Fwr Vwls 4 Futr Englsh?

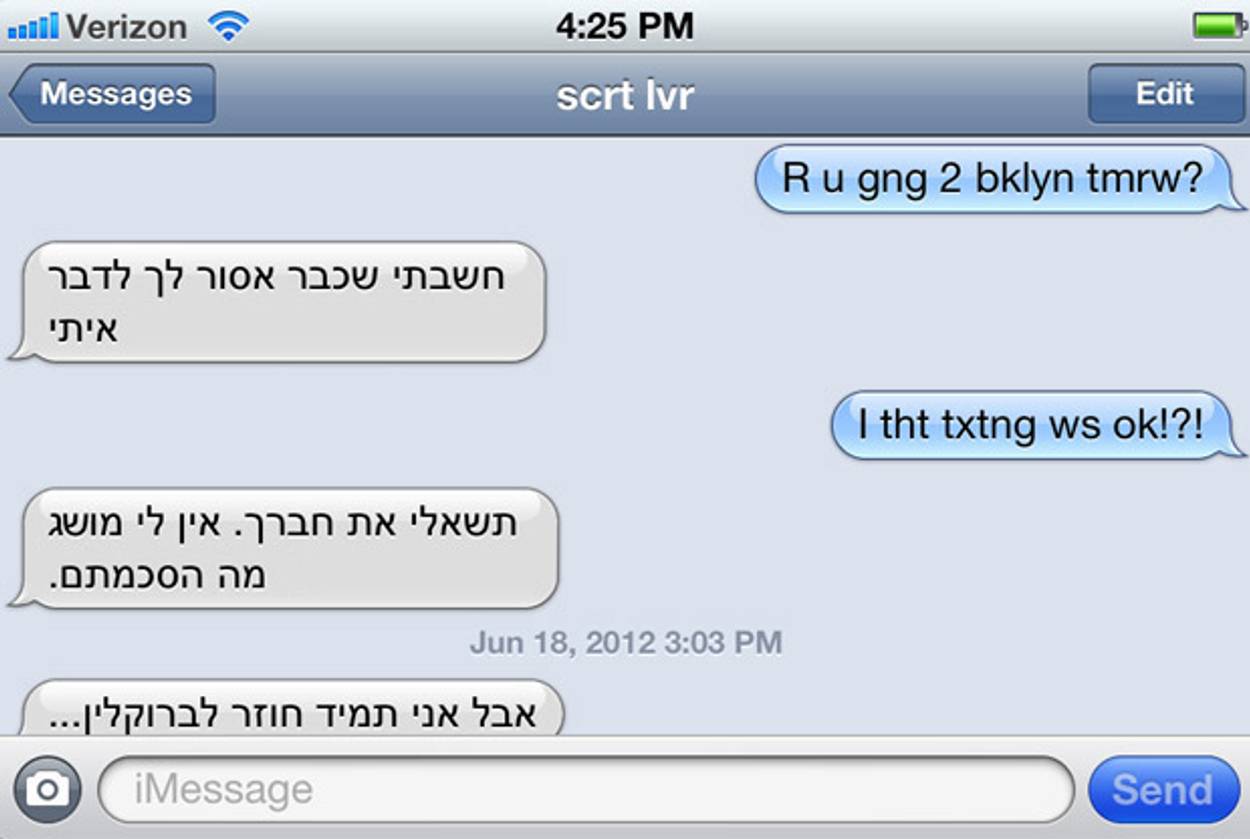

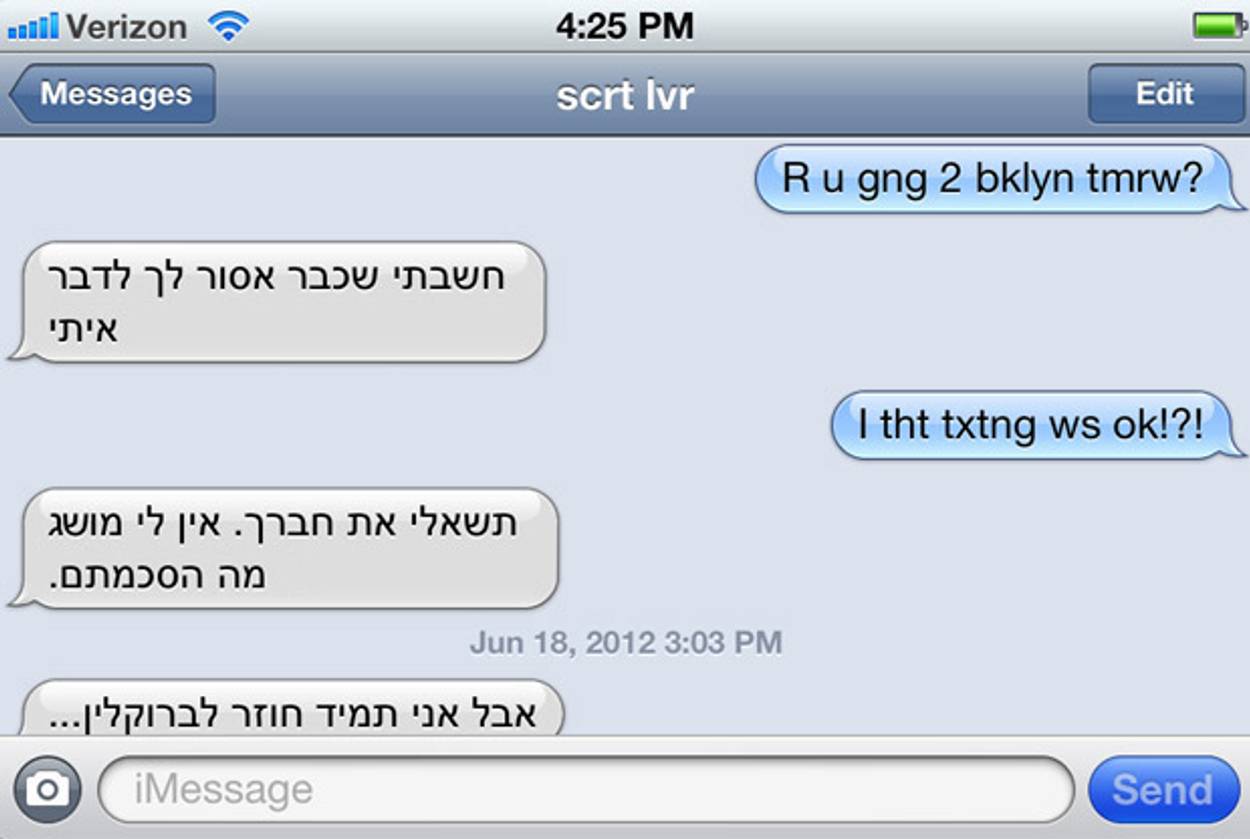

As Twitter and text messages force linguistic brevity, English starts to look more like vowel-free Hebrew

Might Twitter and text messaging push vowels out of English? Could the language end up looking more Semitic than Germanic?

I’m used to seeing abbreviations on Twitter, chat programs, and text messages on mobile phones. But I was surprised recently when an editor closed an email with “Rgds.” The “s” on the end helped me guess that it wasn’t short for “Rigid” or “Raged,” or so I hoped. Given the context, I assumed he meant “Regards.”

But I wondered how such a word ended up in a business letter. Did it mean that Twitter-ese is making its way into formal, written correspondence? “Rgds”—a string of consonants, vowels implied—reminded me a bit of Hebrew. While a dot system helps Israeli children learn vowels, the dots eventually come off, like training wheels, and adults read and write without them.

While text messages technically limit users to 160 or 320 characters, the average text message spans only 20 to 40 characters, according to Naomi Baron, a linguistics professor at American University and the author of Always On: Language in an Online and Mobile World. So, brevity isn’t forced upon us, it’s more a matter of “how much we want to type,” she said.

Abbreviations are a way “to show that you’re hip, you’re in the know, you’re cool,” Baron said. They’re not necessary. Nor are they new. They’ve been popular for at least a thousand years. “Because if you’re writing on parchment and you’re copying manuscripts [by hand],” Baron said, “you would like to save sheep hides and you’d like to save your efforts.” The advent of the printing press standardized some abbreviations. Still, people—out of either laziness or ingenuity, whichever you prefer—kept shortening words. As is the case today, vowels were often the thing to go.

Baron offered an example from the 18th century, when gentlemen closed written correspondence with “Yr hm srv,” short for “Your humble servant.”

