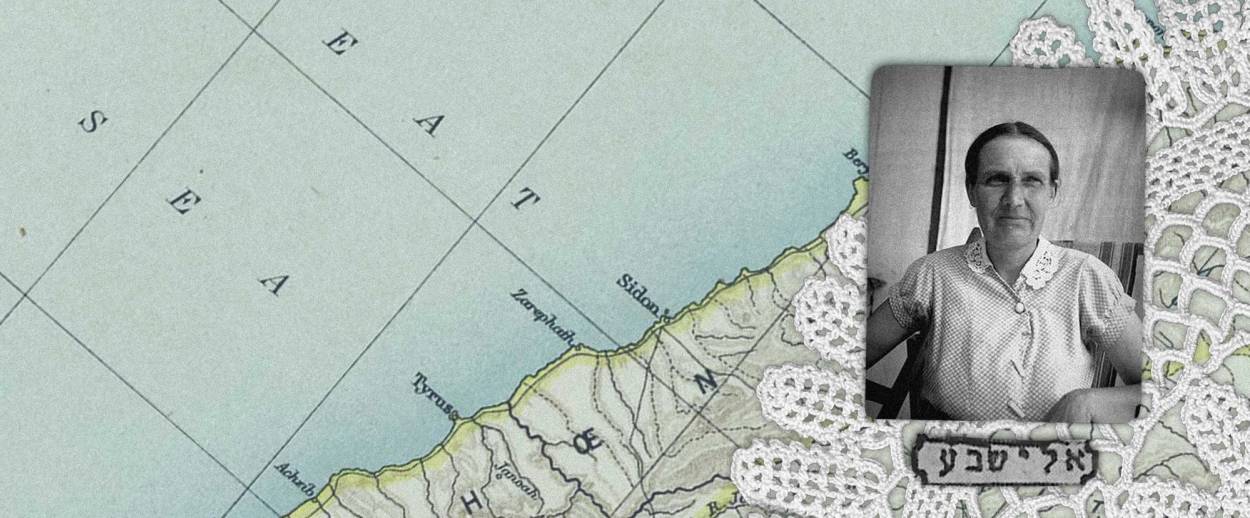

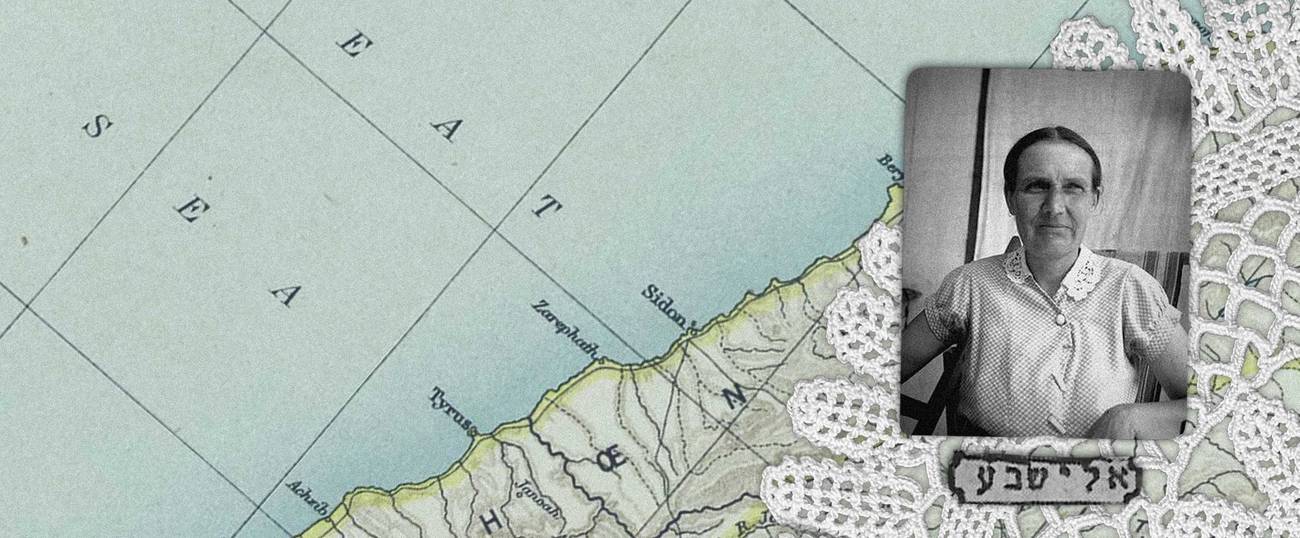

Born into a Moscow family with a complex cultural and religious heritage, including English, Irish, German, and Russian roots, Elizaveta Zhirkova became one of the great early poets of modern Hebrew and a citizen of the Yishuv, the pre-state Jewish community in Palestine. Though she identified with Jews to a great extent, Elisheva remained “a divided soul.” In a 1920 letter to a European friend she wrote, “There are two souls in me—one Russian, one Hebrew.” She experienced these “souls” not as complementary, but as competing. Moving to Palestine did not heal this internal rupture, rather—as we shall see—it exacerbated it.

Elizaveta Zhirkova was born 129 years ago today in Riazan, southeast of Moscow, in 1888. Her father was Russian and belonged to the Russian Orthodox Church. Her mother was the child of an Irish-Catholic adventurer who had settled in Russia during the Napoleonic Wars. When her mother died three years after her birth, Elizaveta was sent to live with her mother’s sister in Moscow. Of her childhood, Elizaveta wrote, “I wasn’t of Jewish descent, of course, nor was I purely Russian. My mother’s father was English (more precisely, Irish). He ran away from home as a young man and eventually settled in Russia. Then he married a German-born woman who had grown up in an English-speaking family. Therefore the next generation, my mother and her siblings, thought of themselves as English. My mother died when I was a child and I was brought up by my aunt, and it’s with her English family, rather than my father’s Russian family, that I identified.”

As a child, Elizaveta’s awareness of her complex family history fueled her imagination. The majority of her friends were ethnic Russians. Elizaveta was under tremendous pressure to conform to Russian ideas, beliefs, and traditions. Her English-German family, however, made sure to expose her to English and German as well as Russian culture. In addition, they inculcated in Elizaveta a love of the Old Testament, which she read in English. No doubt this love influenced her attraction to Jewish culture, and to Hebrew language and literature.

