Zionist Women

How the art of Ephraim Moses Lilien helped redefine the figure of a newly independent, fin de siècle Jewish female

Ephraim Moses Lilien was one of the most significant Jewish artists of the modern era. With little formal academic training, Lilien matured into a master printer, a prize-winning photographer, and a renowned illustrator, publishing three major illustrated books during his brief lifetime. He befriended many of the celebrated Jewish intellectuals of the German-speaking world, including Stefan Zweig, Theodor Herzl, Martin Buber, and Chaim Weizmann. Lilien became the darling of the German Jewish art world and played an important role in the cultural Zionist art movement. He worked, albeit briefly, at the first Israeli national art school, Bezalel, in Jerusalem when it opened in 1906. Lilien’s iconic photograph of Theodor Herzl looking out over the river Rhine in Basel is better known for its emotional rhetoric than for the name of the artist who snapped the image. Israeli and Jewish history buffs recognize the photograph of Herzl, the founder of political Zionism, who stands looking east toward a hopeful future for the state of the Jews. Most are unaware that Lilien accumulated a large following for his modernist black-and-white illustrations during the first decade before World War I.

Considering Lilien’s place in Zionist visual culture, it is surprising and disappointing to scholars of gender history and visual culture that his female representations have largely been ignored. In contrast, his male images have been the focus of numerous historical, cultural, and aesthetic analyses. Scholars focused on ways to historicize Lilien’s prophetic constructions of the powerful and muscular “new male Jew” who formed a major part of early Zionist debates on nationalism, politics, emancipation, and the Jewish body.

To this day, Lilien’s prophetic construction of the muscular Jew continues to reverberate in the Israeli psyche, and appears on stamps, book covers, and Haggadot throughout the Jewish world. In 2014, more than 114 years after he first came to the attention of those early central European Zionists, the Israeli art collective Broken Fingaz created a homage to his art on the side of a three-story building in the former historic Jewish quarter in Kazimierz, Kraków, where Lilien attended art school. These images sum up the Lilien conundrum, conjuring up old, worn-out echoes of the sexually charged femme fatale, tropes that honor her role as a mere plaything for the male eye.

