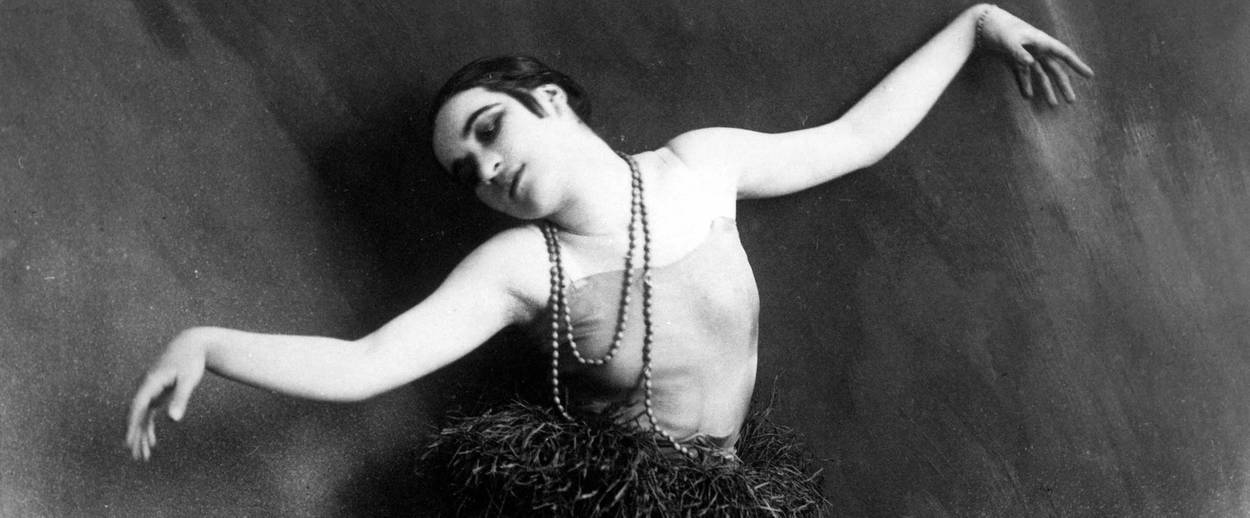

The Forgotten World of the Badass Valeska Gert

On her 126th birthday, measuring the influence of the incomparable ‘dance performance artist’ who inspired entertainers from German Expressionism through to 1980s punk

Valeska Gert is dying. On top of a brightly lit platform, she stands motionless in a long black dress. Slowly, she stretches, struggling, hands becoming fists, shoulders hunching, face twisting, the appearance of pain coursing through her body. She tries to scream but fails, a soundless ache ripping from her mouth. She tries to protect herself but life finds its way out of her shoulders, arms, hands. Suddenly there’s a hint of a smile, a glimmer of hope, but it disappears as quickly as it came. Her face weakens, her head collapses onto her neck, and soon she’s gone.

The audience doesn’t know what to do. They’ve just seen the German-born Gert perform her piece Der Tod, which in her native tongue means The Death. It was one of her many dance-portrait-pantomimes in which she took either an abstract concept or a character and brought it to life as a short burst of performance, sometimes even seconds long, for cabaret audiences in Weimar Germany, London, Paris, and other locations across Europe in the 1920s and early ’30s.

Today Valeska Gert tends to be identified as a “dance performance artist” because she used her body to tell socially critical stories in what seemed like bizarre or grotesque ways, and was perhaps the first modern dancer to do so. Yet Gert had roots in both dance and theater. In one of her (four) autobiographies, Ich bin eine Hexe (I Am a Witch, 1968), she describes her relationship to the two media: “I performed theater, I longed for the dance; I danced, I longed for the theater. I was in conflict until the idea occurred to me to combine them: I wanted to dance human characters.”

When Gert first began performing in Europe, audiences had no idea what to call her. She was a “dancer,” or “grotesque dancer,” or “dance-mime” or “dance-pantomime artist.” Audiences’ inability to categorize her became one her greatest strengths. There’s a famous drawing of her in which she coyly curtsies in pantaloons and stockings surrounded by 17 heads of audience members, each with a different expression—disgust, lust, bafflement, appreciation, curiosity, etc.—but the house is, of course, a packed one. Everyone came because they wanted to see her unusual performances for themselves.

Today, Gert might be known in dance circles, but to popular American culture, she is generally on the fringiest of the fringe. A Jewish woman, she was exiled from Germany in the 1930s as the Nazis came to power, and after that struggled to regain a foothold in the cabaret cultures that first brought her to fame. She would eventually be able to share her work again, but it would take decades in fits and starts until she would become cemented in the modern cultures of dance and theater.

***

Valeska Gert was born Gertrud Valesca Samosch in Berlin on Jan. 11, 1892 to upper-middle-class Jewish parents. She began ballet classes at 7, but never really had much interest in academics at school and dropped out. Beginning as a young girl and throughout her life, she showed not just an underlying distaste for cultural norms but a strong resistance to them.