During high school, Elizaveta became friendly with a Jewish student. The Sabbath rituals, Jewish holidays, and kosher dietary laws that she experienced in her friend’s home enchanted Elizaveta. As she could read Hebrew and German, Elizaveta was soon able to decode the Yiddish newspapers she saw in the homes of her Jewish friends. She enrolled in advanced Hebrew classes and found a tutor to coach her. She quickly surpassed her Jewish friends both in knowledge of Hebrew and in enthusiasm for the newest trends in Hebrew prose and poetry.

During this period, news of the Irish struggles against the English, struggles that erupted in the Irish Rebellion of 1916, made a deep impression on Elizaveta. This identification with Ireland shaped her life-long sympathy not only for the Irish but also for other oppressed peoples. In a 1923 letter to a friend, she explained, “From as far back as I remember, I had a romantic attachment to small national groups, to persecuted and oppressed peoples. First, it was the Spanish, then the Poles, then the Albanians.” Concern for the sufferings of the Irish soon gave way to support of Zionism. When she met young Russian Zionists in her classes at Moscow University, their descriptions of the suffering of the Russian-Jewish masses evoked in her feelings of sympathy and identification. As Elizaveta later wrote, “Strange as it might seem, the history of the Irish is the history of the Jews. The Irish were persecuted by the English because of their Catholicism and were subject to much oppression. Just like the Jews in Russia and elsewhere, the Irish were limited to certain areas and generally discriminated against.”

Elizaveta began writing poetry in her late teens. Among the English poetry that influenced her most was Lord Byron’s Hebrew Melodies. Byron’s sympathy for the plight of the Jews, in exile from their land, stirred her. In 1919, she published two volumes of her Russian poems. In the heady post-revolutionary atmosphere of Moscow’s literary circles, however, Elizaveta’s romantic, modest poems received little attention from readers or critics. In 1920 she decided to try her hand at writing in Hebrew and her poems were enthusiastically received in the Hebrew press. They were short, lyrical and tinged with an air of melancholy. And they were not burdened with allusions to biblical and rabbinic texts, as many other Hebrew poems of the period were.

