Drakeo the Ruler Speaks to Tablet From Prison

West Coast rap god, shackled in the K-19 unit of the Men’s Central Jail in Los Angeles, a week before his murder trial

K-19 should make the ACLU declare a crusade. If you search the internet for this dubiously legal, ultramaximum-security lockup in L.A.’s downtown Men’s Central Jail, you’ll find no evidence of its existence. To call it a soul-crushing gulag is an insult to soul-crushing gulags. Shortly before voting last June to demolish this tomb, County Supervisor Janice Hahn called the Men’s Central Jail “a decrepit, outdated facility inconsistent with human values and basic decency. It puts both our inmates and our sheriff’s deputies at risk.”

This dungeon block of a half-dozen cells is where Drakeo the Ruler, the most innovative West Coast rap stylist since Snoop Dogg, awaits his late May trial on charges of first-degree murder, attempted murder, and several counts of conspiracy to commit murder. “I’m shackled up right now. I’m never not chained up,” Drakeo said recently during one of his few weekly allotted hours of phone time.

Our connection is scratchy and muffled, punctuated by automated reminders that everything we say is being recorded. Nearby in the Men’s Central Jail is the notorious K-10, a restrictive housing unit better known as “High Power,” the full-time sepulcher for several hundred of the most savage gangsters, celebrity casualties, and serial killers to haunt the streets of Los Angeles: everyone from Suge Knight to the Grim Sleeper. People know and fear K-10. The Los Angeles Times has reported exposés on its debilitating psychological impact. But K-19 is where they send you when they want to roast your sanity to cinders.

“I only have one hand free; my waist is chained too,” Drakeo continued. “When they take us all to the shower, the guards leave us soaking wet for two hours. We’ll be like ‘we’re ready to go back,’ and they’ll be like ‘oh, yeah?’ Then they just keep walking.”

After this call dropped, the guards steered the South-Central native to his cell, a dim cage scarcely big enough to stand up, sit down, and sleep. It’s adorned with inspirational fan letters and old pictures. These, he said, help him remember what it was like when he was free. No visits are allowed. His lawyer has successfully petitioned the judge to strike down some of these restrictions as unconstitutional, as they severely impaired his right to counsel. Even sunlight is a luxury: 60 minutes a week on Fridays, during which prisoners remain isolated and wrapped in iron ropes.

“This is all motivated by two things: the fact that I’m a rapper and the fact that I’m a black rapper,” Drakeo said, repeating the conclusions that he’s continually drawn since first being incarcerated in January of 2018. “When they brought me into the station, [the deputies] were playing my videos, rapping my lyrics back at me, and bragging about the other rappers that they’d sent away. It’s targeted harassment.”

Until a few months ago, Drakeo had been housed in a regular dormitory, but when an Instagram post on his account cursed the two detectives assembling the case against him, he was tossed into K-19. Only in court did he and his attorneys discover that the punishment was due to a few fans emptily threatening the detectives in the comments section. “How am I supposed to control what my fans say!?” Drakeo said, his voice rising in disbelief. “I don’t even have access to my Instagram to post anything. And the crazy part is, these detectives are trying to call me a part-time rapper and a full-time gang leader. How can I be a part-time rapper and be on the cover of the L.A. Times and have thousands of fans coming to my defense? Which one is it?”

For most of the past 18 months, we’ve talked once or twice a week, with the conversations assuming a similar pattern. We talk about random music news that he mostly misses or bullshit songs on the radio that he mostly hates. For the most part, we talk about his case. According to Drakeo and his attorney, that case will hinge largely on attempts to hold the 25-year-old rapper’s lyrics against him in a courtroom—even though his songs fall squarely within the pistols-and-palm-trees tradition of West Coast gangsta rap. By manipulating racially biased gang injunction laws and mandatory sentencing enhancements, prosecutors have branded his crew, the Stinc Team, as a gang—ludicrously claiming that his songs are recruiting advertisements. Nearly the entirety of Drakeo’s crew—his close friends, brother, and several other rap partners—are being held on charges ranging from murder to commercial burglary to vandalism.

“None of this makes any sense!” Drakeo said, referring to the charges that have landed him here. “Why would I show up to a party to kill a rapper that I don’t want to kill, who wasn’t even on the flyer of the party?? We follow each other on Instagram. If I had wanted to find out where he was, I could’ve found out where he was at any time.”

