Fall From Grace

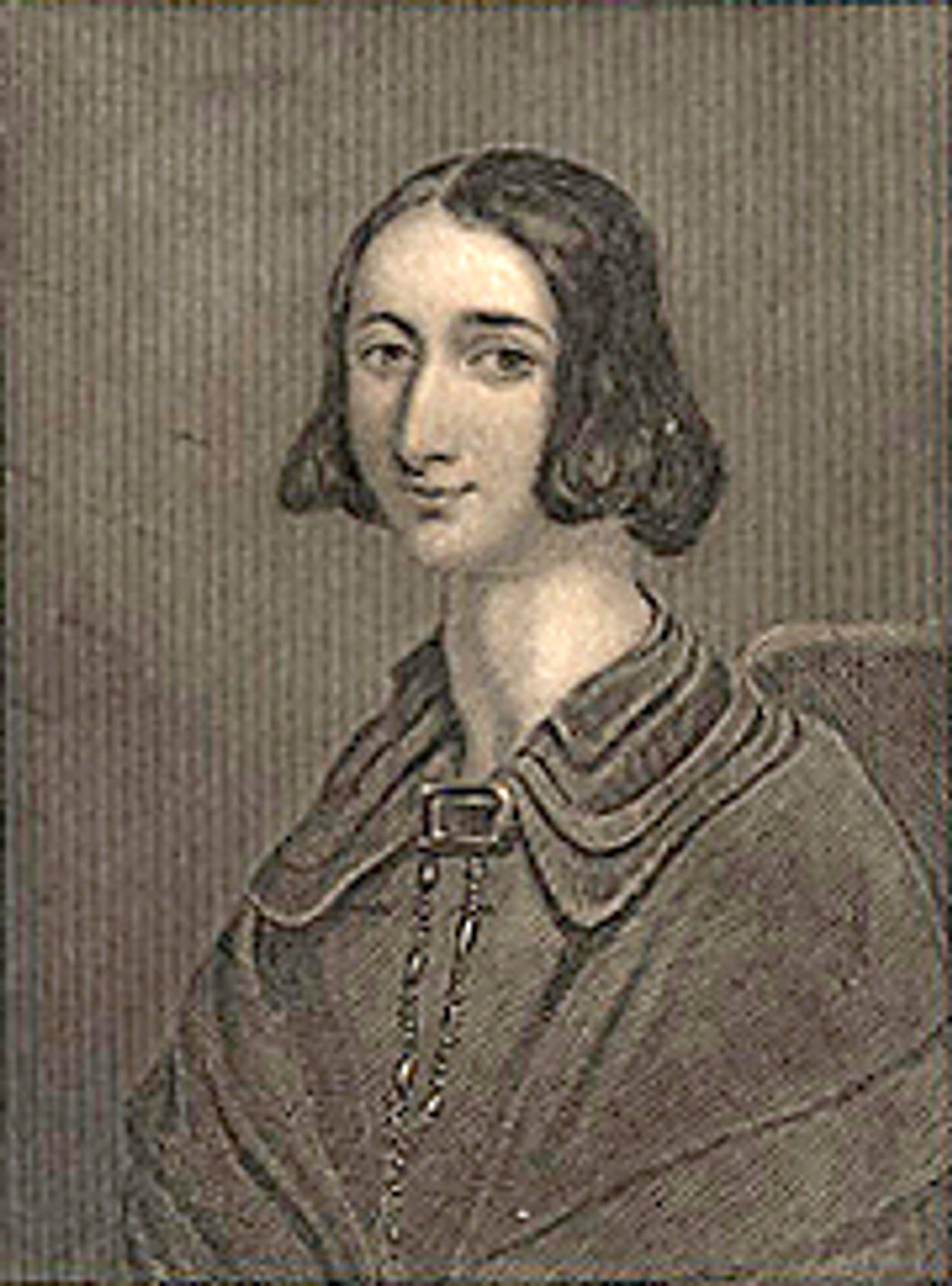

In 1843, British novelist Grace Aguilar was a household name on both sides of the Atlantic. So how come we’ve never heard of her?

Though schoolchildren today are undoubtedly acquainted with Robin Hood, the merry outlaw who steals the spotlight in Sir Walter Scott’s 1819 novel Ivanhoe, they’re unlikely to recognize the knight who lends the book its title, or Scott’s long-suffering heroine Rebecca. Beautiful, modest, and brave, Rebecca is a figure of English womanhood par excellence—novels of the period, from Camilla to Mansfield Park, were populated with similar characters—but for one “flaw”: she’s Jewish. Or, at least, she starts out that way. Shackled with a miserable, materialistic father, she falls hard for a Christian knight and trades faith for love.

Published on the heels of Scott’s tremendously popular Rob Roy, Ivanhoe sold out its entire print run in two weeks and spawned countless imitations—conversionist novels—that appropriated both Scott’s fictional milieu and his exotically Jewish heroine. Conversionism was much on the minds of 19th-century English reformists, who joined “philo-Judaic” societies, befriending Jews with hopes of converting them.

As such novels reached new heights of popularity, a 15-year-old Londoner named Grace Aguilar began work on The Vale of Cedars; or The Martyr, a novel written in direct response to Ivanhoe. Set in Spain during the Inquisition—Aguilar’s ancestors had sought asylum in England, generations earlier—the novel follows Marie, the titular martyr, as she rejects a Christian suitor named Stanley and marries a Jewish man of her father’s choosing. When her husband is murdered, Stanley is wrongly charged with the crime. To save him, Marie must admit that she is a Jew, endangering not only her own life but also a tight-knit community of crypto-Jews hiding out in a vale of cedar trees.