In 1920, the same year that she began to write in Hebrew, Elizaveta Zhirkova married Shimon Bikhovsky, her Hebrew tutor. She took the Hebrew given name Elisheva, the biblical original of the name Elizaveta, and adopted her husband’s last name. The marriage was a daring move for both husband and wife. Both families disapproved of the match. Elisheva’s family had expected her to marry a Russian Orthodox Christian. Bikhovsky, an ardent Zionist active in the new field of Hebrew literary publishing, was from a traditional Jewish family, and his marriage to a non-Jew caused a scandal among both his relatives and his friends. From Bikhovsky’s family, the problem was a religious one; the union was a “forbidden marriage.” For his secular friends, the problem was cultural. Traditionally, Jews and Christians did not marry, especially in Russia. Before the Russian Revolution, it was, in fact, illegal. Secular Jews considered “Jewishness” a cultural rather than a religious designation, but if that was so, a gentile could not “become Jewish.” Thus Elisheva did not convert to the Jewish religion, but to Zionism, and to the emerging Hebrew literary culture.

By marrying Bikhovsky, Elisheva was expressing her identification with Zionism and the revival of Hebrew literature. She did not convert to Judaism at this time, nor did she choose to do so later in life, when it would have been to her advantage. While Elisheva was married to Shimon Bikhovsky, his secular Jewish friends accepted her. After Bikhovsky’s death, however, she would be on her own, as she had not pursued formal religious conversion, which, in the end, proved the only path to full recognition as a Jew.

As part of her growing engagement with early-20th-century Hebrew literature, Elisheva translated, publicized, and promoted Hebrew writers to a Russian readership. She translated short stories and novels by emerging Hebrew writers like Brenner, Schoffman, and Gnessin into Russian. She also translated Yehuda Halevi’s poems of Zion into Russian. In 1921 the influential Hebrew journal Hatekufah published some of Elisheva’s Hebrew poems. Then she began to craft her own literary essays in Hebrew. Elisheva designed these essays to educate Hebrew readers both about emerging Hebrew poets and prose styles and about new developments in Russian literature. Perhaps her most influential essay, Meshorer ve-Adam, which she wrote in 1924, examined the Russian symbolist poet Alexander Blok. In the essay, she included Hebrew translations of Blok’s Russian poems. Rather than attempt to convey the “wondrous structure” of Blok’s poetry in the original, she chose to supply as literal a translation as possible. As she wrote, “In my eyes, prose translation that is precise is far better than a second- or third-rate poetic translation.”

In 1925 Elisheva and Shimon Bikhovsky, with Mira, their 1-year-old daughter, emigrated from Russia to Palestine, where a tradition of “Palestinian Jewish art” developed and prospered at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem and among artists in Tel Aviv and Jaffa. Sir Ronald Storrs, governor of Jerusalem under the British Mandate, encouraged this cultural efflorescence. In Tel Aviv, Shimon Bikhovsky established his own publishing house, Tomer Press, which published Elisheva’s work. This freed Elisheva from the ideological and stylistic constraints imposed on those Hebrew writers seeking publication in the establishment literary journals, but it also carried some risk: If Tomer Press were to fail, Elisheva would lose her access to the reading public and thus have little opportunity to get her work before the swiftly growing Hebrew readership.

The chattering classes of Jewish Palestine found the fact that a Russian-Christian poet would decide to leave Russian culture and throw in her lot with Jews nothing short of miraculous.

Shimon Bikhovsky devoted himself completely to Elisheva’s career. He served as her agent, publisher, and publicist. He organized “Elisheva soirées,” where she read her poems to Jewish audiences. He capitalized on the “exotic” nature of her appeal to the Hebrew reader. The chattering classes of Jewish Palestine found the fact that a Russian Christian poet would decide to leave Russian culture and throw in her lot with Jews nothing short of miraculous. Her first book, Kos Ketanah (A Little Cup), was the first volume of Hebrew poetry by a woman published in Palestine. Soon Elisheva was hailed, along with Rachel Bluwstein, Esther Raab, and Yocheved Bat Miriam, as one of the “four mothers” of modern Hebrew poetry.

