Documenting Nathan Hilu, the Great Lost Jewish Outsider Artist

A new film explores the life of a mad, reclusive genius who depicted the vanished world of Yiddish America

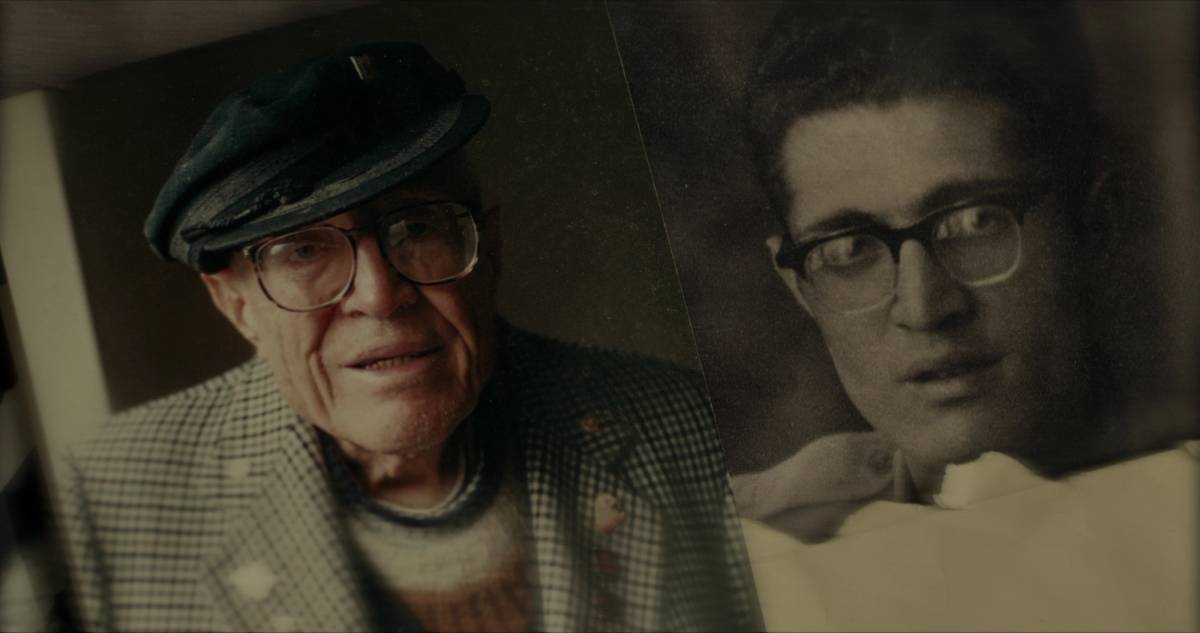

You may recall a man named Nathan Hilu. Tablet wrote about the World War II veteran more than 10 years ago, when he was 87, and declared him the “most significant Jewish Outsider artist you’ve never heard of.” The occasion was his recent discovery by a curator and a consequent pair of New York shows of his idiosyncratic and prolific artwork depicting, in crude marker and frenetic crayon or pastel, memories from his life. I wish I could say that over the following decade Nathan went on to garner acclaim, notoriety, Instagram collabos with fashion brands, pieces bought by major art institutions; that he was feted from Art Basel Miami to the Venice Biennale and was made rich. Alas, instead, Nathan Hilu celebrated his 90th, his 92nd, his 93rd birthdays while remaining the most significant Jewish Outsider artist you’ve never heard of.

You may also vaguely recall the Nuremberg trials. Nathan Hilu was there as a U.S. Army soldier, assigned to guarding the prisoners, who included—as Nathan would tell you and represent in his art over and over—Albert Speer, Hermann Goering, Julius Streicher, and a host of other historically significant people, who aimed to murder people like Nathan Hilu.

