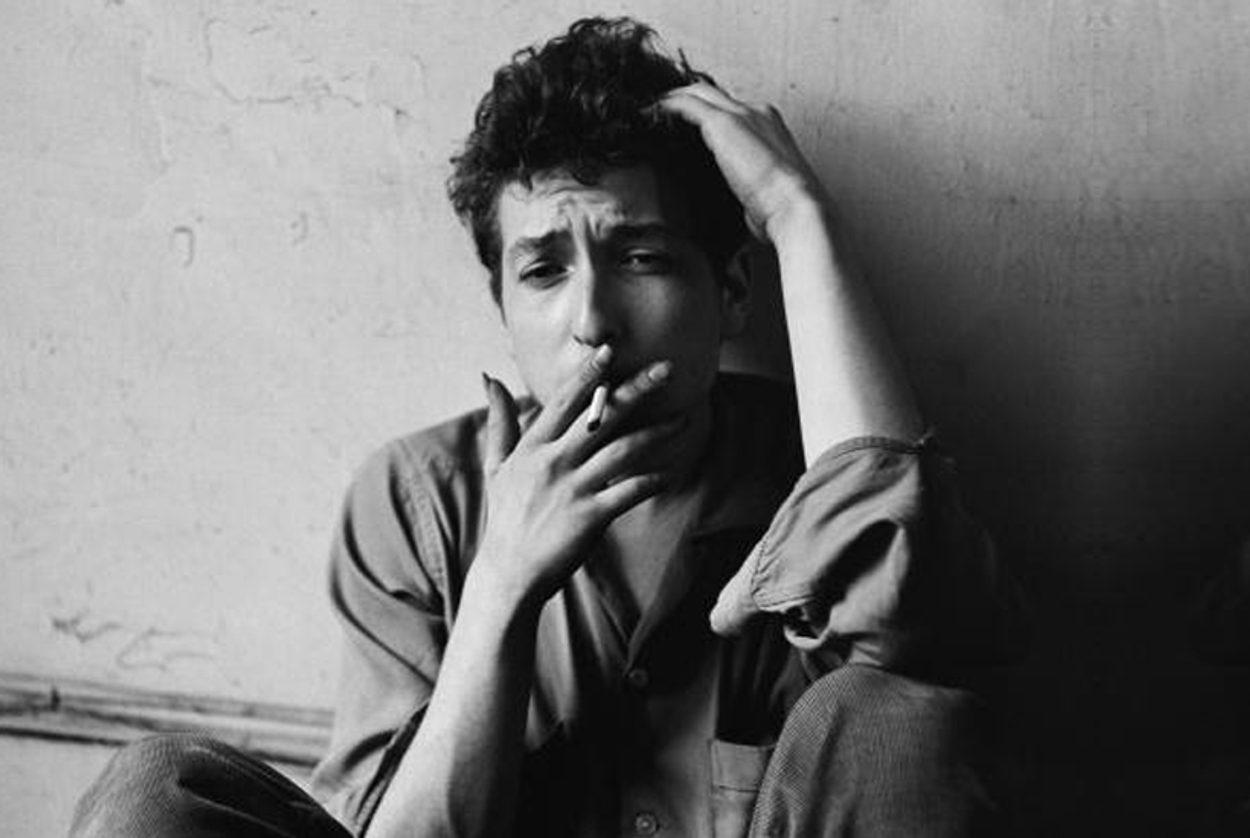

Bob Dylan, Existential Hero

The Basement Tapes, finally released after 47 years, show yet another side of the bard

There are two major ways to be wrong about Bob Dylan, and the Basement Tapes—finally released in their entirety this week, nearly five decades after they were first recorded—highlight the boorishness of both.

In one telling, Dylan is the Man Who Wasn’t There: He arrives from Minnesota with a made-up name and made up stories, takes the mantle of folk music guru from Woody Guthrie, who is lying in a New Jersey psychiatric hospital ravaged by Huntington’s Disease, and embarks on a series of magnificent lies, shifting his shape according to whatever fashions he senses blowing in the wind. Anti-war activist to electrified rock star, Jewish to Christian—no conversion was too great for this singing cynic; if you’ve lost interest in him at some point during his career, it’s because it’s true that you can’t fool all the people all of the time.

And then there are the others, those freaks who argue that Dylan was always there but you weren’t. You can usually spot them by how passionate they are about the recent albums, not the universally praised Time Out of Mind but Love and Theft and Modern Times and Together Through Life. They’ll tell you that Dylan’s sudden dip into rockabilly is some form of natural progression that you, sentimental fool still hung up on Blonde on Blonde, just don’t get because you probably never really got Dylan to begin with.

That these narratives, with minor alterations, have survived for so long is a testament to how little we understand about the voice of his generation—even after all the years and all the great biographies. The Basement Tapes offer a better story.

Dylan himself hints at it in his Chronicles Vol. 1. “I really was never any more than what I was—a folk musician who gazed into the gray mist with tear-blinded eyes and made up songs that floated in a luminous haze,” he wrote. “Now it had blown up in my face and was hanging over me. I wasn’t a preacher performing miracles. It would have driven anybody mad.”

