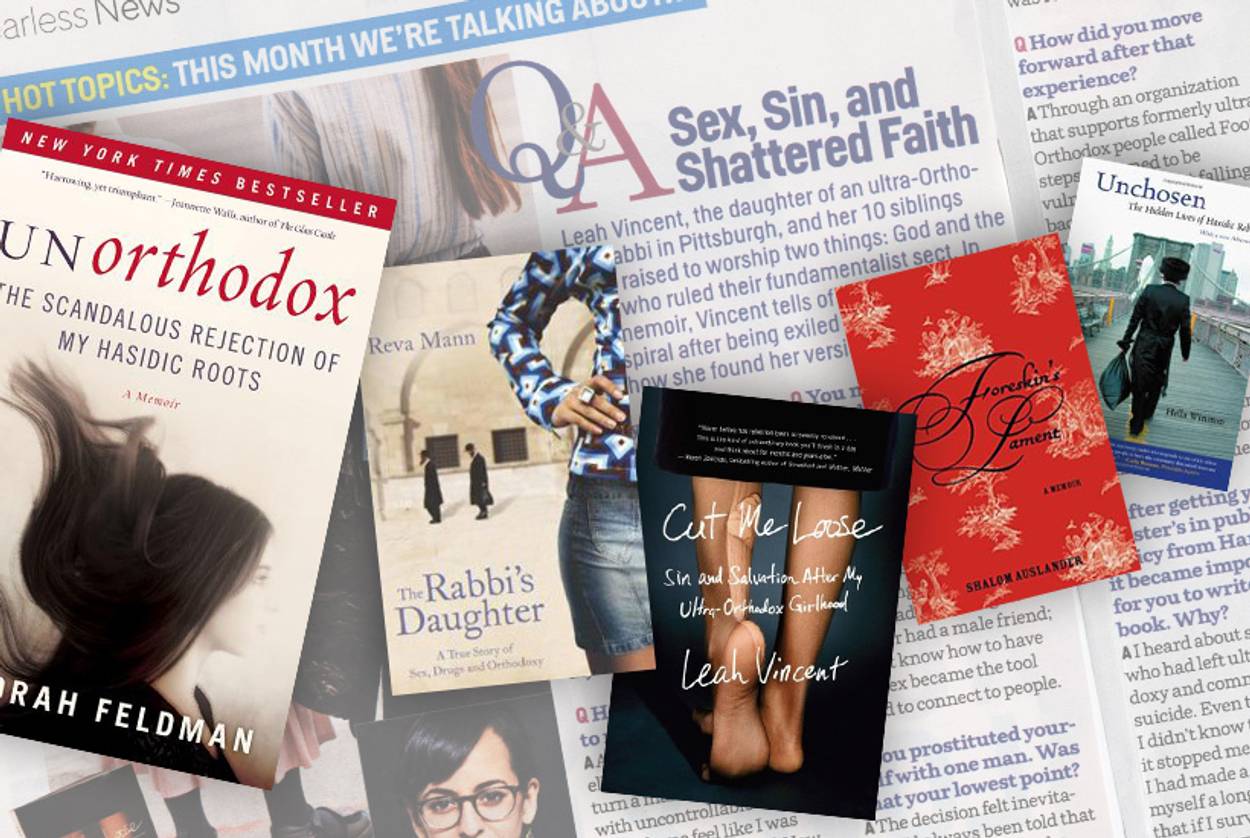

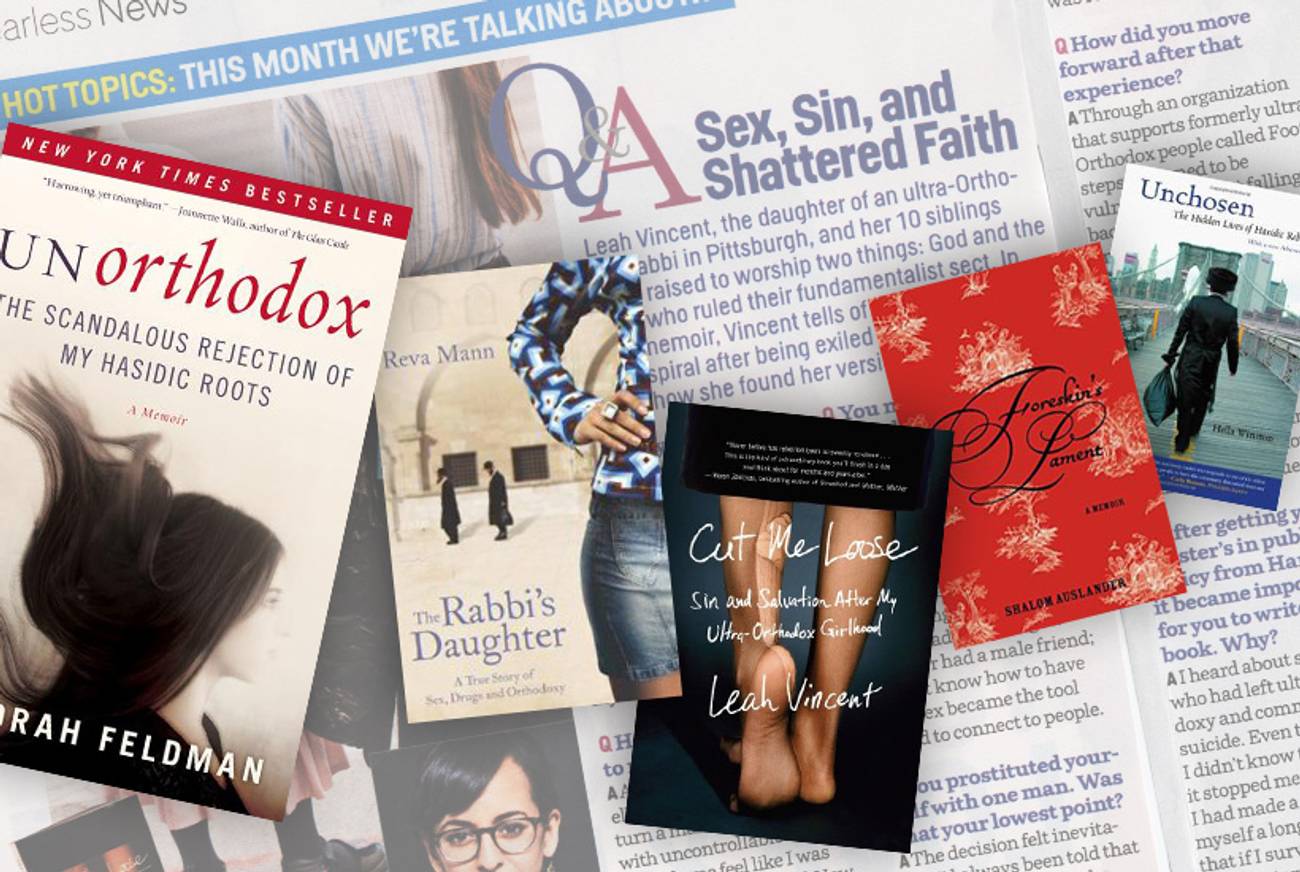

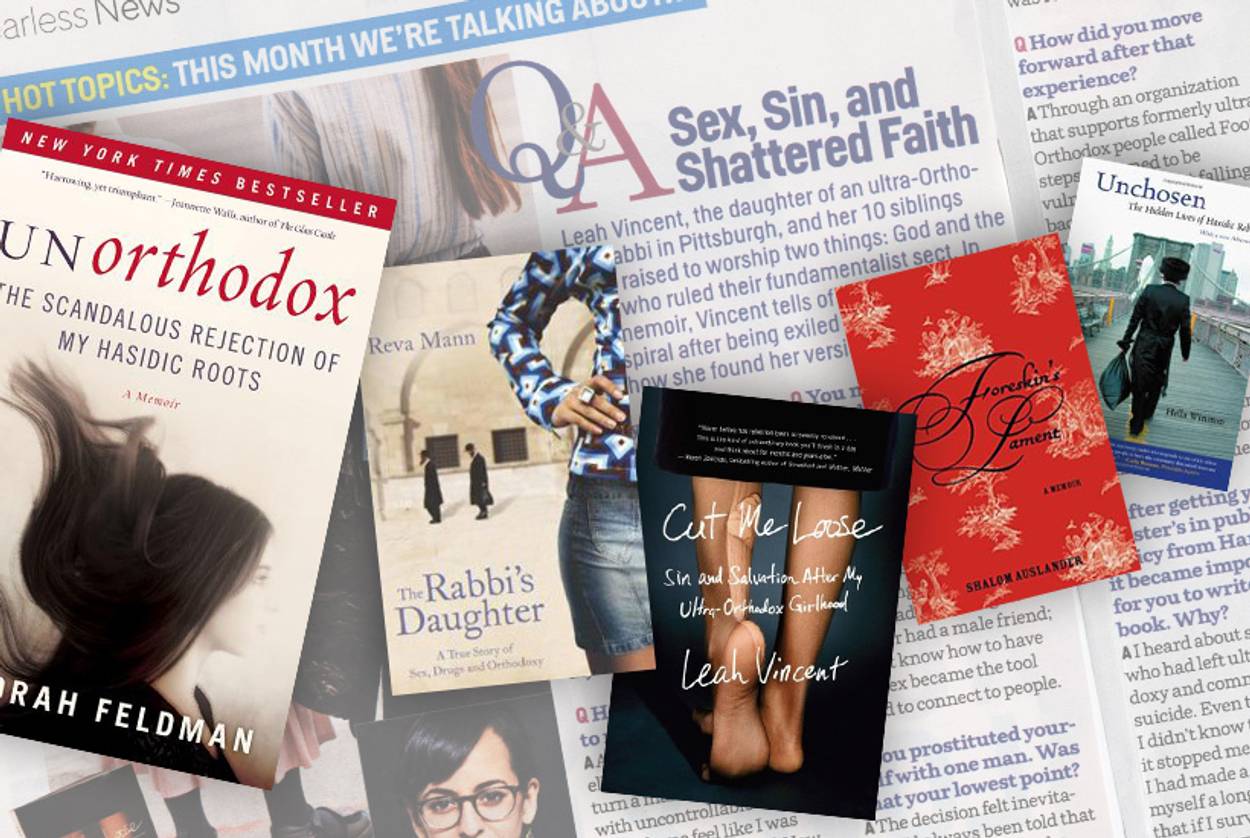

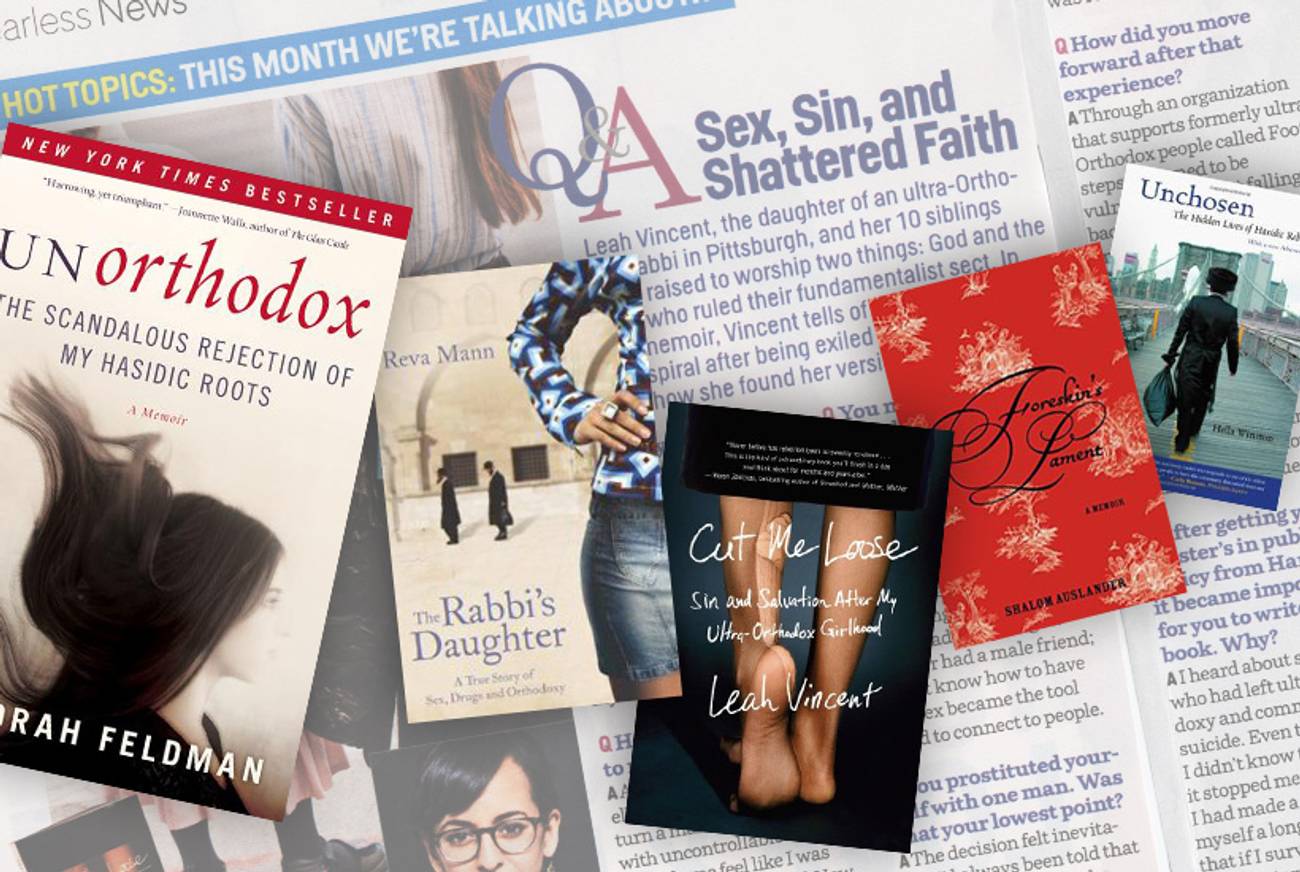

How Ex-Frum Memoirs Became New York Publishing’s Hottest New Trend

A spate of new books tells the stories of men and women who leave ultra-Orthodoxy for risky, rewarding, bewildering everyday life

Adolescent rebellion comes in many forms, but few parents would consider the desire to attend college, conversations with the opposite sex, or wearing snug long-sleeved sweaters the stuff of their nightmares. But according to 31-year-old Leah Vincent, whose parents come from a prominent rabbinic lineage, these transgressions earned her an abrupt dismissal from her family and community that left her completely ill-equipped to navigate the secular world.

