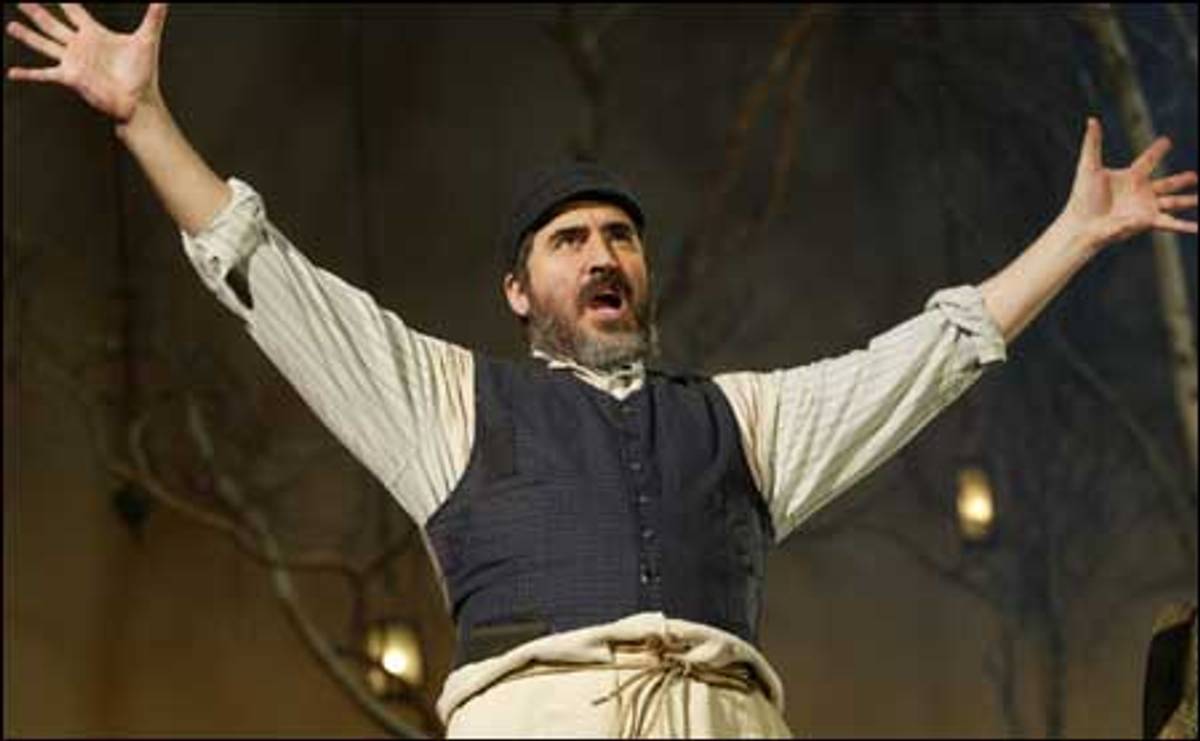

Ten days before Fiddler on the Roof reopened on Broadway with Alfred Molina as Tevye, Thane Rosenbaum declared in the Los Angeles Times that the revival “isn’t entirely kosher,” and mourned its “absence of Jewish soul.” Then Page Six quoted another complaint about the “ethnically cleansed version of the classic show,” setting the scene for an opening-night party where Post reporter Michael Riedel ended up on the floor of Angus McIndoe after arguing with director David Leveaux.

By then, the terms of debate were already set. “You wouldn’t expect actresses named Sally Murphy, Laura Michelle Kelly, and Tricia Paoluccio to abound in Russian-Jewish authenticity,” Jeremy McCarter wrote in the New York Sun. Other critics euphemistically noted the “Spanish-Italian” heritage of Molina—a London-born character actor versatile enough to play Levin in Anna Karenina, Diego Rivera in Frida, and Snidely Whiplash in Dudley Do-Right—as if it meant he was incapable of mustering enough Yiddish affect. “Being a goy myself, I won’t try to assess the Jewish authenticity of this Fiddler,” The New York Times‘ Ben Brantley said before consigning the production to Branson, Missouri.

Even some reviewers open to a production “more Chekhovian than Chagall” felt a need to defend Leveaux’s right to realize his vision. The New York Observer‘s John Heilpern parried the authenticity question by asking Rosenbaum, “what kind of name is Thane for a nice Jewish boy?” (As a precaution, Heilpern trotted out his Grandpa Motl, who wore spats to synagogue and probably wouldn’t have liked Fiddler much either.) “Accusations that the show has been goyified are baseless,” John Simon of New York, who has shown an acute (and sometimes disquieting) attention to actors’ ethnic traits over the years, wrote in praising the show’s “ecumenical” approach.

Most critics would not object to a Jewish actor doing Strindberg or The Sopranos; an Asian-American production of William Finn’s Falsettoland, a musical complete with a bar mitzvah, didn’t cause a fuss either. Having seen the show after sifting through the reviews, I can’t quite understand what all the fuss was about. Molina offers an unusually resigned and restrained Tevye, and except for John Cariani, who turns in a splendid, tightly wound Motel, the actors could all summon more spark, but the music, costumes, and choreography root the production in its traditional milieu. And while going easy on the schmaltz means the humor can fall flat and the evening drag, less exuberance also means less distraction from what is essentially a tragedy: a pogrom just before intermission disrupts Tzeitel’s wedding, Hodel joins her revolutionary love in his Siberian exile, and Chava’s marriage to a Russian can’t protect her family from the Tsar’s order to uproot them from the only refuge they know in a world that makes no space for Jews.

