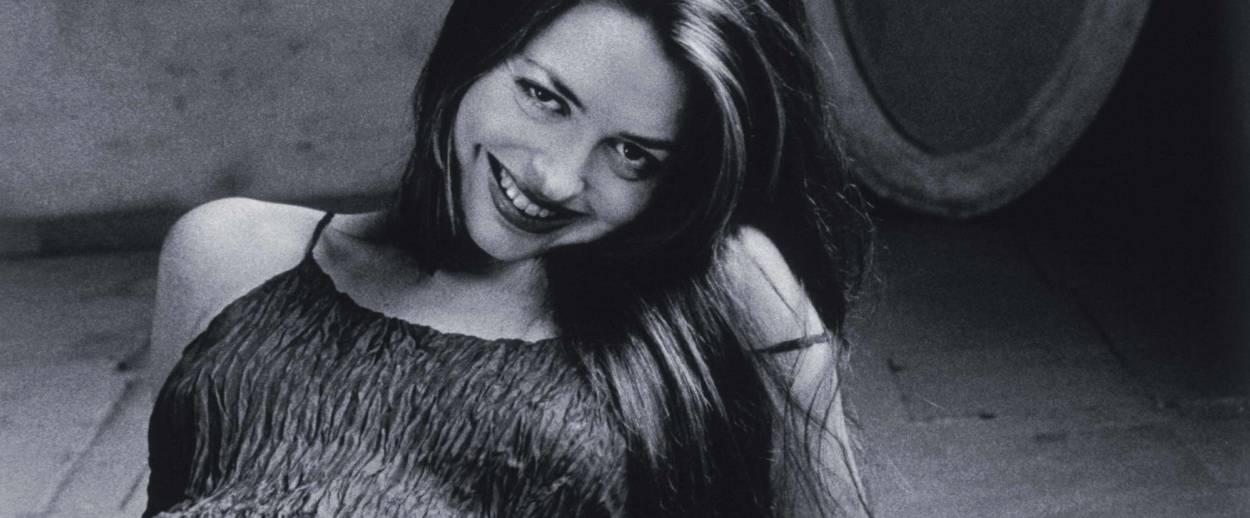

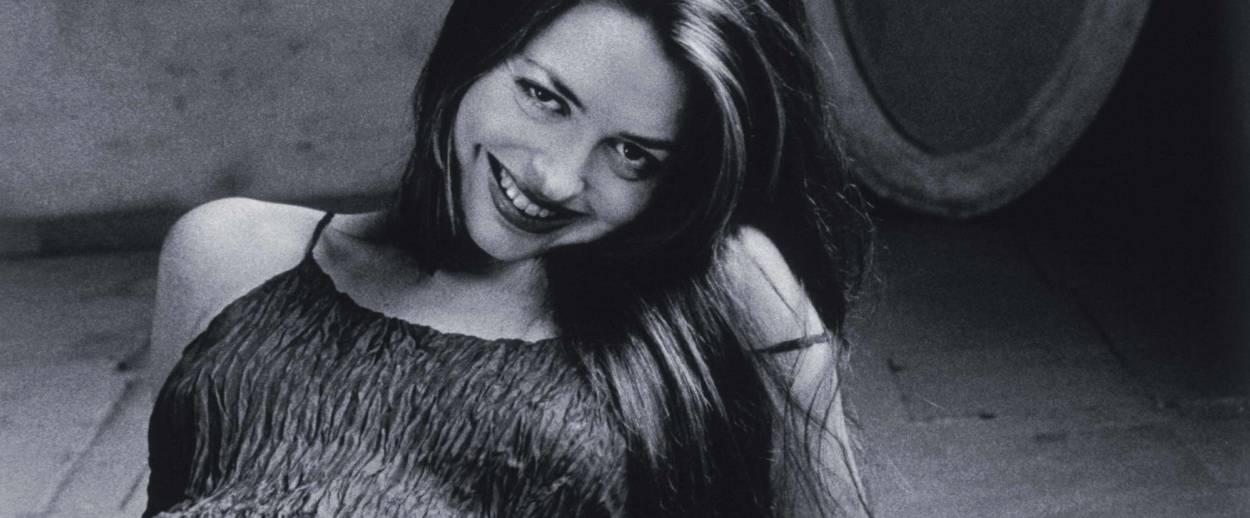

Elizabeth Wurtzel, 1967-2020

Memoirist, essayist, and friend

On Jan. 7, 2020, Elizabeth Wurtzel, inventor of the modern confessional memoir, Tablet’s pop music critic, and my close friend since high school, died from complications of metastatic breast cancer caused by the BRCA mutation. That gene was maybe the only thing she didn’t love about being Jewish. That, and Jewish Republicans.

Lizzie was maddening, annoying, an unending pain in the ass, arrogant and self-obsessed. She needed to show that she was smarter than everyone else in any room, which she nearly always was. She was an unbelievably talented writer who made millions of people feel less lonely.

In addition to sometimes being the rudest person in all of New York City, Lizzie was also oddly polite. She placed a high value on human kindness, and thought it was very important to say thank you. She valued things that she was often too busy or crazy, or forgot, to do. But the fact that she didn’t or couldn’t do simple, basic, ordinary things, like brush her hair, or clean up her room, didn’t mean she thought they weren’t important. If anything, the opposite was true.

Lizzie was often miserable, but she was never self-pitying. She took responsibility for every bad thing she ever did, and every feeling she ever felt. She couldn’t abide lying, and she saw through everyone’s scams and bad faith. At the same time, she wholeheartedly admired excellence in others, and she was immensely loyal to her friends. There was no one better to do anything fun with—see a movie with, or do drugs with, or read the newspaper on Sunday morning with, or listen to music with. She loved life, to the extent that it let her, and she always wanted more. As Jim Freed, her husband, wrote to me the other day, her highs were higher than other people’s, just like her lows were lower. She knew how precious it is to feel anything at all.

When I think about Lizzie, I always hear music. We became friends in high school when she introduced me to the Velvet Underground and the Talking Heads, and the music she loved flowed through her life. It was her lifelong answer to everything that made her feel awful. Dumb people made her feel awful. Her brain made her feel awful. But music made her feel good.

Lizzie was a rock ’n’ roll writer, by which I mean that the music she loved is everywhere in her writing. Rock ’n’ roll music shaped the way she wrote, because she listened to it all the time, and because it promised salvation. “My life got saved by rock ’n’ roll” was a promise she believed in from the time she was 14 years old, and it gave her some of the greatest pleasure and solace and relief she found anywhere. The great one-liners in her favorite rock songs were the source of her aphoristic style, which was always both achingly real and also a put-on. Out of that, she invented her own form of writing, the memoir by the unknown girl, a form that was shaped by Lizzie’s desire to be both Lou Reed and all the girls in every Velvet Underground song.

Lizzie wasn’t much for goodbyes. But since she hasn’t left me much of a choice here, I will end with lines from a song by Merle Haggard called “Sing Me Back Home,” which Lizzie loved so much. There were nights when she used to play it eight or nine times in a row, which drove me batty, even though it’s a wonderful song.

I recall last Sunday morning a choir from ‘cross the street

Came in to sing a few old gospel songs

And I heard him tell the singers “there’s a song my mama sang

Could I hear once before you move along?”

Won’t you sing me back home, with the song I used to hear

Make my old memories come alive

Take me away and turn back the years

Sing me back home before I die.

I already miss you so much, sweetie. I can’t lie. Are you coming for Passover?

***

Elizabeth Wurtzel died at age 52.

David Samuels is the editor of County Highway, a new American magazine in the form of a 19th-century newspaper. He is Tablet’s literary editor.