Errol Morris Talked to Rumsfeld for 33 Hours. All He Got Was ‘The Unknown Known.’

The new documentary fails to elicit answers to the most important, and still unresolved, questions about the Iraq War

Errol Morris tweets. When he’s not creating Oscar-winning documentaries, writing long-form essays and books, two of which are coming out in paperback later this year, making over a thousand often fabulous commercials for Apple, Taco Bell, Exxon, Acura, Citibank, Southern Comfort, and dozens of other companies listed on his website, he has found time to post 3,220 tweets in just over 15 months. Morris has 46,500 followers—not exactly Lindsay Lohan’s 8 million, but a respectable cult following. Lohan claims to follow 319 people. Morris follows no one.

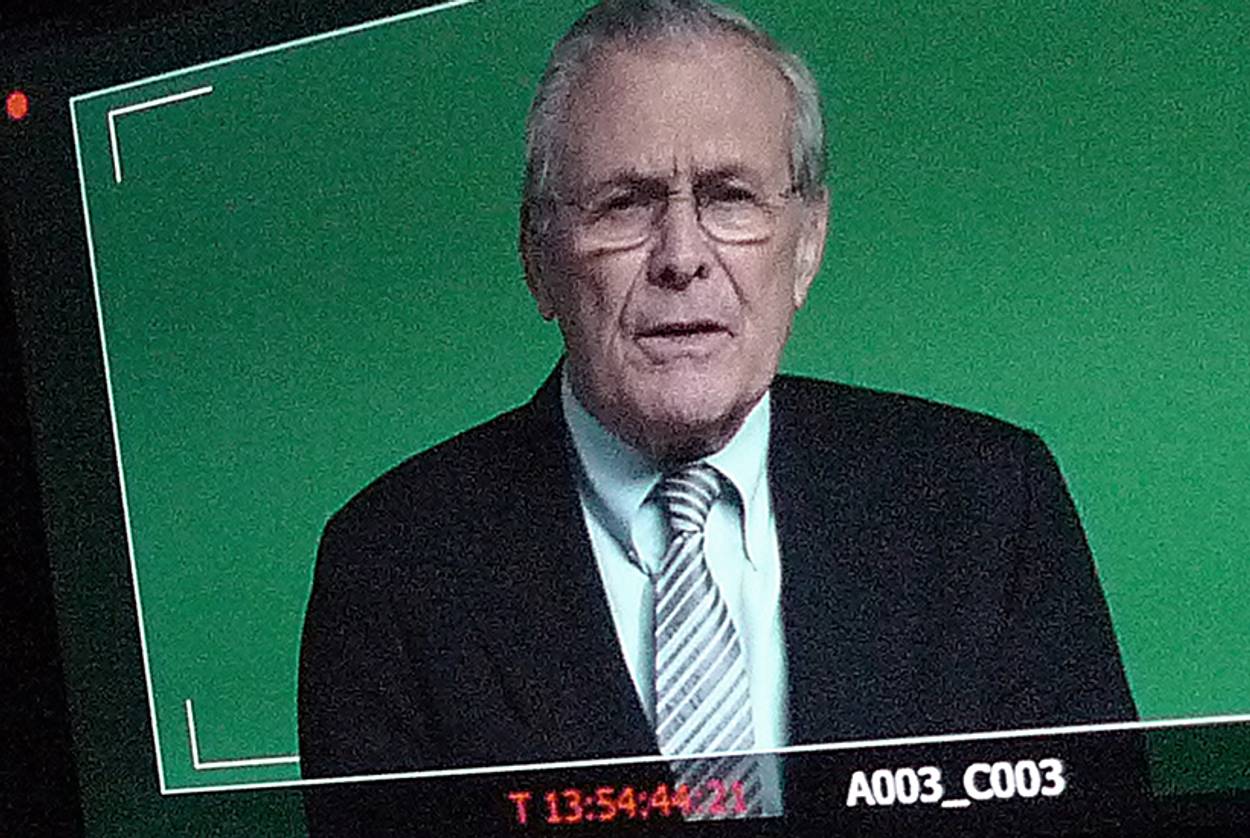

Most of Morris’ recent tweets, and retweets, concern his new documentary, The Unknown Known, or TUK, as he refers to it, his second film about a controversial secretary of defense during a disastrous war; in this case, it’s Donald H. Rumsfeld. The film is a bookend, of sorts, to his Academy Award-winning The Fog of War, about Robert S. McNamara, who presided over the Vietnam debacle under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. It is both inevitable and appropriate, Morris tells me, that the films will be compared.

