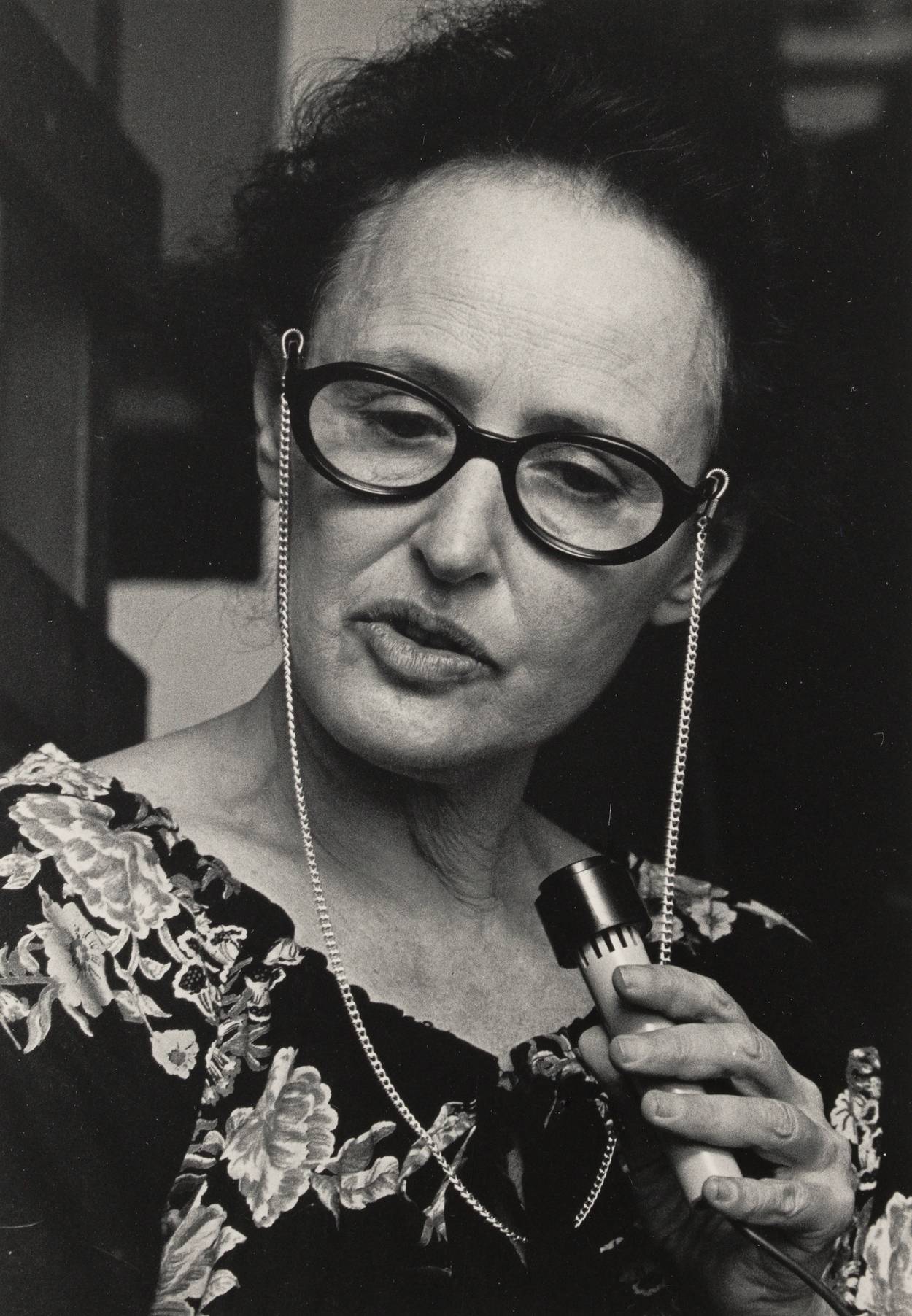

The Beautiful, Fractured Life of Dorothy Dinnerstein

Expansive, intimate, and wise, the late author of the newly reissued feminist masterpiece ‘The Mermaid and the Minotaur’ sought to change the alchemy of the battle of the sexes

I recently read Dorothy Dinnerstein’s 1976 classic The Mermaid and the Minotaur, with a laugh—and a sob—of recognition. So brainy, so nonlegislative, so gorgeously written, so humane. She was “supremely impractical in the best utopian sense,” wrote the theater artist Karen Malpede in a 1993 tribute to Dinnerstein in the Women’s Review of Books, a year after her death. She was a “fiery visionary innocent Blake imprisoned in a distinguished professor of cognitive psychology.”