Pulling on the noble rope now to heave Hilu out of obscurity is a new documentary by a young Israeli vet and film editor, Elan Golod, titled Nathan-ism, premiering later this month at the Hot Docs festival in Toronto and also screening at Tel Aviv’s Docaviv in May, where according to Golod it is slated to receive a Yad Vashem award for “Cinematic Excellence in a Documentary about the Holocaust.” The film does not so much follow Hilu as sit opposite him, a mad tummler of memory, as he continues to draw and, as they say these days, speak his truth.

Nathan’s truth is a clinically obsessive fixation on visually representing things that he remembers from a Yiddish American past that is no longer present except in his mind: His encounters with I.B. Singer and the radio man Zvee Scooler on New York’s Lower East Side, the Yiddish-language versions of the Bob Steele cowboy movies he saw in Pittsburgh as a kid, kosher lunch counters, biblical tales, his Syrian Jewish heritage, and Eastern European lore. To manifest these memories, Hilu employs permanent markers, crayons, pastels, tape, glue, cutouts, scrap paper and cardboard. His art is a combination of glorified stick figures and explanatory words in English and Yiddish, and it has a distinguished, original, and immediately recognizable style. As Nathan-ism presents him, Hilu appears to do little else in life except draw these memories, and comment on them, to whoever will listen.

A portrait of obsessive compulsion, personal neglect, and the ravages of time, Nathan-ism is also essentially a gripping if simplistic account of the Nuremberg trials, and of the power of documentation to work in support of memory. This pivot, which owes its genius to Nathan himself, captivatingly expresses the Pynchonian idea that the only rational lens through which to understand Nuremberg and everything that led to it are the subjective, indelible scribblings of an insane man.

Supported by the Steven Spielberg-funded Jewish Story Partners (Steven’s sister Nancy sits on the board), Nathan-ism betrays the hallmarks of having been workshopped in the homogenizing doc-fest churn. Given the funding mechanisms available for stories like these, there may not have been any choice but to accept the funders’ notes. As such, Nathan-ism suffers from many of the clichés of contemporary documentary-making: talking-head commentary, stock archival footage, voiced-over animation, and the intrusive presence of the filmmaker. All four techniques rip you away from the film’s strength, which is firsthand interaction with the ball of consumptive fire that is Nathan himself, whose defiant, listen-to-me voice clamors into the higher registers of repetition before settling back down to a dimmed-eyelid monologue that closes the door on the outside world.

Slouched, hunched, doubled over by time, wearing colorful sweater layers tucked into his high-waisted pants, Nathan pleads for Jewish things not to be forgotten. Meanwhile, his knobby, liver-spotted hands continue to draw. Permanent markers squeak at each stroke, a mouselike soundtrack. Crayola nibs are thrashed across the page with the gusto of a 3-year-old. (Notably, out of courtesy or perhaps decency, there are no wide shots of Nathan’s apartment, only close-ups of elements in it suggestive of a broader neglect, like a cloudy goldfish tank, lest you judge Hilu by his impoverishment.) The question is whether Nathan, wearing a wool knit beanie under a wool sailor’s cap, will disintegrate right before our eyes, or if by some miracle he will hold on to draw another day. A scene in a hospital bed shows him connected to medical machines that he ignores while, unimpeded by an oxygen mask, he narrates another memory he’s busy drawing, squeak, squeak, squeak.

If the documentary feels thin when one of the talking heads comments on Nathan’s existence or the contexts in which he lived, it’s because Nathan comprehensively missed the big time. Golod mines what gold there is, visiting the Library of Congress to talk to an archivist in the Veterans History Project, which keeps a copy of Nathan’s memoir, reinterviewing the people behind a scuttled attempt at a previous Hilu book project, and following a freelance archival researcher on the microfilm hunt for an official Army script bearing the typewritten markings “Nathan Hilu” that might confirm, deny, alter, support, or otherwise fact-check what Nathan claims to have seen. This last, in the final third of the film, is set up to be a quest whose stakes are no less than the nature of documented truth in the face of Holocaust denialism, an existential load that ultimately it struggles to bear.

