Dressing for Paradise

Was Frida Kahlo Jewish, and does it matter? A blockbuster show at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum brings the Mexican artist’s contradictions to life.

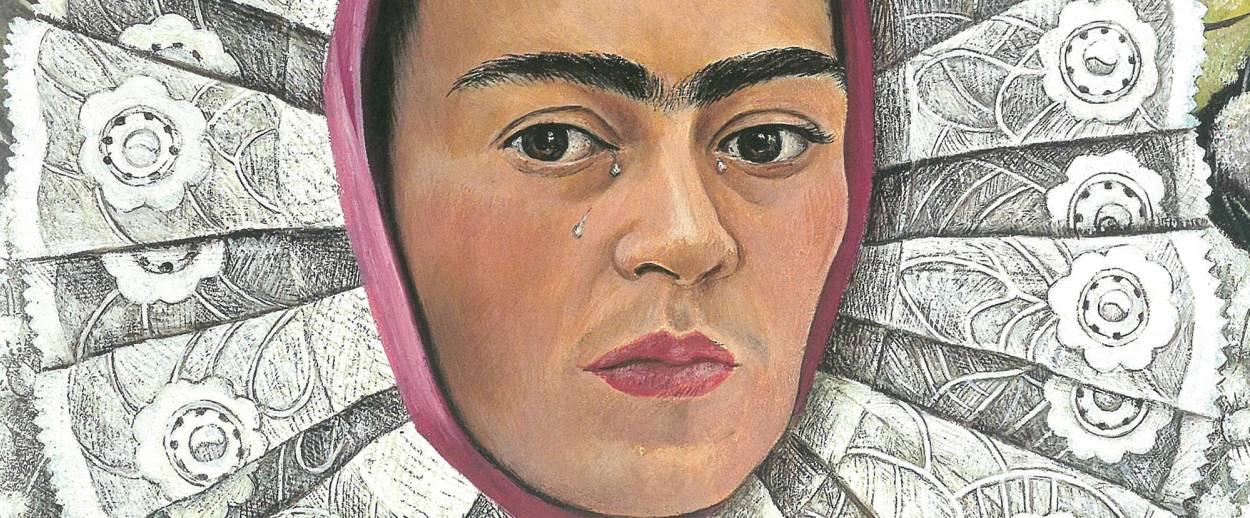

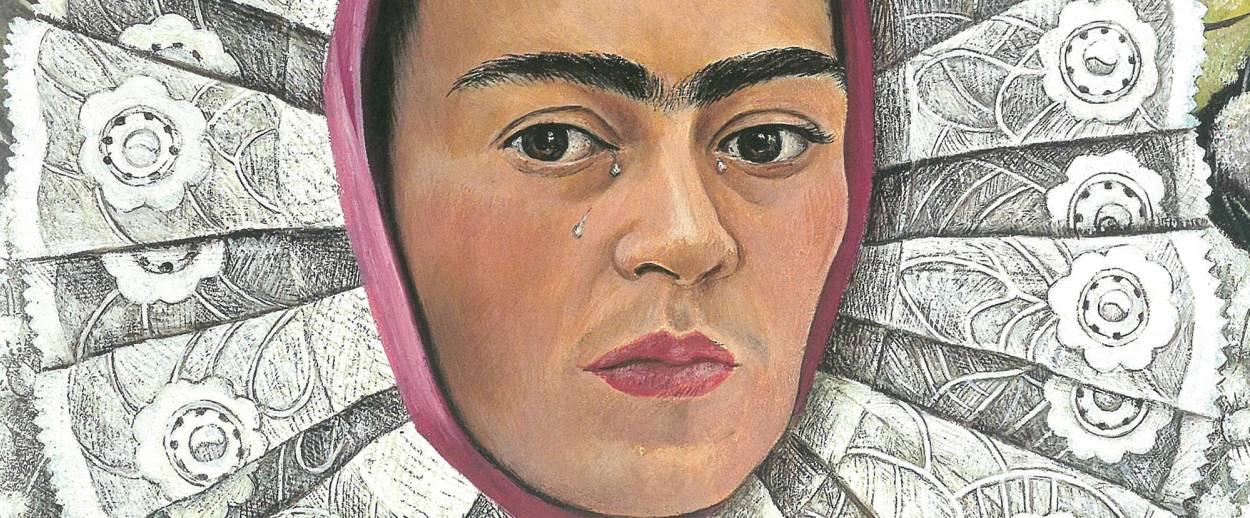

“A manner of dressing for paradise, of preparing for death.” That’s how Carlos Fuentes described Frida Kahlo’s wardrobe, the sumptuous grandeur of her satin and velvet skirts, fringed rebozos (shawls), embroidered huipils (tunics), the luster of her rattling bracelets, the weight of her massive beads, the flamboyant rings adorning her fingers and thumbs. There were also the breathtaking resplandors, flowered lace headdresses, which she collected and wore in the 1940s in self-portraits showing tears rolling down her cheeks. With a pleated ruffle surrounding her face like the petals of a flower, she was a tragic bride, a pious nun, an Aztec goddess, and the incarnation of Mexico’s ancient sorrows and tragic betrayals.

All of Mexico knew the drama of her life: When she was 6 years old, she was afflicted with polio, which withered her leg. When she was 18, a streetcar collided with the bus she was riding, breaking her collarbone, spine, ribs, and pelvis, shattering her right leg and crushing her foot. The frame of an iron hand rail impaled her abdomen and pierced into the vagina. When she was 22, dressed in clothes borrowed from a maid, she married Diego Rivera, the most famous artist in Mexico and arguably the Americas, a champion of the poor, a Communist who had lived in Paris and the Soviet Union. Twenty years her senior, Rivera was already twice married, weighed over 300 pounds, and had the reputation of a rooster, going after anyone with “the wherewithal under its skirt,” as their friend Dr. Leo Eloesser put it.

What followed were infidelities, lost pregnancies, divorce, remarriage, excruciating hospitalizations, and surgeries that included the amputation of her gangrenous right leg a year before she died, perhaps from a pulmonary embolism or perhaps from an overdose of painkillers. Frida Kahlo was mexicanidad; she drew upon it for her paintings and costumes and she surrounded herself with its essence in her home, which contained tens of thousands of objects, ranging from scowling Olmec figures to papier-mâché Judas skeletons, which she occasionally dressed in her shawls and underskirts. It was also said she was Jewish. But was she?

Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up, on view through Nov. 18 at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, is both a sold-out blockbuster and a surprisingly somber reconsideration of the artist and her turbulence. It reunites a collection of paintings and drawings, many self-portraits, with about 200 intimate objects on loan from the Museo Frida Kahlo, also known as La Casa Azul, the Blue House, the home where Kahlo spent most of her life, in the Coyoacán neighborhood on the outskirts of Mexico City. The exhibit includes an extensive collection of photographs as well as film documenting Mexico at the turn of the 20th century, her family and childhood, the years she and Rivera socialized with world celebrities, their relationship with Trotsky (who was their guest in Casa Azul from 1937 to 1939 and with whom she had an adulterous affair), as well as the harrowing final years of physical and mental agony. It demonstrates the boundarylessness of her style, evident in everything she did, from the daily ceremony of putting on her clothes, layer by layer, to amusing herself with her menagerie of parrots and spider monkeys, an osprey named Gertrudis Caca Blanca (Gertrude White Shit), her little deer, Granizo, as well as her beloved Señor Xolotl, the Mexican hairless dog whom she depicted tenderly curled on a bed of soft leaves in her startlingly poetic painting The Love Embrace of the Universe.

The show also reminds us that appearances can be deceiving. Las Apariencias Engañan, she inscribed the bottom of an undated self-portrait, a drawing in charcoal and colored pencil showing her half-corseted torso with an architectural column positioned at her spine and a triangular swatch of pubic hair beneath a transparent, pulled-away skirt. Kahlo was well aware that costume could conceal many things, from mercurial sexuality to a traumatized body, and she meticulously drew her withered right foot as well as a left leg decorated with butterflies. “Feet,” she wrote in her diary, “what do I need them for, if I have wings to fly.”