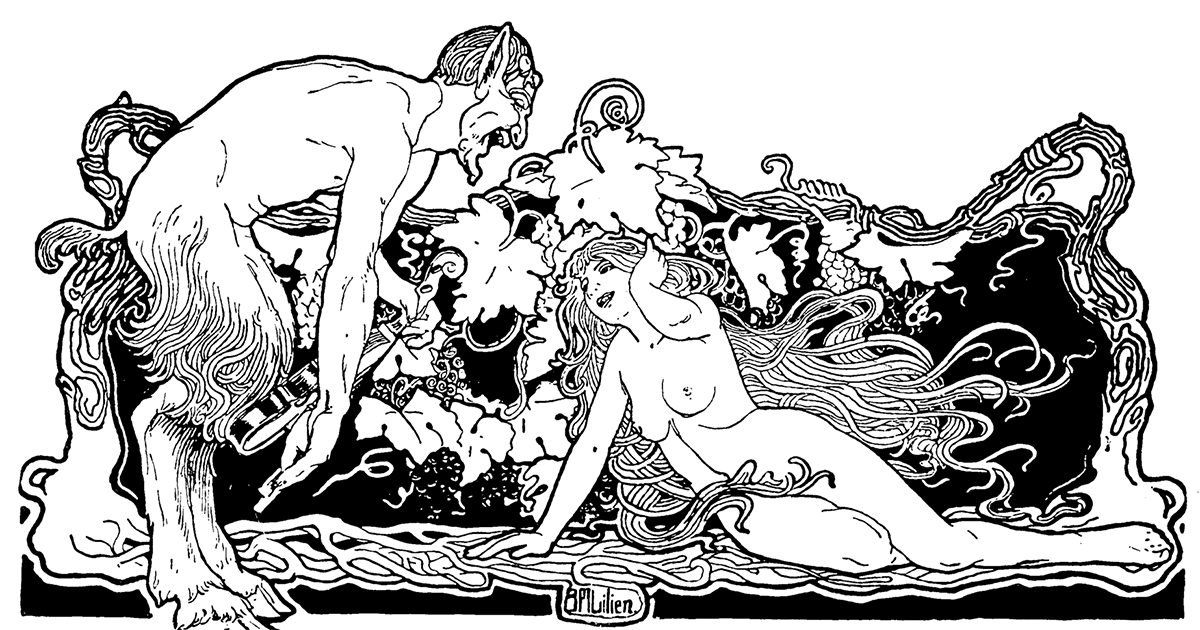

Some observers of Lillien’s early female illustrations such as My Fair Young lady, May I Dare, created in 1896, believed they were evidence of the artist’s unlimited penchant for scenes of naked young women with flowing hair about to be sexually ravished. The risqué humor makes light of his complicity with the masculine values of the period, as if teasing his male audience in an erotic, private game.

My Fair Young Lady was created for the fledgling Jugendstil magazine Jugend. Lilien created many similar femmes fatales for other journals and individually commissioned, hand-drawn bookplates. More than a decade later, in 1909, Lilien produced a vastly different image of a Jewish woman at the moment of female sexual gratification. In My Garden is my Betrothed formed part of a trilogy of drawings for what was, paradoxically, the most sensual of all the books of the Hebrew Bible, the Song of Songs. Aware of the male gaze, the woman in A Garden challenges late-19th-century sexual stereotypes that demanded subservience to her male partner. Lilien’s distinctly modern representation personified both the social and political possibilities of equality with men, a woman in charge of her own libido, and a woman on the verge of political, social, and sexual emancipation—sexually alluring, freethinking, and independent. The illustration was part of a three-volume set of images for The Books of the Bible (1909–1912).

Born in Drohobycz, at the base of the Carpathian Mountains in the Austro-Hungarian Empire of the Hapsburgs in 1874, Lilien went to art school for a year or so before moving to Munich. He arrived at an opportune moment. He worked for Jugend magazine as an illustrator and photographer in 1896, the year the magazine began. Named for the young rebels showcased in the magazine, Jugendstil became a household name. During these years Lilien created several non-Jewish femme fatales. With long flowing hair and naked bodies perfectly positioned for the stares of lecherous men, Lilien’s illustrations hardly differed from other male avant-garde artists working at the time.

Lilien moved to Berlin in 1899, just as the city supplanted Munich as the center of the German art world. He collaborated with the philosemite Börries von Münchhausen, a fascinating fin de siècle character who would later became a Nazi supporter and take his own life at the end of the war. Together, the men shared an interest in German Romantic poetry, and collaborated on a book titled Juda (circa 1900); Lilien created the illustrations and Münchhausen composed a series of Hebrew ballads. The book became an overnight sensation.

In a well-known illustration from these ballads, “The Silent Song,” Lilien fashioned a modern and Jewish artistic style, a fresh interpretation of Jugendstil for a different audience. Juda, the male hero of the story, kisses his female lover. The two bodies dissolve into an erotic embrace. Juda’s cloak, with its flat, decorative botanical patterns, swirls around them, conveying the exotic passion of their “Oriental” love. In case the audience misses the point, at bottom, next to the woman’s feet, are fecund images of fruit, ripe for the picking, while to the right two affectionate turtledoves perch on a ledge under a canopy made from the flowering bowers. What was groundbreaking for many German Jews was not just the style of the image but the subject matter.

Juda, handsome and looking a little like Herzl, kisses his female, and possibly, Jewish lover. For a German Jewish audience, the kiss was not seen as a generic Germanic kiss, but rather a specifically Jewish kiss. The emphasis on good looks and normative sexual behavior formed a major part of Zionist body aesthetics, a reaction to anti-Semitic Rassenkraft or pseudoscientific racial theories of the day that constructed different racial bodies along a teleology from white superiority to Black inferiority. The Jew’s body, as Sander Gilman argued in 1991, was racially inferior, ugly, and feminine. Gilman wrote that the Jewish face was frequently depicted as having a large prominent nose, “fleshy and overly creased lips,” curly locks of thick black hair, and “antelope eyes.”