It’s hardly a spoiler to say that Nathan does not survive the end of the film—he died on April 19, 2019, to no obituaries save for a small one in The New York Times generously purchased by his main champion, the Hebrew Union College—a final irony for a self-described “memory man” obsessed with documenting the past. Scenes of his burial at Calverton National Cemetery on Long Island are some of the film’s most moving, from the sparseness of his pine coffin attended by a handful of aging, betokened WWII veterans, to the gravity of the ancient military rituals of flag-folding and the Star of David engraved into a headstone in a sea of white marble. If Nathan’s core obsession is his having been a witness, just showing up on time to get this burial ceremony on film feels like an unheralded act of heroism for which Golod richly deserves the Yad Vashem prize, though it should be shared with Laura Kruger, the HUC museum curator who discovered Hilu and is with him to the very end.

The imbalance between the hoard of material Nathan himself has produced in the decades of his scribbling and the thinness of both the official paper trail of his life and the amount of people he seems capable of motivating to care about him creates a central tension that largely goes unresolved in the film, or elsewhere. Despite the best efforts of a handful of academic curators, Tablet’s own journalist, and now a documentary filmmaker, we continue to know almost nothing of Hilu’s personal life, his four estranged siblings, all younger, all now dead, why he never married, or anything of the practicalities of his life beyond his compulsion to draw mental images from his Jewish past. I don’t blame the filmmaker for this: Nathan himself—or more precisely his madness—presents an impenetrable fortress, refusing again and again to be pushed into self-revelation. He is also, by virtue of his insanity and humility, incapable of making broader conclusions about the significance of his obsessions, let alone of defining the meaning of Nuremberg. His commentators hazard their best guesses. We are left with a genizah; the paper outlasts the man.

Readers who remember significant recent documentaries may think of the Suharto cronies from Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing—another meditation on the aftereffects of mass brutality on individuals—though no one has ever suggested Nathan’s compulsions are born of his wartime experiences. Closer kin include Kusama: Infinity, on another artist with a “unique, visionary expression of personal neurosis,” and Richard Press’ Bill Cunningham New York, about the similarly obsessive, longtime New York Times fashion street photographer who shares Nathan’s irrepressible fire along with an inscrutable inner life.

Many an art-bio doc is powered by the question of if and how the subject will be discovered or achieve “success” before his or her own obsessive madness (the very quality needed for artistic accomplishment) wins out. Cunningham became famous and celebrated in his lifetime, earning an achievement award at the Paris fashion shows that serves the doc’s redemptive narrative arc. (The late Cunningham himself admits he was nuts, so there’s no harm in that comparison to Hilu.) Kusama, for her part, is today enjoying a lucrative collabo with Louis Vuitton.

Nathan-ism concedes that battle early on, though Nathan claims to have found recognition in the very fact of the filming, shortly before dying. But instead of acclaim and riches, at the end we get Nathan’s pleading, lonely voicemail messages to please come over and visit, he needs you, he’s grateful.

Will some fresh attention here help the cause of Nathan Hilu’s interesting, moving, enormous, and possibly important output of outsider art, garbage bags and lockers full of it? In my optimistic moments I would like to think yes, and moreover that he earned it: that our as-best-we-could-muster catalogs of the obsessively self-documenting existence of Nathan Hilu will cause his art and some part of his life to—for a time at least—not be lost to oblivion. In that spirirt, may Tablet’s own reporting, Golod’s documentary, the Library of Congress’ Veteran’s History Project, the Hebrew Union College, a few collectors and curators such as the valiant Laura Kruger, the foundation money, the festival prizes—hell, even this review—serve like one of the squeaky strokes of Hilu’s Sharpie pens to help say that we witnessed this visionary man, that he drew what he saw, and that he was.

Correction: An earlier version of this article referred to “Nancy Spielberg’s Jewish Story Partners” and has been updated to clarify her role in the organization.

Matthew Fishbane is Creative Director at Tablet magazine.