Fredy Hirsch’s Lover

Could a homosexual love survive Theresienstadt?

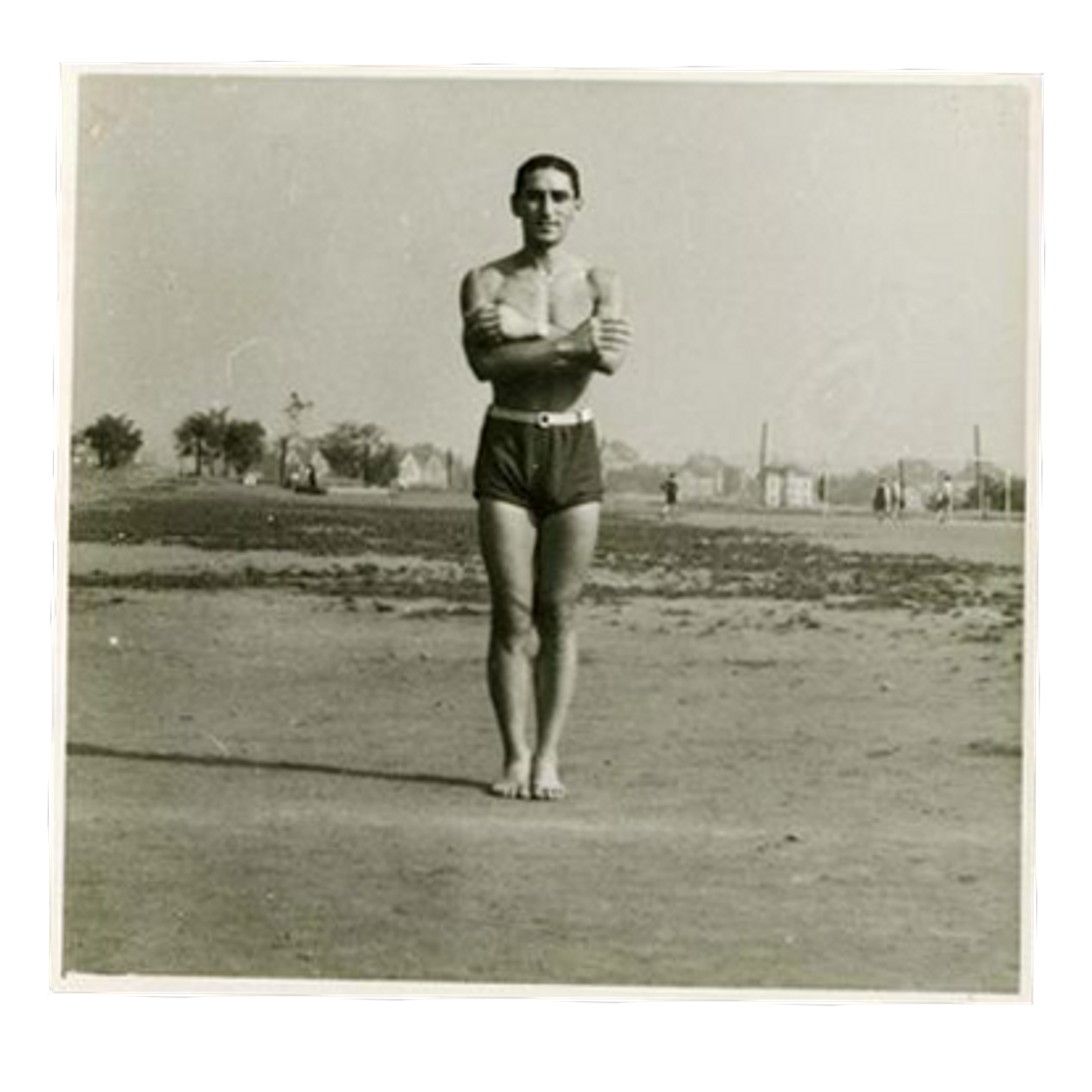

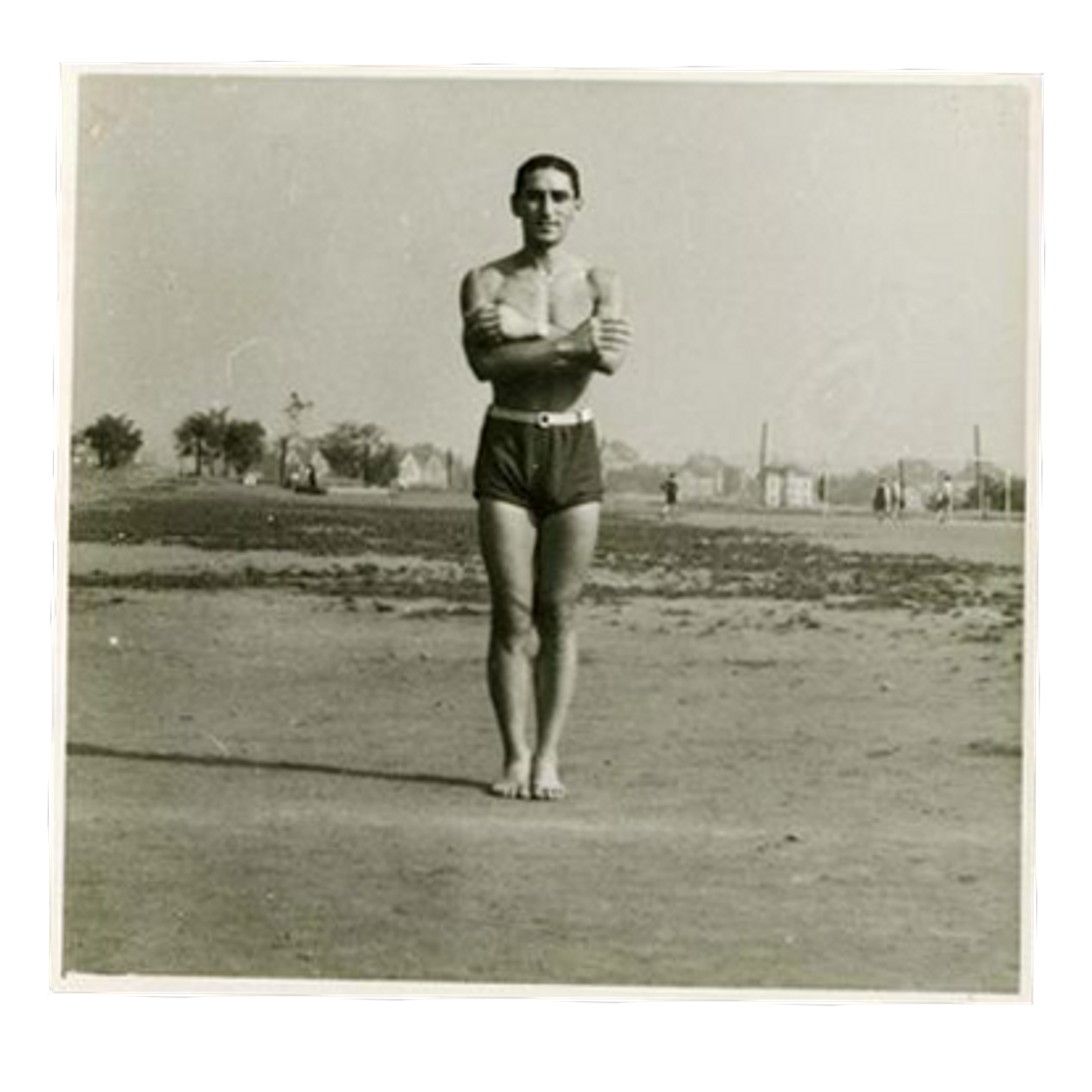

The LGBTQ history of the Holocaust remains uncharted territory. One of the very few known stories, painstakingly pieced together, is that of Fredy Hirsch. He was young, charismatic, good looking, and gay. Born in 1916 in Aachen, Germany, Hirsch emigrated to Czechoslovakia at age 19. A sportsman, he became a much-loved Zionist youth leader in the Theresienstadt ghetto and, later, in Auschwitz.