Anybody, that is, but Dylan, who, in the eight albums he’d released prior to moving up to Woodstock and recording the Basement Tapes, was nothing less than a miracle-performing priest. But these early albums had something Dylan lost around the time of his 1966 motorcycle accident. They had faith.

To the extent that it is possible to say anything about anyone’s belief system, especially Dylan’s, it is possible to argue that passages like the one from Chronicles are proof that the bard doth protest too much. Dylan was the voice, of his generation and beyond, because his songs sounded like a dialogue with higher, hipper authorities than ourselves, funny and wrathful angels who accepted the beauty and the chaos of a perfectly wrought apocalypse like “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall,” say, as some sort of fucked-up prayer. You don’t have to dwell on Dylan’s creative process, as some pedants recently have to no good end, to realize that writing like that requires a real faith in one’s pursuit. And sometime around 1967, Dylan appears to have lost that faith.

It’s not difficult to see why. Whatever and whoever else he was, the young boy from Hibbing, Minn., whose grandfather studied the Talmud every afternoon and who attended a Jewish summer camp throughout his childhood, clearly imagined his transformation, at least in part, in theological terms. He became, in Seth Rogovoy’s helpful term, a modern-day badkhn, a joker, “a pious merrymaker, a chanting moralist, a serious bard who sermonized while he entertained … the sensitive seismograph that faithfully recorded the reactions of the common man to the counsels of despair and to the messianic panaceas.”

By 1966 that seismograph was shooting back and forth like mad. American popular music was changing, and not in a gentle, gradual way. An upheaval was in progress. Moved by the possibilities, enhanced by technology, and agitated by politics, artists were trying, in the formulation of one of the more famous of the bunch, to break on through to the other side and produce not just great albums but spiritual reawakenings. Just look at the Beatles: In 1965, with Rubber Soul, the band still sounded like a more-or-less traditional outfit. “You Won’t See Me,” for example, was a Motown-flavored bit with a bass line that would’ve fit snuggly in anything by the Four Tops or the Temptations, and “In My Life,” Paul McCartney later admitted, was inspired by Smokey Robinson, “with the minors and little harmonies” straight out of Miracles records. Nine months later, however, came Revolver. It sounded nothing like its predecessor. It had songs like “Tomorrow Never Knows,” which is a single C-chord played by George Harrison on a tambura, with drums thumping trancelike in the background and John Lennon’s voice routed from the recording console into the studio’s speaker to accommodate his request that he sound “like the Dalai Lama and thousands of Tibetan monks chanting on a mountain top.”

The Beatles weren’t alone. Everywhere, rock ’n’ roll was getting ecstatic, mystical, and impatient. Brian Wilson was tripping on acid, reading Eastern philosophy, and writing Pet Sounds. The Doors, with their long and disjointed jams, sounded more and more like a band that came together only to come apart. Janis Joplin was moving past words into primal howls, and Jimi Hendrix, as one astute observer noted, had come up with a sound that was essentially “the whole blues scale condensed into a single chord.” As 1966 turned into 1967, popular music had wild ambitions. It was, in Lennon’s memorable phrase, more popular than Jesus, and more promising, too: It promised a more pleasant sort of redemption, and it promised it right now.

It never came. Within four short years, Joplin, Morrison, and Hendrix were all gone. Breaking on through to the other side, it turned out, was beyond the reach of mere mortals. Redemption was nowhere in sight, and rock tumbled into increasingly grotesque adventures, contracting into punk or expanding into heavy metal, never again to regain its prominence in the hearts and minds of young men and women who sought it out as a source of solace, comfort, and joy.

Dylan, the seismograph, recorded all that. And you can argue that Blonde on Blonde was his one last attempt at restoring the order and keeping the peace. “Inside the museums,” he sang in “Visions of Johanna,” his great masterpiece, “infinity goes up on trial / Voices echo this is what salvation must be like after a while.” But as the scene got too wild, Dylan did the only thing he could’ve done. He retreated.

What he retreated into were the Basement Tapes. As the Beatles were moving into full Sgt. Pepper gear, and others were reveling in similar technical complications, Dylan and The Band showed up in the garage in West Saugerties, N.Y., five to seven days a week for seven or eight months, writing up to 15 songs a day, with Dylan at his typewriter, intimate and relaxed. Out poured “I Shall Be Released,” “This Wheel’s on Fire,” “Quinn the Eskimo (The Mighty Quinn)” and other gems. One by one, these songs became hits for others, including The Band itself, Manfred Mann, and Peter, Paul and Mary. But Dylan felt no need to release anything himself. Like the best of existential heroes, he was making his own meaning in a world gone mad. He recorded some of the best work of his career and kept it private. Like Camus’ Sisyphus, he had chosen to take the heroic attitude to a pursuit, making profound popular music that was getting more hopeless by the moment.

It’s useless, then, to review the newly released tapes as an album. They’re not. They’re a spiritual statement, one every bit as inspiring as deciding to keep on pushing that rock up that hill. Listen to it, and maybe you, too, shall be released.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Liel Leibovitz is a senior writer for Tablet Magazine and a host of the Unorthodox podcast.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.