Vincent detailed the seven years of displacement that followed in her new memoir (out later this month), Cut Me Loose: Sin and Salvation After My Ultra-Orthodox Girlhood, which chronicles her unhappy childhood and eventual downward spiral into unchecked promiscuity and self-cutting. During this period, Vincent was also raped by a man she had known and trusted.

“I was a very naive teenager from a very protected society, and I needed parents, desperately,” she said. “In my book, it was very important to me to be as frank about my own flaws and poor choices as I was about anybody else’s.”

Cut Me Loose has enjoyed advance buzz from writers of recently successful memoirs, like Wendy Lawless and Christa Parravani; mentions in Cosmopolitan and Vanity Fair; and brisk pre-order sales on Amazon and other online booksellers. It is also likely to renew intense public interest in the stories of men and women who leave ultra-Orthodoxy for the risky, often bewildering, sometimes dangerous, but also rewarding pursuit of what most ofAmerica calls everyday life.

***

The emerging genre of the ex-frum memoir arguably got its start in 2002, when Hella Winston, a doctoral student deeply interested in the sociology of religion, embarked on her dissertation that planned to study the spiritual lives of Hasidic women. “One of my professors who had studied the Haredi community told me that most of the researchers of ultra-Orthodoxy were men, and this inhibited them from doing in-depth research on the women in those communities,” explained Winston, in a recent interview. As she began to interview these women, however, people furtively contacted her afterward to express their dissatisfaction with their community and their desire to leave. “They saw me as a safe person outside their world who they could speak to honestly about the issues they were having,” said Winston, who quickly changed tack and went on to interview nearly 100 Satmar Hasidim from Brooklyn in various stages of rebellion against their community.

Winston mentioned several anecdotes from her research to a friend, Rob McQuilkin, whose work as a literary agent had taught him to immediately recognize the book-worthy appeal in her material. Unchosen: The Hidden Lives of Hasidic Rebels was published in 2005 and instantly earned rave reviews. Though preceded by several novels touching on themes of Hasidic dissatisfaction, like Pearl Abraham’s The Romance Reader and books by Israeli author Naomi Ragen, none of those were nonfiction accounts that so deeply delved into the struggles of people desperate to fashion new lives but equipped with few tools to do so.