In the 1930s and ’40s, Baron said, friends signed letters with “BFF”—short for best friends forever. I remember B.F.F. from my pre-teen days, in the late 1980s and early ’90s. It was everywhere: on the notes we passed in class; in the saccharine sentences we scribbled into each other’s notebooks; on the heart-shaped pendants that best friends wore. “We do tend to reinvent the wheel sometimes,” Baron said. “But, absolutely, [BFF] existed decades before this.” There’s of course no shortage of references to it now.

And, by the way, “btw” didn’t spring from chat, Twitter, or text message. Nor did “b/c” for because or “b/w” for between. All are, Baron said, “way old.”

According to Carmen Fought, a linguistics professor at Pitzer College and the author of Language and Ethnicity, there is a chance that such common abbreviations could make their way into spoken language. “The word ‘because’ becomes ‘bec’ because people are used to [using b/c],” Fought said, adding that students are saying “LOL” aloud, pronouncing the common acronym for “laugh out loud” like the word “loll.”

This phenomenon is common in the Philippines, where abbreviations are embraced (a little too enthusiastically, some say). For example, a Filipino who has grown up in America, or who has an American parent, is called a “Fil-am.” Overseas Filipino workers are referred to by their acronym: OFWs.

English is similarly open. Fought explained: “It’s like this mutt language, like the dog you pick up from the shelter that’s a little bit of this and that. We’ve got Latin roots, Greek roots, French, German, Scandinavian borrowings. English will borrow from any language.”

Because English is so chaotic, many English-speakers have a hard time learning to spell. And they seem to drift, naturally, toward what looks more like the Semitic system.

“What we do know about children learning to write English is that if they are allowed to spell however they wish,” Baron said, “they leave out the vowels. In English, figuring out which vowel to put is tough. The consonants are generally much easier to figure out.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Mya Guarnieri is a Jerusalem-based journalist and writer.

Mya Guarnieri is a Jerusalem-based journalist and writer.