Prisoners in Theresienstadt knew Hirsch was gay. Two recent biographical documentaries, Heaven in Auschwitz by Aaron and Esther Cohen, and Dear Fredy by Rubi Gat, as well as Dirk Kämper’s book, address his homosexuality. But, until recently, we knew nothing about his private life. New research by myself and Alena Mikovcová into the Maccabi Brno association and interviews with eyewitnesses reveal that Hirsch’s partner of many years was a medical student named Jan Mautner.

The history of this couple is not only one of the very few queer love stories during the Holocaust that we are able to reconstruct. It illustrates how precarious any presumed interwar tolerance was.

Hirsch met his boyfriend in Brno, Czechoslovakia, in 1936; the two men both taught sports for Maccabi Brno, a Zionist sports association. Jan, also known as Jenda, was born in 1914, grew up in Olomouc, studied law in Prague and then medicine in Brno. The couple published articles together in the Maccabi journal, and Mautner translated Hirsch’s writings from German into Czech. Hirsch struggled with the difficult Czech language throughout his life.

In an interview, Ruth Kopečková, born in 1923 in Brno, survivor of Theresienstadt, Raasiku, Stutthof, and Neuengamme camps, told me that Mautner and Hirsch were a well-known couple in her hometown. For two years, Hirsch and Mautner organized winter trips for Jewish young people, during which Mautner’s mother cooked wonderful meals for the hungry teenagers.

In interwar Czechoslovakia, as in many countries at the time, both male and female homosexuality was punishable by law. At the same time, there was a lively activist movement pushing for decriminalization. Brno was in fact a key site of queer history: In 1932 the World League for Sexual Reform, led by the famous German Jewish sexual reformer Magnus Hirschfeld, convened there. Hirsch and Mautner lived together, and we can therefore assume that they had the blessings of Mautner’s parents.

Hirsch was de facto orphaned: His father died and his mother left the children when they were teenagers. In March 1939, Hirsch moved to Prague, where he continued to work for the Maccabi organization. Mautner, who was unable to complete his degree after the Germans closed Czech universities in 1939 following a student protest, followed his boyfriend in April 1940. That was an unusual decision for a single young man then: During the persecution, Jewish parents and their adult children usually lived together and faced deportation as a family unit. Mautner’s parents remained in Brno. The two men taught together sports at the Jewish center Hagibor (”The Hero”). In the final years before the deportations began, Hagibor offered the only recreational activities for Jewish youth in Prague.

In November 1941, Hirsch was deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto. Together with Gonda Redlich, the 25-year-old Zionist activist, he became the head of the ghetto’s Youth Care department, led sports education, and attempted to instill hope and self-respect in children and teenagers, whose experience growing up had often been marked by denigration and insults. This remarkably good care was made possible due to the fact that the Jewish self-administration of Theresienstadt dedicated significant resources and manpower to caring for children in the ghetto.

Redlich took care of organizational tasks while Hirsch was more in the forefront of child care. He visited the newly arrived transports who waited to be processed in the ghetto and made sure that there were caretakers to provide activities for the new children prisoners. Hirsch also set up regular sports activities, morning gymnastics in the outside as well as soccer games. He also insisted on strict hygiene, that children washed and kept their mass accommodations orderly.

Hirsch’s strict discipline sometimes irritated the youngsters and they poked fun at him, but he managed to establish a routine for the children and in insisting on cleanliness, contributed to keeping illnesses in the dirty surroundings at bay. Hirsch led by example, managing to stay clean, well dressed and with polished shoes, cutting a good figure.

***

None of the legendary stories about Fredy Hirsch in Theresienstadt, however, tell us anything about his love life.

Here is one of the conundrums of this sort of research. We know that, six months later, in July 1942, Mautner was also sent to Theresienstadt. Mautner’s parents had preceded him there; they were then deported to Zamość ghetto, where they were murdered soon after. But the trace ends here: We have no information about Mautner’s time in Theresienstadt; we do not know whether he and Hirsch were still a couple.

We do know that Hirsch remained in Theresienstadt for almost two years. In September 1943, he was deported to Auschwitz with 5,000 men, women, and children to what became known as the Family Camp. Even in Auschwitz, during the last six months of his life, Hirsch managed to set up a children’s block, attempting to shelter the youngsters from the horrible brutalities of camp life. On March 8, 1944, Hirsch and the remaining members of his transport were all murdered.