Like tomb objects, the costumes and an immense trove of idiosyncratic personal items—her prosthetic leg fitted with a red leather boot decorated with Chinese dragons and bells, orthopedic devices, medicine vials, liver pills, face cream, nail polish, and perfume bottles (including a Shalimar flask with the famous fan-shaped stopper)—remained, just as they were left, some in a bathtub or resting against a wall, for 50 years after Kahlo died in La Casa Azul. The rooms where they were kept, a bathroom and storage area with trunks, wooden wardrobes, dressers, and boxes, were unlocked in 2004 when the job of cataloguing, cleaning, and analyzing began. Following on that work, conservators for the current show, to give one example, recently noticed a jade stone with a splash of green paint, indicating that Kahlo may have been matching the stone’s color against paint on her paintbrush while she was painting herself wearing the string of jade beads.

This is the first occasion the objects have traveled outside Mexico and the V&A has pulled out all the stops. Using vintage photographs, 3D rendering, and 3D printing, they created exhibition mannequins matching Kahlo’s height and silhouette and then developed plaster masks of her head and face, as they say in the video, “to evoke Frida Kahlo without being pastiche.” Leaving gaps in the irregular surfaces on the arms and necks, they’ve managed to suggest her broken body and to approximate the weathered quality of the faces in her paintings.

You may or may not like the way the installation produces the sensation of a pilgrimage with painted replicas of the artist’s four-poster bed used as vitrines to display her medicines, anatomy books, painted corsets, as well as cosmetics, sewing box, and cat-eye sunglasses. But the small retablos, inscribed devotional paintings, representing tragedies averted, are a delight. Although Kahlo rejected the Catholicism of her upbringing—she wrote “IDIOT!” on the back of her First Communion photo—she collected hundreds of these vernacular-style votives, especially prizing illustrations of gruesome accidents. You can see the link between the graphic narratives in the ex-votos to her early narrative paintings, such as Portrait on the Border Between Mexico and the United States, where she used the same technique of oil on tin to tell the story of her life in America represented by machinery, skyscrapers, and smokestacks, and her homesickness for Mexico with its ancient ruins and rooted fertility.

Costumes form the centerpiece of the show and they tell the story of astonishing imagination. Kahlo began dressing in Tehuana style at the time of her marriage and her wardrobe helped her craft a unique identity so she could stand her ground beside Rivera, who was already legendary. When they were living in America, starting in 1930, she garnered attention for her beautifully feminine and flamboyant style. From San Francisco, she wrote home: “The gringas have liked me very much and they are impressed by the dresses and shawls that I brought with me, my jade necklaces are amazing for them and all the painters want me to pose for their portraits.”

In the exhibit you can see how Kahlo worked in the spirit of a collage artist, mixing Mexican and Guatemalan embroidered and woven work with European and Chinese fabrics, contrasting colors, patterns, and shapes with artistic originality (eventually using the garments as camouflage for the deformity of her body). The clothed mannequins can’t convey Kahlo’s youthful playfulness and intimacy, the generosity of her spirit, or her devilish side, her irreverence, the way she delighted in using offensive language, particularly in English, calling the sullen bellboy at the Barbizon Plaza “a son-of-a-bitch.” And they certainly don’t convey the even tougher Frida who was drinking a bottle of cognac a day in 1939. Rather, they present her constructed image, the exotic dignity in the photographs, particularly in the magnificent series of colored images of her made by her lover, Nickolas Muray, who worked for Vanity Fair, Vogue, and Harper’s Bazaar.

Making Her Self Up, of course, is a pun. The camera loved Frida Kahlo and she had known since childhood how to direct her gaze (sometimes confrontationally), telling her story for the photographer’s lens. You see this again in the self-portraits which become increasingly defiant and aggressive over the years as losses mounted up along with unbearable loneliness and physical suffering, while the idea of “preparing for death” was more and more on her mind. “I have enjoyed being contradictory,” she said at the end of her life.