And then the “rebels” began to write their own stories. Shalom Auslander’s caustic and critically acclaimed 2007 memoir, Foreskin’s Lament, discussed his crippling fear of God’s wrath despite rejecting his Orthodox faith. In 2008 came The Rabbi’s Daughter, by Reva Mann, who salaciously described losing her virginity in her father’s shul and a subsequent lesbian affair.

When Deborah Feldman’s Unorthodox: The Scandalous Rejection of my Hasidic Roots in 2011 debuted at the No. 5 spot on the New York Times Best Sellers list, it was clear that a new genre had arrived. Feldman’s story was breathlessly covered by tabloids and talk shows fascinated by her intimate descriptions—mostly negative—of the Satmar community. Other examples quickly followed, like Anouk Markovitz’s I Am Forbidden, and Hush, by Judy Brown, both fictionalized accounts of the authors’ real-life experiences with ultra-Orthodoxy, but neither came close to achieving the sales that Feldman enjoyed.

Cut Me Loose appears poised to bring the genre back to the best-seller lists. “Aside from Leah’s extraordinary story of struggling to forge an identity in a secular world, I was drawn to her manuscript because of her incredible skill as a writer,” said Ronit Feldman, Vincent’s editor at Nan Talese/Doubleday. “She writes with remarkable nuance and clarity, and her book delivers a big emotional punch.”

***

Vincent has published essays about her experiences before, most notably for Unpious, a website for ex-Hasidic writers founded in 2010 by former Skver Hasid Shulem Deen which has become a key outlet for religious and ex-religious Jews who want to give a literary voice to their experiences. Deen, 39, has his own forthcoming memoir by Graywolf Press; he is also represented by McQuilkin.

“I specifically wanted Unpious to be more curated than a blog and with a certain literary quality,” said Deen, who is also a contributor to Tablet. “It hasn’t been easy to keep up, as the ex-Hasidic world does not produce a huge number of quality writers, but I’m exceptionally proud of the pieces published on the site. They’ve impacted people in very real ways and, many tell me, changed their lives.”

Deen’s site is intended for “insiders,” readers familiar with the Orthodox world and for whom the settings and the occasional use of Hebrew and Yiddish require little translation. This, Deen believes, forces writers to exercise greater skill and create more substantive narratives.

“You can’t bullshit readers with exaggerated tales of licentious mikveh ladies or universally monstrous cheder rebbes,” Deen explained. “Insiders know the degrees to which such things are common or exceptional and can’t be bamboozled with exotics.” He reports that the site receives far fewer page views on the Sabbath and Jewish holidays, suggesting that many of the readers still strongly identify as Orthodox but find a sense of kinship in the struggles described on the site that speak to issues they might also be experiencing.

When writing for outsiders, Deen said he is cautious not to play to biases and preconceptions, mindful of the cultural voyeurism that is often at play on the part of the readers. “People are usually very interested in what goes on inside insular communities because of their fascination with what seems mysterious and different,” he said. “I don’t think there’s anything wrong with it, although I don’t always like it. To some degree, there’s a dehumanizing element involved for the writer, and I find it a little discomfiting at times to be lumped into that realm of otherness.”

For his part, Auslander has credited readers’ interest as stemming from a deeper desire to identify with these “mysterious” figures in Orthodoxy. “I’m sure that the insularity of the communities involved is a large part of the initial curiosity, but once involved in the stories, I believe there is both shock and relief at how similar these people are to everyone else,” he theorized. “Some Orthodox fathers drink too much, some daughters secretly listen to Jay-Z, and these people are just as lonely and curious and scared and human—I think that’s a comfort to people. We all take comfort in discovering that the family of man is one big family.”

Much in the same way that Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint became a defining monologue for so many Jewish American males, many of the writers interviewed for this story cited Auslander’s memoir as particular inspiration to them, both personally and professionally, as they grappled with defining their post-frum narratives.

“If that’s true, I’m delighted and incredibly gratified if the book has made even one person feel just a little bit better,” said Auslander. “That was all I wanted to do: to let someone know what it was like to believe in a Bastard Creator, a Hateful All-Knowing, to just convey the emotional, mental torture of that sort of theological OCD and its effect on one’s life. I’d read many books about God and man’s relationship to Him/Her/It, but I’d never read one that accurately portrayed the terror that I felt about God, the fear I was intentionally raised to have.”