The rapper that Drakeo was allegedly trying to murder, RJ, has made multiple public statements that he doesn’t believe the conspiracy accusations against Drakeo. More recently, he’s DM’d him to ask about his well-being and even shouted out Drakeo videos on Instagram. Of course, the #FreeDrakeo hashtag is all over Twitter and Instagram, but there is the gnawing sense that someone should be screaming to whomever will listen that this is absolute lunacy.

According to Drakeo, his mother’s former employer, the Los Angeles Unified School District, received letters from the police intimating that she was part of a conspiracy to commit murder. Drakeo also claims that one of his co-defendant’s children was even placed in foster care because the infant made a blink-if-you-missed it cameo in the video for a song called “Shoot a Baby.” All babies emerged from the shoot unscathed, but the prosecutors cynically understand how easily lines between art, irony, and real life can be blurred. By painting Drakeo and the Stinc Team as infanticide-loving terrorists, it’s a much easier cognitive leap to convince 12 jurors that they’re responsible for an actual gang killing, especially when the courthouse is in Compton.

Americans like to imagine our criminal justice system as a fair-if-imperfect rigging of scales and balances, where thankless bureaucrats attempt to affect some rough semblance of righteousness. Instead, the American court system is just like everything else in this country: governed by money, tarred by prejudice, and moved by the casual perjuries of cops, judges, and prosecutors who get away with what they can until they’re caught. They’re rarely caught. It’s easy to figure out how Philadelphia rap star’s Meek Mill’s judge was under FBI investigation for a series of improprieties that included asking him to shout her out in a song. It’s why hundreds of black artists, famous and anonymous, have had their music used against them as weapons in courtrooms.

***

It starts in the Hundreds section of South-Central, a maze of low-slung stucco homes with steel bars on the windows, where Darrell Caldwell spent most of his adolescence. There, he acquired a juvenile crime record and eventually graduated from a continuation school on Central Avenue, the ancestral vein of L.A’s cool jazz scene. His mom was a preschool teacher of Afro-Puerto Rican descent; his dad was never around. By his late teens, he’d already cultivated a reputation as a legendary “flocker” (L.A. slang for robbing homes), and a taste for crashing foreign luxury vehicles. In search of clean money, he started rapping and within a year scored a viral Soundcloud hit that attracted the attention of DJ Mustard, the king-making L.A. producer, who released it officially and offered Drakeo the only signal boost he’d ever need.

By the summer of 2016, Drakeo was the hottest young rapper on the streets of L.A. Without radio airplay, a major label deal, or even a manager, he’d conjured his own pharmacy-slurred cosmology; you could glimpse him on Normandie, a platinum-dripping phantom swerving in a Rolls Royce Phantom, creating his own wind-talker dialect, rife with allusions to Judas Iscariot and Sideshow Bob. In his idiolect, extension clips on rifles became “Shenaynays” or “Pippi Longstockings,” slang coined to honor the long-haired characters from Martin and Astrid Lindgren.

His name came not from the semi-automatic weapon or the Canadian rapping turtleneck, but from the ancient Athenian lawgiver, who bequeathed us the adjective “Draconian.” He named himself “Mr. Moseley,” a double-entendre that either describes his code for sipping lean or an allusion to Walter Mosley, the legendary hard-boiled South-Central crime writer. He branded his subgenre “nervous music,” which was explained as the tense anxiety-wracked anthems you write when you’re pushing a $100,000 sedan knowing that your rivals will spray you with lead if they catch you slipping at a red light.

If L.A. gangsta rap was still nationally known for khakis, chronic, and ’64 Chevys, Drakeo rapped about rolling in a Bentley and “mudwalking” through Neiman Marcus, a .40-caliber bulging from his hip, no belt needed. Somewhere between E-40 and Ghostface Killah, his sound was distinctly homegrown and singular, as if it had materialized from a velvet codeine fog. As ratchet, a minimalist strip-club bounce, fell out of vogue, Drakeo reimagined the sound as something full of sinister, chrome-plated menace. His flow was a hallucinatory mumble, scraping sideways against the beat, syllables oozing like a rattlesnake strangling its prey. It was Philip Marlowe in Maison Margielas and a Maserati.