By the time she was 23, she was studying acting, character development, and movement with Maria Moissi—work that would later translate into solo performances. Noticing her talents in these realms, Moissi referred Gert to dancer Rita Sacchetto.

Sachetto, a dancer beloved for her elegant ballets inspired by paintings, hired Gert for a performance in Berlin expecting something of similar taste from the young dancer. As Gert wrote in another of her autobiographies, Mein Weg (My Way, 1931), she had something else in mind:

I made myself a costume out of orange silk. … Full of bravado, I exploded like a bomb from the wings. And the same movements I’d danced soft and gracefully at the rehearsal I now exaggerated wildly. With giant steps I stormed straight across the podium, my arms swinging like a big pendulum, hands outspread, face contorted in a brazen grimace. … The dance was a spark in a powder keg. The audience exploded, yelled, whistled, hurrahed. I exited with a brash grin.

This 1916 performance, her Tanz in Orange (Dance in Orange), became her stage debut. It was the visual opposite of one of the biggest dance developments of the time, Ausdruckstanz, or expressionist dance. Ausdruckstanz was the beginning of German modern dance, a freer style of movement than ballet or folk dance that explored expressive spiritual realities via masses of bodies in movement choirs. Gert hated it, finding it bourgeois, boring, and rooted in a false sense of community.

‘I danced all of the people that the upright citizen despised: whores, pimps, depraved souls—the ones who slipped through the cracks’

Despite the popularity of Ausdruckstanz, Gert’s own, quirky Tanz in Orange began opening up doors for her, like the one at director Otto Falckenberg’s Munich Studio Theatre. Falckenberg cast her in a series of character roles and she became familiar with the work of the anti-realist, socially critical expressionists, who would also greatly influence her solo work.

According to author Sydney Jane Norton’s article “Dancing Out of Bounds: Valeska Gert in Berlin and New York,” it was at Falckenberg’s theater that “Gert perfected her ability to impersonate characters, capture a given movement or facial expression with acuity, and then magnify it to monumental proportions.” By the mid-1920s, Gert had a style all her own. Seeking to critique and parody social constructs, including Ausdruckstanz, she selected cultural ideas and stereotypes and blew up their traditional movements, much as she initially blew up the stage with the parodic Tanz in Orange. Nothing in Gert’s cultural vocabulary was sacred, from circus performers to boxers to tango dancers to Charleston dancers to love and birth and the aforementioned death. Her arms flailed, her eyes rolled, she thrust her hips, she bent and twisted and exaggerated her body’s shapes to unveil their stereotypes and critique audiences’ perceptions of them. As Norton writes, “Her incorporation of mass culture into her repertoire, together with her grotesque renderings of modern urban problems and bourgeois moral hypocrisies, place her performance art within in a late modernist, avant-garde genre, which served to expose and dismantle the ideological underpinnings of what many perceived to be an unacceptable social order.” Each piece was a seconds-long micro-caricature that both drew her audience in and alienated them at the same time.

Gert’s use of alienation is interesting because she did it at the same time as the person most famous for using it in his work, playwright and director Bertolt Brecht. Around the time Gert was performing, Brecht was developing his “epic theater,” a new form of presenting drama in which no attempts at illusion were made in order to promote social change. When Gert and Brecht met and she asked what epic theater was, he simply said, “It’s what you do.” She is considered, Norton says, to be “the first dancer who supplied German modern dance with a revolutionary aesthetic that catapulted the art form into the realm of critical thought and social consciousness.”

For her character performances, Gert chose subjects on the fringes, those regularly ignored by society. As she writes in Mein Weg, “Because I despised the burgher, I danced all of the people that the upright citizen despised: whores, pimps, depraved souls—the ones who slipped through the cracks.” One of her most famous performances was a series called Canaille, in which she performed a prostitute pre-, during, and post-assignation. A rebel in her time, she is possibly the first person who performed coitus onstage—as an orgasm performance that once resulted in police being summoned—as well as the first person to experiment with and critique gender onstage. Gert became an underground sensation in the cabaret and arts communities of 1920s Berlin, perhaps most comparable to the level of celebrity Laurie Anderson held in 1970s and ’80s New York. Through her work, Gert became associated with every avant-garde movement of her day, as well as Dadaism and surrealism, respected and hailed for her toughness, wit, fearlessness, and incisiveness.

Gert began performing all over Europe, at Brecht’s cabaret The Red Revue, in Paris, in London, and elsewhere. She also moved her parody into a new medium, performing in film alongside a very young Greta Garbo in the 1925 film Joyless Street; in G.W. Pabst’s 1929 film Diary of a Lost Girl also starring American cinema sensation Louise Brooks; in the first film version of Brecht’s The Threepenny Opera as Mrs. Peachum in 1931, and many others. Gert knew how to manipulate her face and her body to dominate a stage in her solo performances, and the same happens even when she’s on screen with multiple people, as in this scene from Diary of a Lost Girl:

Her face twists, her eyes expand, her mouth bends and even if she’s not saying anything, you simply can’t look away.

