Because I make it a habit not to see movies about Nazis or movies starring Tom Cruise, I missed last year’s Valkyrie, which sat

at the intersection of those two genres. But that is not the only reason why the film, which gave the big-screen hero treatment to Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg, made

me uneasy. Stauffenberg, who detonated the bomb that failed to kill Hitler on July 20, 1944, and paid for it with his life, undoubtedly possessed some of the key characteristics of a hero: he was brave and he was true to his principles. The problem is that tho

se principles, which inspired him and the other Catholic aristocrats who formed the heart of the conspiracy against Hitler, were neither liberal nor humanitarian.

Rather, the conspirators of Operation Valkyrie—the code name for the Army’s plan to unseat the Nazi Party and take over the German government—were motivated by a combination of religious piety, old-style German nationalism, and prid

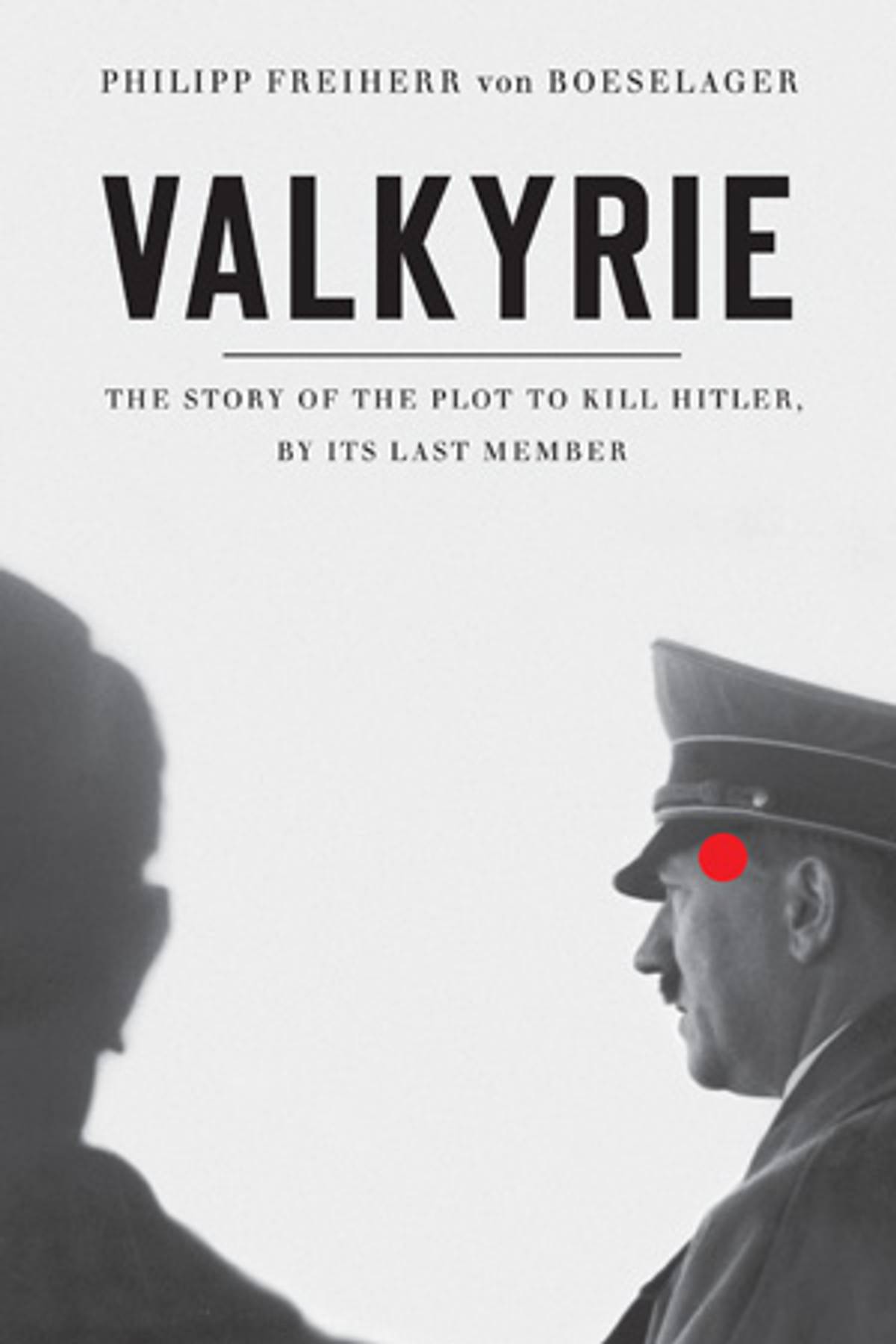

e of caste. That is the unmistakable lesson of Valkyrie: The Story of the Plot to Kill Hitler by Its Last Member, an important and troubling new memoir by Philipp von Boeselager, who managed to complete the book before his death last year at the age of 90.

Many readers will doubtless be drawn to the book after seeing the movie, in search of a first-hand account of the historical drama. They will be partly disappointed: von Boeselager was part of the same conspiracy that included Stauffenberg, but he never knew the assassin, and the events of July 20 make almost no appearance in the book. One has to look elsewhere for the details of the bombing, which took the lives of several people at a meeting at Hitler’s Wolf’s Lair headquarters but left the Führer with only minor injuries. It was a case of sheer bad luck: Stauffenberg left his briefcase-bomb under the conference table as planned, but someone kicked it away, and when it went off the table shielded Hitler from the blast.

