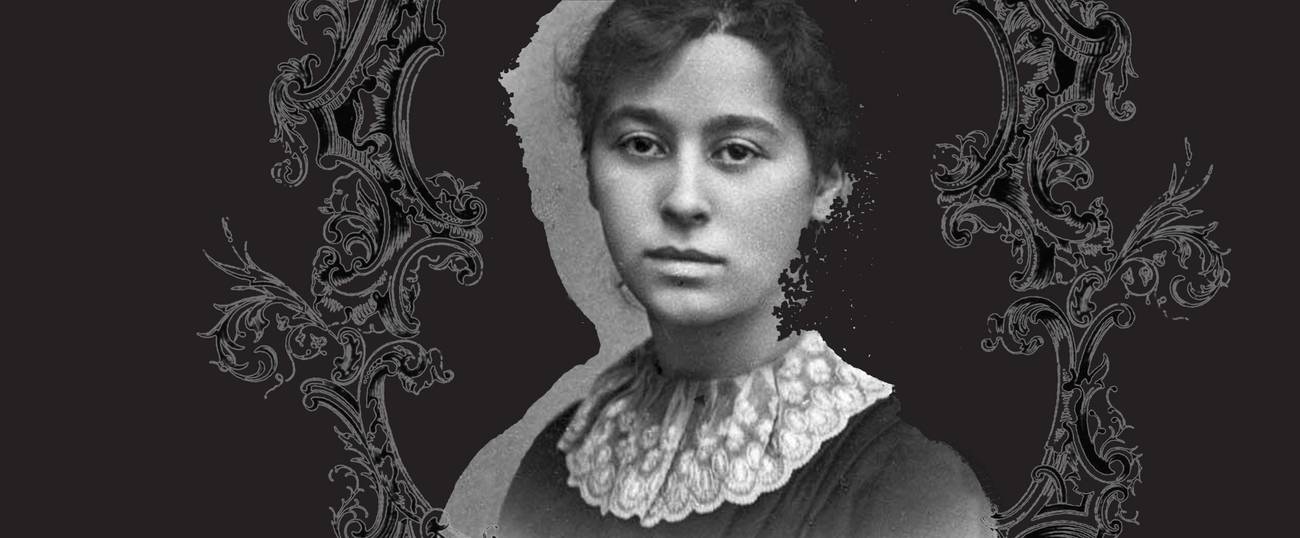

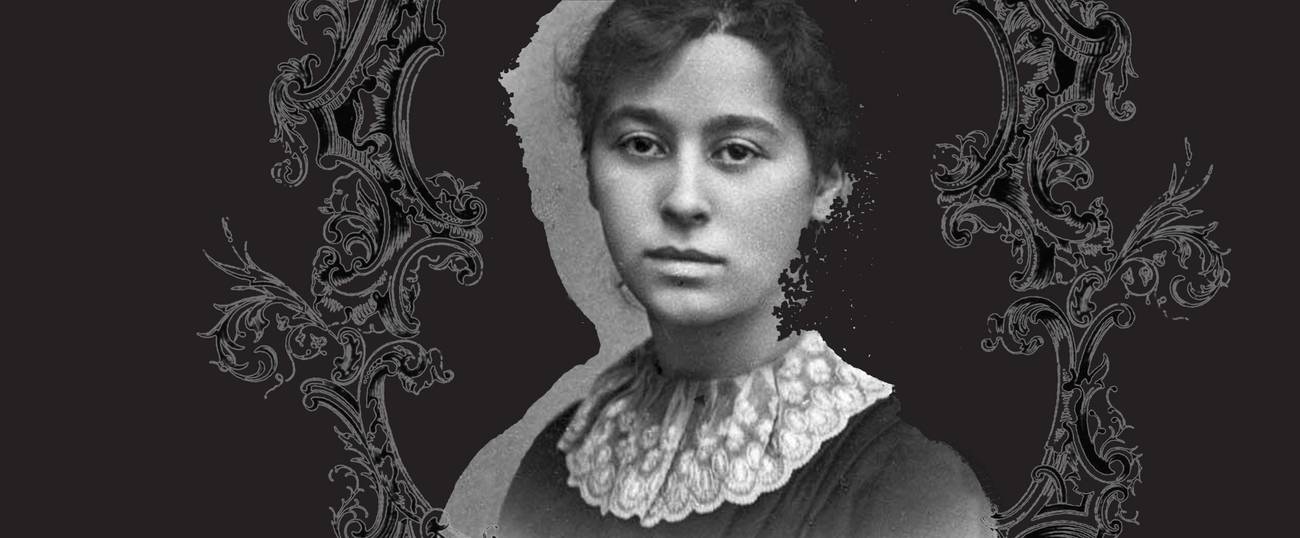

The Sad, Short, Brilliant Life of Amy Levy, Female Victorian Jewish Novelist

Uncovering the real life behind a hugely popular Israel Zangwill character, 127 years after the night she committed suicide at age 27

In Children of the Ghetto: A Study of a Peculiar People, Israel Zangwill’s 1892 novel of Jewish life in late Victorian London, an urchin who trudges through slummy East End streets in the first chapter grows up to write her own fictional ethnography of London Jewry. Esther Ansell’s Mordecai Josephs is an “opprobrious” portrait of the Jewish nouveaux riche. Published under a male pseudonym, it causes outrage in the press and is denounced by other characters as anti-Semitic treachery, the “putting of weapons into the hands of our enemies.”

Children of the Ghetto had its detractors, too. The question of whether Zangwill’s novel was good for the Jews was hotly debated on the letters page of New York weekly The American Hebrew, with businessman Cyrus Sulzberger asserting that any accusation made of anti-Semitism “will find substantiation” in the novel. (Cyrus’ cousin Mayer Sulzberger, who co-founded the Jewish Publication Society of America, was Zangwill’s U.S. publisher.) Critics’ reactions were mostly positive, however, and the public started reading in droves; in the U.K., Zangwill entered history as the author of the first Anglo-Jewish bestseller.

Posterity has been less generous, alas, to the real-life writer on whom fictional controversialist Esther Ansell was modeled: Victorian poet, essayist, and novelist Amy Levy. A Londoner from an assimilated upper-middle-class family—her parents, Isabelle and Lewis, were cousins whose