After she published her first volume of Hebrew poetry, Elisheva turned to writing short stories about young Russian intellectuals and artists living in Moscow in the cultural ferment of the first years after the Russian Revolution. One of her signature stories, “A Small Matter,” (mikre tafel) is narrated by a young Jewish woman whose Christian friends unwittingly reveal a deep-seated anti-Semitism. At a party in a friend’s house, the narrator of “A Small Matter” overhears a conversation about a “blood libel” trial. Hearkening back to a medieval trope, a Russian court has accused Jews of using the blood of Christian children in the Passover ritual. Though most of the narrator’s friends find the accusations ridiculous, one young woman wonders aloud, “Perhaps it is true?” Through this ugly incident, the story’s protagonist gains some understanding of the social dynamics of anti-Jewish sentiment. But “A Small Matter” also operates on another level. Like many female characters in Elisheva’s fiction, the protagonist finds herself alienated from the people who surround her, whether they are Christians or Jews. In response, she turns inward, “to her own inner spiritual dream world, which she inhabits with intensity.”

While Elisheva never converted to Judaism, many of her readers were convinced that she had, and her denials seemed to have had little effect on those who wanted or needed her to be Jewish. Max Raisin, a prominent American Reform rabbi who met Elisheva on one of his visits to British Mandate Palestine, persisted in calling her a “righteous convert” to Judaism and publicizing her as “Ruth from the Banks of the Volga.” But those familiar with Elisheva’s life and literary work understood that though devoted to Zionism and the revival of Hebrew literature, she did not convert to Judaism. Jeremiah Frankel, a Zionist intellectual, dubbed her allegiance to the Zionist cause a “nationalistic conversion,” in contrast to a religiously legal, halakhic, conversion. Thus Elisheva’s resistance to formal conversion to Judaism foreshadowed later Israeli debates about Jewish and Israeli identity.

In a letter written nine years after she had arrived in Palestine, Elisheva reflected on the question of “religious identity” versus “national identity.” She made it clear that religion had played no part in her attraction to Hebrew literature, or in her decision to settle in Palestine. She wrote, “Among all of the factors that brought me to live in the land of Israel and to participate to some extent in the life of the Jews in it, there was no religious element, neither external nor internal. Essentially, I never left a different religion, nor did I join in a formal manner the Jewish religion. As I said earlier this issue is highly personal, one that remains a matter of conscience.”

Decades later, Elisheva’s daughter Mira Littel would characterize her mother’s attraction to Palestine and Judaism as a consequence of her attraction to the Hebrew language: “My mother was drawn to Judaism because of the Hebrew language. It seemed very exotic and mystical to her that a language that was almost dead for 2,000 years should come to life again through the efforts of one Eliezer ben Yehuda. For her, Judaism was like a secret society. Her brother was a linguist and thus it was natural that she went to study Hebrew at the ‘Friends of the Hebrew Language Club.’ ”

In 1929, after four years in Palestine, Elisheva further impressed her readers with the publication of a 300-page novel Simtaot (Side Streets). Here, too, she was a literary pioneer; Simtaot was the first Hebrew novel written by a woman. Elisheva had begun writing the novel in Moscow in 1925, before her departure for Palestine, and she completed it in Tel Aviv in 1929. Set among the literary and artistic bohemians of post-Revolution Moscow, the two main protagonists are Ludmilla, a Russian poet, and her lover and Hebrew teacher, Daniel. Like all of their friends, they are poor intellectuals and poets struggling to make ends meet.

On its initial publication, Simtaot was not well received. Neither the growing Hebrew readership of the day nor the influential literary critics found it appealing. In the novel, powerful forces of attraction and repulsion between Jews and gentiles are at play. These forces are both erotic and cultural. Ludmilla is deeply attracted to her Hebrew teacher Daniel. As Dana Olmert has noted, “The power and vitality of the novel stem from the description of the erotic and power relationships between men and intellectual women who are sexually liberated and independent.” In addition to the portrayal of intelligent, liberated women, Elisheva offers a complex understanding of Jewish and Christian relationships and identities. As critic Yaffah Berlovitz noted in the 1990s, “Elisheva brought new themes, and a new style, to Hebrew prose. Among these themes were: a depiction of the ‘new woman’ of the post-World War I era; the self-portrait of woman-as-creator; and the dialogue between Christians and Jews as seen from a non-Jewish perspective.”