***

As the Nazis rose to power, the Jewish-dominated cabarets began to close and it became difficult for Gert to get work. Critics started to approach her work antagonistically instead of with the praise that had previously been lavished upon it; suddenly she was unpatriotic, unnatural, un-German. Nazi Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels even singled her out in his book The Eternal Jew, noting that her “bubbling jokes and an eye for the foibles of the times” were degenerate.

Gert made her way to London, leaving her beloved Germany as an exile. As war raged on in her adopted home, Gert then departed for the United States in 1939 to try her hand at first New York then Hollywood. No sooner had she arrived in California as a guest of prominent director Ernst Lubitsch, however, she referred to the actors there as “picture postcards and not humans!” and he refused to cast her. But she was barely able to get work with anyone else because she didn’t look like the “picture postcards” she disparaged.

Gert returned to New York and performed a few shows, but ultimately wound up for a short time penniless, unable to get even the most menial jobs. As a German immigrant, she was confusing to Americans who didn’t understand her satire; and she was discriminated against by other German immigrants because of both her Judaism and the socio-critical nature of her work.

Eventually, though, Gert was able to cobble together enough funds in 1941 to open her own cabaret in the West Village. Located at 3 Morton St., the basement space was called Beggar Bar. Many people who worked at Beggar Bar also performed there, like Judith Malina, who would go on to co-found New York’s incendiary Living Theatre; and a pre-fame Tennessee Williams, whom Gert later fired for refusing to pool his tips. With her new space, Gert now had a place to perform again and to promote the work of other experimental artists and exiled Germans. Shortly, Beggar Bar became wildly popular among artists, celebrities, writers, and entertainers. It even rivaled Café Society, the other major artistic nightspot in the West Village known for its promotion of now-legendary performers like Miles Davis and Billie Holiday.

But American involvement in WWII loomed, and with the changing American relationship to Germans so changed the success of Beggar Bar: It closed in 1945. Gert then tried to run another cabaret in Provincetown, Massachusetts, but to no avail. After the war, she moved back to Europe and opened other cabarets. She still worked wherever she could and never really stopped performing, even if people didn’t listen as much as they had in the past.

In the 1960s, though, film director Federico Fellini rediscovered Gert and cast her in his film Juliet of the Spirits. She then began to work more consistently in the public eye. In the 1970s, she appeared on a popular German talk show and her culture’s interest was revived in this quirky, sassy, funny woman with dyed black hair, chalk-white foundation, blackened eyebrows, bright blue eyeshadow, and red lips who, by her own account, had been totally forgotten. After the show aired, she was approached by high profile directors like Rainer Werner Fassbender and Volker Schlöndorff to work on new projects. Schlöndorff’s project was actually a documentary about her life, Nur zum Spass—nur zum Spiel (Only for Fun—Only for Laughs), released in 1977, which continued interest in Gert’s scandalous, rebellious life.

Interestingly, Gert’s appearance on this talk show also inspired Germany’s punk movement. Gert was a woman who crafted her image however she wanted and, according to Weimar culture specialist and University of California-Berkeley Professor Mel Gordon, on the show, Gert “had this punk-like notion that she was beyond the immediate responses of the audience. … She totally appealed to young people who had never heard of her.” Simply by looking at her, one can also see how she influenced the appearance of new wave/kraut rock performer Klaus Nomi and punk/new wave singer Nina Hagen, the latter of whom once called Gert a great role model. When Gert died at 86 in 1978, she had letters from young punks in her mail asking to meet her. As writer Gavin Blackburn said in a 2010 article on Gert, “Her acceptance, at the age of 86, by the burgeoning punk movement is as much a testament to her brash, no-nonsense energy as it is to her artistic achievements.”

Gert’s memory also lives on in the work she inspired, from Malina’s Living Theatre, which was greatly influenced by Gert’s performance philosophies, to that of German choreographer Pina Bausch and her pedestrian, grotesque movements, and the variety in modern dance as a whole. Last year, in New York, the New York Jewish Film Festival featured Gert’s work in time for her 125th birthday, and the Jewish Museum featured video of a Gert performance in its 2016 exhibition “Unorthodox” about nonconformist artists.

Valeska Gert’s influence is everywhere there is an artistic critique of society, everywhere an artist challenges a person to think beyond the bounds of what they know. People who have been inspired by Gert recognize the impact of her work not just in the Weimar era but today, which is really what she always wanted. “If an artist penetrates deeply into his time he will uncover its underlying significance and he will also create something that is eternal and universal for all mankind,” Gert said in a talk on Radio Leipzig in the 1930s. “Our works … will appear timeless to future generations only if they are profound enough. They will deliver a message which passes from generation to generation and which reveals that we are all human, we all have to follow the same laws, we all have to fight, we all have to die.”

Elyssa Goodman is a writer and photographer whose work has appeared in Vogue, VICE, Elle, and T: The New York Times Style Magazine, among many others