The sky was the limit until it caved in. In early 2017, the police invaded a condominium near LAX where the Stinc Team shot several of their videos. They discovered a stash of guns that they claimed belonged to Drakeo. He maintains that his name wasn’t on the lease of the apartment, nor was he even in the unit during the raid. Nonetheless, he was charged with six counts of illegal possession of firearms by a felon, a charge that drew him a year-long sentence in the county jail. As he languished behind bars, his stock rose even while his trademark rhyme style was mimicked by a raft of imitators.

Upon his release in late 2017, Drakeo recorded Cold Devil, an immediate contender for best L.A. rap album of the decade. Most songs were written in jail, where he infamously mugged on Instagram Live during his final month of lockup. Within a few weeks of his freedom, he was already playing sold-out shows throughout the Southland, receiving breathless reviews on Fader and Pitchfork, and was trumpeted as the future of L.A. rap on the front page of the Sunday Los Angeles Times Calendar section.

There was only one recurring problem. Just after New Year’s Day, Drakeo was cruising through South-Central when a police cruiser began following him. He pulled into a liquor store to make a purchase. When he came out, the police threw him against his car, hands up, as they exhaustively searched his person and vehicle. They found nothing. Then they decided to search the liquor store, discovering a handgun on one of the shelves. Drakeo denied culpability, but was hauled into the Monterey Park Sheriff’s Department and booked back in county on charges of illegal firearms possession.

Two days after the Times story ran, the authorities brought him before the court and charged him with multiple counts of murder, dating back to a 2016 incident. Several days later, police officers in San Francisco burst into the hotel rooms of members of the Stinc Team, including his brother Ralfy the Plug, while they were touring with breakout L.A. rap sensations Shoreline Mafia. No one has returned home since.

***

Almost everything about the case remains in doubt, save for one unassailable fact: A 24-year old alleged Inglewood Blood named Davion Gregory was murdered on the night of Dec. 10, 2016. According to the district attorney, Drakeo, a man named Jaiden Boyd, and Mikell Buchanan (a Stinc Team member who rapped under the name Kellz) met up that evening at 11622 Avalon Blvd. in South-Central, where they claim that Drakeo supplied guns to Buchanan and Boyd for the purpose of killing a popular South-Central rap rival named RJ.

For most of that fall, Drakeo had been publicly feuding with RJ, then one of DJ Mustard’s artists. It culminated with the “Flex Freestyle,” where Drakeo hijacked the beat for one of RJ’s hits and set it aflame. One of the most caustic and hilarious disses in recent memory, Drakeo clowned RJ’s haircut and advanced age, and boasted about driving around with him tied up in the trunk. Needless to say, none of this was a description of an actual crime; it was a hysterical and ominous slab of beef rap that fits into a historical continuum dating back to the dozens and South Bronx park routines.

Yet the district attorney is now attempting to use Drakeo’s lyrics as evidence against him in court, an unconscionable ploy to con naïve jurors who believe all rap is autobiography. In the district attorney’s rendering of that night, Drakeo, Boyd, and Buchanan went to a “Naughty or Nice Pajama Jam” at a warehouse party in Carson to lie in wait for RJ. However, the DA claims that RJ never showed up, and around 11:30 p.m. Buchanan instead killed Gregory, wounding two others in the process. According to police, the getaway car was a red Mercedes allegedly owned by Drakeo. According to Drakeo, his Mercedes is black.

By everyone’s account, Drakeo wasn’t the triggerman, but the police nonetheless won a first-degree murder indictment—alongside several charges of attempted murder (two other people were wounded by the gunfire). To compound the severity, they filed a special circumstances case that would ensure Drakeo’s life imprisonment.

According to California state law, Drakeo should already be a free man. On New Year’s Day, a new law was enacted that makes it almost impossible to convict an accomplice for murder unless they actively participated in the plot to kill. Even though the DA isn’t alleging that Drakeo wanted anyone to shoot Gregory, they’re claiming that since Drakeo conspired to kill RJ, he’s by default also guilty of plotting to murder anyone that he and his companions randomly came across that night. According to Drakeo’s attorney, Frank Duncan, there are no eyewitnesses to place Drakeo at the scene of the crime. He claims that the prosecution’s case is almost entirely built upon testimony from jailhouse informants seeking reduced sentences.

