The Labyrinth

Tablet Original Fiction: God never had a reason to leave—not for meat, not for bread, not even for incense

Here is Judaism on one foot: All who see God die; therefore, God must always be hidden.

Early on, this was simple to accomplish. God was provided with a house and meals were delivered to His doorstep, every day, morning and evening, so that He would never have a reason to leave—not for meat, not for bread, not even for incense.

This worked well until the Temple was destroyed. At the precise moment that the sanctuary walls were breached, a massive bright presence shot out from the crumbling stonework and into the streets, killing at will throughout the city, until the rabbis came and trapped Him in the study hall, where God was restricted to a space no larger than four square cubits. God resided in that space for several years, murdering all those brazen enough to barge in or unfortunate enough to open the door by accident or even be in the vicinity when God, now starved of sacrifices, emerged from His new dwelling to find a quick kill, a pleasing smell. Many people died, but this was at first ignored. It was not until a thousand bodies had piled up in the streets that the rabbis decided the problem required a solution.

At a convening in Yavneh, the rabbis plotted. God could be transferred to another house, but it would do no good: Since no resources were available to supply His cravings with sufficient regularity, the killings would continue, only to explode should the new house be destroyed like the Temple before it. Yes, said the rabbis, the Lord must live in a house—but it must be a safe house, impervious to decay, so that there would be no chance of escape. The house also needed to allow God and humans to communicate, and—on rare occasions—to conduct sacrifice.