forebears had arrived in England in the 18th century—Levy published her first poem at the age of 13. At 17, she became the first Jewish woman to study at Newnham College, Cambridge. During her short career, she published three volumes of poetry and three novels, and contributed journalism and short stories to periodicals including The Gentleman’s Magazine and Oscar Wilde’s Women’s World. Once hailed as a genius by Wilde, today Levy is little-known outside academic and poetry circles. Yet, in more ways than one, she was a catalyst to Zangwill’s immortality. In fact, had she not tragically committed suicide at the age of 27, we might never have heard of him at all.

***

The inspiration for Zangwill’s Children of the Ghetto came from Mrs. Humphry Ward’s 1888 publication of Robert Elsmere, a tale of an Oxford clergyman who suffers a crisis of faith in Anglican doctrines, which sold more than a million copies. Mayer Sulzberger was thus prompted to seek out an author who could, under the auspices of the JPS, write a Jewish version of Ward’s best-seller. Since Levy’s Reuben Sachs: A Sketch had appeared that same year and was also successful, albeit in a more minor fashion—it was published on both sides of the Atlantic, and the English edition from Macmillan soon went into a second printing—the Jewish Englishwoman was Sulzberger’s first choice. It was only after her untimely death in 1889 that an alternative was suggested: 26-year-old Zangwill, the future Zionist campaigner who was then an editor, satirist, and playwright with a few works of prose fiction under his belt, including a co-authored pseudonymous novel. After some negotiation, he accepted the commission, along with an advance of £200, for Children of the Ghetto.