It is a relief to read a womanifesto devoid of the language of #MeToo and intersectional politics. It’s not merely that these books—with their burnishing of female victimhood—tend to be misguided, but rather that there is something mean-spirited and unimaginative about them. Dinnerstein is expansive, intimate, and wise. She is concerned with what used to be called interiority, as well as with the links of misogyny to environmental catastrophe. And yet, given where we are, I wonder who the Other Press is republishing this feminist masterpiece for.

Dinnerstein did not see her opus as either a scholarly or a scientific work. The most pragmatic takeaway from this dense brilliant volume is that men should also participate in child care, which has sort of happened in the 40-some years since the publication of the book. And yet, to reduce Dinnerstein’s argument to the recommendation that we should have more stay-at-home dads is to not read it closely. Shooting from the radical heart of second-wave feminism, she refused to care about agenda setting and political relevance; “it was against my principles,” she writes in the forward.

The experimental psychologist wanted nothing less than to change the alchemy of what used to be known as the battle of the sexes. Like many second-wave feminists, she traced that battle to the ideas of Freud’s Civilization and Its Discontents. Her analysis is profound though her tone can be lighthearted. Chapter 4 is titled “Higamous Hogomous” after the old poem. She draws much from Melanie Klein’s essay “Envy and Gratitude,” and she pins blame on both sexes for not wanting to grow up. In a remark that strikes me as both typical of her complexity and of her prescience, Dinnerstein writes in the forward to the 1976 edition that “consent has suffused both what was joyous, loving, and sensible in each of us and what was closed off and obtuse, mean and rejecting, crazy and sad.”

Running through and on top of The Mermaid and the Minotaur’s brilliance is its labyrinthine structure. In a super-scholarly way, she prefaces most chapters with notes. And she drops into the chapters themselves 21 boxes, labeled A through P. Yet these boxes, whose contents can digress, might be considered the antecedents of hyperlinks, looping backward, shooting forward, commenting on the text and containing extended summa on the work of scholars and writers, such as on Norman O. Brown, Lewis Mumford, and Herbert Marcuse.

Dinnerstein’s sentences all sting.

The sexual arrangement, Dinnerstein writes, is a charade where “generation after generation of childishly self-important men on the one hand, and childishly play-acting women on the other, solemnly re-create a child’s eye view of what adult life must be like.”

On sex, “in lovemaking, both man and woman make this direct attempt to repair the old loss. Each of them does so first-hand, by taking bodily pleasure, and vicariously, by providing pleasure for the other person. But the balance tends to not be symmetrical.”

On ambivalence about growing up: “in some part of ourselves, we do not want to be our own bosses.”

On female collusion about inequality: “It’s easier for women than for men to see what’s wrong with the world that men have run. Not all women who see this, however, are ready to understand their collusion in that process.”

Dinnerstein’s fierce and beautiful book comes out of a fierce and beautiful life that was not without its aporia and fractures. The writing of The Mermaid and the Minotaur, which took nearly a decade, was abetted by numerous friends, including Joan Herrman, a graduate student of Daniel Lehrman, Dinnerstein’s third husband. “I was her amanuensis,” said Herrman, whom Dinnerstein thanks in the preface for writing a draft of Chapter 8. Naomi May Miller, an emeritus professor of social work at Sussex Community College and Dinnerstein’s daughter, who was one of the book’s outside editors, said, “Dorothy wrote in sentences that were three times as long as the ones that came out. Dorothy had endlessly long footnotes. She had no problem with a footnote that was a page and a half long. It was Talmudic. ‘Freud had that. Klein had that.’”

The Mermaid and the Minotaur was edited by the legendary editor Frances McCullough, who had published The Bell Jar and was then at Harper & Row. “Fran suggested the boxes,” said Miller, adding wryly, “The WASP met the Jew.” She said, “Fran found a way to contain this very logical but very non-linear thinker.”

But how did the book get to McCullough in the first place? Miller remembered that in 1973 McCullough discovered Dinnerstein after Joan Herrman, who was in a therapy group in New York City with McCullough’s secretary, gave her a chapter. (Herrman, who now lives in Scotland, did not recall this incident although she noted that Dinnerstein chose not to go with the feminist Virago Press.)

The Mermaid and the Minotaur was a minor hit. It was a finalist for the National Book Award. Vivian Gornick wrote that it “speaks eloquently through feminism to the history of organized human life” in her New York Times Book Review rave. Nonetheless, today it remains less read than other classics of second-wave feminism.

Dinnerstein wasn’t interested in organized political activism, and her engagement with Freudian theory might have been—might be—too esoteric for the ordinary reader. However, as I began to research the book, I discovered that biographical information on Dinnerstein is thin. According to her daughter, that is how she wanted it. Although the feminist Ann Snitow wanted to write her biography, Naomi Miller said, Dinnerstein “wanted her private life private.”

