blue sky over Paris. It is this melancholy magical climax that won the film the Palme d’Or at Cannes, and that tattooed this poetic image into our collective imaginations. It’s a moment of unforgettable whimsy so iconic that it can’t possibly belong to Blaine without, at the very least, the assurances of a very expensive fair use copyright lawyer.

What is it with balloons anyway? Especially the red ones. Are they symbolic or something? From boy, to clown, to artist, to magician, and back again, the balloon seems too menacing to be mere nostalgia or melancholia. A few years ago, the very dubious artist known as Banksy used some sort of remote-control gadget to slide a picture of a girl walking along with a balloon right out the bottom edge of its gilded frame as if it were a paper shredder, just minutes after the unanticipated kinetic artwork was sold for $1.37 million at auction. It was an outrageous real-time DC comic-book crime.

In the high ‘80s, a song “99 Luftballons” sung in German, if you can believe it, by someone called Nena was in the rotation on MTV for months. It is arguably the most mysterious one-hit wonder ever released. All I know is that it had something to do with the Berlin Wall.

Blaine’s Ascension (his will to defy gravity and float away) did not just happen overnight. He worked his way up to it. It was back in the ‘80s when he began to wade into the murky waters of Harry Houdini—to venture, that is, beyond mind-tingling magic tricks into gut-wrenching visceral genres of endurance and escape. He was compelled to do the type of things doctors are always saying can’t be done—like living in a glass box for 44 days (in London) on nothing but water, a gesture that Blaine is proud to boast garnered the attention of the New England Journal of Medicine. “They actually used me as research for science.”

Blaine became obsessed with seeing how long he (or any living creature with lungs) could hold its breath underwater. Doctors insisted that any duration over six minutes would cause permanent brain damage, and yet, he’d seen a news story of a child who fell through ice, stopped breathing, was rescued, and miraculously brought back to life and to a full recovery. Could the human body, or more specifically the Blaine body, defy biology? In his quest for answers, Blaine got down to work devising the ultimate magic trick: to go on living without breathing. He first, naturally, went to Home Depot, where he bought supplies (plastic tubes and duct tape) in order to fabricate a “re-breather”—a kind of CO₂ scrubber, that would be inserted down his throat. I believe this is called life support. Not surprisingly, Blaine’s da Vinci-esque, home-brewed machine failed. He stubbornly tried a novel form of “liquid breathing” which also failed for lack of gills. Blaine then set out to invent a heart-lung bypass machine that could be surgically attached to an artery in order to oxygenate his blood, thus circumventing his respiratory system. “Another insane idea, obviously,” says Blaine, who then researched pearl divers and was soon able to purge (or hyperventilate and rid his lungs of CO₂), relax, remain perfectly still, and hold his breath for absurdly long periods of time (we’re talking four to five minutes). In other words, he learned to slow down and nearly stop his heart using his mind.

Why? In his famous TED Talk, Blaine reveals just how skilled he is at storytelling. Standing before an auditorium mumbling about his unfortunate childhood (he was born with inward-pointing feet and asthma) he seems exhausted and depleted emotionally by certain memories. It’s as if he’s in recovery, detoxing after a particularly draining stunt. “As a magician,” he says, “I try to show things to people that seem impossible. And I think that magic—whether I’m holding my breath or shuffling a deck of cards—is pretty simple. It’s practice, it’s training, and it’s. …” Here, he gets choked up and fights to retain his composure. “It’s practice, it’s training, and experimenting—while pushing through the pain, to be the best I can be. And that’s what magic is to me.”

A standing ovation! As far as TED Talks go, it’s a keeper. The clicks don’t lie. (Well they do, actually, but …)

But why does Blaine almost cry? For one, in the previous 30-some minutes he has just chronicled a harrowing stunt that humiliated him on national television and nearly cost him his life. In “Drowned Alive at Lincoln Center” (2008) he succumbed to hubris and the demands of show biz. “Watching someone hold his breath and almost drown,” he says, “is too boring for television. So they added in cuffs.” (“They,” being the executives). The Houdini-like manacles, he admits, were the critical mistake—adding anxiety and a small increase in physical exertion that broke his concentration and stole fractions of his oxygen supply. Footage shows Blaine submerged in the big glass bowl with his eyes clenched and bubbles beginning to escape from his nostrils. This is when divers had to swim down and unlatch his cuffs and pull him to the surface. Shit was real—and he barely made it.

Blaine seems to be especially comfortable talking about his failures, which is kind of amazing given the world of arrogant denial we now live in. In “Frozen in Time,” performed in Times Square in 2000, he made another near-fatal miscalculation—he told his team to ignore him should he eventually plead to be let out. After standing upright for over two days inside a hollow block of ice (the claustrophobic space is only a little bigger than his own body), he began to completely fall apart. “There was a point when I crossed over, I completely lost track of time, I was slipping in and out of consciousness, I thought this was never gonna end … I was convinced I was dead … and that Josie [his girlfriend at the time] could no longer see me … I thought at that point that my mind was permanently gone.”

Eventually Blaine was cut out by chainsaw and delicately placed on a stretcher. The tape is grim—he’s clearly experiencing hypothermia, sleep deprivation, starvation, and has gone into shock. His clothes are soaking wet. A little beanie hat has begun to slip down over his eyes, but he hasn’t the strength to lift his arm and adjust it. He looks like someone being rescued from an avalanche. He tries but fails to speak words into a microphone being held out in front of him by some reporter. He breaks down into tears as the crowd cheers him on. A ticker tape is seen behind him. He finally manages to grunt, “Josie, I’m weak, I’m weak. Something is wrong.” Such emotion is very atypical of magic.

