Drawing Inspiration

In a searching memoir, a daughter revisits her father’s deceptions

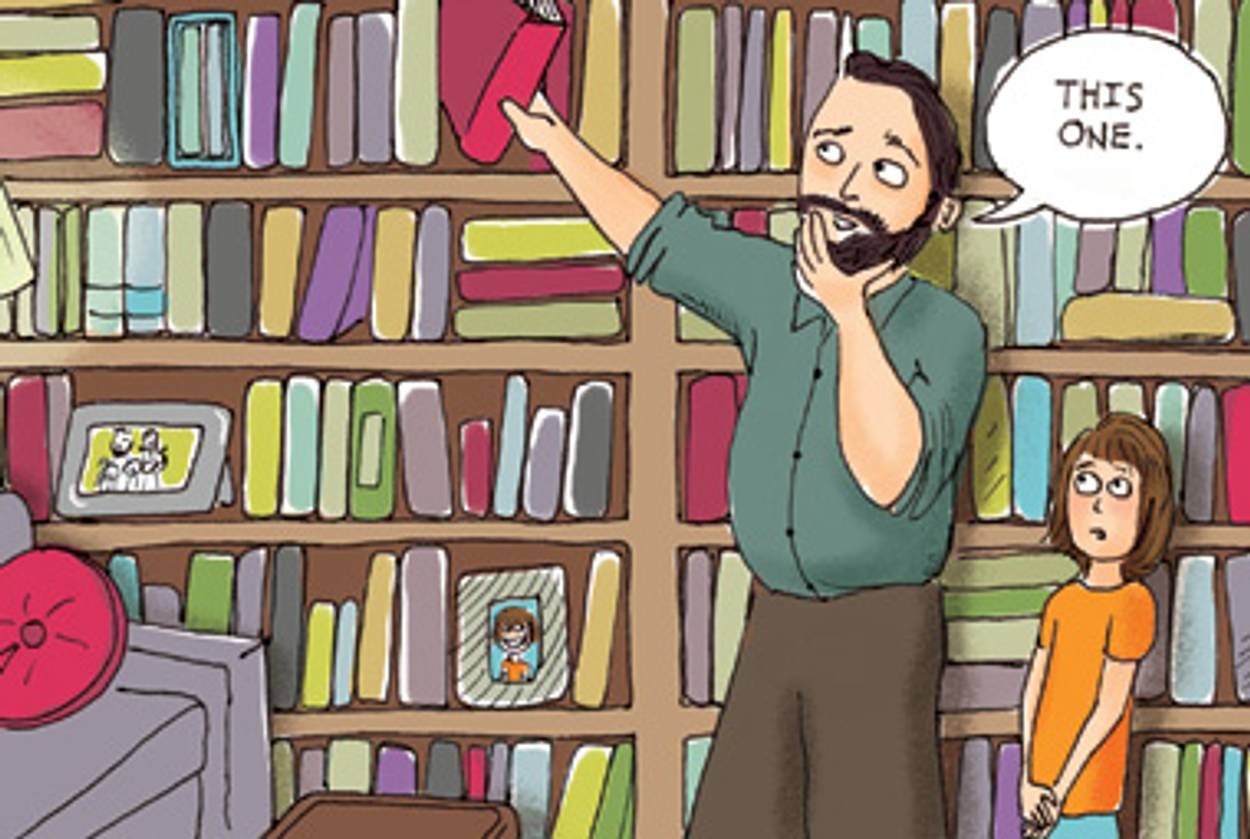

When journalist Laurie Sandell was a child, she started drawing cartoons of the people in her life, but in panel after panel, her father’s likeness was dominant, dwarfing all else.

“Obviously I really looked up to him,” she said recently on the phone from a friend’s beach house. “But in a way I was very sharply seeing the truth in my childhood cartoons.” Whether because of his angry outbursts or his compelling, if hyperbolic, stories of duels and foreign adventure, he was her focal point.

Back then, she’d leave these works for her father to find on the hallway credenza, and then wait around the corner for his approving laughter—a sound she hasn’t heard now in some time. Except for pleasantries at Passover and other holiday gatherings, Sandell and her father stopped speaking in 2003, when she published an anonymous article in Esquire that kicked off with the question, “What would you do if, at thirty-one, you realized that every single thing your father ever told you was a lie?”

Her answer was to put that realization process into a graphic memoir. The Impostor’s Daughter, out this week from Little, Brown, tells Sandell’s story of uncovering her father’s various deceptions—from tall tales of impossibly heroic feats in Vietnam to credit card fraud to affairs—and depicts, too, her own doomed entanglements with romantic partners, drug dependency, and finally, rehab.

The book, she said, is “debunking the myth of my father,” the son of European Jews who sent their boy to Buenos Aires in order to spare him the fate suffered by some relatives during World War II. Years later, his father wound up killing himself before Sandell, now 38 and living in Brooklyn, was born; she didn’t meet her paternal grandmother until 1980, the last year of the woman’s life. (“She didn’t speak a word of English, so I communicated with her by crocheting hats together.”)

Her father came, at age 19, to the United States where he met Laurie’s mother—an honest, loyal schoolteacher. They lived in Stockton, California (her father taught economics) until Laurie was 8 and then moved to the suburbs of New York, where he soon left teaching and took up one secretive (and unsuccessful) get-rich scheme after another.

Trying to sort fact from fiction in her father’s biography, Sandell found that writing a book about him was tough. There was “this whole layer of having to wrestle with what this meant about my relationship with my father, and who he really was, and was this going to be the end of our relationship. I was having a hard time getting the distance I needed,” she said. A contributing writer at Glamour where she interviews celebrities, Sandell drew occasional cartoons for the magazine as well as for friends’ birthday cards. “I was able to cartoon so honestly about my dad when I was a kid, I thought, what if I start telling this story that way? Will that allow me to almost feel safer?”

It did, enough to allow her to go ahead with a comprehensive unmasking process, both of her father and her self. She is candid in portraying her itinerant post-college years, “an exercise in self-destruction,” she writes in the book. “I told many lies. I was willing to be anything, try anything, as long as it didn’t resemble the life I was living before.”

In that period, Sandell lived in the old, ramshackle West Jerusalem neighborhood of Nachlaot, where Orthodox residents live cheek by jowl with artists and hipsters. She spent her time studying Hebrew, waitressing, and partying. Then, on a whim, she left a lover and moved to Japan, where she worked as a hostess, (“a sort of modern-day geisha,” she writes) and then as a striptease worker.

“It was a very unsettled period of my life,” she said. “And there’s no question that I was mirroring my father. I think that continued well into my 30s. Even when I started working for Glamour—that was mirroring my father on some level because he always talked about his life and how he navigated the world. I was trying on an identity that would please my father. It’s a bit of a stretch, and it’s that armchair psychology thing, but I feel confident that’s what was going on. Being raised by my father, learning to be a chameleon—that is something he gave me that I was able to use.”

Like any child, Sandell has complicated feelings about her family. “I ask myself if I love him. I still do,” she said. But “growing up in a family where lies and denials were the order of the day—that was quite damaging, and led to intimacy issues with me, addiction, the loss of a sense of self and a loss of identity. On a certain level, it’s important for me to tell my truth.”

Sara Ivry is the host of Vox Tablet, Tablet Magazine’s weekly podcast. Follow her on Twitter @saraivry.

Sara Ivry is the host of Vox Tablet, Tablet Magazine’s weekly podcast. Follow her on Twitter@saraivry.