He continued, “That the God of strict religious belief is implacable should only make it that much easier to tell him to fuck off. He’s gonna be pissed off no matter what you do.”

***

Yet because the memoir’s subjective nature and its largely introspective recollections of past events and memories is clearly vulnerable to embellishment, either for literary effect or from the haziness of time, the veracity and the integrity of memoirists is often called into question—an effect that is only magnified when memoirists are perceived as attacking the tight-knit communities in which they grew up. After reporting by the blog FailedMessiah.com—which covers crime and controversy in the ultra-Orthodox and Orthodox communities—as well as Winston in The Jewish Week, a firestorm of controversy erupted around Feldman’s book from rankled family and other members of the Hasidic community, who accused her of falsifying facts and events. A blog called “Deborah Feldman Exposed” went to tenacious lengths to discredit Feldman, pointing to, among other things, her omissions of the existence of a younger sister and her attendance at a more liberal, non-Hasidic school before the enrolling in the strict Satmar school described in the book.

Feldman was forced to release a statement amid the backlash testifying to her memoir’s accuracy. “I have offered the reader experiences that were most important to me, all the while trying my best to protect the privacy of people I cared about,” she wrote. “I prefer to avoid further speculating on the personal lives of people who have not invited the kind of public scrutiny I am allowing for myself.”

Even before her own memoir is released, Vincent faces similar challenges to her credibility. Vincent’s father, Rabbi Yisroel Miller—with whom she no longer speaks—told me that while he does not know the content of his daughter’s memoir, any allegations others have told him in his daughter’s name are “simply false.”

“Regarding her teenage years, it is clear to me that she does not, or perhaps is not always able to, separate her imaginings from the facts,” he said. “Leah first came under the care of a psychiatrist when she was 13, and over the years she was in treatment for serious disorders and self-destructive behaviors. As painful as the situation is to our family, we hope that her gaining the media attention she has craved for so long will bring her some measure of peace. We will continue to love her, always.”

Far from being fazed by accusations that she has distorted the truth in any way, Vincent says she, along with many of her peers, has frequently been called crazy or lying for speaking about the experiences that led to leaving Orthodoxy. “I would love to see a more substantial discussion with the ultra-Orthodox community about the content of my book and similar stories,” she commented.

For Winston, the feedback she received claiming she altered or created events was mostly because, she said, people simply couldn’t believe them of religious communities that tout extreme piety.

“I had a very minor character in my book who spoke of being molested at a communal mikveh, and some readers said something like that would never happen,” recalled Winston. “Of course, so many news stories since then have reported that this was not an isolated incident, but something that is much more common than many people could believe.”

Certainly, the 24/seven rapid pace of digital news coverage has increasingly revealed the public cracks in the community’s veneer and prevented the once large-scale cover-ups of communal foibles: sex abuse, rabbinic misdeeds, and other scandals. Reporters have seized upon and often sensationalized several particularly lurid stories from the Hasidic world, like the tragic murder of 8-year-old Leiby Kletzky by another Jew in Boro Park, and the trial of Nechemya Weberman, a Satmar Hasid from Williamsburg who was found guilty of sexually abusing a young girl he was supposedly counseling.

Between news reports, websites like Deen’s Unpious, and often-anonymous blogs and chat rooms where members of Hasidic communities share their own thoughts and experiences, it is hard for the ultra-Orthodox and outsiders alike to see the frum and secular worlds as entirely separate from each other, which in turn may make it easier for readers from all walks of life to connect to the universal elements in these memoirs. Winston pointed to the enthusiasm people have for coming-of-age stories, citing the many letters and emails she unexpectedly received from gay men and women, most of whom had nothing to do with the Orthodox Jewish world, after Unchosen was published. “It makes sense, because both populations risk losing their friends and family because of their ‘coming out’ journeys and defining themselves independently of how they were raised,” she said thoughtfully. “A lot of people from all walks of life identify with that struggle.”

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Tova Ross is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, and Huffington Post, and she is also a contributing blogger to Kveller.com. She lives in New Jersey with her family. Follow her on Twitter @tovamos

Tova Cohen is a fundraising communications professional and freelance writer. She lives with her family in New Jersey.