Who was the woman behind the book, then? Dinnerstein was born in New York on April 4, 1923, and spent her childhood in the Bronx. Her younger brother, Albert, was born four years later. Her mother’s family came from Bialystok and her father’s from Minsk. Her father, Nathan Dinnerstein, who was born in the United States, was an architectural engineer whose business collapsed during the Depression, when he worked as a bookkeeper in his brother-in-law’s junkyard before dying in 1947. Dinnerstein’s mother, Celia Moed Dinnerstein, who emigrated at the age of 2, worked as an administrative assistant at the Bronx Family Court.

It is interesting to note that in a book about mothers, Dinnerstein does not write explicitly about her own parents. However, in the preface, she mentions that three of her grandparents were victims of the “crude violence” of “societal expectations around gender.” The most vivid instance of this injustice was her paternal grandmother, Esther, who lived half the year in Brooklyn but abandoned her family for the other half to run a boardinghouse in Jeffersonville, New York— a “cahelaine,” said Harvey Dinnerstein, Dorothy’s cousin, using the Yiddish word for a place where people gather but cook alone.

Esther Dinnerstein dabbled in painting and the violin, but she excelled in neither. Her six children visited during the summer but the rest of the year, they were largely on their own. Whereas other Jewish families produced lawyers or doctors, said Miller, the Dinnersteins turned out artists and analysts. Like Dorothy, her younger brother, Albert, became an experimental psychologist. Harvey and his brother, Simon, went on to be well-known painters. (The pianist Simone Dinnerstein is Simon’s daughter). In those summers at Jeffersonville, there were often 10 people at the table shouting about art and politics. “Politics was the content of everything,” Miller recalled. “Art was often the medium in which it was processed.”

Her intimates recalled her charisma, her beauty, her love of dancing, and, despite her pioneering feminist spirit, her devotion to family. She married four times: First, when she was 18, there was a short union with Sidney Mintz, who would become a well-known food anthropologist. That ended a few years later, after World War II. A second tumultuous marriage, to Walter James Miller, a poet and professor at New York University, produced a daughter, Naomi May, born in 1955, as well as drama. Once, after she fled to the Chelsea Hotel, Miller hired a PI to find her.

That marriage ended in 1961. Dinnerstein also had a third, happy marriage to the ethnologist Daniel Lehrman, who died in 1972. (This marriage came with two stepdaughters, Nina and June Lehrman.) And finally, two years after the publication of The Mermaid and the Minotaur, on a trip to Kenya, she fell in love with her driver, a Kikuyu Jew named Benhazm Wachira. That marriage lasted for four years.

While The Mermaid and The Minotaur is not a memoir, it evokes these romances. The symbology of mermaid and minotaur, two hybrid human-beasts from our dreams, representing how men and women are split, tormented by ambiguities born in their infancy, unable to live freely. The book shows Dinnerstein’s avuncular brilliance and the influence of her first three husbands—the writer, the anthropologist, and the ethnologist—as well as her immersion (following several other Jewish feminists) in Gestalt psychology. During her graduate studies at Swarthmore College, Dinnerstein studied under Wolfgang Kohler, one of the leaders of Gestalt psychology, and Max Wertheimer, the Frankfurt School social theorist. She completed her Ph.D. in psychology at the New School for Social Research as a student of Solomon Asch, a prominent social psychologist, whose major work, like that of many of the Gestaltists after the Holocaust, was on conformity. She taught and researched at Rutgers for 30 years before retiring as a distinguished professor emerita.

Her fierce nonconformity, evident throughout the book, makes a memorable appearance in the final chapter of The Mermaid and the Minotaur, “At The Edge,” which contains a cri de coeur about how Hiroshima shaped her politics. She was pessimistic about the human race’s ability to survive its own meshugas.

In the 15 years between the publication of The Mermaid and the Minotaur and her death, Dinnerstein spent a good deal of time protesting the earth’s degradation. She left notes for a second book, Sentience and Survival, of which in 2019, Miller and Sarah Karl, a graduate student of Dinnerstein’s, published a fragment online.

Dinnerstein died in 1992 in a car crash. She was 69, and suffering from Alzheimer’s. “She was just at the point where they take away her license,” said her daughter Naomi Miller. She accelerated instead of pressing on the brake. “Maybe she wanted to go.” She left behind her friends, family, and comrades, one beautiful book, and the kind of life that echoes through the ages. At her memorial, a line from Swinburne was read, “from too much of living set free.” One of her colleagues played a Yiddish song on the trumpet.

Rachel Shteir, a professor at the Theatre School of DePaul University, is the author of three books, including, most recently, The Steal: A Cultural History of Shoplifting. She is working on a biography of Betty Friedan for Yale Jewish Lives.