Lilien’s use of Herzl’s face as a prototype for the construction of positive Jewish male imagery signaled the rising popularity of the political Zionist doctrine that conceived of a new race of Jewish people to counter the growing anti-Semitic projections about the Jewish body. Herzl fascinated Lilien. And it was Lilien, often supplementing his income as an artist and illustrator by taking photographs, who snapped that iconic image of his hero attending an early Zionist congress.

In contrast to the full-dress regalia of Juda, his lover is naked. Lilien drapes the bare-breasted lover in a costume of arabesque design evoking the exotic Orient. From beneath an Arab-style headdress, her long hair falls between her breasts. Adorning her upper arm is an armlet in the shape of a snake. Lilien’s female partner for the “new male Hebrew” has much in common with the provocative femme fatale of his earlier illustrations for Jugend. Acculturated German Jews such as Buber and his colleagues in the cultural Zionist movement praised Juda for its depictionof ancient Jewish male heroes. And yet Lilien’s depiction of a Jewish woman as wanton and submissive was passed over in silence.

Following his commercial success with Juda, Lilien embarked on his Bibelplan—an illustrated German Bible with Jewish and Christian editions. Constructed over four years, the work wove together Jugendstil and Orientalism into a new and innovative Jewish style that incorporated Jewish nationalism as well as modern German and Jewish culture. Although the outbreak of the First World War prevented Lilien from finishing the project, the three volumes completed (out of a projected 10) were popular throughout the German-speaking world among both Jews and non-Jews. His audience included religious Christians, secular Zionists, German and European cultural modernists, and anyone who loved richly decorated illustrations to the stories of the Bible.

The project’s success led to Lilien’s next collaboration, this time with a Protestant pastor, Ferdinand Rahlwes. An ecumenical relationship between a representative of the Christian church and a Galician-born German Jew was unusual given the precariousness for German Jews dealing at that moment with both acculturation and the specter of anti-Semitism. Jews were still excluded from important areas in German public life such as the judiciary, the military, and the state bureaucracy. Lilien and Rahlwes’ partnership was a metaphor for all that was possible within a German state that promised equal citizenship, for males at least, regardless of religion or race. And for the first time in modern Jewish and European art history, the Hebrew Bible was fully illustrated by one of its very own. Lilien used the opportunity to create heroic men and heroic women. His courageous Jewish heroines, such as Esther, Ruth, and Miriam, became positive representations of a new Jewish woman, an equal partner to his new male Jew.

Lilien’s depictions also formed part of a wider discussion about German Jewish identity and alterity at the turn of the 20th century. Lilien, like Freud, had probably grown up on a diet of Gustave Doré’s simple and dramatic images, so his Bibelplan was an act of visual redemption. The ecumenical appeal of cultural Zionism, Lilien hoped, proclaimed that Jews were more than a nation of shopkeepers, bourgeois capitalists, and intellectual, cosmopolitan effetes. Lilien’s drawings of courageous, Orientalized Jewish heroes and heroines expressed similar motives to the Jewish Wissenschaft des Judentums scholars, Abraham Geiger, Heinrich Graetz, and Ignaz Goldziher. These scholars called themselves Oriental as a badge of honor, preferring to be labeled part of the “degenerate world” of Arab and Islamic Orientalism rather than the European Christian world where they experienced frustration with alleged inferiority.

Lilien portrays a young Jewish girl on the brink of ecstasy in a work that combines sensuality with a realism not often seen in biblical illustrations.

To these Jewish Orientalists, Lilien’s images not only served as a form of visual redemption—they became a form of resistance. A way to redefine the anti-Semitic views held by German Orientalists about the inferiority of the modern Jewish body, about Judaism as an inferior religion, about the otherness of the Asiatic Jew in German society, and the perceived insignificance of Jewish art. Lilien’s women, as well as his strong, corporeal men, are depicted with dark rather than blond hair, and dark rather than Aryan eyes. Lilien’s proud, heroic women are presented in the tradition of the belle juive, defending their people in such a way as to show that their Jewishness is neither as ancient nor as outmoded as Lilien’s German secular audiences may have believed.