Confined to bed at age three with an illness that left her permanently weakened, Aguilar became something of a literary prodigy, in the style of Elizabeth Barrett Browning. At seven, she began keeping a journal. At 12, she wrote her first play. At 14, she turned to poetry. In 1834, around her 18th birthday, her tubercular father took a turn for the worse, then her mother fell ill, and the family began an economic downward spiral. Aguilar, though herself an invalid, began to think about writing as a profession, rather than a hobby. The following year, she published The Magic Wreath of Hidden Flowers, a collection of riddle poems similar to the verses read by Emma Woodhouse and Harriet Smith in Emma.). The book went through two editions, effectively keeping the wolf from the Aguilar family’s door.

That same year, Aguilar finished up The Vale of Cedars, though she didn’t seek a publisher for it, for reasons that have been lost to history. Perhaps she worried about its quality—fiction was new to her—and perhaps she worried that it was, simply, too explicitly Jewish for a mainstream audience. In the end, however, it was Judaism that would secure her first large audience.

For a woman of her day, Aguilar had a vast religious education. At thirteen, she began studying Hebrew and reading scripture under her father’s tutelage. And in the mid-1830s, she began writing on spiritual matters. At her father’s request, she translated Orobio de Castro’s Israel Defended from the French. In 1838, the text was circulated privately and fell into the hands of Isaac Leeser, publisher of the popular Philadelphia-based Jewish periodical The Occident. Four years later, Leeser published The Spirit of Judaism, a collection of Aguilar’s theological essays. Within months, Aguilar had become a household name among Jews on both sides of the Atlantic.

Multilayered and daring, The Spirit of Judaism challenged contemporary assumptions about the practice of Judaism and called for some major reforms, including an English vernacular translation of the Hebrew Bible. Most importantly, “she polemicized on behalf of both English tolerance and Jewish religious reform,” explains Michael Galchinsky in The Origin of the Modern Jewish Woman Writer, “and she offered a new vision of the spiritual needs of women in general and Jewish women in particular.”

Aguilar’s views clearly made an impact and nowhere more than in the American South, where the book made its way into the hands of the influential educator Rebecca Gratz, founder of the American Jewish Sunday School Movement (and allegedly the model for Scott’s heroine Rebecca), who began distributing it to her students. Gratz passed on a copy to her niece, Miriam Moses Cohen, who wrote Aguilar a gushing fan letter—beginning a lifelong correspondence with the author—and pushed her husband, Solomon (Georgia’s first Jewish state senator) to get involved with its promotion.

Aguilar’s sentimental style fit perfectly with prevailing Southern literary sensibilities of the time. Her poetry—published in Christian ladies’ journals—and her morally instructive novels, featuring Christian characters (in the vein of Home), brought her an enthusiastic audience of non-Jewish readers.

In 1843, as her health declined and her Christian readership grew, Aguilar was invited to write a book for Charlotte Montefiore‘s “Cheap Jewish Library” series, which the Jewish publisher, philanthropist, and writer had launched as a way to indoctrinate and elevate “the humbler class of Israelites.” Despite the runaway success of The Spirit of Judaism, Aguilar herself was still having money troubles and she quickly signed on with Montefiore. The resulting novel, The Perez Family, reads today as didactic and sentimental—to the extent that it’s barely readable—but it possesses an odd bit of historical significance: It was the first literary depiction of Anglo-Jewish life actually written by a Jew.

Concerned with issues of faith and morality, the novella is basically a chronicle of suffering: The good, noble Perezes—devout Sephardic Jews living in Liverpool—endure hardship after hardship, while maintaining a home of such grace and gentility “even poverty…looked respectable.” By 1845, the increasingly ill Aguilar was still struggling to do the same, as she tended to her dying father and finished up a collection of biographical sketches of Jewish women from the Biblical period to the modern. She wrote of her difficulties to the Cohens: “I dare not publish at a loss.”

She had nothing to fear. Critics hailed Women of Israel as a masterpiece. The next year, even as her health further declined, she published The Jewish Faith, an epistolary novel, and a long essay, “A History of the Jews in England,” in the radical Scottish journal Chambers’ Miscellany. By the end of the year, Aguilar was dead.

In the years that followed Aguilar’s mother published her daughter’s prodigious body of unpublished work: the early novels, including Vale and Home, a sequel to Home called A Mother’s Recompense, and The Days of Bruce, a Scottish historical romance and a tribute to her old nemesis—or inspiration—Sir Walter Scott. In 1853, her private theological writings, which she kept at until the very end, came out under the title Sabbath Thoughts and Sacred Communings. In death, Aguilar’s fame grew and grew, and in 1869 a retrospective edition of her collected works was published to international acclaim.

But by the end of the century, her books had fallen out of print and her name had been forgotten. The rise of feminism made her domestic ideology seem quaint, even regressive. The Anglo-Jewish community underwent a sea change as Russian and Polish immigrants fled pogroms and brought with them their own literary heroes. The values of the Victorian era—which Aguilar had embraced, if not embodied—gave way to the more radical thought of the Edwardians. Literary tastes shifted. Sentimental fiction was no longer in vogue. Grace Aguilar, a woman whose works had been advertised in the end pages of Dickens’ Bleak House, was a literary and cultural nonentity. But then again, so was Sir Walter Scott.

Justin Taylor is the author of The Gospel of Anarchy and Everything Here Is the Best Thing Ever.

Justin Taylor is the author of The Gospel of Anarchy and Everything Here Is the Best Thing Ever.