Levy, having in effect handed the ambitious young author his big break, would continue to make her presence in his work: According to his biographer, Joseph H. Udelson, she shaped Zangwill’s literary sensibility more than any other Anglo-Jewish writer. In 1886, British newspaper The Jewish Chronicle had published Levy’s essay “The Jew in Fiction,” wherein the 24-year-old argued that no novelist had made a serious attempt “at grappling in its entirety with the complex problems of Jewish life and Jewish character. The Jew, as we know him today … has been found worthy of none but the most superficial observation.” Guilty of superficial portrayals, she charged, were Sir Walter Scott, Dickens, and Thackeray. As for George Eliot, though Daniel Deronda was celebrated as the first Zionist novel in English literature (you can still find a George Eliot street in Jerusalem, Tel-Aviv, and Haifa), Levy dismissed its Jewish characters as unrealistic and overly noble. That “little group of enthusiasts,” she acerbically termed them, “with their yearnings after the Holy Land.”

“[G]rappling in its entirety with the complex problems of Jewish life and Jewish character,” was precisely what Zangwill set out to do in Children of the Ghetto. His inclusion of Levy-proxy Esther Ansell pays tribute to Reuben Sachs, the pioneering work in this regard. Like Mordecai Josephs, Levy’s story focuses on an extended Jewish family who, living in bourgeois London splendor, overvalue success and prosperity while neglecting their spiritual and intellectual heritage. As such, they are a deliberate counterpoint to Eliot’s virtuous and idealized Jews. “I think,” says one character of a dinner guest and new convert, “that he was shocked at finding us so little like the people in Daniel Deronda.” Replies another: “Did he expect to find our boxes in the hall, ready packed and labeled Palestine?”

Yet Levy also reproduces a stereotype perpetuated by Eliot, one prevalent at the time: that Sephardic Jews were beautiful and physically robust, and Ashkenazic Jews ugly and frail. In Daniel Deronda, the handsome hero—whose Iberian ancestry is right there in his surname—has a face “rich in youthful health, and with a forcible masculine gravity in its repose.” By contrast, his tuberculosis-racked mentor, the mystic Mordecai Cohen, is yellow and gaunt. Levy’s heroine, Judith Quixano—the impoverished scion of Portuguese vieille noblesse—is “exquisite,” the reader is told, with “features like those of a face cut on gem or cameo,” her skin glowing “with a rich, yet subdued hue of perfect health.” Germanic Jew Reuben Sachs, around whose ill-fated desire for Judith the plot pivots, is not only unimpressive in appearance but debilitated in body and mind. He has a weak heart, and we first meet him in the wake of a nervous breakdown.

Reuben Sachs is peppered with fashionable Darwinian words like “survival,” “fitness,” “instincts,” and “degenerate,” the subtext being that the Ashkenazim are an overbred people in racial decline. “More than half my nervous patients are recruited from the ranks of Jews,” a doctor tells Reuben. “You pay the penalty of too high a civilization.” He echoes Levy’s gloomy observation in an earlier essay that “the Jewish child, descendant of many city-bred ancestors as he is, is apt to be a very complicated little bundle of nerves indeed.”

Levy was a depressive who suffered from various other ailments, including partial deafness. She was also preoccupied with the apparently baseless idea that she was unattractive. (Some of her unpublished work was signed U.G.L.Y.) So her worldview was no doubt colored by her own unhappiness, as well as that of her beloved younger brother Alfred, who died at age 24 of uncertain causes—his death certificate simply said “paralysis, exhaustion.” Moreover, the perspective of Reuben Sachs is complicated and shifting; in particular, it is unclear if the opinions of the semiomniscient narrator reflect those of the author, who may have intended to satirize gentile prejudices. Biographer Linda Hunt Beckman has suggested that, in her most objectionable sentences, Levy was deliberately mimicking the descriptions of Jews found in the novels of Anthony Trollope.

Nevertheless, to late-19th-century readers of Reuben Sachs, the characters veered inexplicably close to malicious caricatures. Not only had Levy placed undue emphasis on their physical flaws—at one point the narrator refers to “the ill-made sons and daughters of Shem”—she had foregrounded their fondness for conspicuous consumption. “Material advantage,” muses Judith on the values her friends had instilled in her, “things that you could see and touch and talk about; that these were the only things which really mattered, had been the unspoken gospel of her life.”