That idea can be applied to her entire biography which had the quality of magic realism, every detail changeable and changing, starting from the year of her birth, which shifted from 1907 to 1910 in order to coordinate with the beginning of the Mexican Revolution. A great deal has been written about the fluidity of Kahlo’s sexuality. It’s well documented that she had affairs with both women and men. You can see from family photographs taken in 1927, that for a while after the bus accident she wore her hair cropped short and dressed convincingly like a boy. In her later self-portraits, she audaciously painted in the mannish facial hair above her lip and between her brows.

***

Did Kahlo make up a Jewish identity? In a famous early painting, My Grandparents, My Parents and I, now owned by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, she painted a variant of a family tree. On the one side, high over the Mexican mountains, you see her dark-skinned maternal grandfather, a Mexican Indian from Michoacán, and her maternal grandmother who was a gachupina, descended from a Spanish soldier. On the other side, her European grandparents are depicted far over the sea: Henriette Kessler Kaufmann Kahlo has something of Frida’s unibrow and Jacob Heinrich Kahlo is distinguished by fiery eyes and a broad, drooping mustache.

Kahlo’s mother was so devoutly Catholic that she and her sisters sat on a reserved bench in Coyoacán’s Church of San Juan Bautista, but her father, Guillermo Kahlo, was said to be a nonobservant Jew. Not much is known about Guillermo, a quiet man, who emigrated to Mexico in 1890 and worked for a while at the Loeb Crystal Company before becoming a photographer. He loved German philosophy and literature, German music, his German piano, and had a fine portrait of Schopenhauer. Occasionally, he played chess with a friend and his Spanish was inflected by his German accent. He had monthly epileptic seizures caused by a fall as a young man. Like the itinerant photographer in Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, he traveled with his camera throughout the republic, taking inventory of Mexico’s architectural heritage on hundreds of glass plates. Perhaps it was a Jewish sense of humor showing through when he said he didn’t like to photograph people because he didn’t want “to improve what God had made ugly.”

Though the V&A exhibit has skirted the controversy, a 2014 book published in Germany has disputed Kahlo’s Jewish heritage and until more genealogical research is done, the truth hangs in the balance. According to Kahlo family legend, Guillermo Kahlo came to Mexico from Baden-Baden, but his parents were originally from the city of Arad in Austria-Hungary (now Romania). His mother’s family owned a jewelry business which his father eventually took over.

There are other clues. On the back of the photo of her paternal grandmother, Frida inscribed: “My father’s mother (a German Jew).” At a restricted hotel in Detroit in 1931, both Frida and Rivera claimed to have “Jewish blood,” causing the embarrassed staff to lower the room rate. Many of their friends were Jewish—Dr. Leo Eloesser, Gisèle Freund, Ella and Bertram Wolfe, Lucienne and Suzanne Bloch, Anita Brenner, and Nickolas Muray. Kahlo and Rivera also socialized with a circle of Jewish (and Yiddish-speaking) intellectuals in Mexico City in the 1930s and 1940s. In 1936 Rivera illustrated their friend Isaac Berliner’s book of poems, La Ciudad de los Palacios (The City of Palaces), with bold and expressive linocut plates. Written in Yiddish, the book reflects a surreal journey from Jewish Europe to Mexico City, weaving together tragedies of the diaspora with Mexican suffering. Kahlo, who, as Fuentes said, was preparing for paradise, must have felt compassion for that tangle of troubles. Beneath the sweeping costumes, her whole body was wracked with pain. The verification of Jewish identity certainly wouldn’t have mattered.

***

Read more of Frances Brent’s art criticism in Tablet magazine here.

Frances Brent’s most recent book is The Lost Cellos of Lev Aronson.

Frances Brent’s most recent book is The Lost Cellos of Lev Aronson.