But these affirmations of Elisheva’s literary talents came some 60 years after her death. In 1929 Simtaot was a novel ahead of its time; it would be “rediscovered” twice—once in 1977 and again in 2008. We might compare the reception of Simtaot to the reception of Henry Roth’s Call It Sleep, which was first published in 1934 and then rediscovered in 1964. From Elisheva’s correspondences with other Hebrew writers, it is clear that she intended to write at least two more novels, and one imagines that they would have reflected her experiences as an immigrant to Palestine. But a drastic change in her circumstances would force her to abandon these plans.

By 1930, Elisheva seemed on the brink of accomplishing what she had set out to do some 15 years earlier—master Hebrew poetry and prose and gain acceptance as a Hebrew writer in Palestine. Her poems were especially popular among women readers. After the horrors of WWI, readers sought a poetry that was romantic and life-affirming. They found these elements in the poems of Elisheva, and in the poems of one of the other “mothers of Hebrew poetry,” Rachel Bluwstein. In the late 1920s, many of Elisheva’s poems were set to music. “In the Grove” (Ba-hurshah) became one of the most popular Hebrew songs of the era.

But Elisheva’s popularity began to wane. Perhaps Elisheva and her husband, Shimon Bikhovsky, had overreached. They did not realize that the novelty of a “converted” writer, whether “converted” to Jewish nationalism or to the Jewish religion, could not sustain itself for more than a few years. New writers moved into the limelight, though none of them were “converts to Hebrew” like Elisheva.

In 1932 Shimon Bikhovsky died in a car accident while he and Elisheva were on a literary tour of European Jewish cultural centers. Elisheva returned to Palestine to care for her 8-year-old daughter, Mira. Elisheva was now 44 years old and had no means of support. She had never converted formally to Judaism, and this put her daughter’s status as a Jew in question. As the child of a gentile, Mira would be considered Jewish only if she pursued formal conversion to Judaism. The deterioration of Arab-Jewish relations after 1929 reinforced conservative tendencies in the Yishuv and the liberalism of the secular Jewish pioneers of the 1920s had hardened into a more conservative worldview. Shimon Bikhovsky’s close friend Yosef Haim Brenner, who spoke of a secular national identity rooted in the Hebrew language and detached from religion, was murdered in an Arab attack on a Jewish village. As the Nazi movement surged to power in Germany, the Jewish future seemed even more precarious. Many Jews reacted to the threat of anti-Semitism by “circling the wagons” both physically and metaphorically and protecting the borders of Jewish identity.

During their years in Palestine, Bikhovsky and Elisheva had not saved any money, nor had they acquired any property. After her husband’s death, Elisheva was reduced to living in a shack near the beach in Tel Aviv’s Montefiore neighborhood. Hayyim Nahman Bialik, who had achieved the status of “national poet” of the Yishuv, admired Elisheva’s talent and organized and contributed to a monthly stipend for the widowed writer and her daughter. Unfortunately, the stipend was barely enough to support Elisheva and Mira. When Rabbi Max Raisin met with Elisheva in Tel Aviv in 1935, she appeared exhausted and discouraged. As Raisin noted, “One could easily see that she was an unhappy woman, and the impression I got from our last conversation was that her unhappiness was due not merely to her material poverty, but also to the role she was forced to play as a member of the Jewish people.”

After her husband’s death, Elisheva published very few poems. Her last major poem was in memory of her benefactor, the poet Bialik, who died in 1934. The opening stanzas of “In Memory of H. N. Bialik” contrast the eternity of the sea and the stars with the ephemeral nature of all human effort. The poem closes with these lines: “I hold a book in my hands. Its pages yellow with age, it is marked with stains and with poems—the voice of a heart that has been stilled. Don’t open the book—Jealousy is bitter. But the poems will live forever!” From the publication of “In Memory of H. N. Bialik” until her death 15 years later, Elisheva would publish only a few minor poems and some book reviews in the Hebrew press.

In a mid-1930s letter to the Hebrew writer Gershom Schoffman, Elisheva spoke of her isolation and loneliness. She was disillusioned with the new society she saw emerging in Jewish Palestine and felt that there would be no place in it for writers who were not politically “useful” or engaged. As she wrote to Schoffman, “You and I, and other writers not fit for ‘real life’ should really pick up and go to London or some other place and write Hebrew literature that no one ‘needs.’ ” Though she was, of course, saddened by her husband’s early demise, her loneliness, she explained, had preceded his death. “Of course I feel very alone here … but if you want to know the truth, I felt this way before my husband died and have felt this way ever since we have moved to Palestine.”