Reuben Sachs caused a dreadful scandal, with Levy accused in various quarters of vitriol and hatred of her own community. “She apparently delights in the task of persuading the general public,” wrote the reviewer for Jewish World, “that her own kith and kin are the most hideous types of vulgarity.” The Jewish Chronicle chose not to review it, despite Levy being a contributor. (Later, a review of another book referred in passing to the novel as “intentionally offensive.”) Instead, the paper ran an article titled “Critical Jews,” which, without mentioning names, bemoaned the “deleterious” effect of “Israelites” who offer “ill-natured sketches” of Jewish life.

Children of the Ghetto presents an apologia of sorts for Levy. Raphael, a journalist and stand-in for Zangwill, recognizes that Mordecai Josephs was written with good intentions and that “even the satirical descriptions were but the revolt of Esther’s soul against mean and evil things.” Eventually, Raphael proposes marriage to Esther and, on the final page, their first kiss is “diviner than it is given most mortals to know.” It is a conventional happy ending denied to Levy herself, and also to her character Judith: In Reuben Sachs, would-be sweethearts Reuben and Judith are pressured to marry other people for money, not love, and the emotional ruin wrought by that custom—commonplace enough in Victorian society but, suggests Levy, even more deeply ingrained in “the community”—stands out as the sincerest message of the novel. Marrying for love would be taken up again by Zangwill in The Melting Pot, his famous 1908 play (and popularizer of America’s favorite metaphor for itself) in which the hero, surely not coincidentally, shares Judith’s family name, Quixano.

***

When she decided to take her own life, Levy was nearly 28. Deeply romantic, and possibly gay—there was an ardent attachment to glamorous garçonne writer Vernon Lee—Levy would have found a loveless arranged marriage an intolerable prospect. But despite her success as a writer and her relative freedom, the path ahead must have seemed like a difficult one for a brilliant, painfully neurotic, heavily-censured single Jewess. Perhaps worst of all, she feared that the joy she longed for was chimerical, as she expresses in this poem from her posthumously published final collection, A London Plane-Tree, and Other Verse:

O is it love, or is it Fame

This thing for which I sigh?

Or has it then no earthly name

For men to call it by?

I know not what can ease my pains,

Nor what it is I wish;

The passion at my heart-strings strains

Like a tiger on a leash.

On the night of Monday, Sept. 9, 1889, Levy shut herself in a room at her parents’ house in Bloomsbury, blocked any sources of ventilation, and went to bed with a charcoal fire burning, knowing that the carbon monoxide would be fatal. As per the instructions in her will, she was the first Jewish woman in Britain to be cremated.

In Levy’s last story to be published, Cohen of Trinity, a lauded but disillusioned young writer named Alfred Lazarus Cohen kills himself, and “[t]he small section of the public which interests itself in books discussed the matter for three days.” Though Levy’s own demise was discussed for somewhat longer, over the ensuing decades her name sank into obscurity. The faint memory of her short life was even overlaid with Zangwill’s fictionalizing of it: A 1912 article about “forgotten poetesses” characterized the privately educated stockbroker’s daughter as an urban waif whose sensitive soul had somehow transcended her grim, deprived environment—a more accurate panegyric to Esther Ansell than to Levy.

Thankfully, the 21st century has seen some recuperation of Levy’s real life and achievements, including new editions of her novels, two biographies, and, this year, the inauguration of a commemorative literary prize in her name. For a guide to how Levy herself wished to be remembered, we might look to the concluding lines of Cohen of Trinity. Pondering Cohen’s shocking suicide and its possible motive, the narrator wonders if “amid the warring elements of that discordant nature, the battling forces of that ill-starred, ill-compounded entity, there lurked, clear-eyed and ever-watchful, a baffled idealist?”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Emma Garman has written about books and culture for Newsweek, The Daily Beast, Salon, Paris Review Daily, Words Without Borders, Longreads, and many other publications. Her Twitter feed is @emmagarman.