What’s clear from the above is that the DA is expending a staggering amount of energy and resources for what would otherwise be an ordinary gang killing in South L. A. Drakeo believes it’s solely due to two sheriff’s deputies, Richard Biddle and Francis Hardiman, who have their scopes set specifically on the Stinc Team. Biddle was the lead investigator in the Suge Knight criminal cases.

While Drakeo awaits trial, he happens to be languishing in the same exact cell that until recently housed Suge.

***

You hear the chains rattling first. Behind a heavy wooden door, a thousand pounds of steel clank, tied tight across human flesh, dragged across the filthy tile floors like an antebellum horror story. An unfriendly voice screams “WALK!!!” And one by one, it goes. A tattooed prisoner in an orange jumpsuit shuffles into the court room, squinting in the shrill artificial light, craning his neck to see if any family members came today.

“WALK!”

More cadaverous thumps from behind closed doors. Another inmate slinks in, eyes gravely lowered, metal asphyxiating waists and wrists. The men, all African American, mumble asides to each other while waiting in a pen separating the accused from the free. Until finally, an entire rap crew has been assembled.

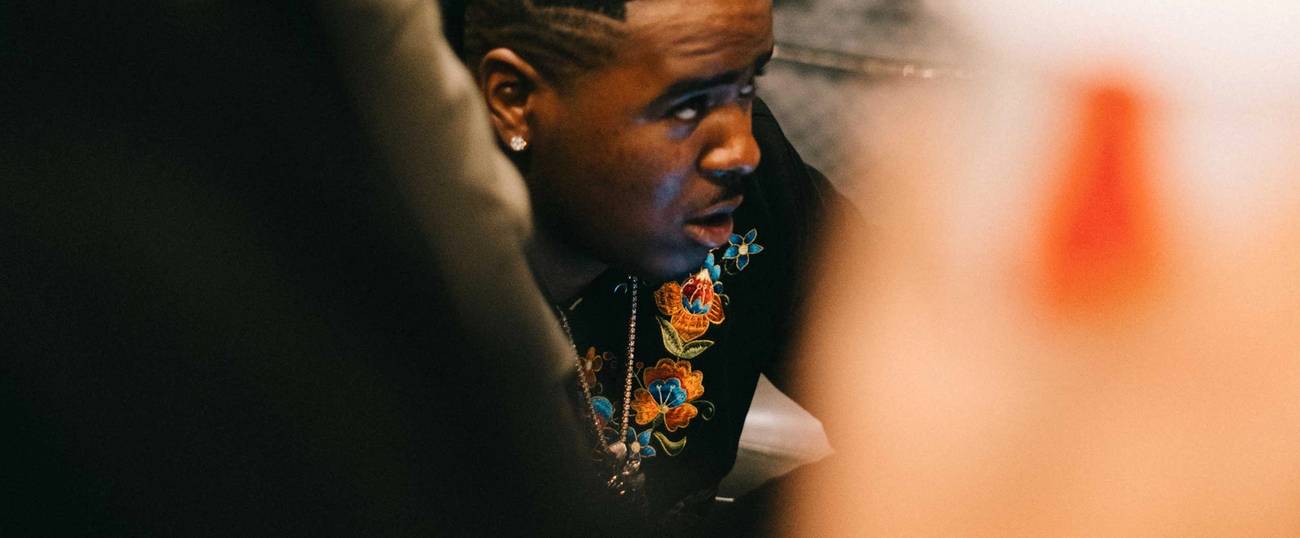

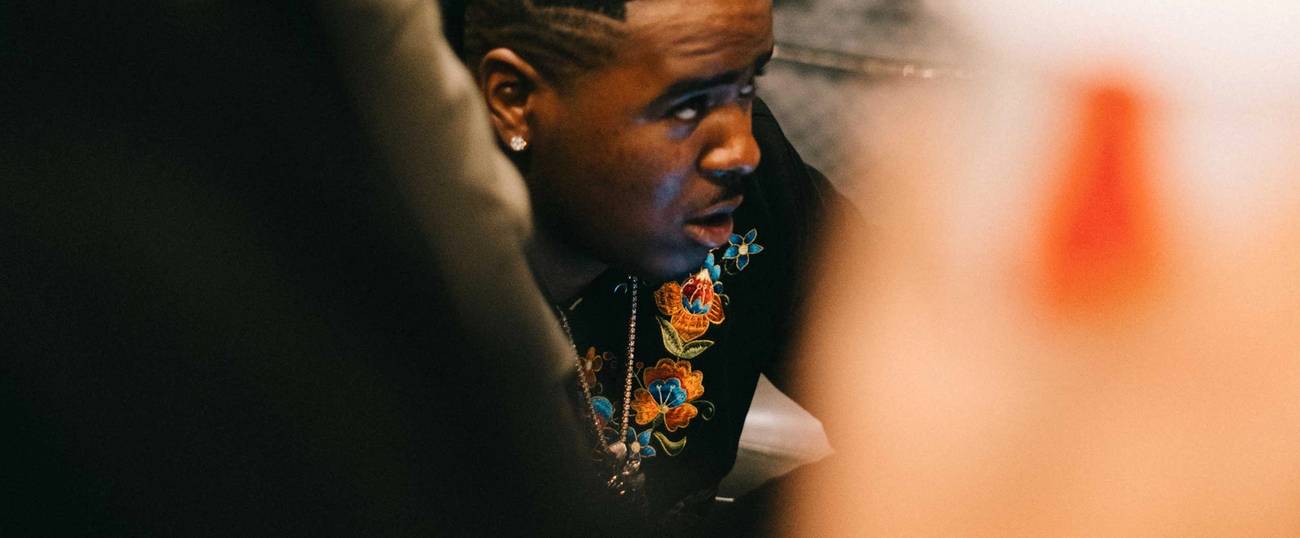

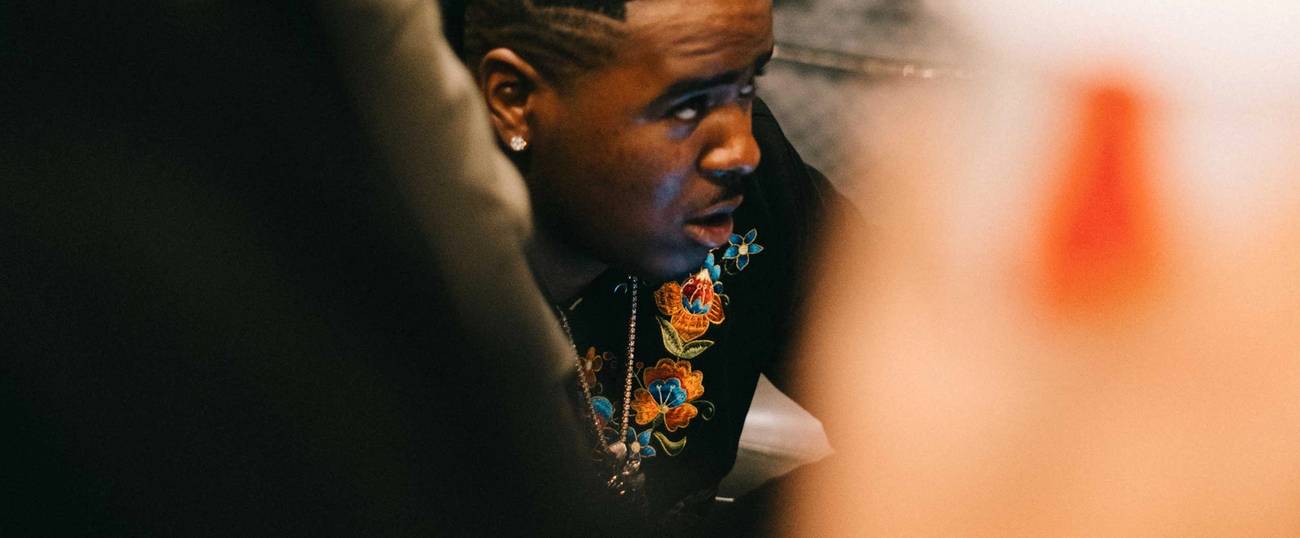

It was Drakeo’s penultimate pretrial hearing in late March. He was one of the last to enter this high-security courtroom, where they search you twice before entering and no cellphones are allowed.