Lilien’s Jewish heroines remain a peculiar combination of an authentic Eastern Jewish gaze and an inherently gendered and conservative Eurocentric view of women as sexually alluring, yet maternally disposed or innately religious. Lilien sought to connect these earlier women of Zion, the matriarchs of a proud, biblical nation, with the secular politics of Zionism, and attempted to reinvigorate and regenerate an age-old religious narrative with an updated story of Romantic nationalism: a story in which the Jewish people rise up and go back east, to where they originally came from.

In his image from the Song of Songs (Songs), Lilien’s ideas reach fruition. The central story of the Songs, the sexual awakening of a young girl and her male lover, was an allegory for the love between God and the Jewish people. The two lovers meet in a landscape of fertility and abundance, a resplendent Eden, where they discover the pleasures of sex. Lilien captures the moment when the young man in A Garden declares, “the garden is my beloved, a spring shut up, a fountain sealed. Thy shoots are an orchard of pomegranates, with pleasant fruits, henna and nard … I am come into the garden, my honey … I have drunk my wine with my milk.”

The dark-eyed beauty looks as if she is about to reach a sexual climax. She clasps her own breasts, drawing attention to her nipples, while her dark hair streams in front of her like the dense and heavy overhanging pomegranate branch above her head displaying lush, ripe fruit. Clearly Jewish, she wears a striped ancient tribal costume. With minimal use of line, Lilien portrays a young Jewish girl on the brink of ecstasy in a work that combines sensuality with a realism not often seen in his biblical illustrations. The drawing was revolutionary.

Not only was Lilien the first Jewish artist to portray the sexual allegory visually, but he also portrayed the Jewish woman as an active participant in sensual and sexual pleasure. At that moment in time, no other images of Jewish women expressing sexual pleasure existed. Lilien endeavored to introduce a secular Jewish artistic language to counter the Christian imagery associated with the Songs. At that time, a complete German Jewish translation of the Songs featuring images by a Jewish artist telling the story from a Jewish perspective simply did not exist.

In view of the deeply embedded tradition of the Christian reading of the Songs in Western Europe, it is no wonder that Lilien’s original illustration seems so startling and appealing. Neither femme fatale nor biblical heroine, Lilien depicts a modern Jewish woman who defies easy categorization. He constructs a vital, original, and exotic Jewish beauty, a sensual portrayal of the contemporary Jewish woman.

Lilien sometimes merged anti-feminist Jugendstil images of the femme fatale with a Western Orientalism that worshipped an exotic, unbridled sexuality of the Eastern other. Lilien’s use of Orientalism as an artistic style to represent images of strong heroic Jewish women was not a part of those white, Western, male fantasies. Instead, his images represented a critical attempt to investigate the complexities of German and Jewish identity. To Lilien, the Orient was not simply a fanciful place, but an internal space to explore multiple or transnational identities. Lilien formed part of an increasingly large, and active group of fin de siècle Jewish writers, poets, and artists whose response to the problems of alterity was to view German Jewish Orientalism as an inspiration that helped explain their diverse identities.

Lilien searched for an “authentic” Jewish identity that would help overcome how non-Jewish Germans perceived him and his fellow Jews; not quite white and not quite German. Lilien’s sense of otherness produced tensions between his Germanness and Jewishness that demanded a psychological gestalt, an answer to the perennial question that Martin Buber’s spiritual ideas had posed to the cultural Zionists on the Jewish essence. His portrayals of Orientalized Jewish women form part of that search for identity, roots, and meaning.

Lynne M. Swarts, a historian, academic, curator, and educator, is the author of Gender, Orientalism and the Jewish Nation: Women in the Work of Ephraim Moses Lilien at the German Fin de Siècle.