So what made Blaine almost cry in his brilliant TED Talk? It may have something to do with his mother, a former fashion model of Russian Jewish descent who raised him in Brooklyn, on welfare. His father, a traumatized Vietnam vet of Puerto Rican and Italian descent, was, and presumably still is, absent. When he was 9, his mother remarried, and his new family moved to the suburbs of New Jersey. By then, Blaine was already deeply infatuated with magic, consumed by a card deck his mom had given him. In one interview Blaine laughs as he remarks that whenever he’s on the phone with any of his magician friends, they can always be heard shuffling a deck of cards in the background.

At age 4, he used his first “magic” deck to perfect a trick that creates the illusion of a pencil puncturing a card without leaving a hole. (Sound familiar?) Blaine also began to perform endurance stunts at an early age. I’m not sure if it began on Yom Kippur, but he wound up fasting for six days! (My question for Blaine is, have you ever read A Hunger Artist by Franz Kafka?) At 10, his family scraped together enough money to send him to a fancy summer magic camp called Tannen’s, where he was encouraged to practice obsessively.

When Blaine was 19, his mother became ill with ovarian cancer and passed away at 48. The loss led to Blaine’s obsession with death. He describes how experiencing his mother’s deterioration led to his first endurance stunts, all of which have been attempts, in one way or another, to understand what she went through as she was dying. And I’d respectfully add, where she went after dying. Soon he was getting hired and paid generous sums to stand around doing card tricks at private parties hosted by millionaires. Blaine also began to crash tables in fancy Park Avenue restaurants where celebrities were dining—Leonardo DiCaprio was one of his first victims (today they remain the best of friends).

In an interview with Kalush and another early influence, Bill Harris, Blaine explains how hard he had to work to find his own style. How he had to reject so many magicians that he admired like Yuri Geller (the spoon guy), or even Doug Henning (the box guy), and of course the badass Ricky Jay. Eventually, he invented his own brand of what he calls “Urban Shamanism”—which he reduces to a basic equation: “You enter somebody’s life, try to affect them for a moment, and you wander away.”

Eventually in 1999, Blaine figured out how to stand out from the pack and create some really big buzz: Donald Trump. Throwing vulgarity to the wind, he pitched a classic from Houdini’s repertoire “Buried Alive” to Donald. In this stunt, Blaine is sealed in a thick plexiglass box, which is not covered in dirt but by a 3-ton tank of water, for seven days. Trump takes the stage delivering something of a christening/eulogy/earth-breaking ceremony that takes place on a small untranquil plot near the East River Drive: “David, I can just say, you’ve got great courage,” says Trump (by now you know the cadence). “I wouldn’t do this on any kind of bet, but it’s gonna be interesting. And lots of luck. And enjoy it! And I’ll see you in about a week—I hope. I hope.”

Blaine has claimed that the stunt was a way for him to lay in bed with his mother, and then to lay in the grave with her. “In many ways, I endured a week buried underground as a tribute to her … I guess I am trying to put myself in a position where I could understand what she went through.”

Various tricks have given me an opportunity to observe Blaine’s tattoos. One on his wrist is his db logo. Another, at first, seems to say EARTH, but then, like an optical allusion, flips to the word FAITH. Across his back is a reproduction of Salvador Dali’s “Christ of Saint John of the Cross.” But the most compelling tattoo is found midway down Blaine’s forearm; it is the concentration camp number that belonged to Primo Levi: 174517.

It makes perfect sense that Levi, an Italian Jewish chemist and author, who wrote so eloquently on surviving Auschwitz and on The Periodic Table of elements, is one of Blaine’s heroes (Levi died in 1987, after falling from a third-story apartment). And there are other moments when Blaine shows his Jewish side. When asked if he was concerned that Dessa might follow in his harrowing footsteps, he compares himself to an overly protective Jewish grandmother. “If she bumps her leg, I …” He shrieks.

My favorite Blaine stunt is called Bullet Catch (2008). It feels like it could be taking place in CIA headquarters, or the latest Jason Bourne flick. Blaine has invited a marksman (his old pal Bill Kalush) to stand across the room (about 20 feet) line him up in the green laser scope of a .22 caliber rifle, and pull the trigger, firing a bullet into Blaine’s open mouth. I’m reminded of the artist Chris Burden, who, back in the ’70s, had a marksman shoot a puny little bullet into his arm. Clutching his bloody arm, he poses in a white T-shirt for a documentary photograph looking like some nervous kid who messed up playing with his dad’s loaded firearm.

Blaine, a man with a Las Vegas appetite for upping the ante, appears to catch his bullet, not in his fatty bicep, but in a small steel cup hooked to his teeth and resting on his jaw. Even a bullet made of Jell-O would have probably blown his head off. A high-speed phantom camera captures the moment at 10,000 frames per second and, what can I say? It’s radical. “Obviously,” says Blaine, “I cannot flinch or it’s a real problem.”

Blaine is also clever enough to prep us by telling us that 20 magicians have died attempting the trick, that Houdini wimped out of doing it, and that even Blaine’s own producers folded only hours before the stunt due to the obvious legal ramifications. Then, a few seconds later, it’s done. All done! Like getting a shot. Blaine reaches into his mouth, removes the mashed metal bullet, walks over to bear hug Kalush, and dishes out a round of high fives to his team. And for a moment, death is only an illusion.

Jeremy Sigler’s latest book of poetry, Goodbye Letter, was published by Hunters Point Press.