McNamara and Rumsfeld have much in common. Both were identified early on as hard-charging whiz kids whose rise to power reflected talent, discipline, and raw ambition. But Morris clearly likes McNamara, as his interviews reflect. McNamara discusses the intelligence failures that result in bad policies, human fallibility, and the irrationality of war. “We lucked out” in the Cuban missile crisis when Khrushchev backed down in the near-catastrophic confrontation. Morris doesn’t push back when McNamara asserts that “in a sense” America “won” that round because “we got the missiles out without war.” He permits McNamara to utter platitudes about the human race’s need to think “more about killing,” and more “about conflict” in a WMD world.

McNamara never really accepts responsibility for his part in the war in which over 58,000 Americans and well over 2 million Vietnamese died. When there were only 16,000 American military advisers in Vietnam, he says, “I had recommended removing them all.” “We were wrong,” he notes dryly, about the false report that U.S. Navy ships had repeatedly been fired upon in the Gulf of Tonkin, which prompted Congress to authorize overwhelmingly the use of force in Vietnam. Asked by Morris about the use of Agent Orange and other chemical agents that inflicted such devastating suffering on Vietnamese and even on American soldiers exposed to the defoliant, McNamara opines: “In order to do good, you may have to do evil.” Or as Rumsfeld might have said years later, “Stuff happens.” But again, Morris does not push back.

Morris included a copy of The Fog of War when he wrote Rumsfeld a letter asking for an interview almost a decade later. He wasn’t sure whether Rumsfeld ever saw the movie, he told me—Morris, in fact, suspects he hadn’t. But later on, Rumsfeld said of McNamara: “That man has nothing to apologize for.” And so it began.

Morris traveled to Washington to meet Rumsfeld to see whether they could work with each other, as Morris put it. He offered to do several initial interviews and assured Rumsfeld that if he decided not to proceed, the public would never see them. In their first meeting, Rumsfeld invited Morris to watch him field calls from reporters. Morris, exquisitely intelligent, admitted to an interviewer about feeling awkward about the session. He described watching the former secretary’s performance with the press as almost “intimate.” Should he even be there, listening to this? Morris asks. But of course, the documentarian stays and watches.

Morris insisted, of course, on total editorial control. Giving Rumsfeld a say on final cut—which Rumsfeld may or may not have tried to demand—would undermine the project’s credibility, he tells him. But such assurances were hardly necessary. By inviting Morris to watch him fend off the press, as he had done so expertly at his memorable Pentagon press conferences, his subject had signaled his intentions: The interviews with Morris would be pure sport, verbal combat in which Morris would seek to penetrate the former secretary’s inner thoughts and motivations about the Iraq war and other mistakes, and he, Rumsfeld, would stubbornly resist the probing. From the start, Rumsfeld must have envisaged their competition as an exhibition game in which one of America’s most expert dodgers could strut his stuff.

Rumsfeld clearly enjoyed their encounters, volunteering to travel to Cambridge, Mass., to subject himself to the rigors of Errol Morris’ trademark shooting style, his “interrotron”—a word Morris’ wife coined “because it combined two important concepts” in a documentary film—“terror and interview.” But Rumsfeld clearly is not terrified. He stares unblinkingly into the camera and smiles and smiles. He cheerfully agrees to read some of his own memos—a selection by Morris of some of the 20,000 he estimates he wrote during his six years as defense secretary. Morris has done his homework; he, at least, has read the tsunami of “snowflakes” that showered down from Rumsfeld’s Pentagon office. Morris decides that the memos will enable him to tell history “from the inside out,” he says, and perhaps to evade Rumsfeld’s defense mechanisms. Rumsfeld is clearly proud of the memos. He tells Morris that he would take nothing back, even when Morris tries to show that some of the snowflakes are contradictory.

Joe Morgenstern, of the Wall Street Journal, aptly calls what emerges from their encounter—an almost-two-hour long effort to encircle and outwit a man more skilled than most at the art of deflection—the “Fog of Words.” Just as Rumsfeld adroitly evades questions he was repeatedly asked by often-exasperated Pentagon reporters before and during the war, he artfully stonewalls the Academy Award-winning filmmaker. Morris must have felt frustrated: His fascinating four-part discussion of the making of the film, in the the New York Times Opinionator section, describes his interviews with three reporters who came the closest to pinning Rumsfeld down before the war on issues he wished to avoid—specifically, the thinness of the intelligence community’s evidence that Saddam had retained chemical and biological weapons and was still trying to develop a nuclear bomb, and the lack of evidence for an ostensible operational tie between Iraq and al-Qaida, as Rumsfeld and other senior Bush officials had claimed.

In the film, Morris dutifully tries asking crucial questions about why the intelligence was so bad and why Rumsfeld, among others, believed it. But Morris seems resigned to the fact that his quarry will evade the trap. Asked about the quality of the intelligence, Rumsfeld replies calmly: “It was thought to be the best intelligence available.” Asked the “gotcha” question about whether it would have been better not to have invaded Iraq given the lack of WMD and operational ties to al-Qaida—giving him an opportunity to make both news and make Morris’ prodigious effort required viewing, Rumsfeld replies: “Only time will tell.”