But Valkyrie does offer a vivid account of von Boeselager’s part in the plot. First, he had to procure explosives for the bomb, which he was able to do because “as the regiment’s bomb expert, I…had no difficulty removing some from our stocks.” In the autumn of 1943, he writes, he flew to an army base near the Wolf’s Lair with twenty bricks of explosive in a suitcase, and handed them over to a fellow conspirator, General Helmut Stieff. He feared discovery the whole time, especially when a soldier noticed him struggling with the heavy suitcase and offered to help. Von Boeselager implies that it was his explosives that Stauffenberg detonated almost a year later, but in fact, as the book’s editors note, there were at least four different channels bringing bomb materials to Stauffenberg, and it’s impossible to say whether von Boeselager’s were used or not.

His second responsibility was much more crucial, though the failure of the assassination attempt meant that he was never to carry it out. On the evening of July 19, von Boeselager recalls, he led a detachment of 1,000 cavalrymen away from the Russian front, toward an airfield in occupied Poland. As he tells it, the plan was for the troops to be flown back to Berlin, where they would help secure the city in the chaos following Hitler’s death. The midnight ride was aborted when von Boeselager received a coded message, “Everyone to the old foxholes,” telling him that the plot had failed and the men should hurry back to the front. (The historian István Deák, writing about Valkyrie in The New Republic, has cast doubt on this and other elements in the book, arguing that it would have been impossible to commandeer enough airplanes to carry 1,000 men away from the fighting.)

That crucial message came from von Boeselager’s older brother, Georg, who was even more deeply involved in the Valkyrie plot. If he hadn’t been killed in combat shortly after July 20, he might well have been exposed and executed, and Philipp along with him. Philipp’s hero-worship of his brother still shines through these pages, more than 60 years later: he writes about Georg as a kind of chivalric knight, brave and true, as loyal to his men as he was defiant of his evil master. Indeed, there is a constant cognitive dissonance in von Boeselager’s descriptions of his older brother’s exploits. Each time the dashing Georg won a battle or captured a town, he was furthering Hitler’s goals and the Final Solution; yet Philipp cannot help idolizing his martial prowess. He brags that, during the invasion of Russia in 1941, Georg’s unit of 200 cavalrymen captured 700 prisoners, 175 horses, 60 horse-drawn vehicles, ten trucks, and a tank!” Knowing the probable fate of those prisoners in the German slave-labor camps, the reader may wish that he had at least omitted the exclamation point.

Yet this kind of moral ambiguity is at the very heart of Valkyrie, and of the Valkyrie conspiracy. Von Boeselager and his accomplices were sufficiently opposed to Hitler to try to kill him in July 1944—significantly, after the Normandy landings and the collapse of Germany’s Eastern front made it clear that Germany had lost the Second World War. But their convictions did not stop them from serving in the Wehrmacht, or from taking pride in Germany’s victories over France and Russia, or from abetting the genocide of Jews that took place wherever the German army held sway.

Of course, von Boeselager expresses the proper revulsion for Nazi war crimes. Indeed, one of the things that drove him into rebellion, he writes, was learning about the war crimes of Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski, the sadistic SS officer in charge of killing Jews and Gypsies in the central sector of the Russian front. Von Boeselager’s awakening came in the spring of 1942, when a memo from Bach-Zelewski happened to note “special treatment of five Gypsies.” When Field Marshal Kluge, the commander whom von Boeselager was serving as an aide, asked for an explanation, Bach-Zelewksi coldly replied, “All the Jews and Gypsies we pick up are liquidated—shot!” “I felt the kind of internal dislocation and devastation that leads to panic,” von Boeselager writes.

Yet it is highly improbable that such a well-connected officer, in the third year of the war, could have been ignorant of the mass murders that had been taking place since the very beginning. Indeed, von Boeselager hedges a bit when he writes, “Kluge could not have been unaware that crimes, major crimes, had been committed in areas under his authority. Still, we had attributed them to the uncontrolled excesses of the SS.” The only new revelation was that these “excesses” were actually state policy, “a doctrine of extermination”—a notion that no one who had paid attention to Nazi policy towards Jews since 1933 could have found entirely surprising.

But then, as von Boeselager writes, officers like him—cavalrymen with “von” in their names—were “hermetically sealed off from much of the outside world. Constructing a spirit of comradeship was more important for us than pretending to be citizens of the world. Sports were far more important than political discussions.” Indeed, one of the bizarre aspects of Valkyrie is how seriously von Boeselager and his fellow horsemen pursued field sports even as the war raged. He writes idyllically about hunting in occupied France: “Fate had been good to me: I was based south of Orleans, in the middle of Sologne, a hunter’s paradise…I still have very pleasant memories of those few months….” Even in 1945, after his unit surrendered to the British in Austria, they whiled away the time with “equestrian tournaments, Roman chariot races, and even [acting out] the rape of the Sabines in period costume.” One can’t help remembering that, at the same moment, hundreds of thousands of German women were being raped, for real, by Red Army troops.

What bothered von Boeselager most, what converted his passive dislike for the Nazis into active conspiracy, was not just Hitler’s evil. It was the realization that his beloved army, and its well-born officer class, was being tainted by that evil—that he was not as hermetically sealed off as he believed. “The Army, by remaining silent, was making itself the system’s accomplice,” he writes. That his outrage was a question of military pride, as much as morality, is clear enough from his description of Bach-Zelewski: “his service record did not inspire respect,” von Boeselager writes, not merely because he was a mass murderer, but because he had been expelled from the Army after World War I, and because he was an “unscrupulous careerist.”

While one may be troubled by von Boeselager’s reasons for turning against the Nazi state he served so well, there is no gainsaying the moral and physical courage he demonstrated in the plot against Hitler. It is no wonder that postwar Germany, desperately in need of some goodness to set against the vast cowardice and evil of the Nazi years, has made a cult of the Valkyrie conspirators. But it is a cult that the rest of the world ought to think twice before joining.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.