Peter Marks of the Washington Post, whose critique of the ensemble’s pronunciation of mazel tov places him firmly in the chorus of authenticity-seekers, suggests a deeper reason for their fierce disapproval. “In the secular Jewish home of my childhood, about the closest we ever came to spiritual sustenance was Fiddler on the Roof,” he writes. The original cast album was in heavy rotation on the Marks family hi-fi; his father sang “If I Were a Rich Man” in the car; his brother played Tevye at summer camp. “Anyone expecting an experience that reenergizes a connection stretching back four decades will be sorely disappointed,” he says.

For Marks, I suspect, and for his contemporaries weaned on Fiddler, the real problem with this production is not its thin Yiddish flavor, but its failure as ritual, its inability to trigger warm memories of childhood. It’s as if he’s returned to his old bedroom, found a new blanket on the bed, and decided that the mattress isn’t as cozy as it once was. The problem is, it will never be as comfortable as the one you remember.

Marks’ lament for the lost world of 1964 is an ironic echo (it’s unclear how intentional) of the ones that have dogged Fiddler, adapted from Sholem Aleichem’s Tevye the Dairyman stories, since its debut. While the ancestry of the creative team—Jerry Bock, Sheldon Harnick, and Joseph Stein—exempted them from comments like those made about Leveaux and Molina, some viewers found the original performances so broad as to be bothersome, and Robert Brustein thought their collaboration exerted “its wide appeal by falsifying the world of Sholom Aleichem, not to mention the character of the East European Jew.”

Brustein, Irving Howe, and Cynthia Ozick—for whom the fiction of Sholem Aleichem is the cultural madeleine that Fiddler is for Broadway reviewers today—have argued that even if Tevye’s richly textured Yiddish monologues, unfolding in a long-established culture threatened by persecution, assimilation, and emigration, could have been translated into the idiom of the postwar musical theater, the work of Sholem Aleichem was all but incomprehensible to an American-born audience. Never mind that the creators of Fiddler knew how much distance they had to bridge: “In working on the play, I found that what might be amusing to his audience would be bewildering to ours; what was moving in Yiddish could be over-sentimental, even melodramatic,” Stein wrote when the script was published. Howe held up Fiddler as evidence of “the spiritual anemia of Broadway and of the middle-class Jewish world which by now seems firmly linked to Broadway.”

Today, most children of that middle-class world Howe spoke of with such contempt know the lyrics to “Sunrise, Sunset” better than any prayer except, maybe, the Shema. This has been a casual learning process, not a conscious one, with endless reprises in student auditoriums, catering halls, and family rooms. Fiddler belongs to the shared pool of cultural knowledge that people quote from today, just as Sholem Aleichem’s contemporaries regularly cited Hebrew phrases that were familiar in a society intimate with scripture. Yet Jews who have felt that deficiency of spirit have found their way from Fiddler to Howe’s World of Our Fathers, the Tevye tales in translation, and even to daily services.

In 1999, while researching A Life in Pieces, I met a Polish woman, a lifelong Catholic, who met her biological sister at a conference of child Holocaust survivors in Prague. Only when she learned that her birth parents were Jewish, she told me, did she understand why her daughter’s favorite movie was Fiddler on the Roof. Hers was the logic of sentiment, of course, not evidence of the improbable persistence of her severed heritage, but it did open my eyes to the musical’s international appeal. As historian Stephen J. Whitfield has written, Fiddler was mounted two dozen times in the former East Germany in the five years after the Berlin Wall came down, and it became Japan’s longest-running musical. “It’s so Japanese!” one producer told Stein. “Tell me, do they understand this show in America?” And how: its eight-year run made it the longest sustained show on Broadway until Grease eclipsed it. This would have been impossible without a diverse sixties audience attracted to its universal themes of love, faith, and family in a period when children lost respect for their parents and the old order was crumbling.

These themes are Jewish themes, too, but the show’s Yiddish textual, musical, visual, and geographical setting make Fiddler a popular touchstone of what it means, or once meant, to look, sound, and act Jewish. (Today, alternative models abound; on Sex in the City, Charlotte York becomes a Goldenblatt, then adopts a baby girl from a Chinese Anatevka.) Still, people struggle to differentiate between outward manifestations and what it means to be Jewish. Part of Swiss clarinetist Bruno Doessekker’s transformation into Holocaust survivor Binjamin Wilkomirski was getting his hair curled and putting on a Yiddish-inflected German. I’ve also watched a real cousin develop a slouch over the past few years as he became a ba’al teshuva. Some of what he does—recite prayers, lay tefillin—requires acting and sounding differently than he once did, but his bold Boston accent has receded in favor of an Ashkenazic lilt he picked up from teachers or friends at yeshiva. Such performances should not be necessary to convince others—or oneself—of who you are.