Once or twice, Morris directly challenges Rumsfeld. When Rumsfeld says he never read the so-called “torture memos” about enhanced interrogation techniques, Morris interrupts Rumsfeld’s narrative. “Really?” Morris declares. Asked about whether he is obsessed with Iraq, Rumsfeld demonstrates a classic evasion technique—when mounting a defense, take the offensive. “Boy, you like that word,” he replies. Don Rumsfeld then describes own view of Don Rumsfeld, which is “cool, measured,” i.e., the opposite of obsessive.

Morris does push Rumsfeld into acknowledging an inconsistency when the definition he offers of “unknown knowns” differs from how his memo has defined it. “Yeah,” Rumsfeld cooly concedes. But the memo, he quickly adds, is “backwards.”

***

Morris is shrewd enough to understand the game. At some point in the making of this documentary, he must have sensed that Rumsfeld would reveal very little. We do not see Rumsfeld in one of the legendary tantrums that led Richard Nixon, of all people, to call him “a ruthless little bastard.” In State of Denial, Bob Woodward describes Rumsfeld’s dressing down of Adm. James L. Holloway, the chief of naval operations from 1974 to 1978, in front of 40 other senior military officers and civilians over congressional testimony that Holloway had given and attempted to explain. “Shut up,” Rumsfeld tells Holloway, who shared the episode with Woodward. “I don’t want any excuses. You are through and you’ll not have time to clean out your desk if this is not taken care of.”

Nor do we see the tormented Don Rumsfeld who emerges in a memo he wrote only two weeks after Sept. 11, following a long, difficult day at the White House with which Mark Danner opens his riveting portrait in the New York Review of Books. “Interesting day—NSC mtg. with President,” Rumsfeld’s memo begins. Asking to see his SEC DEF alone, Bush instructs him to develop a plan to invade Iraq “outside the normal channels”—“creatively so we don’t have to take so much cover [?].” If Morris asks Rumsfeld to clarify this exchange, it must have wound up on the cutting room floor. Nor does Rumsfeld read the latter part of that same memo in which Bush, a recovering alcoholic, inquires about Rumsfeld’s son, who was then struggling with drug addiction. “I broke down and cried,” Rumsfeld writes. “I couldn’t speak—said I love him so much. He said I can’t imagine the burden you are carrying for the country and your son.” Bush stands and hugs him, and Rumsfeld succumbs. “He is a fine human being—I am so grateful he is president. I am proud to be working for him.”

Morris’ film, “brilliant and maddening,” as Danner calls it, has no such emotional moments. And without any emotional or intellectual epiphanies, the long film feels even longer. There are far too many shots of snow globes and mystifying waves in a sea. Danny Elfman wrote the melodramatic score, which is more appropriate for a horror movie than Morris’ hunt for the real Don Rumsfeld.

In the end, Morris suggests, even he may not have been satisfied with his ambitious effort. “After having spent 33 hours over the course of a year interviewing Mr. Rumsfeld,” he writes in the Times, “I fear I know less about the origins of the Iraq war than when I started.” Indeed, crucial questions remain unanswered: Why did Rumsfeld believe the intelligence assessments he relied on to justify the war when he had spent a lifetime challenging the intelligence community’s earlier shoddy products? Why did he seemingly pay so little attention to postwar planning? Why did he dismiss the importance of the looting of Iraq, which helped lay the ground for the insurgency? Did he ever speak to Bush, the president he loved so much, to challenge E. Paul Bremer’s fateful decision to disband the Iraqi army? When did he begin to have grave doubts about the war’s progress? Why did he continue to back his senior military commanders’ denial that an insurgency was taking root as American and Iraqi casualty rates were climbing? And so on …

Morris fails to get Rumsfeld to answer them. For a long while, Morris writes, “I thought he’s hiding something. And then there was a terrible thought. He’s hiding nothing. There’s nothing there to hide, simply because there’s nothing there. It’s all vanity. It’s all a kind of performance art. It’s all gobbledygook. … And yet people fell for it.” Viewers predisposed to hate Rumsfeld—and judging by the responses to Morris’ haiku tweets, there are many—may conclude, as does Morris, that his film has exposed Rumsfeld as the callous, self-satisfied, empty self-promoter they imagine him to be. But those who watched the film hoping for insight into a complex man’s character and thinking, or the origins and progress of the Iraq and Afghan wars, may consider Morris’ movie a lost opportunity—one of those “unknown knowns.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Judith Miller, Tablet Magazine’s theater critic, is the author of the memoir The Story: A Reporter’s Journey.

Judith Miller, Tablet Magazine’s theater critic, is a former New York Times Cairo bureau chief and investigative reporter. She is also the author of the memoir The Story: A Reporter’s Journey.