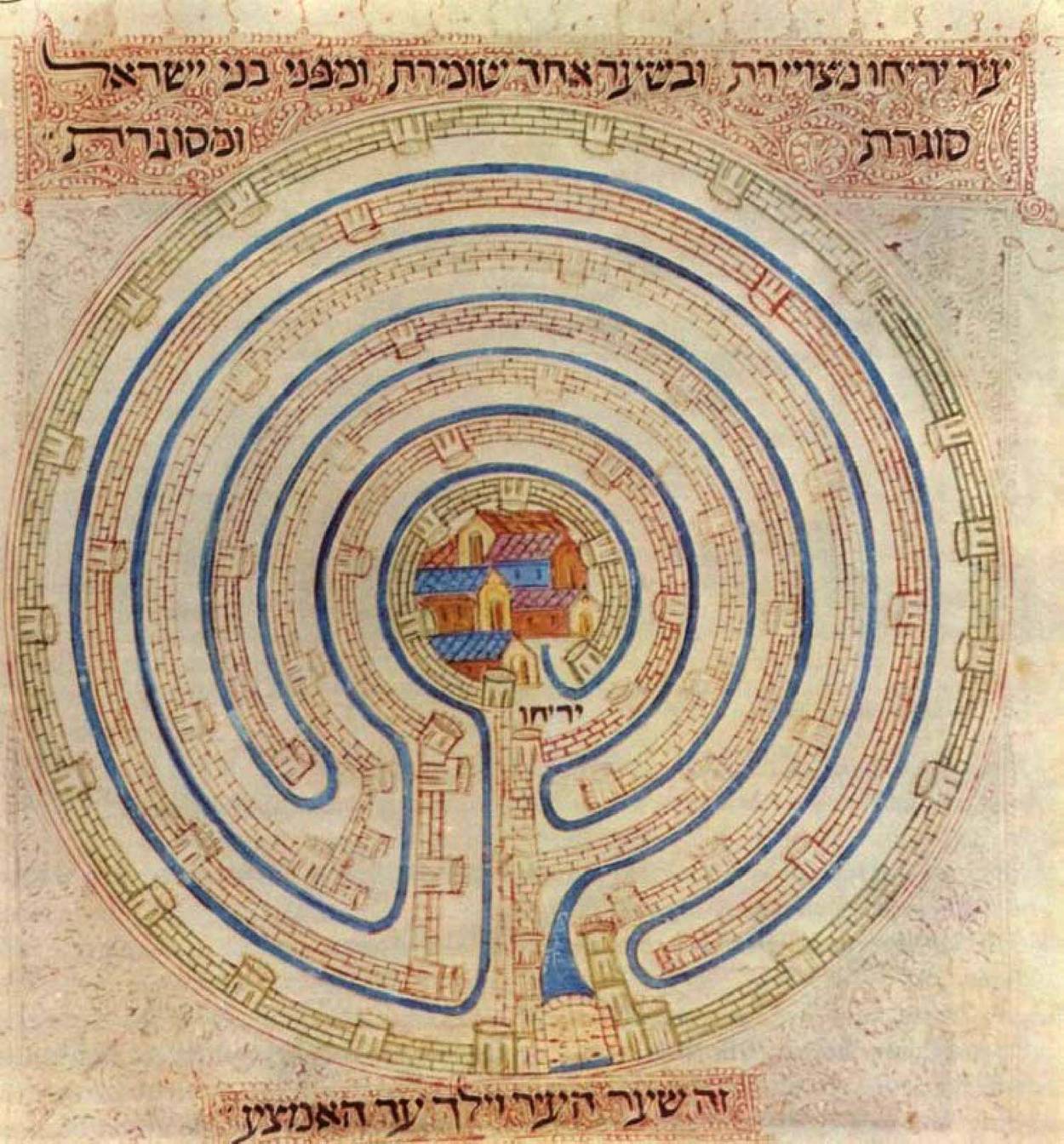

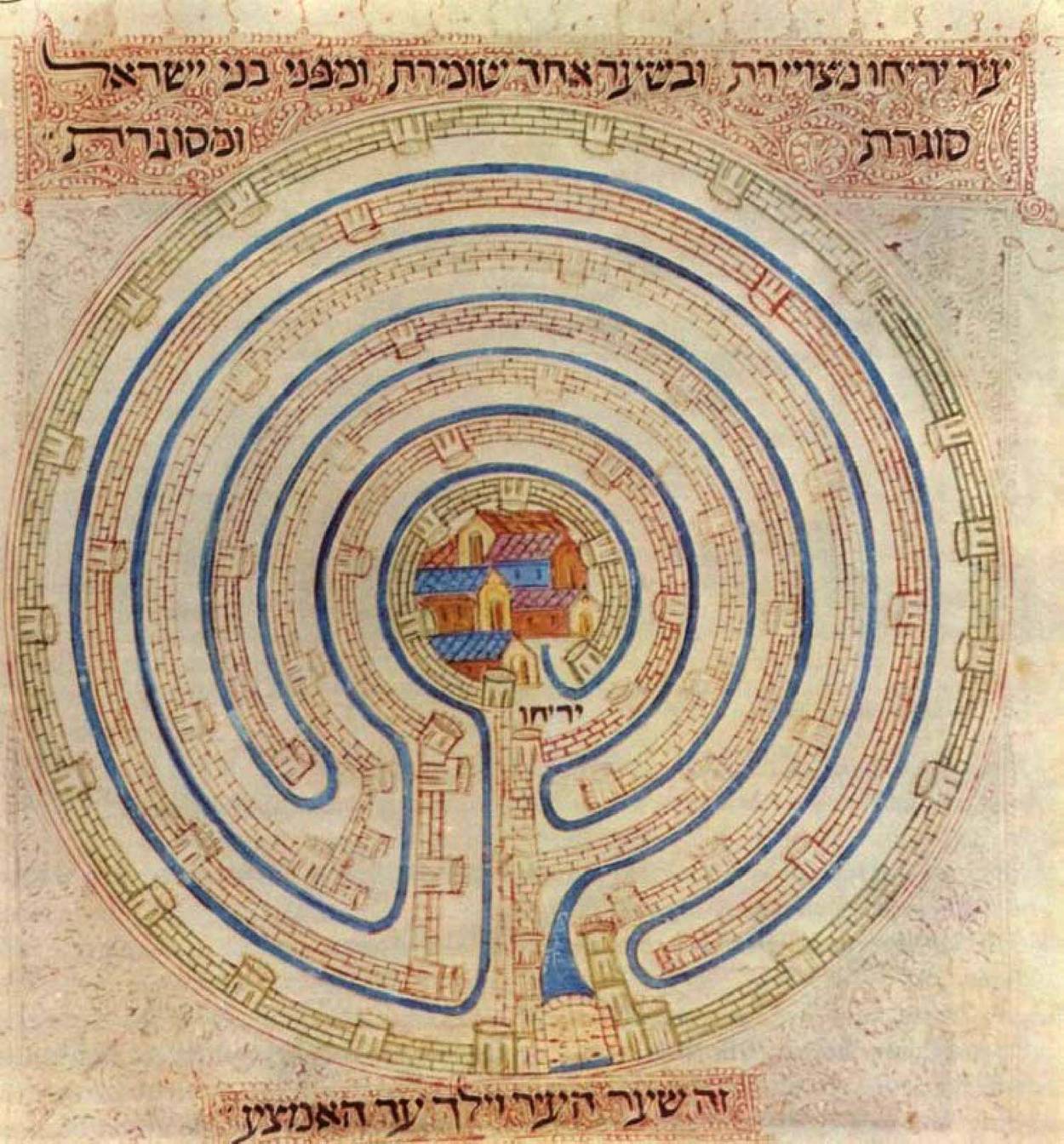

It was Rav who came up with the idea of the labyrinth. The house, he proposed, should be built in the form of a maze, so complex in its construction that neither God nor humans would be able to navigate it confidently. God would be situated at the center and humans on the periphery; they would attempt to find one another but would rarely succeed. Furthermore, said Rav, the walls of the labyrinth should be made as attractive as possible, to discourage attempts at solving the puzzle at all. Some sections would contain long stories and fantastical artwork; other stretches would be utterly blank, so large and open that a person might spend their entire life writing in them without ever seeking the center. To make the labyrinth attractive for God, the center of the maze was covered in pictures of humans and stories of the Temple days; they were not quite food, but they were close enough.

But a labyrinth of this magnitude could not be built overnight; it was the work of generations. The rabbis set to work, knowing they were pursuing a task that they could not complete, whose fruits would be unavailable even to their grandchildren. They built their lives around the labyrinth: building, playing, sleeping in tents, singing, expanding it day after day until the final day, far in the future, that it would finally reach critical mass. The rabbis worked with a single mind, never getting mired in arguments, as though they knew each other’s thoughts, aware of the audacity of a project that dared to touch heaven.

The labyrinth took 300 years to complete. When it was finally ready, Rav Ashi tied a long string to the door of the study hall and, when he was at a safe distance, pulled the door open. It was the middle of the night; a bright cloud of smoke exited the hall, hovered for a moment, and then, with the force of a tornado, dove directly into the center of the labyrinth. Ravina, his friend, hiding behind a rock, moved like lightning and covered it, blocking out the sun and sky. He placed the labyrinth in a bag.

They looked at one another: Had it worked? The sky was clear and cold; the galaxy spilled overhead, and it was quiet. Finally, Ravina closed his eyes, exhaled, and smiled. Together, they walked hand in hand, speaking of how they would rededicate the long-abandoned study hall.

David Zvi Kalman is a Fellow in Residence at the Shalom Hartman Institute and the founder of an independent Jewish publishing house.