Why did we not know about Hirsch’s partner? It is quite possible that Hirsch’s great love disappeared from general memory due to the homophobia of the prisoner society. This prejudice continued in survivors’ testimonies and in fact colors Holocaust history to this day.

One particularly deep-rooted homophobic slur is presumed pedophilia of gays and lesbians. Hirsch was accused of being attracted to boys; some survivors remembered Hirsch groping them. T.F., who was 13 years old at that time, recalled that Hirsch tried to stick his hand into his trousers, and that F’s older brother beat Hirsch up. In Theresienstadt, youth care leaders were warned not to leave the boys alone with Hirsch during showers. It is a shame that none of the recent works on Hirsch address these accusation of pedophilia, as we do not know if the accusations are justified.

In December 1943, Jenda Mautner was deported to Auschwitz. In July 1944, he was selected for forced labor and sent to Schwarzheide, a satellite camp of Sachsenhausen, located in the Lusatia coal-mining region of Saxony, Germany. There the prisoners were forced to work in hydrogenation plants that transformed coal into high-octane aircraft fuel to aid German industry. Less than half the prisoners survived the grueling forced labor and the death marches at the end of the war. In April 1945, the SS chased the prisoners on foot back towards Theresienstadt.

Mautner was among those who made it out alive, though not unscathed. He emerged with severe tuberculosis and a decimated family; his parents and his sister were murdered. He later left the Jewish community and changed his surname to Martin.

Soon after the war, Mautner lived with the family of his cousin, who survived the war in Palestine. Mautner’s great-nephew, who is today over 80 years old and lives in Australia, is one of the last people to remember him. “Jan was flamboyant and very intelligent,” he recalled. “I tested his memory, with some astonishing results. He was apparently able to memorize a long list of words and repeat them both in the original order and in reverse order. Mautner said that he never had to study hard, he just read the material before an exam and that was sufficient.” When I asked about Mautner’s sexual orientation, it turned out that “flamboyant” was a code word for gay.

Mautner had a few happy years following the war. He passed his professional exams and was able to work as physician. He also found a new love, Walter Löwy, a pharmacist whom he met in Schwarzheide. Löwy and Mautner lived together in a Prague apartment next to the leafy Stromovka park. But in 1951, Jan died of tuberculosis. It is tragic that the physician who was the partner of one of the leading Jewish figures during the Holocaust succumbed to a disease that, at the time of his death, was treatable with antibiotics. Socialist Czechoslovakia had antibiotics, though only in limited quantity. Moreover, many patients could be successfully treated with traditional methods, such as mountain sanatoriums.

***

This already devastating story has a bitter afterlife. The only people who can recall Mautner and his relationship with Hirsch are Theresienstadt survivors. However, my request to the newsletter of the Czech Holocaust survivors’ association to publish a call for witnesses who might remember the couple turned out to be unexpectedly controversial. A survivor vetoed the request, claiming that the well-known public secret of Hirsch’s homosexuality ought not to be aired, “lest his memory be besmirched.”

After much debate, the newsletter permitted publication of a short piece, though it was heavily censored: The reader would not learn that Hirsch and Mautner were lovers, that they were gay, or why a historian would be interested in Mautner. It was dispiriting proof that even today, speaking of the homosexuality of a Holocaust victim is considered slanderous. I asked the vetoing survivor to grant me an interview to clarify why she believed that someone’s homosexuality was a priori insulting; the entire board of the survivor association refused to deal with me and chastised me for being “obstinate.”

The tragic irony is that it was the Czech survivors’ association that, through this decision, took the final step in erasing the last traces of a great queer love story in the depths of the Holocaust. We need to fight to save it.

***

An earlier version of this essay came out originally in Tagesspiegel.

Anna Hájková is associate professor of history at the University of Warwick. Her book The Last Ghetto: An Everyday History of Theresienstadt is forthcoming in 2020 with Oxford University Press. She is working on a book on the queer history of the Holocaust and would be grateful for any information on relevant family archives. Her Twitter feed is @ankahajkova.