Drakeo’s demeanor was starkly different from the other co-defendants. There’s the star wattage you’d expect from any famous performer, but Drakeo is different even from those who are professionally different. When he was free, he and his crew didn’t greet each other with handshakes, hugs, or daps and pounds; they linked pinkies. In court, he’s so confident that it almost feels contrived. He’s completely manacled, but carries himself as though this entire thing is a farce; you know it, he knows it, and the judge damn well ought to know it. When the prosecutors say anything, he rolls his eyes, cackles, cockily tilts his head and smirks with “can you believe this bullshit?” knowingness.

Neither Hardiman nor Biddle appeared in court for Drakeo’s pretrial hearing that late March afternoon, but they showed up at an earlier court date this February. Drakeo describes them as looking like Chief Wiggum and Mr. Burns from The Simpsons; they’re shaped like bald pink bullets and straight out of a Dragnet daydream.

As for the scheduled hearings that afternoon, they were mostly concerned with perfunctory motions and bureaucratic details. The lawyers for the other defendants kept asking for delays, but Drakeo’s team adamantly petitioned for the trial to start as soon as possible. The judge, a black woman named Laura Walton seemed sharp and impartial, opting not to reprimand Drakeo when he spoke.

The trial date was finally set at May 20. For someone whose life is on the line, Drakeo seemed mostly in good spirits, laughing constantly, joking with his co-defendants, so supremely confident-seeming that you’d never believe that he was the man who invented nervous music. When it was time to go, he nodded and flashed a conqueror’s smile at his friends and family in the courtroom, then clanked out.

An hour after court adjourned, Drakeo called me. On pretrial days, there’s a several-hour window between the hearings and when they haul the prisoners back to the Men’s Central Jail, which means that Drakeo gets a little extra phone time. Whenever I ask how things are going, Drakeo inevitably tells me that it’s regular. When Drakeo was on the streets, regular meant wearing designer clothes draped with a quarter million dollars of jewelry and driving around in something that you usually only see valet-parked in front of The Ivy. In here, regular means that each day is almost identical to the one that preceded it. A slow drip torture, a grayscale Groundhog Day where your neighbors are a cop killer and a Mexican Mafia capo.

“Nobody gives a fuck and that’s why I be tripping,” Drakeo said. “Don’t get me wrong; a lot of people go to court for me, but nobody else can see what’s going on. There’s no evidence there that says that I did nothing. Nothing! There’s even people who are saying that I had nothing to do with it, but the [cops] are just trying to make up this crazy story about me.”

If there are any signs of nerves, Drakeo has never shown them. He says he has good feelings about the upcoming trial, due to the flimsiness of the case. Of course, there is the latent maddening frustration of spending years of his life in this cage. No matter what, the detectives will see no repercussions. Even if they lose the case, they will have won by halting his momentum right as he was ascending to national superstardom. If Drakeo wins, he will still have spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on legal fees, not to mention that he is being deprived of the millions that he could’ve made from recording and touring. All the streaming money that he’s currently raking in has been funneled right back into fighting his case.

Drakeo prefers to think about the future. What he plans to do when he gets out. Three albums in three months, so he can finally start making real money again.

He’s been intently studying the Neiman Marcus catalog, deliberating what outfits he’s going to buy when he comes home. Most of his daydreams concern cars, which is unsurprising for someone who nicknamed himself “the foreign whip crasher.”

“At first, I wanted to get a [Mercedes], but then I seen this [Bentley] Mulsanne and that new Lambo,” Drakeo said eagerly. “I didn’t want to get no Lambo with the doors like that, but the Huaracan changed them. The thing is I wanted a Bentley but every rap nigga got a Bentley, so maybe I’ll just get the McLaren, but not with those bullshit features …”

He was about to go on, but in the background, there was garbled unintelligible yelling and the harsh clunk of more chains rattling. It was time for him to go back to K-19. As he started to say his goodbye, someone suddenly cut the call off.

Jeff Weiss, the editor of Passion of the Weiss, is a regular contributor to The Washington Post, the LA Times, and Pitchfork. His Twitter feed is @Passionweiss.