Other Hebrew poets of the period wrote of episodic feelings of dislocation, displacement, and alienation, but in Elisheva’s case, alienation and disappointment ruled her life. During this period that she began to speak openly of her “two souls” in conflict, one Russian and one Hebrew. While other Hebrew writers, many of whom emerged from Russian culture, might have spoken of having “two souls,” they would not have described these souls as being in conflict. For Elisheva, the conflict between her Russian origins and her adopted Hebrew culture, a culture she felt had disappointed and rejected her, was overwhelmingly painful. In her essay on the Russian symbolist poet Alexander Blok, Elisheva wrote of Blok’s being torn between the idealism of his youth and the harsh realities of adulthood: “There is nothing sadder or more frightening than to witness a soul torn in two. This is what we witness in Blok’s later poems. How astute was the comment of one of Blok’s commentaries ‘that we, the readers, sit and delight in these poems—but the living soul of the poet is damned.’ ”

When WWII broke out in Europe the Jews of Palestine were both alarmed and exhilarated. Many had come to Palestine to escape from rising anti-Semitism in Europe; now the Nazis were threatening not only Europe but also the Middle East. The British had blocked the entry of Jewish refugees into Palestine, and many in the Yishuv aided “illegal” immigration whenever and wherever possible. Elisheva, living in a poor area of Tel Aviv, was worried about her future, and the future of her daughter, Mira, who was at the time in her late teens.

The outbreak of war brought new life and activity to Tel Aviv. The British army, already deployed in Palestine, greatly increased its number of troops. Jewish suppliers and merchants prospered providing for the needs of this expanded British military presence. Many Jews joined the British forces, eager to fight as Palestinian Jews under the British flag. But Elisheva saw no benefit from this prosperity. Her daughter, Mira, who had enlisted in the British army, fell in love with and married a British soldier, and then moved with him to England. Elisheva was now left completely alone, and her bitterness deepened.

Elisheva was convinced that publishers and booksellers had profited from her work while she was left in dire poverty. She had contributed to the emergence of a new Hebrew culture whose establishment now shunned her. In a 1944 letter to Mira, who was then serving in the British army, Elisheva wrote, “One day I’ll write about my 20 years in this country. The devil pushed me to devote myself to its ideals and to end up in it with all of my ‘goyishe’ naiveté. And I’ll write about all the people who exploited me and how I ended up as someone’s sacrificial lamb. Eventually, I became one of the ‘useless people’ who have no place in the ‘new’ Yishuv that is coming into being. In short, I’ve become someone that those around me define with such self-confidence as a person who doesn’t know how to help herself.”

Elisheva never gave up trying to counter the notion that she had converted to Judaism. In 1943 the Encyclopedia of Literature, a guide to the work of Hebrew writers, described Elisheva as “a convert to Judaism.” Elisheva was incensed when she read the description. She found the editor in his office and demanded the entry be corrected. This incident, once it became known, alienated the few readers who were still interested in her work.

‘You and I, and other writers not fit for “real life” should really pick up and go to London or some other place and write Hebrew literature that no one “needs.” ’

In 1945, Elisheva’s collected poems were published, but the establishment critics did not pay much attention to them. Interest in her work had faded; the poems of another of the “mothers of Hebrew poetry” Rachel Bluwstein, known to generations of Israelis simply as “Rachel,” were becoming immensely popular. In November 1947 Elisheva wrote to her American benefactor, Rabbi Max Raisin, the man who had coined the phrase, “Ruth from the Banks of Volga,” to explain her despondent frame of mind. “I am not a Jewess, and just to make believe that I am one is something I cannot do.”

But not all of Elisheva’s colleagues had abandoned her. Poets and writers of her generation paid occasional visits to her Tel Aviv shack, but as she did not encourage socializing the visits soon dropped off. She was not a bohemian; cafés and literary salons held no attraction for her. Her colleagues in the Agudat Hasofrim, the Hebrew writers’ guild, made sure that her small stipend reached her, but they could not do much about her diminishing literary reputation. As Elisheva’s daughter, Mira, remembered, “There were people who tried to help my mother, but she was a proud and hard woman, with strong principles. … She was very critical of others. It angered her that there was a lot of corruption in the country and that each person worried only about himself. It’s no wonder that folks kept their distance from her.”

Israeli statehood and the establishment of an official rabbinate influenced Elisheva’s fate. While “Jewishness” had been somewhat fluid and ill-defined under British Mandate government, the Orthodox rabbis appointed by the new Israeli government had the power to say who was and who was not a Jew. In Elisheva’s case, the question “Who is a Jew?” played out in a bizarre way at her death. In 1949 she was planning to move to England and live with her daughter, Mira. Learning of this impending move, her friends in the writers’ guild arranged for Elisheva to go to Tiberias for a brief vacation at the town’s famous hot springs. They hoped that a rest in Tiberias would help her regain her strength before her long journey. But in Tiberias Elisheva took ill, and within a week her condition had deteriorated. When she went to the hospital complaining of weakness and chronic exhaustion, the doctors found her body riddled with cancer. She died soon afterward in March 1949.

Her friends in the writers’ guild sought to bury her in the cemetery of Kibbutz Kinneret, next to the poet Rachel Bluwstein, who had been interred there in 1931. In keeping with Jewish custom, they wanted to bury her immediately—if not before the sun went down, then at least within 24 hours of her death. But the local rabbis protested that Elisheva was not Jewish, and therefore could not be buried in a Jewish cemetery. Only after the intervention of several major establishment literary figures, among them Asher Barash and Yaakov Fichman, did the Tiberias rabbis relent and allow Elisheva’s burial service to proceed.

Davar, the Yishuv’s semiofficial newspaper, did not mention this scandal in its obituary of “the poet Elisheva.” Rather, it presented the funeral as a dignified and significant event:

The funeral procession of the poet Elisheva began at the Schweitzer Hospital in Tiberias. The casket, covered with flowers, was accompanied by members of the city council, members of the workers guild, and teachers from the local schools. At 5 p.m. the casket reached the Kinneret Cemetery, where a grave had been dug next to that of the poet Rachel. At the open grave, poet Anda Finkerfeld read Elisheva’s poem “Kinneret.” Abraham Broides read a eulogy and took leave of Elisheva in the name of the Hebrew Writers Guild. The children of both Degania Kibbutzim, accompanied by their teachers, placed a wreath on the poet’s grave. Representing the agriculture settlements, L. Ben Amitai eulogized Elisheva. One of the local workers recited the kaddish.

Eleven months later, as is the Ashkenazi Jewish custom, a tombstone was placed at Elisheva’s grave. The inscription read, “Elisheva Bikhovsky, Poet.”

The emergence of the Israeli feminist movement in the 1970s and ’80s would bring Elisheva out of obscurity. Israeli feminist critics made a concerted effort to recover forgotten works written by women. In addition to the rediscovery of Elisheva’s poetry, Israeli feminists featured her novel Simtaot, the first modern Hebrew novel by a woman, as an early feminist manifesto. Literary critic Yaffah Berlovitz signaled the feminist enthusiasm for Elisheva’s work with her observation that the republication of Simtaot “reveals a creative diversity that enriched modern Hebrew poetry and prose with a feminine voice all its own—a voice that offered not only content and range but an inner rhythm with its own unique meter and cadence.”

Elisheva’s “divided soul” sprang from a cultural conflict, not a religious one. Elisheva and her husband, Shimon Bikhovsky, had adopted a secular Hebrew culture, a culture they hoped would overcome the Jewish-Christian religious difference. But their naïve expectations were not to be fulfilled. At the time of Elisheva’s death, a year after the establishment of the State of Israeli, religious difference still mattered greatly—even to those Israeli Jews who professed a secularist and universalist ideology. Over the subsequent decades of Israeli history, they would matter even more. The enthusiasm with which Elisheva and her literary works were met in the 1920s had by the late 1940s turned into ambivalence, hostility, or, worst of all, indifference. But some 30 years after her death Elisheva was rediscovered, and her work has earned the permanent place on “the Hebrew bookcase” envisioned by her mentor Hayyim Nahman Bialik.

Read Shalom Goldman’s other writings for Tablet on non-Jews in Israel here.